Nurses of World War II: The Largest Group of Women in US History To Be Taken Prisoner of War

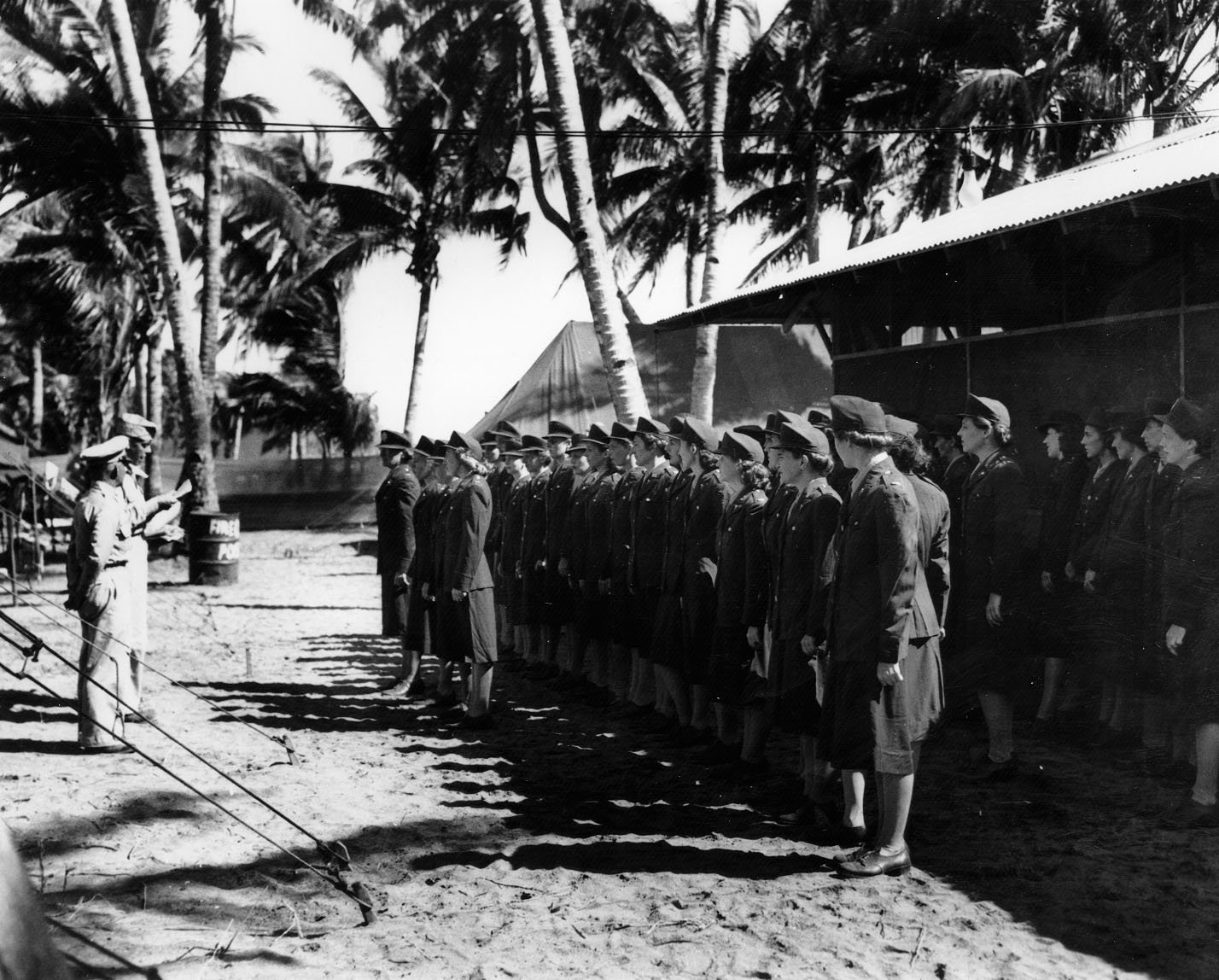

Japanese forces captured the nurses on Corregidor in 1942. The nurses, along with 3,700 men, women, and children civilian prisoners of war, were liberated from Santo Tomas Internment Camp in Manila, by the First Cavalry Divison on 3 February 1945. Brig. Gen. Denit, Chief Surgeon, Southwest Pacific Area, awarded the Bronze Star Medal and one grade promotion to the nurses, on the beach at Leyte. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The Philippines was the ideal destination for nurses seeking adventure in a tropical paradise. The warm weather, palm trees, and clear blue ocean departed from the usual setting found on military bases, hospitals, or aid stations back home. It was a cushy gig where most of their attention was occupied with golf outings, bowling over at the Army and Navy Club, fine dining, and falling in love.

Twelve hours after the Japanese surprised the United States at Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, warplanes filled the air over the Philippines just as the women from the US Army and US Navy were changing shifts.

Rumors ran wild and the sense of security and exotic wanderlust had disappeared. The nurses immediately sprang into action, including Josephine Nesbit from the Army Nurse Corps. She and other nurses fled from Sternberg Hospital in Manila to set up the Army Field Hospital No. 1 at Little Baguio in a jungle on the Bataan Peninsula.

The jungle environment was harsh. The nurses were exposed to dysentery, mosquitos, and malaria while they tended to traumatic injuries suffered by US servicemen. Gunshot wounds and blast injuries, the sick and dying, and the bandaged and bedridden — the “Angels of Bataan” nursed 6,000 patients back to health over the course of four months.

Lt. j.g. Ann Bernatitus, a US Navy nurse who transferred from Manila to the field hospital, became the first American of any branch in US military history to receive the Legion of Merit with Combat “V.” Bernatitus was exposed to numerous aerial bombing runs, one that even destroyed the field hospital she had worked in. In her dedication, she pushed through dysentery and beriberi, ignoring her own troubles to tend to others with more serious afflictions. She was one of the lucky ones, evading capture and chosen to evacuate on the USS Spearfish submarine to Australia.

Back in Manila, 11 Americans and one Filipina nurse assigned to the US Navy weren’t so lucky. They were captured by Japanese forces in the final days of January 1942. Their captors did not follow the rules of the Geneva Convention, so the nurses, corpsmen, dentists, and surgeons were placed in a civilian concentration camp run by the University of Santo Tomas. The former college campus was a far cry from its previous appearance — dormitories and classrooms now transformed to house 3,100 men, women, and children with meager supplies to go around.

Inside, their Japanese guards provided two meals of rice and vegetables a day, the grain infested with mold and the vegetables often spoiled. The POWs slept on slatted cots overrun with bed bugs. The nurses managed with what little medical supplies they had to aid their fellow prisoners. Every so often they received new arrivals, informing them of the latest developments on the islands. Morale only dwindled during their captivity.

In the months that followed, the Japanese military steamrolled through the Philippines. One by one the islands fell, and scores of Americans were death-marched to POW camps, including the “Battling Bastards of Bataan,” who walked 68 miles in 100-degree heat to their new home in Santo Tomas. They were greeted by 78 welcoming faces they knew as the “Angels of Bataan,” as well as 12 new faces from the Navy.

The mutual smiles and greetings were temporary, as the Japanese had built another POW camp 40 miles away in the countryside, at Los Baños, another former college campus. All 12 Navy nurses volunteered to leave because, if they hadn’t, the POWs would be left to survive on their own without medical treatment. As they were loaded onto trucks, the song Anchors Aweigh played over the loudspeaker, the final departure for the “Twelve Anchors” of the camp.

With their new nickname and spirit, the Twelve Anchors provided a lift in morale for others in the camp. The once-prevalent donations and incoming aid became almost nonexistent. Thus, the nurses used spare fabric as bandages and found flowers and herbs from a garden to craft medical potions. Their efforts could only save so many as the weakened inmates, suffering from malnutrition, begged for insulin or vitamins — medicine that wasn’t available.

The arrival of outsiders also came to an end after the Japanese issued an execution order on Jan. 25, 1944. Any American, whether civilian or military, caught by Japanese forces would be killed on sight.

On Feb. 23, 1945, 200 Japanese guards left their duty stations to conduct morning calisthenics around 7 a.m. The nurses and POWs, many of whom were down to skin and bones, heard gunshots and explosions outside. It was a rescue mission. US Army paratroopers descended on the Los Baños Internment Camp, killing several of the Japanese soldiers in a coordinated ambush. The remaining Japanese fled for their lives.

The evacuation wasn’t easy. Japanese reinforcements were alerted of the sudden attack, and Japanese planes and foot soldiers crashed the liberation. Navy nurse Margaret Nash cradled a baby who was just three days old in her arms and sprinted for the beach.

“Stray bullets were going in every direction,” Nash remembered of those moments on the beach before she scrambled aboard an amphibious boat. “I covered the baby,” named Elizabeth, “with a great big hat,” she explained, “and lay down on the sand over her.”

Three years in captivity — their war was now over.

The Angels of Bataan and Twelve Anchors walked into hellacious POW conditions in 1942 together, and all returned home safe in 1945. All the nurses were awarded Bronze Stars and Presidential Unit Citations for their heroism. They were the largest group of American women held hostage in American history and all believed a sense of humor keeps hope alive in even the most desperate circumstances on Earth.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.