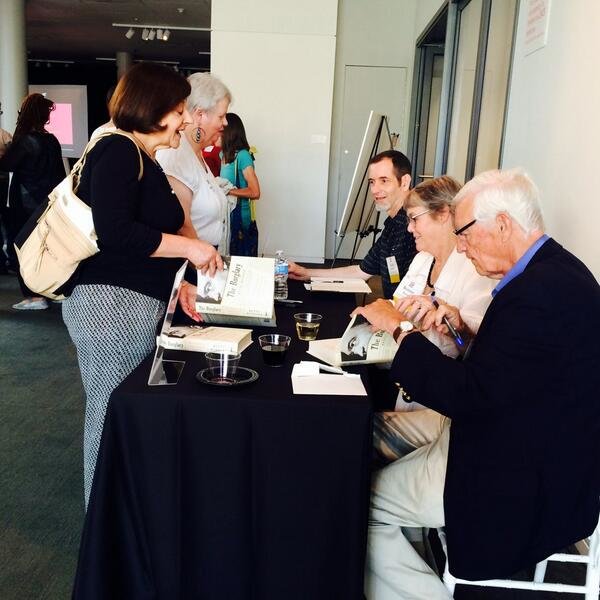

John and Bonnie Raines were parents of three young children when they decided they wanted to help burglarize the FBI in 1971. They were never caught by the authorities. Photo courtesy @LadyOfSardines via Twitter.

On March 8, 1971, boxers Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier faced off in a bout billed around the world as the “Fight of the Century.” The legendary fight, which took place at Madison Square Garden in downtown New York City, went a full 15 rounds, and both athletes landed devastating blows. The judges unanimously scored Frazier as the winner. It was Ali’s first loss as a pro boxer, one which he refused to admit publicly.

More than 300 million people watched the fight, including about half of the entire British population and millions more from as far away as South Korea. The fight had a significant impact on the civil rights movement. It also provided cover for a daring heist some 115 miles away in Media, Pennsylvania.

A small contingent of activists planned to burglarize a small satellite FBI office, searching for secret files proving investigative overreach. The burglars anticipated the much-hyped Ali-Frazier fight would distract security personnel.

The group of eight waited anxiously as personnel locked up the FBI office building for the night. But the plan hit a snag early on — a shiny new lock on the door. Among the burglars, Keith Forsyth was the designated lock picker. He quickly judged the new lock was unpickable. So the group would have to find a new way in, jeopardizing months of casing work. Forsyth was able to crowbar the side entrance open, and the group entered without resistance.

What the group found inside was beyond its boldest hopes — an empty office building with no guards, unlocked file cabinets, no alarms to trip, and a gold mine of confidential files to pilfer.

The activists hurriedly grabbed what they could — a trove of approximately 1,000 documents detailing grievous overreach by the FBI. And then they fled.

After the burglary’s statute of limitations expired decades later, seven of the original eight thieves came forward in 2014 to give their story to journalist Betty Medsger. In 1971, Medsger was a Washington Post reporter who received 14 of the stolen documents from the Pennsylvania burglary. Five of the seven burglars revealed their names for Medsger’s 2014 book, The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover’s Secret FBI.

At the time of the 1971 burglary, Bonnie Raines was a 29-year-old mother of three. She had previously disguised herself as a student conducting “research on opportunities for women” to get a look inside the FBI office in Media.

The burglars called themselves the “Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI,” and they went on to send copies of their stolen files to news agencies, journalists, and two senators. Medsger was the only journalist at The Washington Post to publish a story based on the stolen FBI files and the only journalist who did not return the files she had been sent when the FBI requested she do so.

Medsger’s subsequent stories revealed an FBI counterintelligence surveillance program called Cointelpro.

In response to the Media office burglary, the FBI mobilized thousands of men, flew agents in from other offices, and kicked off an operation code-named MEDBURG. In the burglary’s wake, J. Edgar Hoover, FBI director at the time, closed 103 of the FBI’s 538 field offices, suspended the Media office’s agent-in-charge without pay for a month, and eventually terminated the Cointelpro program on April 28, 1971 — just one month after the break-in.

Despite Hoover’s best efforts, the FBI couldn’t quash the leaked revelations, and the fallout eventually reached the Senate floor.

Partially in response to the documents released by the Citizens’ Commission, Idaho Democrat Frank Church headed an eponymous 1975 committee to investigate the activities of the FBI and the CIA. The “Church Committee’s” findings eroded public trust in America’s federal intelligence and law enforcement agencies. Decades later, that trust has yet to be fully regained.

The Church Committee ultimately became the Senate Intelligence Oversight Committee, a body that continues to provide guidance and mete out punishments when US agencies overstep their mandates and violate the law.

Read Next:

Lauren Coontz is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. Beaches are preferred, but Lauren calls the Rocky Mountains of Utah home. You can usually find her in an art museum, at an archaeology site, or checking out local nightlife like drag shows and cocktail bars (gin is key). A student of history, Lauren is an Army veteran who worked all over the world and loves to travel to see the old stuff the history books only give a sentence to. She likes medium roast coffee and sometimes, like a sinner, adds sweet cream to it.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.