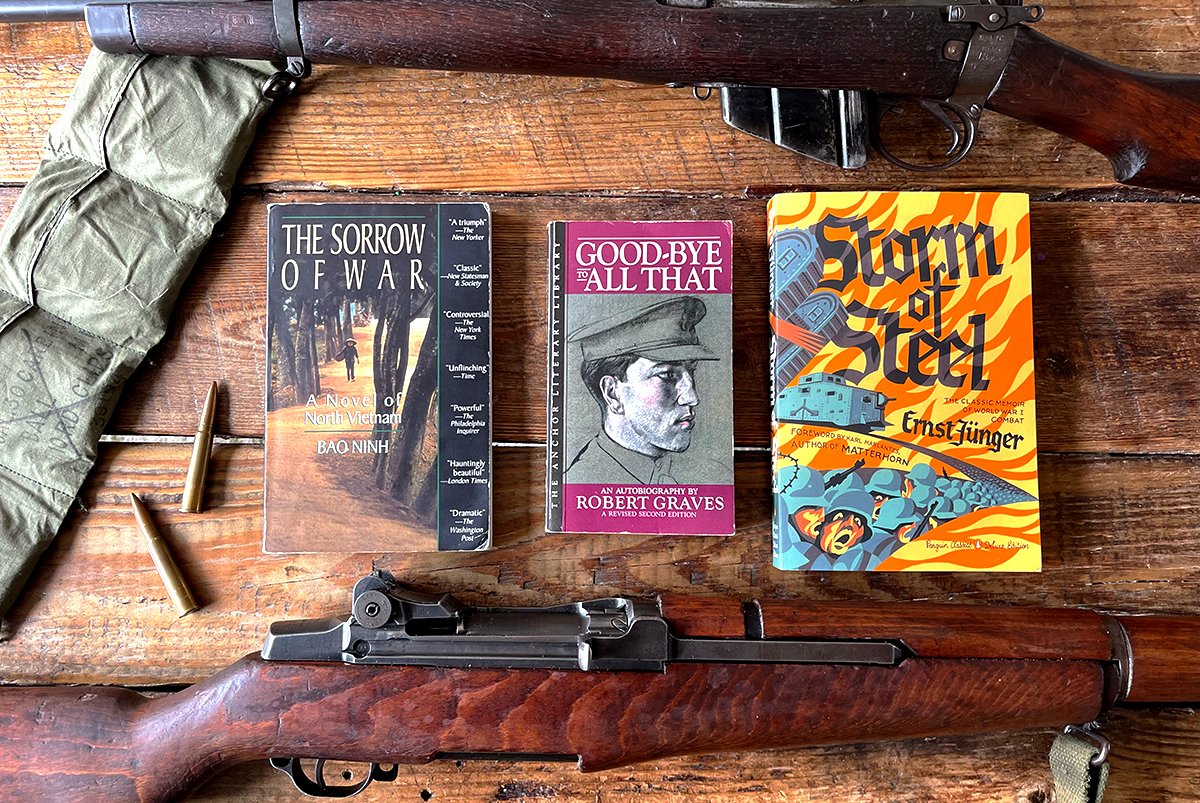

Three of the best war stories written by veterans who aren’t American. Photo by Mac Caltrider/Coffee or Die Magazine.

To conclude his combat memoir Beyond Band of Brothers, retired major and World War II veteran Richard “Dick” Winters reiterates the truism that war simultaneously brings out the best and worst in people. There are few mediums better for understanding the human experience of waging war than war memoirs and novels. Personal accounts such as With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa, Fields of Fire, and The Things They Carried fill the shelves of American warfighters, but too often, books written by veterans of other countries are overlooked in the United States. These are three of the best war stories written by veterans who aren’t American.

‘Storm of Steel’ by Ernst Jünger

First published in 1920, In Stahlgewittern, or Storm of Steel, is the World War I memoir of German veteran Ernst Jünger. Jünger — a stormtrooper responsible for leading raids into French and English trenches — fought in several major battles, including Champagne, the Somme, Guillemont, and Cambrai. He was wounded a staggering seven times, including gunshot wounds to the head and chest, and was one of only 11 German infantry officers to be awarded the Pour le Mérite: Germany’s highest award for valor. But it’s Jünger’s unflinching account of trench warfare that make him a man worth remembering.

Jünger’s account of WWI combat is unique in its complete lack of political commentary. He never mentions the causes of the war or reflects on the morality of the German cause. Instead, he simply writes about combat from the perspective of what Karl Marlantes — Vietnam veteran and author of Matterhorn — calls “a born warrior.”

He describes with uncommon neutrality the nightmarish type of intimate combat required to clear trenches. His descriptions of killing without remorse are rare for someone who regularly met the enemy at the close range of a revolver and knife.

“These moments of nocturnal prowling leave an indelible impression,” Jünger writes, describing what precedes hand-to-hand combat. “Eyes and ears are tensed to the maximum, the rustling approach of strange feet in the tall grass in an unutterably menacing thing. Your breath comes in shallow bursts; you have to force yourself to stifle any panting or wheezing. There is a little mechanical click as the safety-catch of your pistol is taken off; the sound cuts straight through your nerves. Your teeth are grinding on the fuse-pin of the hand-grenade. The encounter will be short and murderous. You tremble with two contradictory impulses: the heightened awareness of the huntsmen, and the terror of the quarry. You are a world to yourself, saturated with the appalling aura of the savage landscape.”

The 102-year-old book has withstood the test of time for the fact that it avoids broad strategies or even the outcome of the war. Rather than commenting on the meaning of it all, Jünger strictly adheres to describing life as a stormtrooper and remains politically neutral. Storm of Steel is a book for those more interested in warriors than war in itself.

‘The Sorrow of War’ by Bao Ninh

Bao Ninh served in the North Vietnamese army and later wrote The Sorrow of War — an unapologetic novel based loosely on his own experiences fighting in the decadeslong conflict. Ninh’s novel is rare in its ability to condemn war so convincingly from the vantage point of the victor. He describes defeats and victories as if there were no distinction between the two, critically asking whether one can really call a battle a victory when it requires such a high human cost.

The Sorrow of War eliminates perceived differences between American troops and North Vietnamese soldiers, stepping over motivations for the war and instead sharing the misery and suffering evenly.

“Victory after victory, withdrawal after withdrawal. The path of war seemed endless, desperate and leading nowhere,” Ninh writes in the same vein as Erich Maria Remarque. “The soldiers waited in fear, hoping they would not be ordered in as support forces, to hurl themselves into the arena to almost certain death.”

Vietnam War novels are a genre of their own, but almost all of the great stories written about the Vietnam War come from American veterans and journalists — The Sorrow of War changes that, providing a vital perspective.

‘Good-Bye to All That’ by Robert Graves

Robert Graves is best remembered as one of several prominent English poets to emerge from World War I. In addition to his poetry, Graves wrote a phenomenal memoir of his time in combat and his struggle to adapt to post-war life in England.

Often overshadowed by Siegfried Sassoon’s Memoirs of an Infantry Officer, Good-Bye to All That contains far less swagger and replaces those moments of personal heroism with direct criticism of the war. Graves proposes war is not a necessary aspect of national defense but a “sacrifice of the idealistic younger generation to the stupidity and self-protective alarm of the elder.”

Unlike other WWI writers, Graves doesn’t end his soldier’s story when the last shot is fired. He goes on to describe how war is rarely over for those who participated, even after peace agreements are reached and the armies go home.

“England looked strange to us returned soldiers,” he writes of his bumpy journey to reintegrate into English society. “We could not understand the war-madness that ran wild everywhere, looking for a pseudo-military outlet. The civilians talked a foreign language. I found serious conversation with my parents all but impossible.”

Graves seldom strays from his agenda of writing a vehemently anti-war book, but Good-Bye to All That goes deeper than most of the other anti-war books to come out of the trenches of WWI. His inclusion of other soldiers’ heroics bolster the authenticity of his account. He includes those moments of selfless sacrifice that permeate all wars and manages to do so without adding an unnecessary footnote to remind readers that, for all the bravery, war is still shameful.

“The first dead body I came upon was Samson’s. I found that he had forced his knuckles into his mouth to stop himself crying out and attracting any more men to their death. He had been hit in 17 places,” Graves writes of one of his comrades’ final act of selflessness.

His intentional omission of war’s waste in that passage reveals Good-Bye to All That to be a more honest account of the war than some of those written by Graves’ more outspoken anti-war contemporaries. There is no miscategorizing Graves’ memoir as anything other than anti-war, but it reads as a more genuine account that’s willing to include the best of humanity alongside the worst.

Read Next: America’s Longest War: 5 Essential Books About Afghanistan

Mac Caltrider is a senior staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. He served in the US Marine Corps and is a former police officer. Caltrider earned his bachelor’s degree in history and now reads anything he can get his hands on. He is also the creator of Pipes & Pages, a site intended to increase readership among enlisted troops. Caltrider spends most of his time reading, writing, and waging a one-man war against premature hair loss.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.