35 Years After Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster, Kyiv Seeks World Heritage Designation for ‘Exclusion Zone’

Former military buildings near the Soviet-era Duga-3 ballistic missile defense radar within the Chernobyl exclusion zone. Photo by Nolan Peterson.

KYIV, Ukraine — Monday marks 35 years since an explosion at reactor No. 4 at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant sent a plume of radioactive material into the atmosphere, fatally contaminating the nearby areas and sending radioactive fallout across Europe. The resulting fire lasted 10 days and released as much radiation as 400 Hiroshima bombs.

The April 26, 1986, disaster killed 31 plant workers and firemen in its immediate aftermath and likely was responsible for thousands more deaths, according to World Health Organization estimates. The 50,000 residents of the nearby town of Pripyat were evacuated two days after the nuclear accident.

In the runup to Monday’s anniversary, the Ukrainian government has kick-started an effort to have UNESCO — the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization —recognize the Chernobyl plant and its surrounding area as a World Heritage Site.

“We believe that putting Chernobyl on the UNESCO heritage list is a first and important step towards having this great place as a unique destination of interest for the whole of mankind,” Ukrainian Culture Minister Oleksandr Tkachenko told Reuters.

“The importance of the Chernobyl zone lays far beyond Ukraine’s borders,” Tkachenko said. “It is not only about commemoration, but also history and people’s rights.”

According to news reports, the Ukrainian UNESCO proposal may include the entire 20-mile Chernobyl “exclusion zone,” as well as the abandoned, Soviet-era Duga-3 ballistic missile defense radar facility.

The Chernobyl plant is located only about 67 miles north of Ukraine’s capital city of Kyiv. However, on May 1, 1986, just days after the nuclear disaster, the International Workers’ Day parade went ahead as planned in Ukraine’s capital city.

The Kremlin evidently was more concerned with keeping up appearances than dealing with reality. And so on that clear spring day, tens of thousands of people lined Kyiv’s roads, totally unaware of the radioactive fallout invisibly descending upon them.

Decades later, film shot during the parade sparkles and flashes — evidence of radioactive particles on the celluloid.

Today, Chernobyl’s so-called “exclusion zone” extends out along a radius of almost 20 miles from reactor No. 4.

The site has become a major tourist attraction in Ukraine, particularly after the popular 2019 HBO miniseries depicting the 1986 disaster. In 2019, roughly 124,000 tourists visited the Chernobyl exclusion zone, according to the State Agency for Management of the Exclusion Zone.

Tour groups travel within a quarter of a mile of the destroyed reactor, which is cocooned under a concrete sarcophagus and a metal containment dome.

Yet, scattered throughout the exclusion zone is evidence of the seriousness of the nuclear disaster’s fallout. Above all, the abandoned town of Pripyat is a ruin, slowly decaying as nature takes its toll.

Once home to some 50,000 people, the ruins of Pripyat are now a case study in the unstoppable entropy of nature. The roads are overgrown with trees and grass, and the concrete buildings are crumbling.

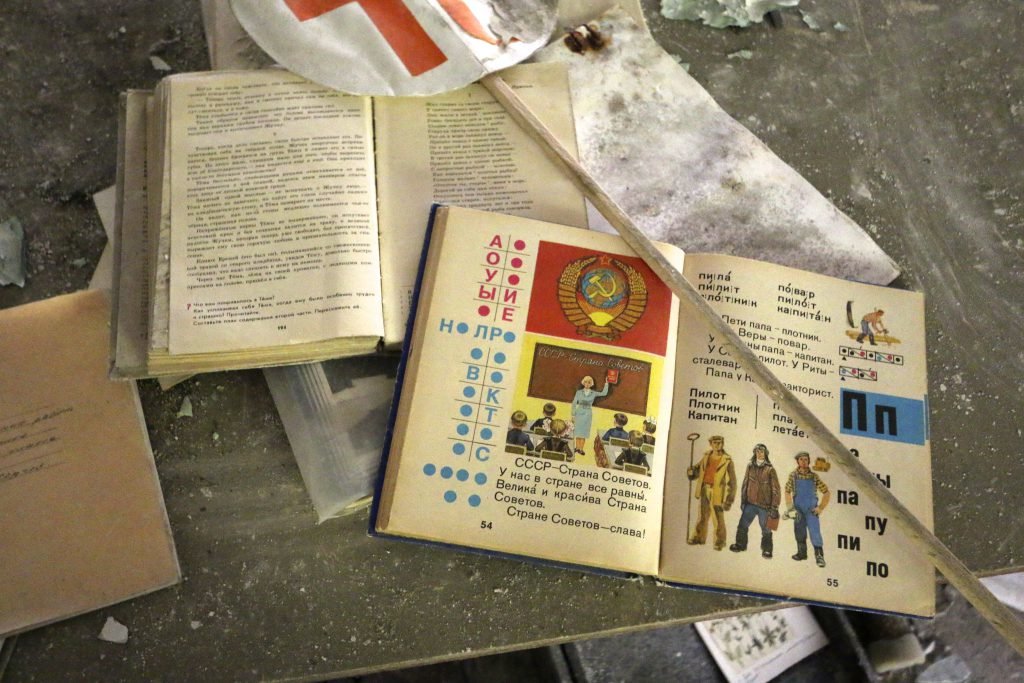

The abandoned town is also a snapshot of life at the tail end of the Soviet Union’s life span, frozen in the time and day of the 1986 nuclear disaster.

On the ground floor of the local community center, posters of Vladimir Lenin still hang from the walls. In an abandoned school, textbooks dating from the 1980s are covered in dust.

About 6,000 people work within the Chernobyl exclusion zone on a rotational basis. Entrants are required to follow strict protocols to prevent radiation contamination. Workers’ shifts are limited to either four or 15-day stints.

Anyone exiting the radioactive areas is required to go through radiation inspection points located 10 and 30 kilometers from reactor No. 4. Contaminated clothing or shoes are confiscated, and there is a facility on site to quarantine individuals whose level of radioactivity exceeds the threshold considered safe for exit.

Today, reactor No. 4 is covered by a 100-foot-tall metal cocoon called the Chernobyl New Safe Confinement, which was completed in 2019 and should contain the radiation for 100 years.

While radiation levels are highest in the immediate vicinity of reactor No. 4, they do not diminish uniformly by distance. The exclusion zone is dotted with radiation “hot spots,” where radioactive material has accumulated.

Geiger counters periodically chime their alarms when passing through these seemingly random pockets of radioactivity, which can be more than 100 times normal levels.

Within the exclusion zone, nature has overtaken the remains of villages and settlements abandoned in the days after the disaster. A herd of horses, brought in to tramp down grass to reduce the risk of forest fires, has thrived. Rabbits, deer, and other wildlife roam the forests.

“Chernobyl is a unique place on the planet, where nature revives after a worldwide man-made disaster,” Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy said in 2019. “We should show Chernobyl to the world: scientists, environmental specialists, historians, and tourists.”

Read Next:

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.