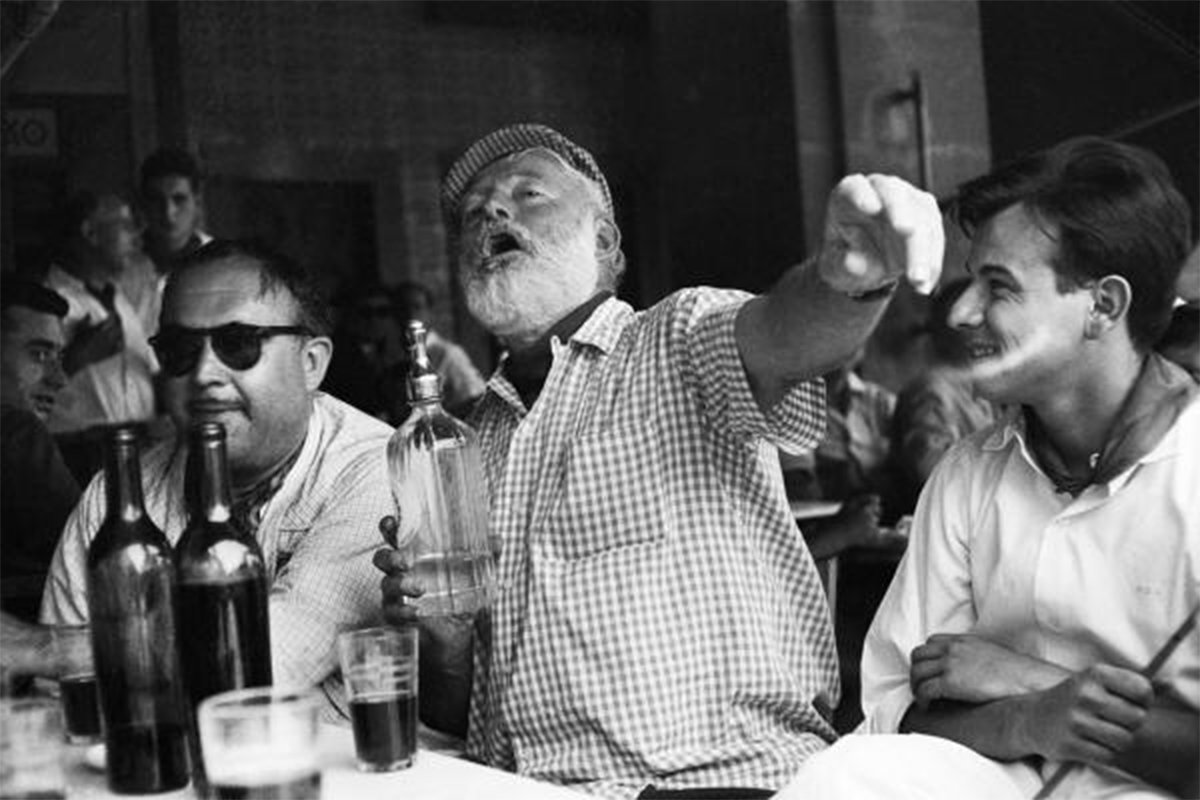

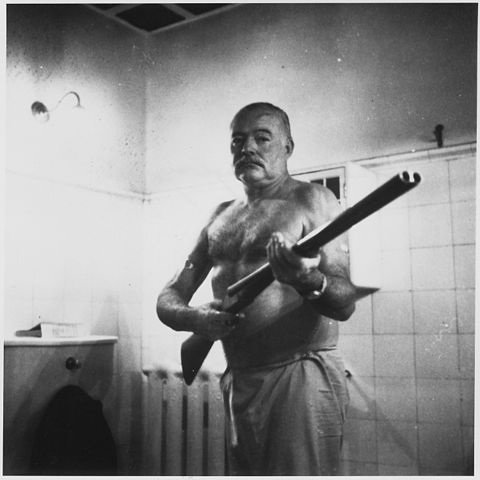

Ernest Hemingway is a near-mythic figure in 20th century American literature, and for good cause. From accompanying Patton’s army in the Second World War, to fishing off the shores of Cuba, Papa and his adventures have been read by millions and inspired even more.

Hemingway’s life of adventure isn’t what distinguished him though; his simple and straightforward prose and engaging dialogue carried stories that struck to the core of the human experience. That the common man could identify with his lust for excitement, desire for a good drink, and trouble with their spouse made his storytelling even more approachable, and in turn, his work even more famous.

Of course, nearly everyone has heard at least some of his more famous lines. I don’t know a single person who has been to war that hasn’t seen Hemingway’s potent take on how bland life can seem after the thrill of war: “There is no hunting like the hunting of man, and those who have hunted armed men long enough and liked it, never care for anything else thereafter.”

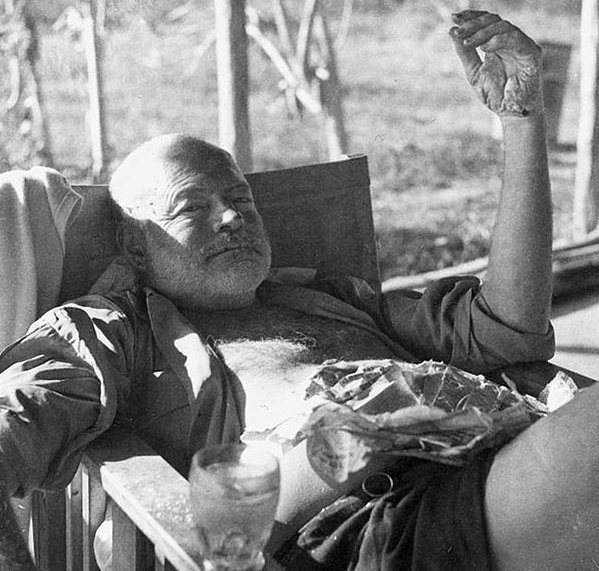

And if you told me a fellow writer hasn’t heard Hemingway’s infamous advice on writing — “write drunk, edit sober” — then I’d respond that either that person is a liar or they aren’t even a writer at all. Indeed, his work borders on fetish for many modern wordsmiths who try to emulate his simple prose, constantly trying to find the right balance of blue collar words that still find a way to impact readers of any background, just like a common kitchen knife that cuts deep regardless of who holds it. This wordsmith would argue that task is easier said than done.

Although his storytelling was in a class of its own, his life wasn’t perfect. Despite many who would like to romanticize his journey (again, myself included), Hemingway grappled with alcoholism, depression, multiple marriages, and paranoia. But those are the stuff of real life and, coupled with the other aspects of life, put him in a unique position to offer advice worth listening to.

That being said, here’s a few quotes on life and what it’s really like from the man who created his own myth that eventually became legend. If you’re so inclined, you might find more than a few lessons in these words.

In 1925, Hemingway wrote the short story “Soldier’s Home.” In one passage, he describes a U.S. Marine returned from war. “At first Krebs, who had been at Belleau Wood, the Champagne, Saissons St. Michiel and in the Argonne did not want to talk about the war at all. Later he felt the need to talk but no one wanted to hear about it. His town had heard too many atrocity stories to be thrilled by actualities.”

I don’t think Krebs’ experience is unique. If you fought in the Global War on Terror but didn’t kill a hundred men, commit an act that haunts you, or otherwise distinguish yourself in some way that shocks the common citizen, then did it really matter? Does anyone care about your experience? If not, why do you care that they don’t care? It’s a passage that inspires introspection, and not just for warfighters, but anyone who has experienced trauma.

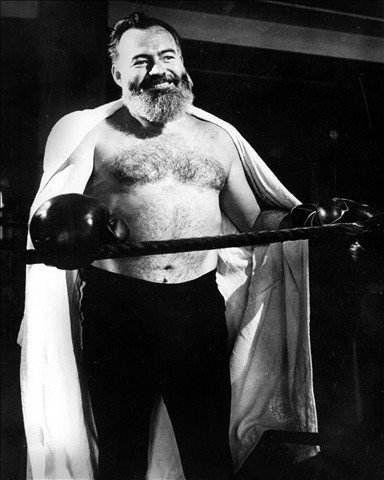

In 1927, The Atlantic published a short story by Hemingway titled “Fifty Grand.” The tale is about Jack Britton and how he trained for and eventually fought Jimmy Walcott in a boxing match. Although there are many great lines in this piece, the one that stands out to me exemplifies the duality of what we show the public and what reality actually is. Hemingway writes, “This is all great for the crowd. How gentlemanly the boys are before the fight. How they wish each other luck.”

Hemingway writes this after describing Britton and Walcott putting on a show of good sportsmanship for the crowd as they enter the ring, while simultaneously having an under-the-breath exchange that is much less pleasant. Some might call this behavior fake, or at least disingenuous. Hell, in today’s media landscape, the crowd would be much more entertained by the unpleasantries than the show of good sportsmanship. But I would call it an example of how most have to live: putting on a good face for those around us while silently cursing the world.

But of course, one should not be consumed by what the masses think — or need, for that matter.

“If you serve time for society, democracy, and the other things quite young,” Hemingway wrote in “The Green Hills of Africa,” “and declining any further enlistment make yourself responsible only to yourself, you exchange the pleasant, comforting stench of comrades for something you can never feel in any other way than by yourself.”

I don’t know who needs to hear this, but if you feel like you’ve never lived for you, then take Hemingway’s advice and pursue happiness in a way that is completely independent of anyone else and is yours alone to bathe in the enjoyment thereof. I don’t know how, but I think in his words one might find the cure to all that ails them.

In 1933, Hemingway wrote a stirring and casually disturbing piece titled “A Natural History of the Dead.” Much of the story is devoted to observations of corpses, largely due to the effects of war. But one passage strikes deep, especially for anyone who has the misfortune of knowing all too well the difference between natural and unnatural death. “The only natural death I’ve ever seen, outside of loss of blood, which isn’t bad, was death from Spanish influenza. In this you drown in mucus, choking, and how you know the patient’s dead is: at the end he turns to be a little child again, though with his manly force, and fills the sheets as full as any diaper with one vast, final, yellow cataract that flows and dribbles on after he’s gone.”

“… at the end he turns to be a little child again …” Those words are true for anyone who has helplessly watched a soul realize that it will depart the body soon, and that the luxury of an unexpected death won’t be granted on this try.

Of course death conjures thoughts of time and how finite it is. There’s never enough of it, and if only we could reverse it or slow it down or fuck do anything to manipulate it in our favor! But that’s not the way it is, and Hemingway knew that. In a written letter to Lillian Ross in 1950, he scribbled truth in raw form: “Time is the least thing we have of.”

Marty Skovlund Jr. was the executive editor of Coffee or Die. As a journalist, Marty has covered the Standing Rock protest in North Dakota, embedded with American special operation forces in Afghanistan, and broken stories about the first females to make it through infantry training and Ranger selection. He has also published two books, appeared as a co-host on History Channel’s JFK Declassified, and produced multiple award-winning independent films.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.