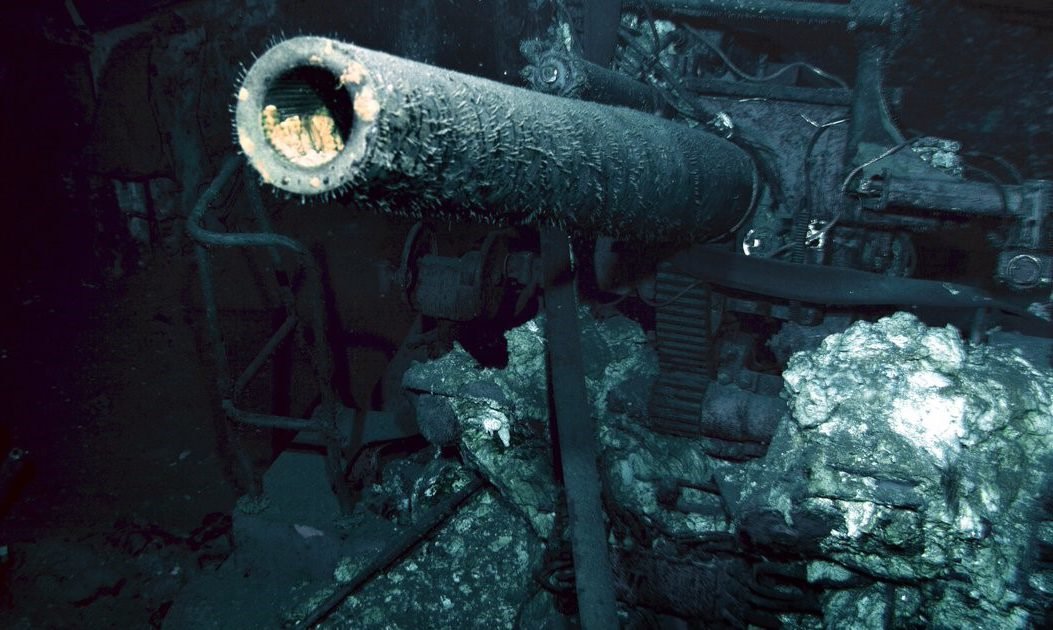

One of the unmistakable 5-inch guns protruding from the wreckage of the Indianapolis. When the ship was found in 2017, the ship’s bell and anchor were also positively identified. Photo by Paul G. Allen, courtesy of Navigea Ltd R/V Petrel.

Perhaps as many as 10,000 ships were sunk in battle on the high seas during World War II. Most remain undiscovered, but some of the most famous ships lost in the conflict have been found in their final resting places. Their sunken hulls are considered tombs for those who never came home. Here are several of the most famous wrecks that explorers have found, some of which are in danger today from illegal salvaging operations.

HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales

The battle cruiser HMS Repulse, heavy cruiser HMS Prince of Wales, and an escort of destroyers made up the components of “Force Z,” steaming into the Pacific on direct orders from British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Adm. Tom Phillips.

Japanese bombers discovered Force Z around 2:20 a.m. on Dec. 9, 1941, just a day after it had left port in Singapore. According to Bloody Shambles, the Japanese launched 86 fighter planes armed with bombs and torpedoes from a base in Vietnam.

As the Japanese attacked, the Repulse was able to outmaneuver 19 torpedoes but was hit by four. It capsized and sank, killing 508 of those aboard.

The Prince of Wales was one of England’s most famous ships, having been one of the victors over the feared German battleship Bismarck earlier in the war. But against the Japanese airpower, it took a torpedo to its left side and a bomb to the catapult deck, ultimately dragging 317 men down as it capsized and sank beneath the Pacific.

HMS Electra and HMS Vampire rescued the 796 survivors from the Repulse and the 228 survivors from the Prince of Wales.

The Repulse and the Prince of Wales both sank in the South China Sea, off the coast of Malaysia. Though the exact locations of the wrecks are protected, explorers have found evidence of damage to the wrecks from illegal salvage operations.

AHS Centaur

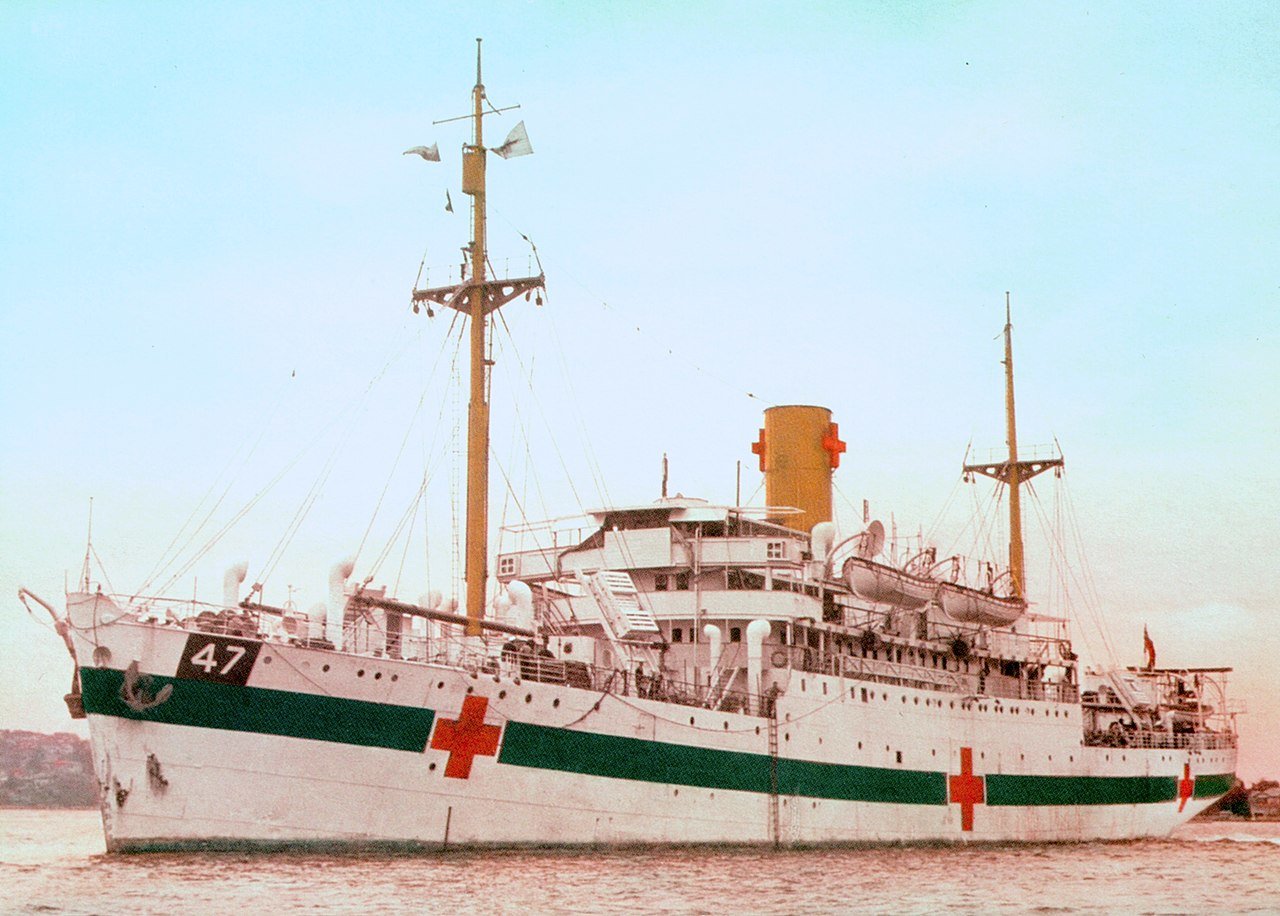

In WWII, many hospital ships of both the Allies and the Axis were sunk, despite clear rules against targeting them. In most cases, the attackers claimed that the distinctive markings — often red crosses — on the hospital ships were hard to spot from planes or far-off ships. But the submarine that sank Australian Hospital Ship Centaur could make no such excuse.

The Swiss specifically informed Japanese officials in February 1943 that the Centaur was going to be commissioned as a hospital ship, complete with three massive red crosses and a thick band of green paint that went all the way around the hull. It would have been impossible to mistake the vivid colors against a white background through a periscope.

On May 14, 1943, the Centaur was traveling from New Guinea to Townsville, Australia, evacuating wounded troops. The brightly lit Centaur was alone, and against a clear night with no warship escort, it must have looked like an easy target to Capt. Hajime Nakagawa, commander of Japanese submarine I-177, the probable culprit. The submarine fired a single torpedo to the Centaur’s left side around 4:10 a.m.

The Centaur sank so quickly that there was no opportunity to abandon ship or release any lifeboats. Only 64 survived of the original 332 aboard, including just one nurse, Sister Ellen Savage.

David Mearns, an American oceanographer, found the wreck of the Centaur in 2009 off the coast of Queensland, Australia. Mearns’ expedition laid a memorial plaque on the bow.

USS Indianapolis

We could tell you what happened to the Indianapolis, but why would we, when we can let Robert Shaw do it?

“Japanese submarine slammed two torpedoes into her side, Chief. We was comin’ back from the island of Tinian to Leyte. We’d just delivered the bomb, the Hiroshima bomb. Eleven-hundred men went into the water. Vessel went down in 12 minutes.”

The story Shaw’s Capt. Quint immortalized in Steven Spielberg’s Jaws is true, including the terrifying details of shark attacks. Japanese submarine I-58, commanded by Capt. Mochitsura Hashimoto, torpedoed the USS Indianapolis just after midnight on July 30, 1945. Of the nearly 1,200 aboard, about 300 died in the initial sinking. But over the course of the next four days, saltwater poisoning, exposure, dehydration, and — famously — sharks would leave only 316 to be found alive by a Navy plane.

The errors — both on board and by Navy officials in the aftermath — that left the survivors alone for so long are a lesser-known part of the story.

The Navy cited “radio silence” as the primary reason no rescue was immediately launched. However, “at least three ‘SOS’ messages were received separately, but none were acted upon because one commander was drunk, another had ordered his men not to disturb him and a third thought it was a Japanese prank,” Timothy Maier said.

Eventually, the Navy court-martialed the Indianapolis’ captain, Charles McVay III, for “failing to zigzag.” McVay took his own life in 1968 because of the guilt he carried over the tragedy. His court-martial was cleared in 2001, and McVay was absolved of all wrongdoing.

The wreckage of the USS Indianapolis was found in August 2017 by an expedition funded by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen.

USS Houston and HMAS Perth

In the early hours of March 1, 1942, the USS Houston and the HMAS Perth simply disappeared from the Java Sea.

The previous day, the ships had left Jakarta, Indonesia, still low on fuel and ammunition from participating in the Battle of the Java Sea that February, the largest battle between surface ships since the Battle of Jutland in World War I.

The two cruisers needed to escape to the Indian Ocean, understanding that another combat encounter in their vulnerable state could be their last. As Houston and Perth entered the Sunda Strait on the northern tip of Indonesia, they were surrounded by Japanese submarines and battleships. Four torpedoes sank the Perth just past midnight, and four more took Houston at around 1 a.m. Just 368 men, or about one-third of Houston’s crew, survived, while 324 from the Perth survived. Nearly all were captured and sent to prison camps, except for four sailors who made it to land the night of the battle and were never caught.

The wreckage of the Perth was found in 1967, and the Houston’s in 2014. In 2017, investigators confirmed that both had been victims of illegal salvage operations.

Read Next: Colombian Mercenaries Suspected in Haiti Assassination Have US Military Ties

Lauren Coontz is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. Beaches are preferred, but Lauren calls the Rocky Mountains of Utah home. You can usually find her in an art museum, at an archaeology site, or checking out local nightlife like drag shows and cocktail bars (gin is key). A student of history, Lauren is an Army veteran who worked all over the world and loves to travel to see the old stuff the history books only give a sentence to. She likes medium roast coffee and sometimes, like a sinner, adds sweet cream to it.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.