191006-N-VI515-0396 SOUTH CHINA SEA (October 6, 2019) Ships from Ronald Reagan Carrier Strike Group and Boxer Amphibious Ready Group sail in formation while conducting security and stability operations in the U.S. 7th Fleet area of operations. U.S. 7th Fleet is the largest numbered fleet in the world, and the U.S. Navy has operated in the Indo-Pacific region for more than 70 years, providing credible, ready forces to help preserve peace and prevent conflict. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Erwin Jacob V. Miciano)

U.S. Navy SEALs have a long and extraordinary history of valor, heroism, and badassery. Their reputation has enjoyed the limelight on bookshelves and in movie theaters around the world — while other units and legendary exploits are tucked away into the confines of hidden history.

Today is the Navy’s 244th birthday, and we wanted to take a look at some of the badass Cracker Jacks who never went through BUD/S. From the founder of an elite psychological warfare unit during World War II to a prisoner of war (POW) who jumped off a moving train to athletes with more than just home runs and touchdowns on their highlight reels. These heroic men and women are on this list not for just surviving impossible odds and enduring untold danger, but also for the impact they had on historical innovations and cultural traditions.

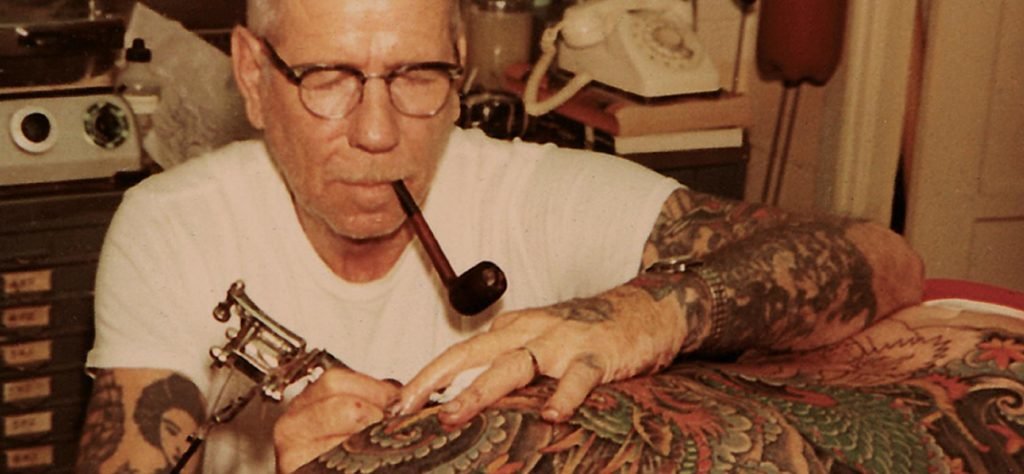

Sailor Jerry

Far and wide, Sailor Jerry was known to be a rough-and-tumble Renaissance man with a tobacco pipe hanging from his lip, a tattoo machine in hand, and a mind that dipped into the fray of a rogue misfit. In his early teens, when he went by his given name Norman Collins, he traveled the country by hitchhiking and train hopping. The life of a tramp was far more than the wanderlust one expected from reading the newspapers. Train-hopping freights was dangerous. The outside world viewed them as pariahs, and law enforcement officers often threw them behind bars, but on the road is where Collins learned his craft. His one-poke primitive methods took skill, especially considering all were freehand, black-ink tattoos.

When in town, tramps often worked along the railroad to make cash to fund their lifestyle. In Chicago, Collins met and became the protegé of Gib “Tatts” Thomas, who taught him how to work a tattoo machine. Collins paid tramps he met along the railroad with cheap wine in exchange for their skin so he could practice. Vying for adventure across the sea, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy in 1928, where his name would evolve into legacy. His travels to Southeast Asia introduced him to Chinese and Japanese cultures, for which he developed a fondness. After leaving the Navy, he took his knowledge of art back to Honolulu, Hawaii, where he opened his first tattoo shop in the Hotel Street district.

This area was a party scene for sailors and U.S. Marines who were on shore leave before deploying to fight during World War II. Those who didn’t frequent bars and brothels received tattoos from the legend himself. It was the epicenter for the renegades. Sailor Jerry’s designs were often copied by what he referred to as “brain-pickers,” but many knew their true origin. The scantily clad pin-up girls, nautical stars, anchors, dragons, sharks, and other animal anatomy all had deeper meanings steeped in sailing traditions.

Swallows were heavily associated with the badge one wears when they’ve sailed 5,000 miles. There was also the moral and spiritual meaning that when a sailor dies at sea, his soul is carried by birds to heaven. Pig and rooster tattoos were based on superstitions — when a vessel is struck and the inhabitants have to abandon ship, pigs and roosters in buoyant wooden cages have a surprisingly high survival rate. For good luck, sailors would get a pig tattooed on top of their left foot and a rooster on top of their right.

After the war, Sailor Jerry captained a three-master schooner and was a disc jockey on his own radio show called Old Ironsides. He played in a jazz band and toured between shows in a canary-yellow Thunderbird. One afternoon while riding his Harley Davidson, he had a heart attack — but he got back on his bike and rode home. A year later, in 1973, he suffered another heart attack and died. His protegès Ed Hardy, Mike Malone, and Kazu Oguri took over his tattoo parlor, and his legacy lives on through his artwork on military veterans’ skin, his iconic designs, and the Sailor Jerry Spiced Rum.

Captain Slade Cutter

When Slade Cutter showed up at the U.S. Naval Academy, his dream was to be a professional flutist. He was certainly good enough, even winning an interscholastic flute competition judged by John Philip Sousa — yes, that Sousa, the enigmatic U.S. Marine Corps Marching Band composer. Ultimately, though, this dream evolved into more of a vice than a career. Seriously — in his Naval Academy yearbook, he listed his major vices as tobacco, swearing, and flute.

At 6-foot-2 and 215 pounds, Cutter was recruited to the college football team by Paul Brown of the Cleveland Browns. As a one-platoon player, he played every down, including special teams. This leatherhead jabbed defensive ends, blitzing off the edge as a reliable offensive linemen, only to switch gears and do the same chasing opposing quarterbacks. One of the great team memories occurred in the 1934 matchup with the U.S. Army. Cutter kicked the winning 20-yard field goal to bring the midshipmen a 3-0 victory — their first win over the Army in 13 years.

Upon graduation, he served as a college football coach. The day after the attacks on Pearl Harbor, Cutter and his crew aboard the USS Pompano came in to inspect the damage and found the battleship Utah upside down, the Arizona burning, and the Helena on her side. In an oral interview with Pickett Lumpkin, Cutter said they didn’t expect an air attack on Pearl Harbor, but they did prepare for midget submarines to attack from the channels.

Cutter completed three war patrols as an Executive Officer and conducted surveillance off the Wake and Marshall Islands. But it was his next post — as the Commanding Officer on the USS Seahorse — where he really proved himself.

Cutter led his crew on four war patrols and earned a Navy Cross for each of them, but he remained a humble leader. “The Seahorse sank 19 enemy ships during the four war patrols I was the skipper,” said Cutter. “The crew got the job done. I was merely the coordinator. They were brave and talented, and I never had to be reckless. I thought of the lives of those fine men, and frankly, I was aboard, too.” During one mission, Cutter and his crew, operating under their “Fuke’em Let’s Go!” motto, evaded three Japanese escort ships by dropping depth charges and completely wiped out an enemy convoy in 82 hours.

Throughout their war patrols, Cutter and his crew destroyed 23 enemy warships (though four were unarmed, so he personally only credits 19) and 142,000 tons of war materials. After he left his command, Cutter became the athletic director for the U.S. Naval Academy and was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1967.

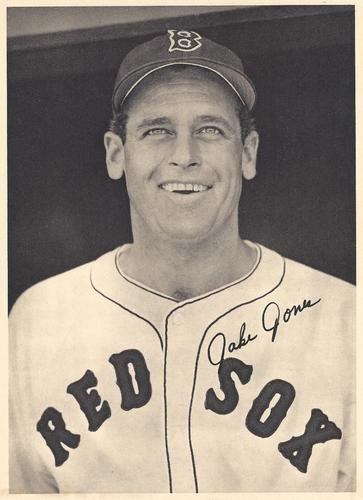

Jake Jones

Jake Jones was certainly not a household name, and his height would be the most noticeable thing about him if someone saw him on the street. The Louisiana native stood 6-foot-3 and was a promising semi-professional baseball player. He routinely kept his batting average above .300, which is no small feat. The Chicago White Sox called him up to the majors for a cup of coffee (three hitless games) before he was sent back to the minors. In 1942, as American involvement in World War II gained mobilization, Jones enlisted in the U.S. Navy as an aviation cadet. He was then commissioned as an Ensign with the hopes of becoming a pilot.

Sent to the Pacific aboard the USS Yorktown — which was nicknamed “The Fighting Lady” for its reputation during the Battle of Midway — Jones piloted the Grumman F6F Hellcat with extraordinary skill. “[He’s] a great guy and one of the best flyers I had ever saw,” said one of Jones’ teammates to Grantland Rice, who is considered one of the finest sportswriters. In November and December 1944, Jones received two Air Medals for destroying enemy shipping installations on the ground in the Philippines, in addition to shooting down one Japanese plane, severely damaging another, and causing a third to escape.

In January 1945, for combat operations across Formosa, China, French Indo-China, and Nansei Shoto, Jones earned two more Air Medals. On January 21, he braved incoming anti-aircraft fire while dispatching a large oil tanker with rockets. This action earned him his first Distinguished Flying Cross. In February 1945, Jones and his wingman launched an inland attack over Tokyo, where he earned his title as an ace by downing five Japanese fighters in two days. On February 16, three Japanese aircraft zeroed in on him, but he downed every one of them. The duo exploded six enemy hangars by making low-level strafing runs and rocket attacks.

On his return flight to the Yorktown, Jones later told his son, his wing had a gaping, man-sized hole right through it, a close call that nearly took his life. His final war tally included seven Japanese aircraft shot down, four Japanese ships sunk, and several mainland installations damaged. He took home a chestful of medals that included two Distinguished Flying Crosses, a Silver Star, and four Air Medals, making him one of the most decorated ball players during the war.

After the war, Jones kept one foot in baseball and the other in the Navy. He trained pilots before they went off to fight in Korea, and finished his career on the diamond with the White Sox and Boston Red Sox.

Douglas Fairbanks Jr.

The son of a Hollywood heartthrob — and a movie star in his own right — Douglas Fairbanks Jr. is remembered as “the father of the U.S. Navy Beach Jumpers,” the covert psychological warfare and deception unit that used tricked-out speedboats on secret missions to confuse coastal defensive positions during World War II. After completing an officer-exchange augmentation with British commandos at their schoolhouse in Scotland, Fairbanks uncovered the effectiveness of small unit deception and tactical cover. The Beach Jumper program was built from the ground up with the concept of jumping from beach to beach, just as their namesake entails.

On July 10, 1943, they launched a mission off the coast of Cape San Marco, Italy. Several customized Air Sea Rescue (ASR) boats bounced through the waves at top speed. Carrying six enlisted sailors and one officer, the boats used smoke generators to provide a man-made layer of fog to shield their infiltration. When they were 3,000 meters from the shore, their twin .50-caliber machine guns opened up, time-delay smoke pots exploded off the sides of their boats, rockets were shot through the air, and loudspeakers blasted the sounds of war — all to disguise the intent of an all-out beach invasion. The were creative, too, and towed balloons with a radar signature that emitted the size of a large vessel.

The goal was to create as much commotion as possible to draw enemy troop mobilization away from the real target, which was hundreds of miles away. The ingenious faux amphibious landings proved to be successful throughout World War II and helped confuse Axis-strategists long enough to successfully conduct much larger operations such as Operation Husky in Sicily.

Fairbanks also led a group of Beach Jumpers on another mission as a part of Operation Dragoon off Southern France, where one of his small boats was diverted when two heavily armed German Corvette battleships intercepted it. Fairbanks directed the rest of his force, successfully destroyed both enemy warships, then coordinated the rescue of their crew. He was awarded the Legion of Merit with Combat “V” for his actions. Fairbanks retired as a captain in the Navy in 1954 and returned to his acting career, earning three stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for film, television, and radio. He died in 2000.

Agnes Meyer Driscoll

A badass doesn’t always have to lead the way with brute force — the ability to outthink and outwit the enemy wins battlefield skirmishes and wars, too. Agnes Meyer Driscoll used her intuition to decipher enemy codes and dismantle the most sophisticated signals during World War I and World War II.

Joining the Navy in 1918, she became known as “the first lady of naval cryptology.” Driscoll held a degree from Ohio State University and pursued technical and scientific studies, which was rare for women during this time. Assigned first to the Postal and Cable Censorship office in Washington, she inspected mail for possible links to espionage. Later, she worked for the Code and Signal section, where she helped create the then-modern U.S. Navy cipher machines and codes. Her peers would come to call her Madame X or Miss Aggie.

In the 1920s, the U.S. Navy obtained a stolen photograph, which showed the code for the Japanese Navy’s fleet called Red Book. Driscoll recovered the superencipherment and used it to break Blue Book, Red Book’s replacement, in the 1930s. Her team uncovered nearly 85,000 code groups during these years, which had a major impact on understanding Japan’s knowledge of American naval planning in the Pacific. The Japanese did not replace Blue Book until 1938, when it became the Black Book.

In 1935, Driscoll helped smash the codes for the Japanese M-1 cipher machine (nicknamed ORANGE). ORANGE was used globally by Japanese attachés and was a critical component for secret messages between attachés and field operatives. As a result, two American moles were apprehended for passing information to the Japanese. Two years later, she solved the “5-num” component of the JN-25 system, a previously impassable cipher that included three separate code books, a 300-page book of random text, and a book of instructions. It consisted of 30,000 five-number groups that substituted for names, places, and dates. Fully exploited by 1942, it provided an early warning for the June attack on Midway Island.

Later in her extraordinary career, Driscoll worked for two years trying to crack the German enigma machine, unaware that the British had already tried their manual methods. Following the war, she played a key role in the formation of Armed Forces Security Agency, which transformed into the National Security Agency in 1952. She pored over every detail with a magnifying glass and valued doing her job manually, which has paid dividends for modern cryptologists attached to shadowy JSOC units in a revolving battlespace. In 1959, Driscoll retired at the mandatory age of 70 years old, with over 30 years of service.

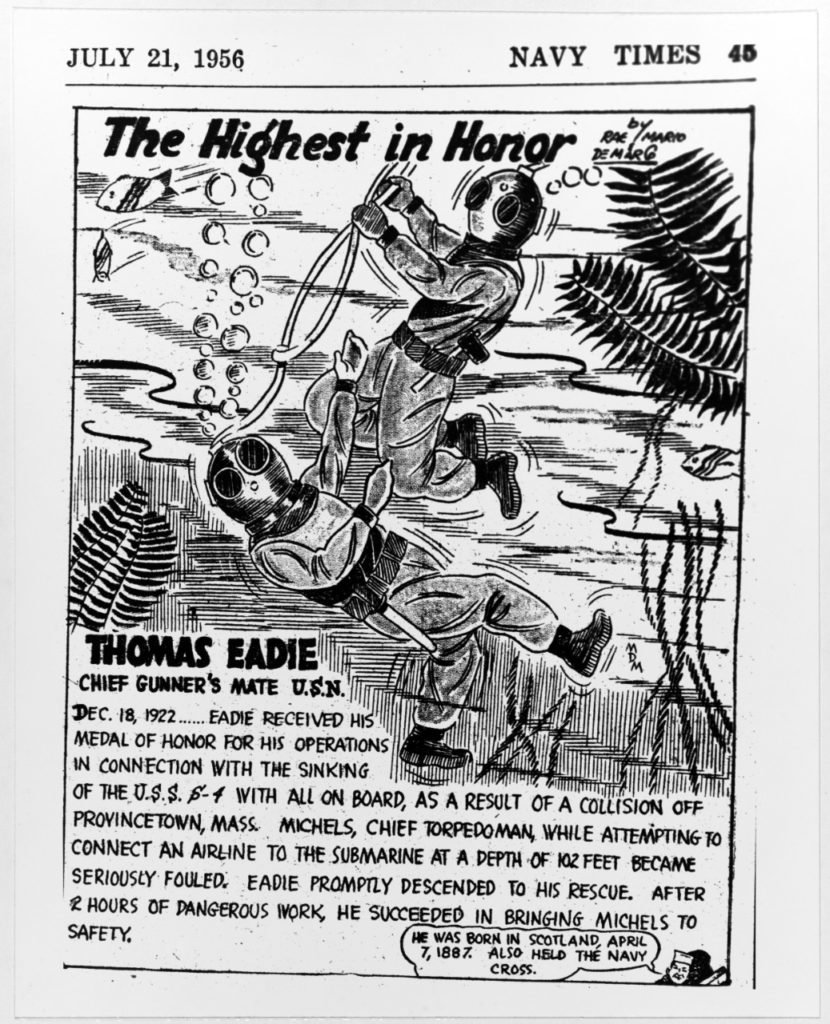

Thomas Eadie

“Rammed and sank unknown submarine off Wood End, Provincetown,” the radio message from the U.S. Coast Guard Destroyer Paulding alerted. As a result of the collision, all 39 crewmen and one civilian would perish aboard the USS S-4 (SS-109) submarine in the icy December waters off the coast of Massachusetts. Six crewmen remained trapped in the torpedo room, and those above the surface aboard the USS Falcon scrambled to their rescue. Experienced Navy Diver Thomas Eadie, who had already been recognized with a Navy Cross for raising the S-51 submarine in 1925, volunteered for this mission.

Weighted down with 200 pounds of diving equipment, he entered the water and descended with a lifeline and air hose attached to his rig. Through the murky brown water, Eadie reached the submarine, which was resting on the ocean’s floor 102 feet below. His weighted boots clanged against the medal frame of the vessel as he inspected the damage. The battery room had a gaping hole in it, but one officer and five enlisted sailors were trapped. He surfaced and gameplanned how to rescue the men still trapped in their steel coffin.

It was first determined to use the S-4’s ballast tanks to raise the submarine, a technique used in previous years. However, all of the tanks were damaged. A second plan called for a diver to connect an air supply to the submarine’s valve to buy them some time. Diver Fred Michels volunteered for the job, despite the increasing windy conditions as a storm rolled in. With 50mph winds and rocky waves, he plunged to the wreckage, but his lifeline and air hose had tangled in the conditions. To make matters worse, his dive suit had been punctured and freezing ice water entered his suit. Michels begged for assistance from the surface as he could no longer move.

Eadie had been resting in his room when the skipper alerted him of the news. He volunteered a second time, waited next to Michels for a hacksaw to be lowered down to him, and began the arduous process of cutting through the thick iron lines for the next two hours until he was free. Frigid water had entered Michels’ diving dress up to his neck, and he was hyperthermic. The crew pulled on the lines; the pair surfaced and was immediately rushed into decompression chambers. Both survived, but the crew in the torpedo room never made it out. For his heroism in rescuing his dive buddy, Eadie earned his second Navy Cross and the Medal of Honor.

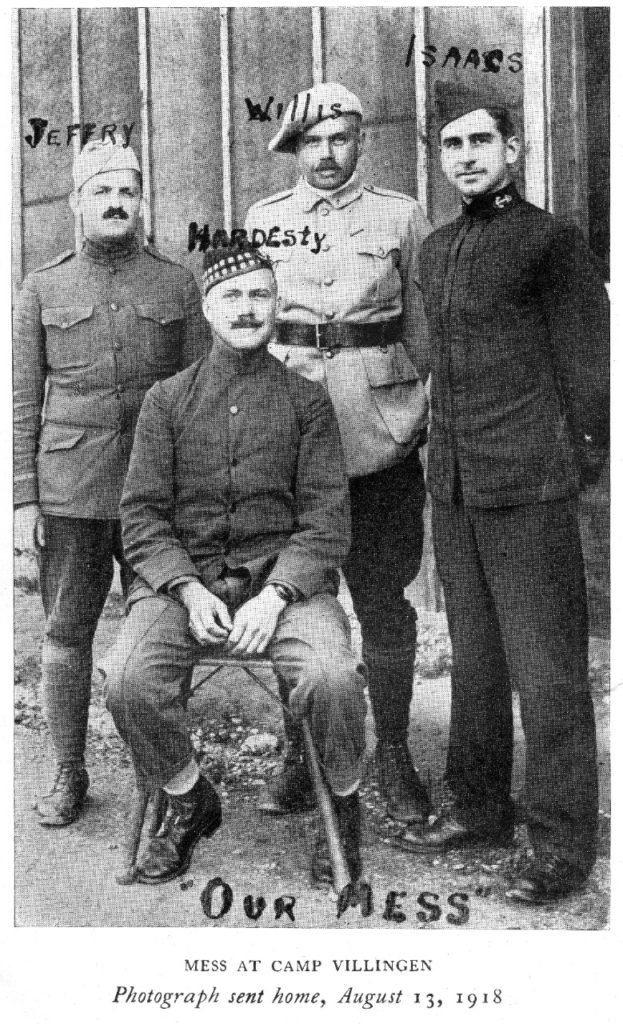

Lieutenant Edouard Izac

On May 31, 1918, the USS President Lincoln, a cruise-liner transformed into a man-of-war, was preparing to make its return home when it was sunk off the coast of France. Lieutenant Edouard Izac was captured by a German U-boat (U-90), but the Germans didn’t expect Izac to be fluent in their native language. Izac, who was born on Dec. 18, 1891, had German parents, but he kept this information to himself to gain intelligence on the Germans. They freely spoke about battleplans and strategic movements, including the terrifying breach in American security of Allied naval planners releasing armed escorts of troop transports too early. This cost several of his men their lives the day before.

On June 1, two American destroyers spotted the U-90 and gave chase. The German skipper, named Remy, issued the order to dive to 200 feet. Twenty-two depth charges filled with 300 pounds of TNT plopped into the water nearby, and Izac described the explosive concussion as “like a dog shaking a rat, and it was anything but pleasant to be the rat.” The U-boat escaped unscathed and docked in the Baltic Sea. He and some of the captured crew went up top for a smoke break. Izac later recalled that he tried to jump into the water to get picked up by a nearby vessel, but Remy, who shadowed his every move, grabbed his arm to prevent him.

Later, Izac was aboard a prisoner train transporting him to an inland POW camp, Villigen, Baden. He jumped through an open window on the speeding train and severely hurt his knees on the fall, only to be recaptured. He was determined to get the precious intelligence back to Allied forces. On October 6, he squeezed through barbed wires and allowed German guards to see him so more prisoners could flee without much attention. They reached the mountains of southwest Germany, feasted on raw vegetables they found along the path, and sneaked past German sentries overlooking the Rhine River at night. Seven days later, Izac made it to Switzerland.

After World War I, he was awarded the Medal of Honor. He retired from naval service, became an elected congressmen, and raised beef cattle with his family in Bethesda, Maryland. Izac died in 1975.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.