This Controversial Cold War Program Trained Afghans To Wage an Information War Against the Soviets

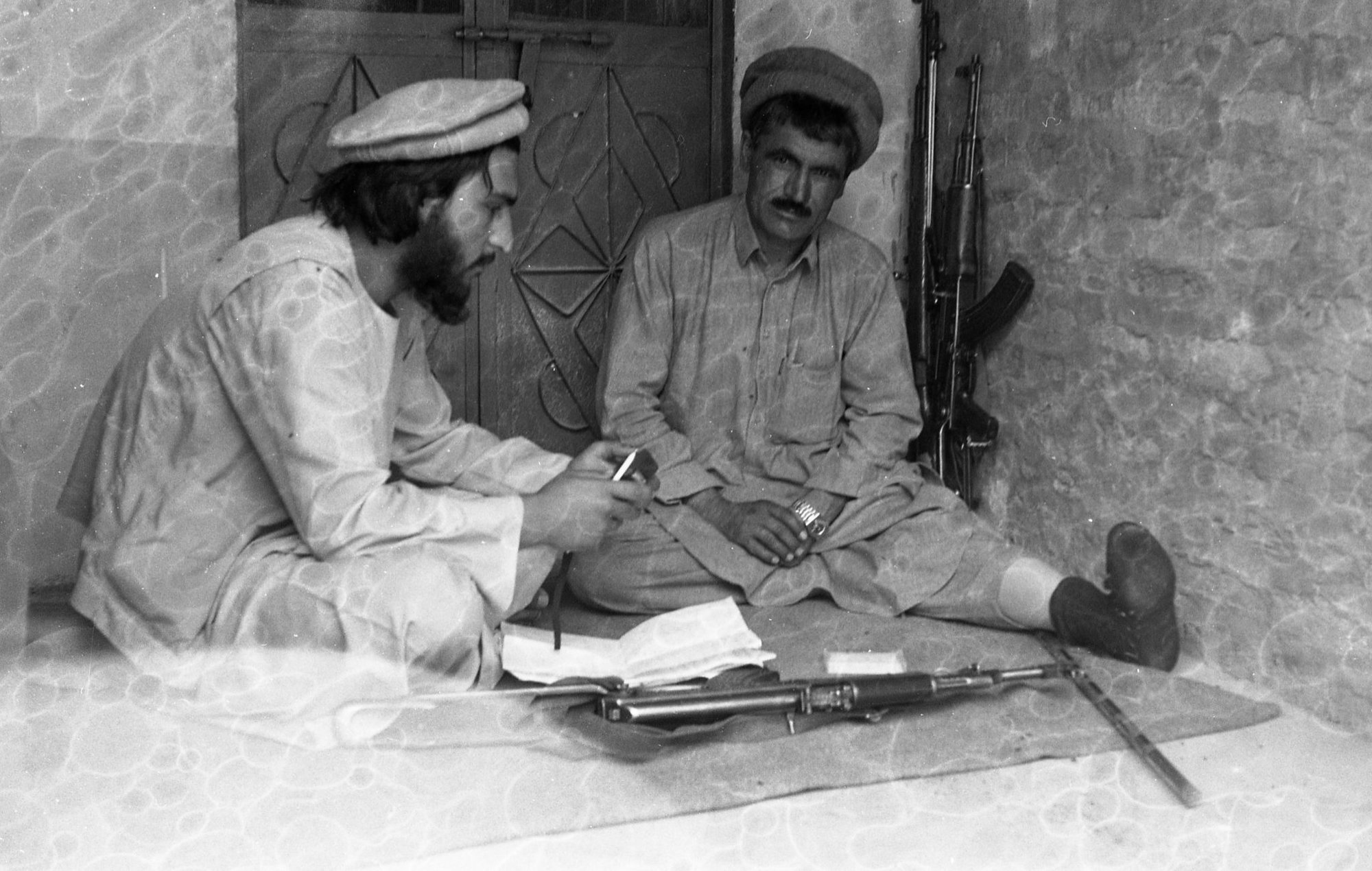

An Afghan Media Resource Center reporter interviewing a paralyzed Afghan mujahedeen fighter. Photo courtesy of the Afghan Media Resource Center.

In 1985, the US Congress approved a controversial $500,000 media program with the goal of teaching ordinary Afghans how to distribute reliable and accurate accounts of the Soviet-Afghan War. Led by the United States Information Agency, a group of media trainers under contract from Boston University founded the Afghan Media Resource Center, or AMRC, in 1987 in Peshawar, Pakistan.

The project’s genesis was a media blackout put in place by the Soviet-backed government in Kabul, the capital city of Afghanistan. The order put foreign journalists in harm’s way, legitimizing them as military targets.

The AMRC was championed by H. Joachim Maitre, the dean of the Boston University College of Communication. Maitre had wartime experience of his own. In 1953, he escaped East Berlin while traveling in an armored personnel carrier. He later made a documentary supporting rebel guerrillas in Nicaragua. Maitre even went to Angola to meet with Jonas Savimbi, the head of the country’s anti-communist insurgency.

In an effort to limit censorship in Afghanistan, Maitre promoted a free press through teaching journalism skills to Afghan refugees in Pakistan.

These skills were learned in six-week training sessions.

“Qualified Afghans were recruited from all major political parties, all major ethnic groups and all regions of Afghanistan, to receive professional training in print journalism, photo journalism and video news production,” according to the AMRC digital archive. “After the completion of their training, 3-person teams were dispatched on specific stories throughout Afghanistan’s 27 provinces, with 35mm cameras, video cameras, notebooks, and audio tape recorders.”

Ordinary Afghans weren’t the only ones to receive expert guidance. Acting director of the AMRC, Haji Said Daud, supervised the training of 70 “fighter-reporters” recruited from all of Afghanistan’s major rebel groups. During 70 missions, these fighter-reporters collected more than 200 hours of film and 6,000 photographs and slides.

Photo materials were distributed internationally through Sygma, a photography agency, and Agence France-Presse. Video was syndicated and broadcast by Visnews, which was later incorporated into Reuters. There were 150 broadcasters in 87 countries that assisted in the coverage.

Dating from 1987 to 1994 in Afghanistan, the AMRC provided the Library of Congress with a unique digital archive of 94,650 photographs, 1,200 hours of video, and 350 hours of audio recordings.

“That’s the largest collection of its kind anywhere in the world,” Mary-Jane Deeb, the former chief of the African and Middle Eastern Division at the Library of Congress, said during a 2016 presentation.

In 2012, the AMRC received a grant to digitize the entire AMRC archive. The Library of Congress completed the collection in 2016, along with metadata sheets in English, Dari, and Pashto. The entire AMRC collection is available to anyone interested in learning more about the history of Afghanistan.

Read Next: The Fall of Kabul: Is History Repeating Itself in Afghanistan?

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.