Air Force Worst at Sexual Assault Prosecution Standards, IG Finds

A Pentagon inspector general report found that none of the military services are in full compliance with training rules for prosecutors in sexual assault cases, with the Air Force farthest behind. US Army photo by Sgt. Melissa N. Lessard.

The military — and the Air Force in particular — is not living up to its promises in how it prosecutes sexual assault, a Pentagon report found.

The Pentagon Office of the Inspector General released a report Wednesday that found glaring deficiencies in how the Department of Defense investigates and prosecutes sexual assault cases. While the Pentagon has said it will assign a trained and certified special victim prosecutor to all sexual assault cases, every military service branch is failing to do so, the inspector general found.

The reasons, the report found, is a mix of too few trained prosecutors and an increase in the number of reported sexual assaults.

In 2013, Congress required each military service to create “a distinct, recognizable group of appropriately skilled professionals” to investigate and prosecute child abuse, serious domestic violence and sexual offenses while providing “support for the victims of such offenses.” The Department of Defense created special victim prosecutors in response.

But, the IG found, there are not enough to meet the need.

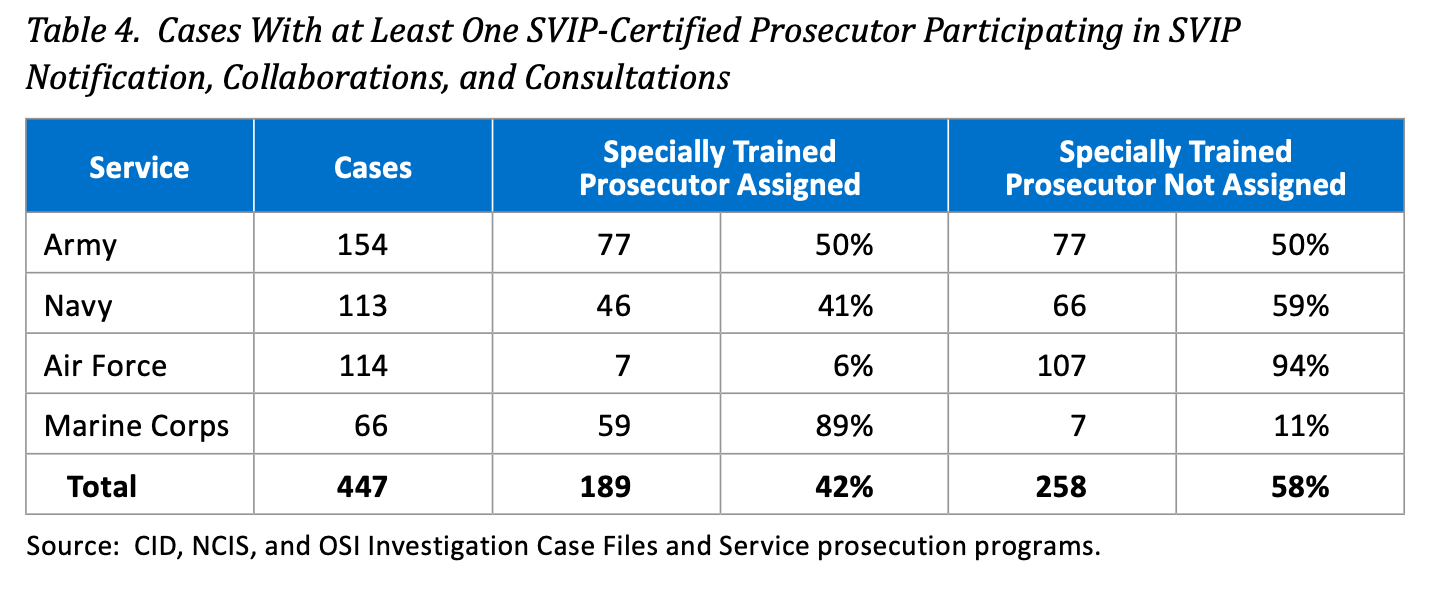

In 447 cases examined by the IG — about 1 in 7 of all reported cases — between June 2018 and May 2020, the Army did not assign specially trained prosecutors in 50% of cases, the Navy in 59%, and the Air Force in a whopping 94% of cases. The Marines assigned special prosecutors in almost 90% of their cases, though the report notes that the assigned prosecutors were not yet certified in many cases, but now are.

Retired Col. Don Christensen, president of Protect Our Defenders, told Coffee or Die Magazine that the findings, particularly those about the Air Force, should be unacceptable to Pentagon leaders.

“If I were Secretary [of Defense Lloyd] Austin, first thing I would have done is hauled the Judge Advocate General of the Air Force into my office and said, ‘Time for you to go,’” said Christensen.

The top lawyers for the Army, Navy, and Air Force all wrote responses to the IG’s findings, which were included in the final report. All agreed with the IG’s recommendations to do further internal review but disagreed with the report’s key finding on the specially trained prosecutors. The judge advocate general for the Navy pointed out that service could not certify its prosecutors until midway through the study period, while the top Army JAG said there had been a mix-up in which data was examined. When the Army ran its own numbers, it found only 8% of cases missing at least an assisting special victims prosecutor.

The Air Force flatly disagreed with the math of the IG’s findings.

“It is unclear how the DoD OIG calculated the Air Force’s rate of compliance,” wrote Maj. Gen. Charles Plummer, the service’s deputy judge advocate general.

Plummer noted that 16 cases examined by the IG, and counted against the Air Force’s compliance, were not under direct control of the Air Force but were run in civilian courts or otherwise outside Air Force jurisdiction. Of the others examined by the IG, Plummer said the Air Force provided properly trained lawyers in 22% of the cases, not the mere 6% that the IG found. Additionally, Plummer said, about half of the cases in question simply did not have paperwork detailed enough to determine if the lawyers involved were certified or not.

The IG report looked only at so-called unrestricted reports of sexual assault, which are cases in which the victim agreed to or asked for a formal investigation with law enforcement and their chain of command. “Restricted” reports allow victims to access health care, advocacy, and legal services but are not forwarded to law enforcement or commanders.

The report noted that since 2011, the yearly number of reports of sexual assault has more than doubled, while the number of lawyers available for potential assignment to those cases increased by just 5%. “A significant strain was placed on service prosecutorial resources,” due to this ratio, the report said.

Christensen thinks that’s not a good enough excuse. “It’s a priorities issue,” he said. “The JAG corps leadership could absolutely make sure that there’s a sufficient number of special victims prosecutors to do this. But they’ve decided it’s not important.”

One area in which the report found each service actually delivered was providing certified victim advocates. All services, the IG said, provided advocates 100% of the time and generally provided victims with information on available resources for assistance. But the numbers were not as good — and were, again, the worst in the Air Force — when it came to assigning certified lead investigators. The Army did not assign certified lead investigators in 9% of cases, the Navy did not in 16% of cases, and the Air Force did not in 66% of cases.

“We have fairly inexperienced investigators being advised by fairly inexperienced JAGs, and that’s where these cases are going sideways,” said Christensen.

All of the investigative offices told the OIG that they had not been provided with an increase in resources and manpower sufficient to the increased workload.

Military sexual assault has been in the spotlight from the very first days of the Biden administration. Austin called for an independent review commission on the subject within his first days in office.

And a controversial change to prosecution — removing investigation and prosecution of sexual misconduct from the chain of command — appears likely to be included in the National Defense Authorization Act for 2022.

“What that doesn’t address is that once the investigation starts, unless there’s an increase in special victims prosecutors, it’s going to be impossible for them to be there advising during the investigation,” Christensen said. “There’s no increase in special victims prosecutors that I’ve seen in legislation, no funding, no demand for more.”

The IG said Monday another report was underway looking at the law enforcement side of sexual assault, focusing on the Military Criminal Investigative Organizations compliance with Department of Defense requirements.

Read Next: SecDef Tells Pentagon To Prepare for New Sexual Assault System as Congress Debates

Maggie BenZvi is a contributing editor for Coffee or Die. She holds a bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of Chicago and a master’s degree in human rights from Columbia University, and has worked for the ACLU as well as the International Rescue Committee. She has also completed a summer journalism program at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism. In addition to her work at Coffee or Die, she’s a stay-at-home mom and, notably, does not drink coffee. Got a tip? Get in touch!

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.