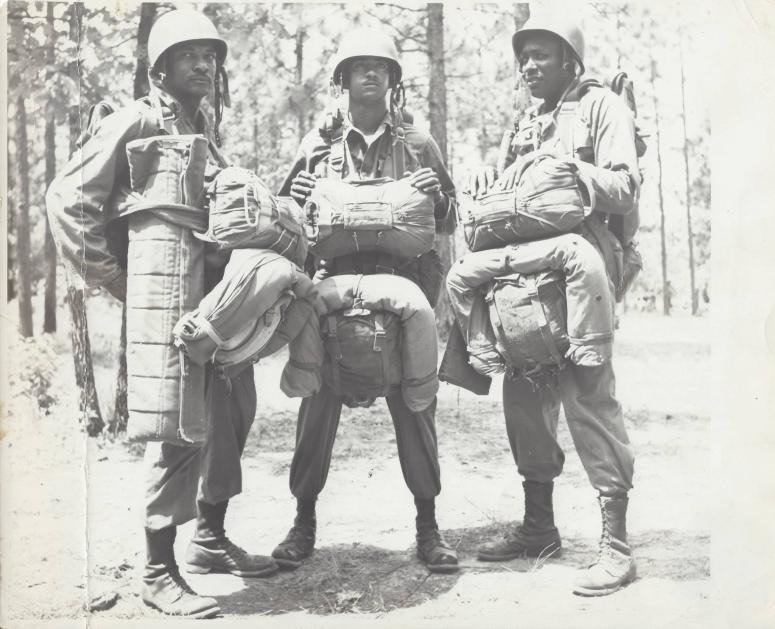

Members of the 2nd Ranger Company smiling for a team photo, courtesy of 2nd Airborne Ranger Company – Korea Facebook group.

About 20 guerrillas from North Korea — fighters consisting of both men and women dressed in civilian clothes — executed a hit-and-run raid against Americans in the Tong Yang vicinity in the first days of the new year in 1950. American units weren’t prepared to face this dynamic threat; they were untrained, ill-equipped, and unaware of the enemy’s speed and ferocity.

That changed when the 2nd Ranger Company, the first and only all-black Ranger Company in the history of the US Army — and a unit with a lifespan of just 10 months — arrived in-country with tactics they adapted from earlier engagements in the war, ready to take on the communist guerrillas and their unconventional tactics.

Their first firefight was led by 1st Lt. Warren E. Allen, an experienced prior-enlisted veteran of World War II in the Middle East. He set up a nighttime ambush and intercepted an enemy force, decimating them with suppressive fire from their Browning Assault Rifles (BARs) while fellow Rangers moved around the flank, employing hand grenades and submachine guns. His men eliminated all of the squirters (guerrillas running from the battlefield), earning the respect of their enemy and Allen’s fellow battlefield commanders alike.

And so, the legend of the 2nd Ranger Company was born.

Rebirth of Marauder Companies

The early battles of the Korean War exposed a gap in the US Army’s defense: Specialized teams from the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) were carrying out infiltration missions with deadly results. They attacked US and South Korean defensive positions and rear outposts, often at night and always with surgical precision. From the first surprise attack along the 38th Parallel on June 25, 1950, and over the following months, NKPA tactics surpassed and overwhelmed the Eighth Army, forcing their retreat into the pencil-neck peninsula known as the Pusan Perimeter.

The CIA reportedly admitted that they did not believe the North Koreans had the power to defeat the South nor that China would enter the war against the US. They were wrong on both accounts.

Gen. J. Lawton Collins, the chief of staff of the Army and World War II veteran, sent a memorandum citing the need for “Marauder Companies,” — an homage to the 5307th Composite Unit (known as “Merrill’s Marauders”), a deep-penetration unit used against the Japanese in the China-Burma-India theater of operations in World War II. On Sept. 6, 1950, the Marauder companies concept was merged into the existing heritage of Ranger companies at Fort Benning, Georgia. All members were required to be Airborne qualified.

The Chinese rolled him over; he didn’t flinch or make a sound as they stripped him of his wallet, watch, and valuables, then carried on.

The first three all-volunteer Ranger companies were white; the fourth company (which became 2nd Ranger Company) consisted of a segregated all-Black formation that merged with the 82nd Airborne Division’s 555th Parachute Infantry Regiment, more notably known as the “Triple Nickels” during World War II. The men of 2nd Ranger Company assumed the nickname “Buffalo Soldiers” in honor of historic Black regiments that served during the North American Indian Wars.

The instructors hand-selected to train the new recruits were battle-tested veterans from special operations units during World War II: 1st Special Service Force (The Devil’s Brigade), Merrill’s Marauders, Office of Strategic Services (OSS), and existing Ranger companies. The combined combat experience and unique skill sets set up these new Ranger companies for success. Each soldier trained in demolitions and carried all of their gear on their person: food, 60mm mortars, BARs, M1 carbine rifles, and other weapons.

Organization and Frozen Battles

The 2nd Ranger Company consisted of five officers and 134 enlisted men. They trained alongside other Ranger companies and earned their respect during the arduous conditions and training scenarios practicing first aid, patrolling, land navigation, demolitions, raids, ambushes, survival in vigorous climates, small boat operations, and small unit tactics.

The first engagement with the enemy was a success; the infantrymen of 2nd Ranger Company proved their effectiveness, however, soon they would discover that missions wouldn’t be so easy. After arriving in-country in December 1950, the Rangers received little support from the US Air Force and many men suffered.

In a 2014 interview with the US Army, Herculano Dias recalled how hellacious the combat was and how they endured bone-chilling temperatures: “A lot of guys were evacuated for frostbitten feet because the equipment we had was not sufficient.” Another Ranger, Richard Briscoe, who served alongside Dias, chimed in, “When we got off the plane, it was 20-below zero, and we had to ride in open trucks, with no canvas over (them).”

Evading Capture

Although the Rangers often had the element of surprise and assaulted when the moon illuminated the sky, they were sometimes misused as quick-reaction forces to aid other units. On Jan. 14, 1950, in a vicious firefight between the Chinese Communist Forces (CCF), 2nd Ranger Company was called off their target (where they killed an estimated 100 CCF soldiers) to support an infantry battalion nearby. The CCF broke through the defensive positions of the Americans in a nearby village after trudging through ankle-deep snow, mountainous terrain, and raw polar wind for five agonizing days and nights. The Chinese maneuvered and, in the confusion, divided the Ranger assault element.

Lt. Allen ordered his tired, wounded, and low-on-ammo forces to retreat, yet not all of them were able to bound back with the force. Cpl. Bill “Thin Man” Rhodes expelled his last magazine of M1 ammunition and had seconds to make a decision: feign death next to his slain Rangers or run for it. He belly-flopped onto the red-stained snow and slowed his breathing. The Chinese rolled him over; he didn’t flinch or make a sound as they stripped him of his wallet, watch, and valuables, then carried on.

They killed hundreds in a two-hour battle; miraculously, they didn’t lose a single man.

Thirty minutes later, Rhodes sneaked away, until he reached an open field. The worst place to be in any engagement, the “kill zone” was another great fear, but with time working against him in the blistering cold, he sprinted for it.

Bullets whistled past his nose, and he hit the dirt a second time as if he were killed. The Chinese took his boots and clothing, leaving him almost naked — but alive. Rhodes linked up with a Korean couple who provided him shelter, and by the third night of his evasion, he found an American patrol that brought him back to receive medical attention.

Munsen-Ni

On Good Friday — March 23, 1951 — 2nd and 4th Ranger Companies (legendary Easy Company officer Ronald Speirs was one of the few airborne soldiers to have combat jumps in both World War II and Korea) were part of Operation Tomahawk. The mission entailed 3,300 airborne infantrymen, including the smaller Ranger contingent, to conduct the first airborne assault of the largely contested North Korean position and disrupt supply routes to force a retreat. The Rangers were outfitted with small arms, 105mm howitzers, 60mm mortars, and support from small troop carriers and jeeps that parachuted in behind them. The Air Force softened the landing zone with strategic bombing runs.

Once they landed, they saw no serious opposition. The men patrolled 20 miles in the first day before linking up with tanks from the 24th Infantry Division and racing to control Hill 151. Intense fighting left dead North Korean soldiers at their feet — some from blows to the head, others from a well-placed bayonet.

Between March and May of 1951, outside the village of Chung-ni, an advance force element of 2nd Ranger Company captured and held Hill 581 during the Battle of the Soyang River. They defeated soldiers from the communist Chinese regime, the aggressive enemy they frequently clashed with during their engagements. The Rangers used everything they had and conducted a double envelopment supported by field artillery — a military tactic where the Rangers blocked escape from the rear. They killed hundreds in a two-hour battle; miraculously, they didn’t lose a single man. Seventeen Rangers were awarded the Purple Heart, and seven received awards for valor under fire.

Although the 2nd Ranger Company was awarded four campaign streamers, nine Silver Stars, 12 Bronze Stars with Valor, and more than 100 Purple Hearts during the course of their service in the Korean War, the unit was disbanded on Aug. 1, 1951. Of the 110 members, none were ever taken as a prisoner of war, a testament to the fighting spirit of a unit that helped change US military policies during the height of the civil rights movement.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.