Before Stephen King, America’s ‘King of Horror’ Was a Civil War Vet With TBI

“The Complete Short Stories of Ambrose Bierce.” Photo by Mac Caltrider/Coffee or Die Magazine.

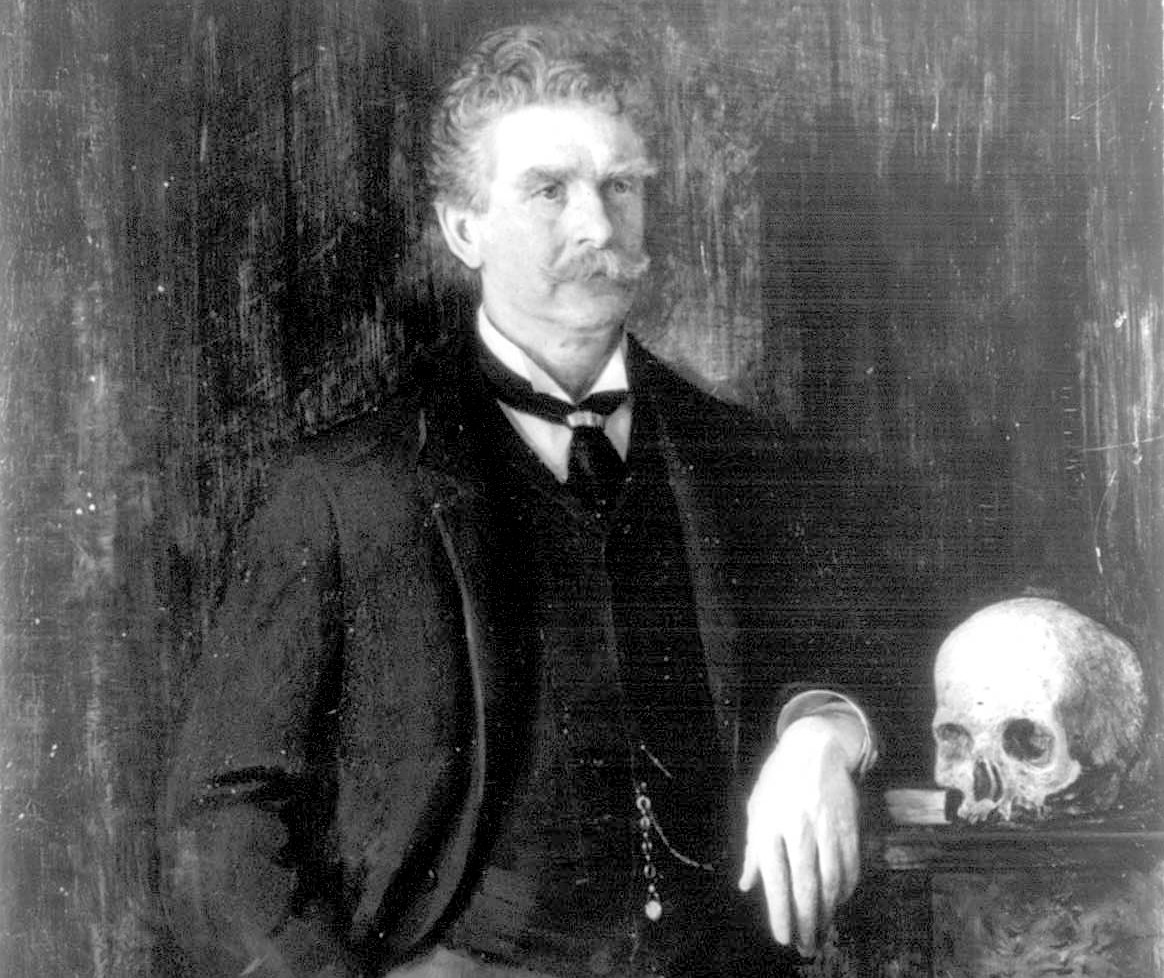

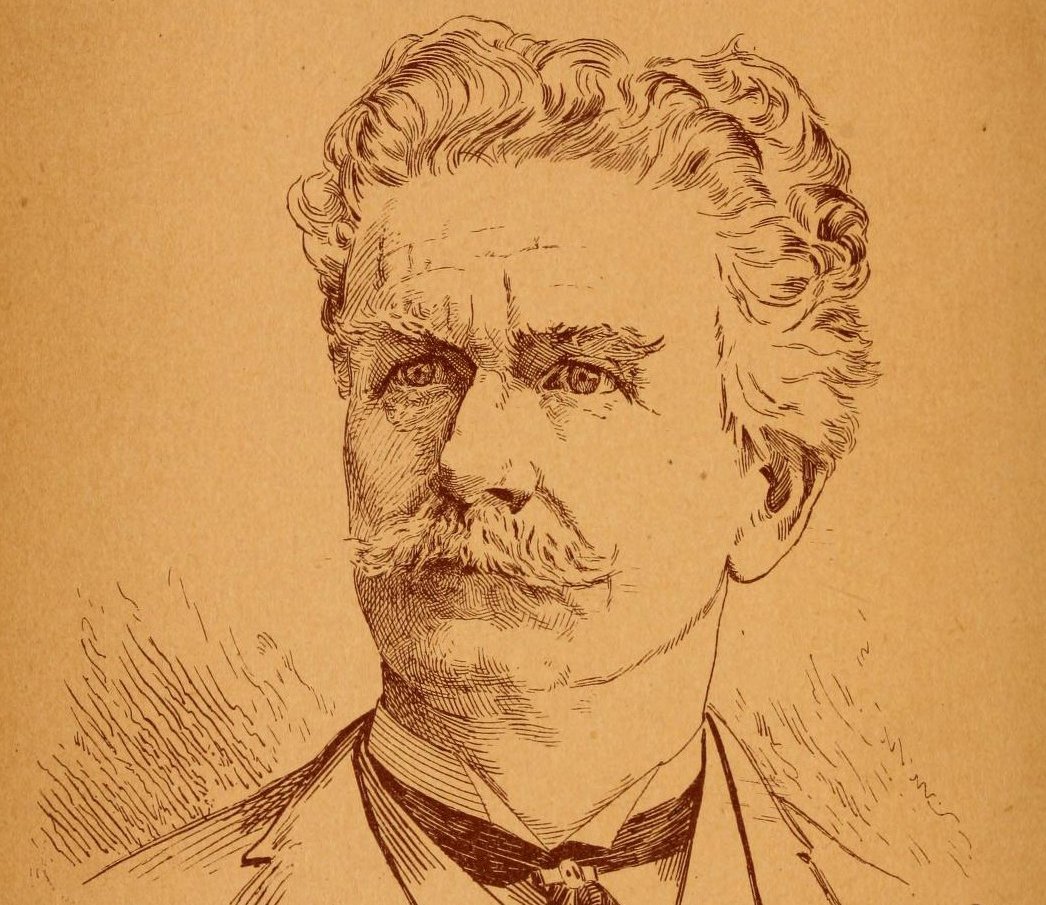

Seldom do literary giants lead lives as interesting as their stories. Hemingway may have personified the hyper-masculine lifestyle of bull-fighting and binge drinking he often wrote about, and Edgar Allan Poe’s untimely death might be equally as mysterious as the morbid tales he’s famous for, but few writers have upstaged their own characters quite like Ambrose Bierce did.

From tales challenging the notion that war is a beautiful and glorious thing to horror stories written to shock the reader, Bierce drew upon his lived experiences as a soldier during the Civil War to add an undeniable level of realism to his writing.

His Civil War Stories, considered by Ernest Hopkins to be the “greatest anti-war document in American literature,” focuses on the absurdity of war and the tragedy of combat. In “Bivouac of the Dead,” Bierce openly criticized political leaders rather than his dead Confederate enemies.

“They were honest and courageous foemen, having little in common with the political madmen who persuaded them to their doom and the literary bearers of false witness in the aftertime,” the piece reads.

Like Stephen Crane’s work, Bierce’s descriptions of combat ring uncomfortably true, but unlike the author of The Red Badge of Courage, Bierce endured the horrors of war before he ever wrote about them.

He enlisted in 1861, following Lincoln’s first nationwide call for volunteers, and was present during the first organized land battle of the Civil War.

One month later, Bierce was under fire again during the Battle of Rich Mountain. During the fighting, he exposed himself to enemy fire to rescue a wounded comrade. His courage continued throughout the war, ultimately leading to a battlefield commission.

Bierce spent much of the war in combat, serving in notably bloody campaigns such as Shiloh, Chickamauga, Murfreesboro, Chattanooga, and Sherman’s infamous March to the Sea. But it was at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain that he came closest to death, which became a theme that permeated nearly all of his later writing.

During the fierce combat, an enemy bullet struck Bierce in the head, miraculously glancing off his skull without killing him. He survived the gunshot but was left with a traumatic brain injury that plagued him with fainting spells and mood disorders for the rest of his life.

His being witness to so much destruction during the war and his own personal brush with death left a visible impact on his writing, most obviously in his horror short stories.

Horror was just beginning to grow into a respected genre in the 1800s. The Gothic-horror writers of the time developed atmospheric horror, which the “shadow-maker” (as H. P. Lovecraft called Bierce) expanded on by adding supernatural phenomena and trick endings.

In “The Damned Thing,” Bierce creates an invisible beast that psychologically torments and ultimately kills a terrified hunter. His description of the imaginary attack reads as if he’s describing a true event.

“At the same instant I was thrown violently to the ground by the impact of something unseen in the smoke — some soft, heavy substance that seemed thrown against me with great force,” Bierce wrote, describing what could be transplanted into a war story as an accurate description of being hit with an explosive concussion.

He continues, “At a distance of less than thirty yards was my friend, […] his head thrown back at a frightful angle, hatless, his long hair in disorder and his whole body in violent movement. […] His right arm was lifted and seemed to lack the hand.” This is how Bierce describes a man dying at the claws of an invisible monster, yet the image could easily be drawn from a battlefield scene of a man hit with artillery.

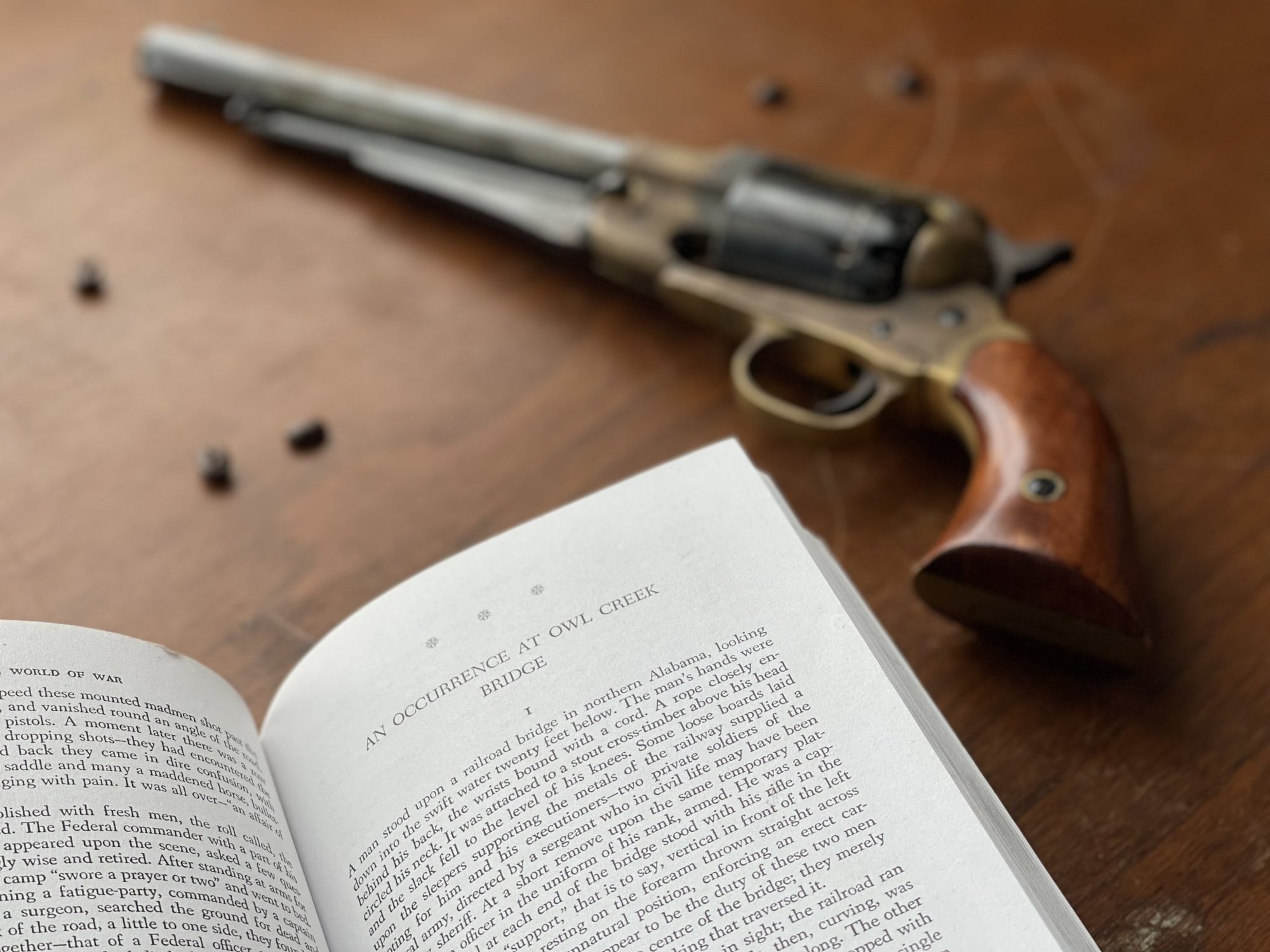

At times, Bierce blurred the lines between the horror and war genres. His most famous story, “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” is lauded for its signature surprise ending, but the mixing of horror and war is really what makes the story worthy of Kurt Vonnegut’s praising it as the greatest American short story.

The story describes the hanging of Peyton Farquhar, a captured soldier, as told by the doomed man. With the noose around his neck, and moments left to live, Farquhar manages to slip the rope and escape. As Farquhar swims ashore, under fire from his executioners, Bierce describes the strange, adrenaline-induced sensation of hyperawareness.

“He looked at the forest on the bank of the stream, saw the individual trees, the leaves and the veining of each leaf — he saw the very insects upon them: the locusts, the brilliant-bodied flies, the gray spiders stretching their webs from twig to twig. He noted the prismatic colors in all the dewdrops upon a million blades of grass.”

Bierce’s depiction of sharpened senses is a more realistic description of what it’s like to be under fire than are the glorious memoirs of generals and large troop movements that are typically associated with literature of the Civil War. In the same story, Bierce combines detailed realism with elements of supernatural horror.

Soon after Farquhar evades the noose and the gunfire, he escapes into the forest. Bierce describes the trees as “black bodies” and stars as forming strange constellations of “malign significance.” He continues to build an atmosphere where things aren’t quite right by having Farquhar hear “whispers in an unknown tongue” coming from the shadows. The strangeness of his “war story” alludes to the famously shocking conclusion, but more importantly, it keeps the story from falling neatly into a single genre.

Just as Bierce’s military service lent to the eerie realism of his short stories, his death lived up to the strange tales he’s remembered for. In 1913, at 71 years old, Bierce brazenly ventured into Juarez during the Mexican Revolution. He joined Pancho Villa’s army as a noncombatant and vanished into eternity.

Theories surround the nature of his disappearance, ranging from tales of pneumonia to oral legends of an execution by firing squad. In a final letter to his friend Nellie Sickler, he wrote, “Naturally, it is possible — even probable — that I shall not return. These be ‘strange countries,’ in which things happen; that is why I am going.”

Even at the end of his life, Bierce valued experiencing life’s adventures over writing from a place of speculation.

Read Next: How the Civil War Created Photojournalism

Mac Caltrider is a senior staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. He served in the US Marine Corps and is a former police officer. Caltrider earned his bachelor’s degree in history and now reads anything he can get his hands on. He is also the creator of Pipes & Pages, a site intended to increase readership among enlisted troops. Caltrider spends most of his time reading, writing, and waging a one-man war against premature hair loss.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.