What the United States of America and Her Flag Mean to Many Nations Around the World

An anti-government protester carries an American flag during a demonstration at Causeway Bay district in Hong Kong, China September 29, 2019. Photo by Tyrone Siu/Reuters.

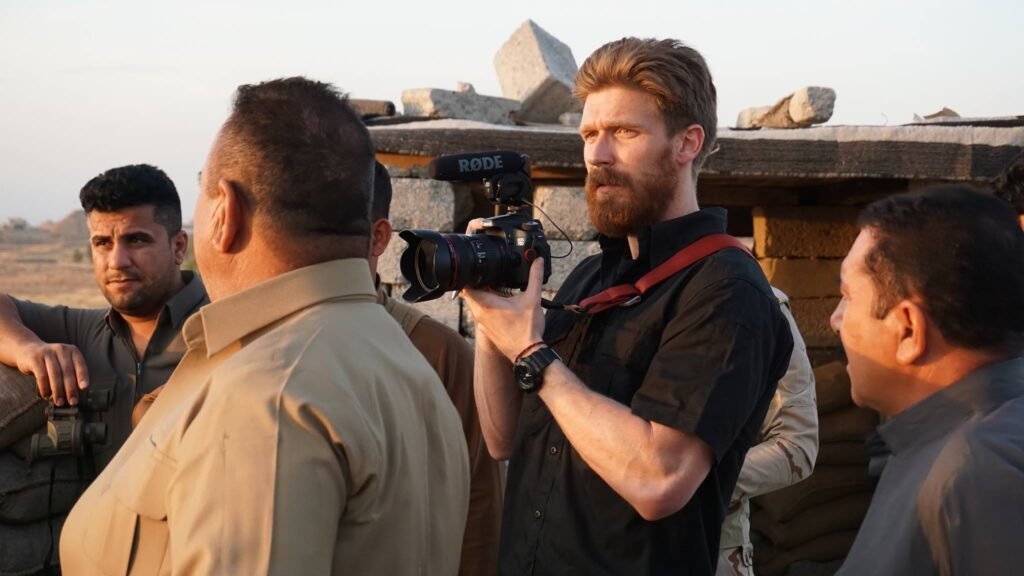

Near sunset one evening in the summer of 2016, I was on the rooftop of a Kurdish Peshmerga fort in the front-line town of Gwer, just south of Mosul, Iraq. I stood behind a sandbag berm beside Kurdish General Omar Hama Ali Farag, and we watched through binoculars as ISIS fighters scurried between their positions a mile away across a dry riverbed.

On the other side of no man’s land, the terrorists looked like distant rats with their all-black garb and frantic movements. There they were. The foot soldiers of the terrorist army responsible for so much death and destruction. Disciples of the twisted cause that had brutally killed the journalist James Foley, who was my friend.

Small in stature with a trimmed salt-and-pepper mustache, Farag wore a black-and-white turban and the traditional Kurdish sal u sepik uniform. The general paced back and forth among his men with his hands clasped behind his back. At times he had a fatherly air. In other moments, Farag’s eyes narrowed and his face transformed into a remorseless expression I have only seen among soldiers at war.

Then jet noise snarled overhead. I looked up and saw the arrowhead shape of two F-16s scorching across the clear blue sky.

Farag, like many older Peshmerga soldiers, had survived Saddam Hussein’s al-Anfal genocide in the late 1980s. More than 180,000 Kurds died in those attacks — many due to chemical weapons dropped from Saddam’s fighter planes. The sounds of jet engines had thereafter stirred terror among the Kurds who remembered al-Anfal. Years later, however, during the war against ISIS, the growl of American warplanes inspired an altogether different feeling.

“That’s the sound of God,” Farag told me.

As the U.S. fighter jets roared above, the Kurds pointed to the sky, laughing and smiling. Empowered, a few soldiers fired potshots toward the enemy lines.

“Now the sound of the planes makes me happy,” Farag said. “I can’t explain how important the U.S. planes are for us. If we can’t hear the sound of the planes, we can’t stay here and fight.”

The sun was low, and the sky was clear. The jets were clearly visible. Then, the thunder of bombs. Puffs of tan dust and smoke rose where the enemy had once been but no longer was.

A flock of startled birds took flight. I felt satisfied. I thought back to my previous profession — when I was a U.S. Air Force special operations pilot in Iraq and Afghanistan. I knew what war looked like from up there. Now, I knew what it looked like from ground level, among those brave fighters who depend on U.S. airpower to survive.

“Allahu akhbar,” Farag said.

“Allahu akhbar,” I agreed.

As the sun dipped below the distant, ancient hills, we stood together, listened to the sound of God, and watched our enemies die.

I spent a good chunk of my life in the military, and I paid my dues in Iraq and Afghanistan like the rest of my generation in the U.S. armed forces. But it wasn’t until I left the military and became a journalist that I ever truly understood what I’d spent my youth fighting for.

Sure, I knew that my service was one tiny part of the bigger effort of keeping the homeland safe. But maintaining a dominant military with a global presence is not just about America’s national defense, or even international stability. Our military is also the torchbearer for our country’s values. And our nation’s flag remains a beacon of hope for people fighting for their freedom around the world.

As a war correspondent, I’ve had the privilege of witnessing these truths firsthand.

In February 2015, I joined a U.S. Army Stryker convoy as it traveled 1,100 miles from Estonia, down through Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and into the Czech Republic. The convoy was called Operation Dragoon Ride; it was meant to show the United States’ resolve to defend NATO’s eastern members from Russian aggression.

Along the way, thousands of people lined the roadside waving U.S. flags. Fathers had children on their shoulders. Young women blew kisses to the U.S. troops. At each stop, no matter how small the village, people gathered to meet the soldiers and get selfies with them.

I wish you could have seen it; you would have been proud to be an American. I certainly was.

In February 2019, I visited Kosovo for its 11th Independence Day. A military parade marked the occasion in the capital city of Pristina, and observers lined the streets waving Kosovar, Albanian, and U.S. flags.

Before the parade, I had lunch at a café on Saint Mother Teresa Boulevard, Pristina’s main thoroughfare. When I asked for the check the waiter simply smiled and said, “It’s on the house.”

I asked why.

The waiter, whose name was Fadil Azemi, replied: “Your country saved mine. The least I can do is buy you lunch.”

The people of Kosovo are proud of their country’s hard-earned independence. And they’re particularly grateful for the U.S.-led NATO air war in 1999, which reversed a Serbian ethnic cleansing campaign and saved their country from catastrophe. In Pristina’s city center, a statue of Bill Clinton stands beside a boulevard named in the former president’s honor. There’s also a “George Bush Boulevard.”

“We fought for our freedom and our independence, and we would have never won the war on our own—the U.S. is the savior of the people of Kosovo,” President Hashim Thaçi of Kosovo told me during an interview in Pristina.

Under Russian artillery fire in the trenches in eastern Ukraine, I’ve seen Ukrainian soldiers with American flags on their uniforms. They told me the flag symbolizes the freedom they’re fighting for. In the trenches in the front-line town of Pisky, I met one Ukrainian soldier who wore a Ronald Reagan Presidential Library T-shirt. When asked why, he said: “Because Reagan won the Cold War, and it would piss Putin off.”

At the front-line village of Krymske in 2015, Ukrainian troops renamed a street “John McCain Street.” To make it official, the troops taped a sheet of paper bearing McCain’s picture to a power pole.

In the front-line town of Shyrokyne in 2015, Ukrainian soldiers raised an American flag over their entrenched positions. The flag, once raised, invited the predictable response from the Russian side in the form of a few lobbed mortar rounds.

A Ukrainian National Guard soldier named Ivan Kharkiv made a video of the event.

“No Russia, no Putin, only Coca-Cola, only Barack Obama. U.S.A., all the way,” Kharkiv says in the video; the sounds of gunfire and artillery are audible in the background.

On Thanksgiving 2016, I visited the Ukrainian army’s 92nd Mechanized Brigade, which was dug in just outside the front-line town of Marinka. I went to the Ukrainian war zone that time with my younger brother, Drew, who is also an Air Force veteran and served in Afghanistan.

That night, Drew and I stood atop the Ukrainian fort and watched with both horror and awe as rockets and tracers cut across the blackened sky. The sounds of explosions rolled in seconds later, out of sync with the far-off flashes of light. This storm of steel was the nightly rhythm of Europe’s only ongoing land war.

It was a “regular night,” the Ukrainian soldiers told us.

Later, Drew and I shared a meal and a succession of toasts with our Ukrainian hosts. At first, the Ukrainians looked on us with suspicion. After all, we were foreigners in a war that wasn’t our own. Yet, as the alcohol caught up and the cultural and language barriers came down, the Ukrainians had a lot of questions about Afghanistan for my brother and me. Most of their fathers had fought in Afghanistan as Red Army soldiers in the 1980s, and the fact that Drew and I had both served there bought us instant credibility.

Soon we were as comfortable together as if we were all soldiers from the same country. And, even though we served under different flags, we’d all chosen to fight for similar reasons. The words “freedom” and “democracy” came up a lot that night — and so did the word “friend.”

“More than ammunition, we need to know we’re not alone,” a Ukrainian soldier named Andriy told us.

In the summer of 2015, I embedded with the Ukrainian regular army for eight days in the front-line town of Pisky, just outside the Donetsk airport.

It was an active time with near-constant artillery and mortar fire. The town was abandoned and had been destroyed by the fighting. Most buildings had partially caved-in roofs from artillery hits. Bullet and shrapnel holes pockmarked nearly every vertical surface. Artillery blasts had stripped the branches from many trees. In places, the earth was cratered like the moon. And I didn’t see one window that wasn’t shattered.

This was a long-distance war in which the two sides hardly ever saw each other except through binoculars or a drone feed. Artillery was lobbed back and forth every day. Sometimes the tanks would come out, too, maneuvering to different positions to fire off a few rounds before returning to their hiding places. The sound of tank treads clanking was never good.

The fighting was ongoing and practically nonstop, creating a constant background din of explosions and gunshots. At night you could hear the buzz of Russian drones orbiting overhead — the Ukrainian soldiers call them “sputniks.”

Like most of the units stationed in Pisky, the soldiers with whom I embedded lived in the basement of an abandoned house. The only safe refuge from the artillery and snipers was to be underground. Russian-separatist patrols would slip through the lines at night to start firefights. Sometimes they tried to kidnap prisoners. So the Ukrainian soldiers slept with their Kalashnikovs cradled in their arms, always ready for a fight.

Psychologically, it was a tough war. The hardest part for me was that you could never escape the danger. You could die just as easily walking to the toilet or while taking a shower as you could out on patrol or in the trenches. You just never knew when the artillery was going to start or when a sniper had you in his sights.

Unlike what I experienced as a pilot in Iraq and Afghanistan, there was no safe place in the Ukrainian war zone. No walled-in fortress to which we could retreat between missions to grab a Subway sandwich. Every second, in the back of your mind, you worried about dying. And usually your chances of survival just depended on good luck and not being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Some Ukrainian soldiers learned to simply laugh at the danger and treat the war like a sport. Others grew quiet and gloomy, imagining at every moment how they could die. And then there were those exceptional warriors who were able to see the war for the tragedy it truly was and went on fighting anyway.

“It’s impossible not to be motivated when the enemy has attacked the motherland,” Ukrainian volunteer soldier Vasiliy Ivaskiv, then 53, said as he cooked me breakfast in that basement artillery shelter.

A former coal miner from the western Ukrainian town of Ivano-Frankivsk, Ivaskiv volunteered to serve in the Ukrainian army after he had made a few trips to deliver supplies to front-line troops in the early days of the war.

“I saw those young men fighting and dying for Ukraine, and I knew I had to fight too,” he told me, proudly adding that his father had fought the Nazis in World War II.

When he left for war, Ivaskiv said he had to step over his wife, who was in a sobbing heap in the doorway. She begged him not to go.

“There was nothing she could do to stop me,” he said. He scooped some scrambled eggs onto my plate, then paused and stood before me with the pan in his hand for a moment before he added, “I had to go. It was my duty.”

Compact and muscular, the then-53-year-old exuded energy, leading day-long patrols with men less than half his age. A father figure, Ivaskiv always seemed to be fixing something and usually did the cooking for the younger troops.

Ivaskiv had grown up in the Soviet Union and once considered America to be his enemy. But when I met him on the front lines in 2015, he practically beamed with pride that an American journalist, and a U.S. military veteran to boot, was willing to risk his life to tell the truth about the war in Ukraine. He called me “America” and had a habit of using his body to shield me from sniper fire. I told him he didn’t have to do that, but Ivaskiv only shook his head dismissively, pointed back and forth between our two chests, and said a single word:

“Friends.”

While I was in Pisky, I befriended a young soldier named Daniel Kasyanenko. He was only 19, but Daniel had an amazing ability to put the war in perspective, and he understood the toll that combat was taking on his young soul.

“I want to go home, just for a bit,” he told me. “Just for a week.”

“Do you get tired of the battles?” I asked.

“Physically, no. Morale, I’m tired. Very tired.”

Daniel and I spent nights around the basement’s dinner table as the artillery thundered and gunfire crackled outside. We traded stories of home, of family, of my time as an Air Force pilot and his time on the front lines. I played the undeserved role of mentor to a younger man who knew more about courage and sacrifice than I ever will. For his part, Daniel had a lot of questions about life in America.

“What is Thanksgiving?” he asked, and: “What are the beaches like in Miami? Do they really wear cowboy hats in Texas?”

Daniel’s dream, he told me, was to go to America. That’s why he studied English so diligently. He liked American rock and rap music and knew the Hollywood action movies by heart, frequently dropping quotes by Schwarzenegger, Willis, and Stallone.

“Get to the chopper,” Daniel would often say in a German accent before going on patrol, quoting Schwarzenegger’s well-known line from the movie “Predator.”

Yet, unlike the action-movie actors he could quote, Daniel truly knew about war. And he knew it wasn’t like in the movies. Daniel, more than many soldiers twice his age, recognized the things he would have to carry for the rest of his life because of what he had already seen and done at the outset of manhood.

Daniel knew war was not black and white. And that is, I believe, why the things Daniel had done and seen in war haunted him so much. He saw his enemies as humans, yet he never failed to pull the trigger when he had to. Consequently, the things he had seen and done in war haunted him. Daniel told me that war had “ruined” him and his “understanding of life.” He said it would have been better if he had gone to war as an old man.

“I want to get out of these battles,” he told me. “I want to forget it. But I can’t.”

When I left Pisky, Daniel and I pledged to stay in touch. We even talked about the possibility of him coming to America one day. But shortly after I got back to Kyiv, I received a somewhat disjointed text message from Daniel. He’d been injured by a mortar, he told me, and had what the Ukrainian medics called a “brain contusion” — which probably meant he had a concussion, or, more likely, a traumatic brain injury.

Daniel’s commanders gave him a few weeks leave to go back to his hometown of Zaporizhia, only a three-hour car ride from the front lines. He spent several weeks at home, living with his parents, Marina and Konstantin. It was a tough time for Daniel’s parents as they tried, over and over, to convince their son, their only child, that he didn’t have to go back to war.

And the truth is, he didn’t.

You see, when Russia invaded Ukraine in the summer of 2014, Daniel, like so many young men and women in Ukraine at that time, simply headed for the front lines and joined the ranks of a civilian volunteer battalion.

Many of these volunteer soldiers, like Daniel, had been protesters in Ukraine’s 2014, pro-democratic “Revolution of Dignity.” And, like Daniel, few of them had any military experience before they faced Russian tanks and artillery. These volunteers learned how to be soldiers while on the front lines, under fire, and with no formal training. They jokingly called it “natural selection” training.

It was a grassroots war effort. An example of a country that didn’t need to be persuaded into going to war by propaganda. Ukrainians simply fought to defend their homeland when they had to.

Daniel was only 19 when he went to war. He went straight from living under his parents’ roof to living under Russian artillery and sniper fire. There was no chance for him to become a man before he became a soldier.

Marina later told me that while Daniel was home on convalescent leave, she would watch her son sleeping and remark on how much he’d changed in the few months he’d been away.

“He went to war as a boy and came back as a wise old man,” she said.

On the day he left to go back to war, Marina begged Daniel to stay.

“Mom, I have to go back,” Daniel answered. “I have to go back to my friends. It’s my duty.”

He did.

And two weeks later, a mortar killed Daniel during a battle in Pisky.

Years later, my wife and I traveled to Zaporizhia to meet Daniel’s parents. It was a special time, and we were overwhelmed by their hospitality.

I knew my visit meant a lot to Marina and Konstantin. But the truth is, there’s no way for a parent to ever recover from losing a child. The Kasyanenkos’ sorrow was undiminishable, no matter how many nice things I had to say about their son. The pain of losing Daniel was, and will forever be, the bedrock to both their lives. The smiles, the jokes, the good times. That is all a thin veneer over the piled-on strata of sadness that reaches straight to the center of their souls.

“It was always Daniel’s dream to be an American soldier,” Marina told me. “And he was so proud to have you as a friend.”

The first thing I did when I arrived in Ukraine in the summer of 2014 was visit the Maidan, Kyiv’s central square and the epicenter of the 2014 revolution. At that time, the Maidan’s stone floor was still scarred by the piles of tires protesters had burnt to create a smokescreen from the pro-Russian regime’s snipers.

Then I walked to the top of Institutskaya Street, as it was still called, and saw the place where the snipers had gunned down dozens of protesters the preceding February. There, bullet holes pockmarked the sidewalks and street signs — as they still do today.

On that day in 2014, beds of flowers and candles covered the area, as did rows of framed photographs of the more than 100 protesters who had been killed during the revolution — the “heavenly hundred,” as they’re now known in Ukraine. The faces of the fallen included the young and old, men and women. As I walked around, trying to appreciate what had happened there a few months earlier, I heard a voice speaking in English, which stood out from the rest.

“Freedom isn’t free,” that voice said.

Freedom isn’t free.

I was still thinking about those words in October 2015 when I met Tsering Tunduk, who was then 66 years old, at his remote lakeside home in the Himalayas.

Tunduk lived with his wife in a small cluster of nine homes called Man on the Indian side of Pangong-Tso, a 53-mile-long lake that lies at an altitude of 13,500 feet on the Himalayan border between India and Tibet.

The only settlements along the lakeshore were a small collection of tents and shacks at the north end called Spangmik, and some seasonal tents and a half-dozen primitive homes farther east at Man. Both were on the Indian side of the lake. Otherwise, the place was pure wilderness — the unmerciful end of the world.

It was a long trip to get to Pangong-Tso, and once I got there I rented a room for the night at Tunduk’s home.

With his wife, Ganyen Tsultime, Tunduk led a spartan life in Man. The couple stockpiled food, fuel, and other supplies for the winter in case snow closed the roads. Dried saucers of yak and cow dung layered the top of their roof. That dung was used to fuel the stove, as there were no trees for firewood. The old couple slept, ate, and passed time in the main room, where the stove provided warmth.

Tunduk’s clothes were worn and his face was darkly tanned and weathered into a rough, leather-like hide by a lifetime in the high-altitude sun. He also wore a necklace with an intricately woven amulet, which he handled like a priceless work of art. It was a gift from the Dalai Lama, he explained with pride.

Short but solidly built, Tunduk stood straight and moved purposefully. His 66-year-old body and features had been hardened by a difficult life, not broken by it. The old man smiled constantly and used his hands a lot as he spoke, placing a hand over his heart to show sincerity, and a hand on your shoulder or knee for rapport. He pulled on his wispy Fu Manchu mustache when speaking seriously, as he did when he said in his halting, staccato English, “I came here because it reminds me of Tibet. It’s a very hard life here. We live like nomads, as my parents did.”

As he prepared dinner, I noticed a faded old picture of Tunduk as a young man. In it, he wore U.S. army fatigues and stood beside a much taller, Caucasian soldier in the same type of uniform.

Curious, I asked Tunduk about the photo.

“That was my friend from the CIA,” he told me as he peeled potatoes. He nonchalantly added, “When I was a soldier in the Indian Army.”

Naturally, I was intrigued.

By the warmth of his yak-dung-fueled stove, we talked late into the night. Tunduk told me all about his early life. He talked about China’s 1959 invasion of Tibet, and how he’d watched Chinese soldiers execute his parents in a public “thamzing,” or “struggle session.” And he explained how the Chinese soldiers had painted a bull’s-eye on his mother’s chest and used her for target practice. They kept shooting her long after she was dead, he told me.

Tunduk remembered looking into the faces of the Chinese soldiers and seeing nothing. Neither pleasure nor pain. It was as if they had no emotions, he said. A lifetime later, when the old man closed his eyes to sleep he was still haunted by images of his dead parents. As he described their murder, Tunduk’s usual smile was replaced by something cold and expressionless. His mind had returned to a time and place that no words, not even from one’s native tongue, have the power to faithfully recreate.

“I wanted revenge,” Tunduk said. “I wanted to kill them all.”

His face, turned to me then, was empty. I saw the unmistakable look of a soldier in the old man’s eyes.

Orphaned and angry, Tunduk was taken in by refugees and escaped across the Himalayas into India. Years later, he joined a special Indian mountain warfare unit called Establishment 22. The original purpose of this CIA-backed, all-Tibetan outfit was to use Tibetans’ genetic ability to perform at high altitude to wage a guerrilla war against China in the Himalayas.

However, Tunduk never saw combat against Chinese troops, as he’d wanted. Instead, he fought against Pakistani forces in the Himalayas.

“The army gave me a good life,” he said. “But—sometimes, I became frustrated when I had to fight in other peoples’ wars. Our aim was to fight with China. Pakistan is not my enemy. China killed my parents and captured my country. China is my enemy.”

Tunduk, a devout Buddhist, believed he was a sinner for what he had done as a soldier. He killed in combat and was deeply ashamed of it. To atone, he lived a quiet life at the edge of the world on Pangong-Tso lake. It was a place that reminded him of Tibet, and where, as an old man, he could live the peaceful life he never knew as a boy.

Only the lake separated Tunduk’s home from Tibet. Tantalizingly close, but Tunduk had not set foot in his homeland since 1959. Still, he never gave up hope that one day, maybe, he’d get to go home again.

At dawn on the morning of my departure, I found Tunduk outside his home standing on the lakeshore. He faced toward Tibet and thumbed his prayer beads while chanting the Buddhist mantra, “om mani padme hum.” His mouth moved almost imperceptibly as he repeated the words. The light of the rising sun grew slowly from where it would rise, behind the mountains of Tibet on the opposite shore.

The old man’s eyes were fixed across the burning blue water toward his homeland, from which he had been exiled for more than half a century. The impossibly far away seemed close enough to touch in the thin air. Right there, just across the water, a life and a world that no longer existed. A yesterday that seemed so close but was gone forever.

“Every being has a birthplace, a place where they dream of going back to,” Tunduk told me. “My identity is Tibetan. Until death we will want our country back.”

Yes, it’s true that freedom isn’t free. And the price of freedom is usually set by those who wish to destroy it. Yet, I’ve met so many people who believe freedom is worth fighting for. No matter its cost.

Like Oxana Chornaya, a 37-year-old university professor who put her life on hold when the Ukraine war began so she could deliver supplies to Ukrainian troops on the front lines. She wore body armor over her floral sundresses as she weaved an old, fully loaded minivan through artillery fire.

“Sometimes I’m so afraid I can’t take my hands off the steering wheel,” Chornaya said when I interviewed her in 2014. “I get so scared. My knuckles are white, and I can’t breathe. But I have to do this.”

I remember Lhasang Tsering, a former Tibetan guerrilla fighter who served in Nepal’s remote Mustang region. He turned down an opportunity to attend medical school at Johns Hopkins University to join the Tibetan resistance — a decision for which the Dalai Lama personally scolded him.

“In my view, achieving freedom comes first,” the then-68-year-old said proudly when I interviewed him in 2015. “I decided then that I was going to dedicate my life to the freedom struggle. And I am still ready to die for independence.”

Freedom isn’t free.

Those words echoed in my mind as I stood on that rooftop outside Mosul alongside my Kurdish friends and listened to the “sound of God.” Over dinner later that night, Farag, the peshmerga general, said to me: “Before, we had no friends but the mountains.”

He smiled and put a hand on my shoulder. “Now we have America, too.”

And today, from afar, I’ve watched with pride as protesters in Hong Kong frequently wave the Stars and Stripes as they’ve bravely resisted the recent, unprecedented threats on their freedoms by Communist China.

Hong Kong’s protests began in June 2019 over a new bill allowing the extradition of the special autonomous-city’s citizens to mainland China. In November, Washington passed a new law — the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act — that supports the Hong Hong protesters and the city’s democratic autonomy from the rest of China.

After President Donald Trump signed the act, the streets of Hong Kong reportedly filled with thousands of people brandishing American flags. Perhaps, as the Ukrainian soldier once told my brother me, those protesters, more than anything, just needed to know they weren’t alone.

After months of protests, Beijing announced in May that it would tighten its grip on Hong Kong under a new “national security” law. And yet, thousands of Hongkongers again took to the streets on Friday to celebrate the first anniversary of police crackdowns on their demonstrations.

It takes a lot of guts to risk your life for a cause. And you have to be motivated by something more powerful than the fear of death to do it. Looking back, I now understand that the American flag symbolizes more than the republic for which it stands. Our flag also symbolizes self-evident truths about the human spirit.

It’s true that in America we haven’t yet realized the promise of our founding for every citizen. But we better keep trying, because the world is always watching us. Always. And, from what I’ve seen, there are plenty of dark forces in this world held at bay by the simple fact that the American flag still symbolizes a dream worth fighting for.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.