5 Weapons of the American Revolution That You May Have Forgotten About

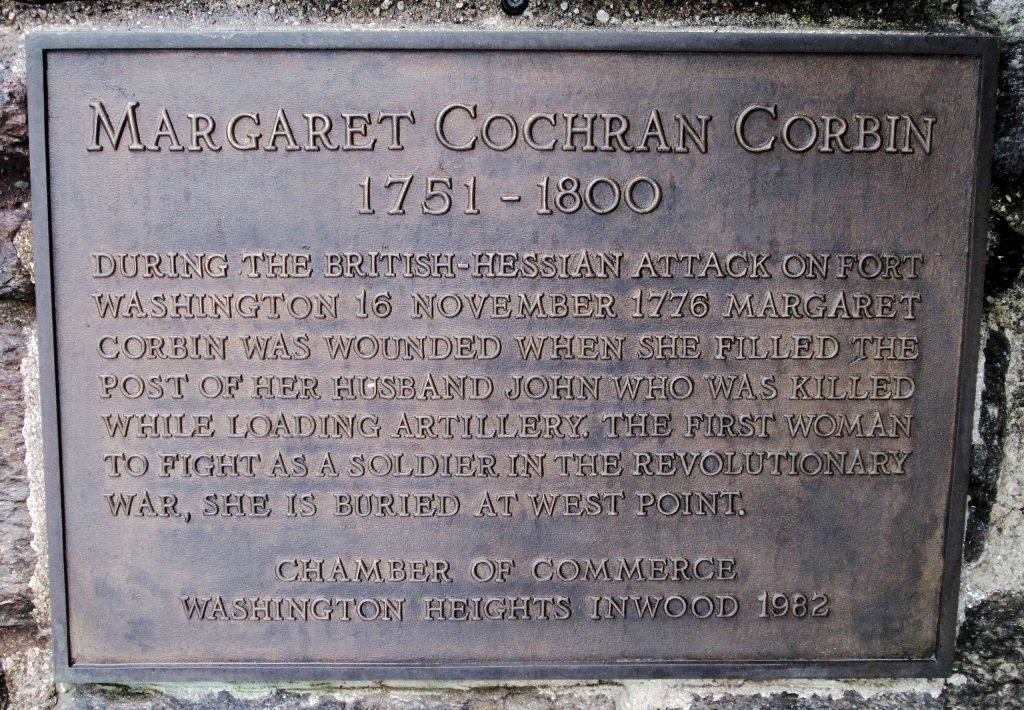

Ten to twelve Hessian fieldpieces were drawn forward to pound Rawling’s riflemen and three cannon, one manned by Margaret Corbin atop of the hill. Artwork by Don Troiani/(http://www.revolutionarywarjournal.com/margaret-corbin-two-years-before-molly-pitcher-captain-molly-was-the-first-woman-to-take-a-soldiers-part-in-the-war-for-liberty/)

The Boston Massacre in 1770 led to the Boston Tea Party in 1773, and by 1775, the 13 colonies had banded together against British tyranny. On the night of April 18, 1775, hundreds of British troops traveled from Boston toward Concord, Massachusetts, to seize a weapons depot belonging to Paul Revere.

The colonial militiamen repelled the British during the Battle of Lexington and Concord the following day. “The shot heard around the world” signified the beginning of the American Revolution.

On July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress voted that they would no longer be subjects of King George III, and on July 4, 1776, they declared their independence and separated from the British Empire. Of course, King George wasn’t going to give up the colonies that easy. The Continental Army fought until 1783 for their new nation, in what would arguably become the most important war in American history.

As significant as the war was, it took place nearly 250 years ago — and the weaponry looked quite a bit different back then. So here are a few of the tools the American revolutionaries used to secure their right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Hand Grenade

Believe it or not, hand grenades were used during the biggest naval battles of the American Revolution, but they didn’t act like modern hand grenades that require the user to “pull the pin” to prime the grenade. American colonists had to light a fuse from the top of these hollow cast-iron spheres. These hand grenades were typically used for boarding operations, and they were devastatingly effective weapons thrown from an experienced hurler.

Captain John Paul Jones commanded the Bon Homme Richard, and his crew squared off against the British ship called the Serapis. The Serpais was a superior battleship, and when Jones ordered his cannons below deck to fire on it before they could get the advantage, two of his cannons in the gunroom exploded, killing many sailors onboard.

With their main guns out of the fight, Jones’ crew switched to a volley of hand grenades. The impact these little iron balls had was unimaginable, as they were thrown into every crevice that the Americans expected to have gunpowder. The tiny weapons of war changed the course of the battle, and the Serpais was disabled.

Long Pattern Musket “Brown Bess”

The most widely used small-arms weapon in the American Revolution was the Long Pattern Musket, commonly referred to as “Brown Bess.” Many civilians armed themselves with these muskets prior to the revolution, so they were readily available among both the British and the colonial militias. The smoothbore, flintlock, muzzle-loading muskets fired circular metal rounds and had an effective range of 175 yards — however, the accuracy leveled off after about 100 yards. Major George Hanger, a British revolutionary commander, said, “Firing at a man beyond a hundred and fifty yards one might as well fire at the moon.”

These Brown Bess muskets were a major upgrade from the previous matchlock weapons that relied on a timed fuse that burned and delayed the time to when a round was fired. When the trigger was pulled on a flintlock musket (such as Brown Bess), the flint was clamped down onto a steel striker, which created sparks to ignite the priming gunpowder. This innovation significantly improved the effectiveness and speed of infantrymen.

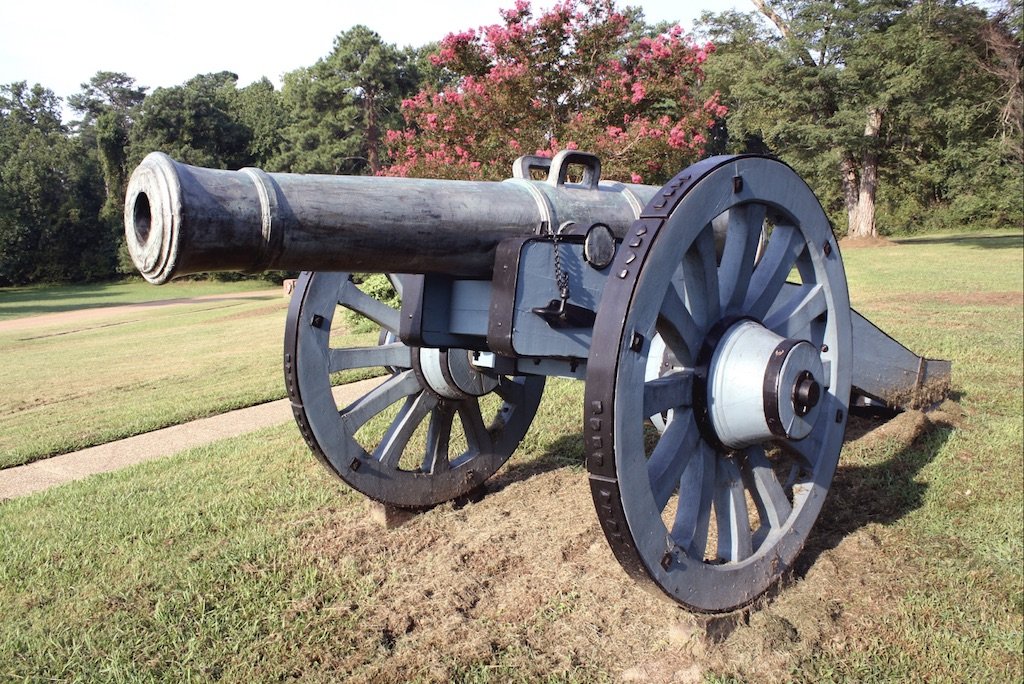

Artillery

During the American Revolution, the Americans, British, and French employed artillery such as cannons, howitzers, and mortars with catastrophic results. Cannons had a maximum range of 2,000 yards with an effective range of 1,000 yards; howitzers and mortars had respectable maximum ranges of 1,300 and 1,400 yards with an effective range of 750 yards. Molly Pitcher, an American folk hero, was based on the stories of a few courageous women, each with legendary reputations. Mary Ludwig Hays McCauley’s husband, William Hayes, served as a gunner in the 4th Artillery of the Continental Army. During the Battle of Monmouth, which was the longest single-day battle in the American Revolution, her husband was killed, and she took his place on the firing line.

“A woman whose husband belonged to the artillery and who was then attached to a piece in the engagement, attended with her husband at the piece the whole time,” wrote Joseph Plumb Martin, a Continental Army soldier present at the battle. “While in the act of reaching a cartridge and having one of her feet as far before the other as she could stemp, a cannon shot from the enemey passed directly between her legs without doing any other damage than carrying away all the lower part of her petticoat. Looking at it with apparent unconcern, she observed that it was lucky it did not pass a little higher, for in that case it might have carried away something else, and continued her occupation.”

Margaret Cochran Corbin was known as the first woman to fight during the American Revolution. Similar to McCauley, Corbin was affectionately called “Captain Molly,” and her husband also served in the 4th Artillery of the Continental Army, but during the Battle of Fort Washington on Nov. 16, 1776. As her husband lay wounded, Captain Molly manned the cannon and loaded and fired cannonball after cannonball for over an hour. Her accuracy was relentless and the British aimed a dozen cannons at her position. By the time the dust settled, Corbin was seriously wounded by grapeshot that mutilated her body and face. She survived, but had long lasting effects for the rest of her life.

Tomahawk

The tomahawk is one of the finest multipurpose tools in a soldier’s arsenal. It can be used for breaching doors, breaking glass, and in hand-to-hand combat. Its effectiveness has carried it into modern wars including the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), but was most commonly used by Native American Indian tribes and soldiers from the Continental Army during the American Revolution. The average soldier could fire their weapons three times a minute — but when multiple adversaries were charging their position, one just didn’t have the time to reload.

The end user of the tomahawk relied on its dependability, and its simplistic design made the edged weapon one of the preferred choices for close-quarters combat.

David Bushnell

Can a man be described as a weapon? David Bushnell was an American inventor with exotic ideas. When he wasn’t studying religion, mathematics, geometry, or natural philosophy at Yale University, he spent his free time developing underwater mines. His experiments with underwater explosions threw water as high as small buildings, and it was quite the sight for curious onlookers. When the American Revolution kicked off, Yale University closed down, so Bushnell went home to Saybrook, Connecticut, and continued his mad scientist experiments. He recruited his brother, Erza, and together the pair developed the Turtle, the first ever submarine that was used in warfare.

The Turtle’s hull was made of oak and had fixed valves, pumps, and two propellers that moved the submarine back and forth as well as aided with the ascent and descent. His ingenuity with his “blades of a windmill” propellers were considered Bushnell’s greatest contribution for future marine developments.

In addition to his submarine, Bushnell developed a sea mine that mirrors what today’s U.S. Navy SEALs use. Navy SEALs take limpet mines and magnetically attach them to the metal side of a targeted warship’s hull before disappearing into the night to await the explosion. Bushnell, more than two centuries before, had packed 150 pounds of gunpowder in what can be assumed was a keg-shaped canister, towed it along the Turtle, then attached the sea mine to an enemy battleship using a wooden hand crank to secure it to the wooden ship. That was the theory he envisioned, of course, and he went one step further by recruiting Isaac Doolittle, a clockmaker, to add a timed fuse to his device.

Although his attempts at underwater demolition of British warships failed, George Washington was so impressed that he gave Bushnell a commission in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers at West Point Military Academy. He became known as the Father of Submarine Warfare.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.