Army Reopens 1 Soldier’s Case in Recruiting Scandal, But Advocates Say Thousands Await Justice

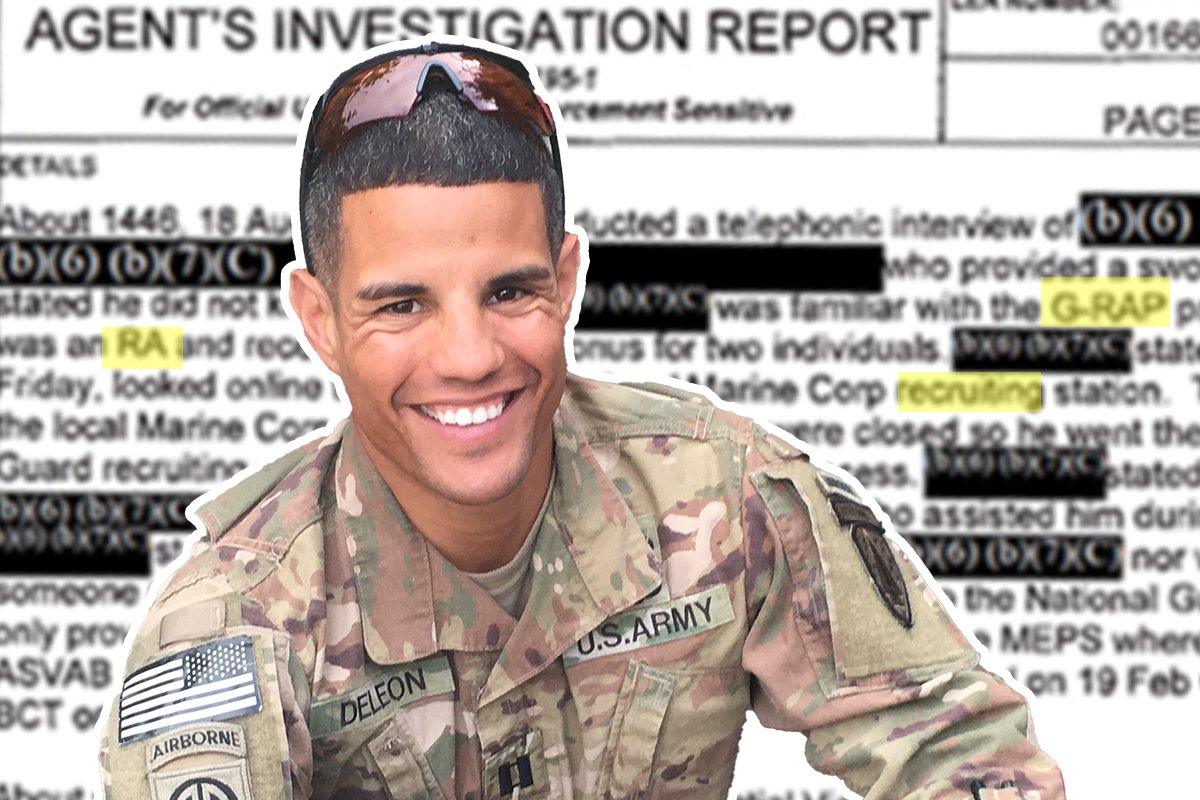

The Army Criminal Investigation Division confirmed it would re-interview Capt. Gilberto De Leon, who says he’s being blocked from promotion because of an unfair flag on his personnel records dating to the now-defunct National Guard Recruiting Assistance Program. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Army investigators have reopened the case of a captain who says he’s being blocked from promotion because of an unfair flag on his personnel records dating to the now-defunct National Guard Recruiting Assistance Program, or G-RAP.

Capt. Gilberto De Leon, who previously shared his story with Coffee or Die Magazine, will be re-interviewed by the Army’s Criminal Investigation Division (CID) in early May, a CID spokesman and other sources confirmed to Coffee or Die. De Leon says his promotion to major has been held up since 2019, flagged for a fraud investigation tracing back to his 2007 participation in the recruiting program. The program was found to have been rife with problems and fraud at the national level, but De Leon is one of thousands of service members who participated and were never charged with a crime.

More than 100,000 people received payments through G-RAP, which offered serving soldiers up to $2,000 for each new recruit they helped bring into the National Guard. But the Army ended G-RAP and its Army Reserve counterpart in 2012 following allegations of widespread fraud and mismanagement, as well as federal findings that the Army had improperly awarded marketing firm Docupak a contract to run the program.

The Army then launched Task Force Raptor, believed to be its largest investigation ever, looking into all 106,364 people who had received payments through the program. The investigation appears to have stuck countless soldiers with a criminal record, even if they were never formally charged or later had the charges dropped.

Lawyers Allege Constitutional Rights Violations

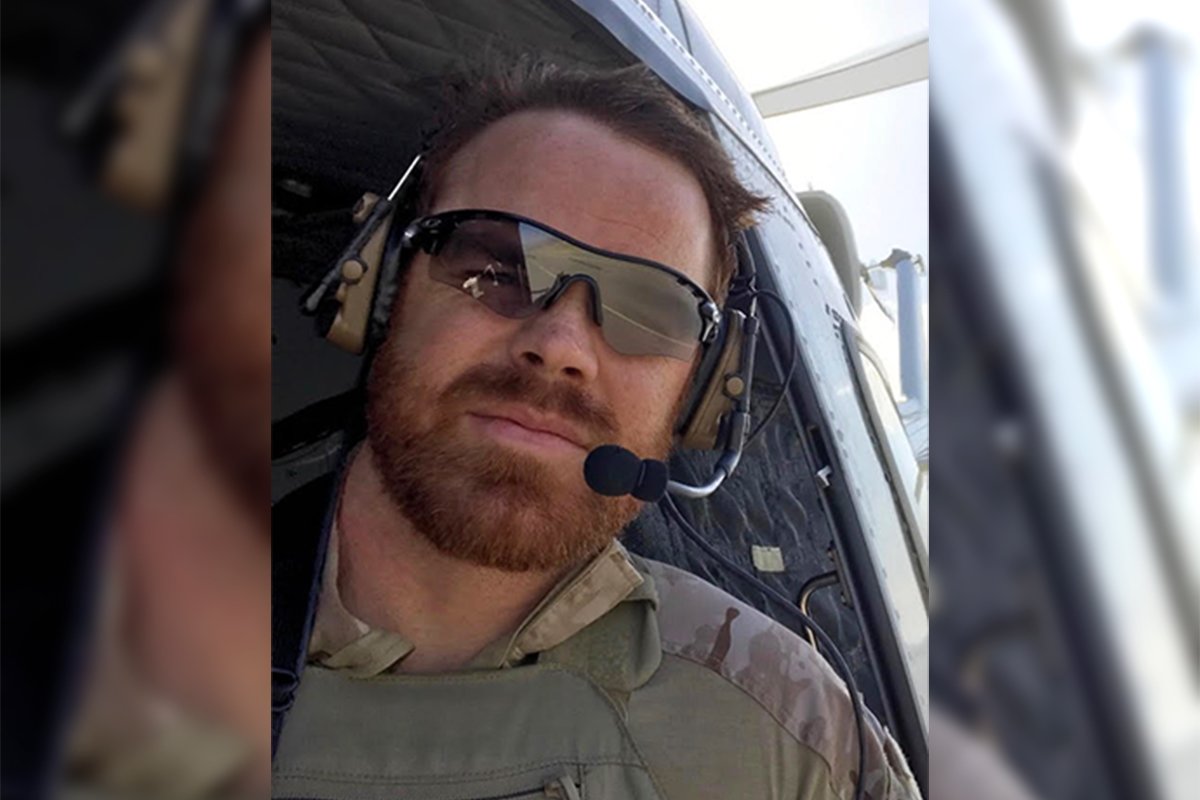

In the fall of 2005, Luke Peelgrane was on top of the world. The 21-year-old had graduated from the Special Forces Qualification Course at Fort Bragg and returned to his home state of Colorado to join the Special Forces team at Fort Carson and wait for his first deployment in the Global War on Terrorism.

Meanwhile, he heard about a Guard recruiting program that was paying soldiers $2,000 a pop for anyone they brought into the service, so he signed up as a way to earn some quick cash. Over the next four years, he made $13,000, enough to help pay to finish his degree at the University of Colorado and offer him a landing pad when he returned from combat in Iraq.

But one afternoon in 2014, years after he’d put G-RAP in his rearview mirror, Peelgrane got a call from his company commander.

“Luke, I received a call from CID yesterday that the Adam’s County District Attorney is issuing a warrant for your arrest on Monday,” Peelgrane remembers the man saying.

“For what?”

“For your participation in G-RAP.”

On Feb. 4, 2014, Peelgrane turned himself in at his local police station, one of at least three Colorado Army National Guard members charged at the time with fraudulently collecting thousands of dollars in referral bonuses.

That same day, Sen. Claire McCaskill, D-Mo., said in a congressional hearing that the G-RAP fraud investigation was “one of the largest that the Army has ever conducted, both in terms of sheer volume of fraud and the number of participants.”

“We now know that thousands of service members, their families and friends may have participated in schemes to defraud the government they served and the taxpayers,” McCaskill said.

Around 125 soldiers were eventually charged in federal or state courts, said retired Special Forces Col. Doug O’Connell, a lawyer who estimates he’s represented around 225 former recruiting assistants in both criminal and civil cases. While soldiers’ advocates agree there were a small number of people who legitimately defrauded the program by providing Docupak with the names of recruits they had never met, the advocates characterize the CID’s investigations as bureaucratic at best and corrupt at worst.

“What we’re talking about is — on a massive level — wholesale constitutional rights violations of the very people who are charged with protecting our Constitution,” O’Connell said. “It’s absolutely crazy.”

The Blurred Line Between an Arrest and a Title

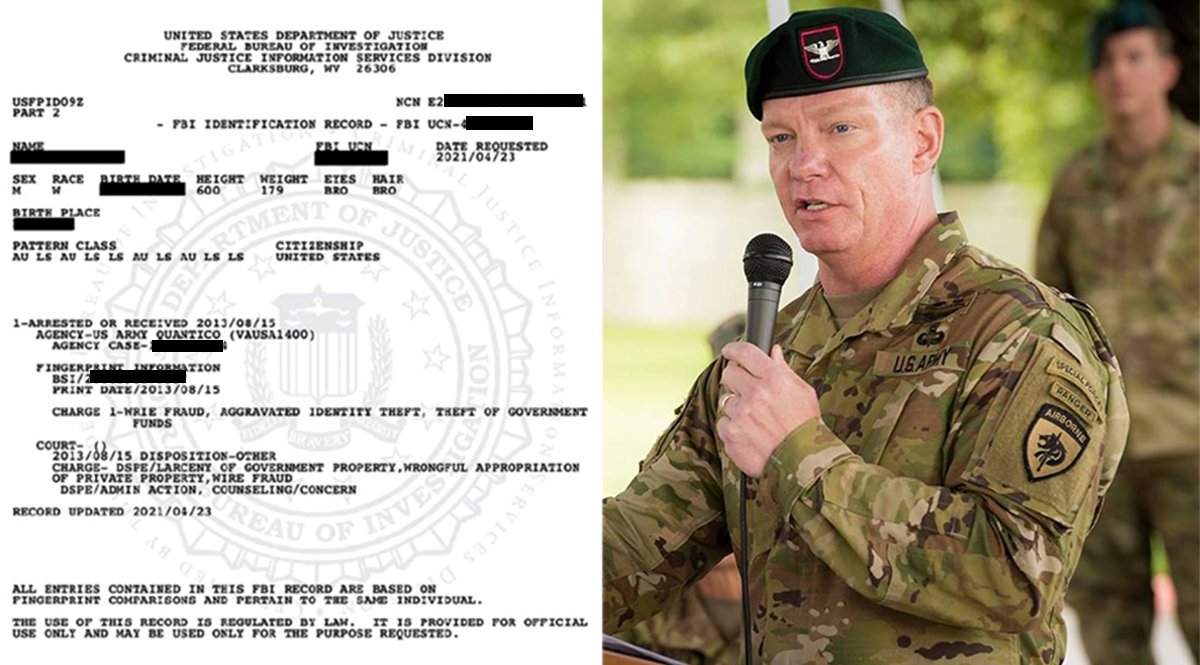

Many of the soldiers who were investigated but never charged with wrongdoing, like De Leon, did not know their records had been flagged until years later. Many only found out when they applied for a promotion, security clearance, license, or anything else requiring a background check. Then, an FBI database would pull up an arrest record from the Army that listed charges such as wire fraud, larceny, identity theft, and theft of government funds, according to background check results O’Connell shared with Coffee or Die.

“There’s a legal definition of what it means to be arrested; it means you’re detained and you’re not free to leave,” O’Connell said. “In the vast majority of these G-RAP investigations, the CID agents never actually made face-to-face contact with their suspect. They might have talked to them on the phone, they might not have. But they were certainly not arrested.”

According to O’Connell and Jeffrey Addicott, another attorney representing soldiers in G-RAP cases, the false arrest records occur because of a process known as “titling.” When CID investigates someone — even if they are never charged with a crime — that person can be “titled,” meaning their name is entered into a report of investigation. Once someone is titled, their name goes into the Defense Central Index of Investigations, or DCII, a database of investigations conducted by DOD agencies that can be accessed by both military and civilian agencies.

The consequences of having a title on one’s record extend far beyond the military.

O’Connell represented one veteran who learned of her criminal history when she applied for a medical license. In another case, a police officer was called into his boss’ office and grilled about why he’d never told them he was arrested. In still another, a law student was flagged when he applied to the state bar.

“I believe there’s tens of thousands of other folks out there who have a criminal history and they just don’t know it yet,” O’Connell said.

O’Connell has often had success getting his clients their jobs back or licenses approved, though it’s an arduous process that involves submitting thick legal briefs and attempting to explain the convoluted history of G-RAP to human resources departments and government officials. And it’s often a temporary victory — the next time the client applies for something requiring a background check, the title will still be there.

According to an Army document, the only way for a soldier to get a title removed is to prove that it was a case of mistaken identity, which does not apply for most soldiers investigated for participating in G-RAP.

A CID spokesperson could not say how many service members had been titled in connection with G-RAP, nor how many titles had been removed from soldiers’ records.

In an email, the CID official wrote that the titling process is separate from the creation of a criminal record.

“(National Crime Information Center) records are created through the submission of fingerprints, which does not occur until investigative efforts derive sufficient evidence to establish probable cause that the individual in question committed the offense(s) alleged,” the CID spokesperson wrote.

But lawyers disagree, saying the titling process sticks soldiers with misleading criminal records that are virtually impossible to expunge.

Peelgrane says he spent months and around $130,000 building a defense against his criminal charges, which were ultimately dropped. By then, the Green Beret had lost his entire life’s savings, his fiancee, and his passion for serving his country. After 14 years in the National Guard, he left the military, later founding Clandestine Media Group.

Leaving the G-RAP stigma behind has been much harder to do.

None of the news outlets that had reported his arrest wrote updates when the charges were dropped. Headlines with “theft” in the title are still among the first results when you search Peelgrane’s name on Google, which he says has led some prospective clients to not do business with him. And even though his criminal charges were expunged, every time someone runs a background check on him, it lists a 2012 Army arrest — which he says never happened and is, oddly, two years prior to his actual arrest.

Peelgrane says banks have attempted to deny him an account as recently as this year, and he was denied the ability to purchase a firearm because his record showed he had been arrested for a felony. Still, he says he has successfully rebutted most of the recurring obstacles.

“I went through a nightmare in 2014,” he said. “It was literally the worst thing I’d ever been through in my life. It wiped out every bank account I had, it destroyed my reputation, and at the end of the day, I was found innocent. There was no ‘sorry,’ no attempt to right the wrong. And then, on top of that, here we are, 12 years after the fact, and I’m still having to worry about it.”

Peelgrane likens the experience to post-traumatic stress, saying he lives in constant fear of being accused of wrongdoing.

“When I participated in the G-RAP program, at no point did I think that I was getting one over on the system or that I was doing something illegal,” he said.

‘My Peers Are All Majors Now’

Multiple Army veterans and currently serving soldiers told Coffee or Die their participation in G-RAP led to promotions being delayed or, in some cases, flat-out rejected.

Retired 1st Lt. Llewelyn Hughes, who spent much of his career enlisted, said he first learned he’d been flagged for participating in G-RAP when he was passed over for promotion in 2015. That same year, he was interviewed by CID about one of the six recruits he had brought into the National Guard through the program. In 2016, he says his attorney informed him that his case was not being referred for any criminal charges. But the next year, the flag was still on his record and he was again passed over for promotion.

“There was no due process,” Hughes said. “Nobody, nobody had a fair opportunity. And then you get put in this perpetual cycle where your peers are advancing while you stagnate as a first lieutenant. My peers are all majors now.”

During a drill weekend in the summer of 2019, Hughes says his unit’s intel officer pulled him aside and said he’d received instructions from the National Guard Bureau that Hughes needed to be fingerprinted. But the intel officer, a man Hughes knew well, advised him not to give his prints.

“‘Look dude, that’s the same as you being convicted of a crime in the way that they do a security background check,’” Hughes remembers the intel officer telling him.

Hughes left drill that evening and submitted his resignation the next morning.

“I saw the writing on the wall,” he told Coffee or Die. “I recognized the depth and perversion of what that G-RAP investigation had become. I was retirement-eligible, so I dropped my retirement paperwork before they could do something that would put my retirement in jeopardy.”

Hughes appears to have dodged the titling bullet — he says he’s never had an issue with a background check since leaving the National Guard, and he has been able to obtain top security clearances in his job as a security operations chief within the Department of Commerce, a role that includes frequent interactions with the Secret Service.

“I never would have been hired in this position if I didn’t have that security clearance,” Hughes said.

Lawmakers Call for Change

Officials with Army CID would not say whether the department is reopening cases beyond De Leon’s, but a small group of Republican lawmakers has called on the Defense Department to make a change.

Last month, GOP Reps. Louie Gohmert, Paul Gosar, Daniel Webster, Madison Cawthorn, Barry Moore, and Ralph Norman signed a letter asking Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and other officials to intervene on behalf of De Leon and to change DOD rules that govern the DCII so that, in cases where a member is exonerated through a court proceeding — including if charges are dropped without a verdict or trial — they will be purged from the DCII’s rolls. While that would help veterans like Peelgrane, it’s not clear how it would affect the thousands of soldiers like De Leon who were investigated but never charged.

As of Monday, April 25, the lawmakers had not received a response from the Defense Department, a spokesperson for Gohmert told Coffee or Die.

Many soldiers and their advocates hope the CID will eventually be forced to withdraw criminal histories based on titling.

“Nobody ever questioned the government for wasting millions of taxpayer dollars on first the program and then the investigation,” Peelgrane said. “Instead, the soldiers were the only ones that took blame.”

Read Next: Soldiers Fight To Clear Their Names Years After Recruiting Scandal

Hannah Ray Lambert is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die who previously covered everything from murder trials to high school trap shooting teams. She spent several months getting tear gassed during the 2020-2021 civil unrest in Portland, Oregon. When she’s not working, Hannah enjoys hiking, reading, and talking about authors and books on her podcast Between Lewis and Lovecraft.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.