A World War II POW and the only female Medal of Honor recipient are among the dozen women who may help rename bases with Confederate names. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

A World War II POW and a Civil War Medal of Honor recipient are two of the dozen women who may replace Confederate generals as namesakes for nine military bases.

Last March, Congress created a special eight-member commission to study the costs of renaming or ditching bases and landmarks paying tribute to the Confederacy, and to recommend new names as appropriate. In its first public act, the Naming Commission on March 17 published a list of 87 possible replacement names, all but two of them recognizing notable Americans who supported the U.S. military in some way. (“Central Texas” and “Courage” are the outliers.)

These names were curated from over 34,000 submissions from the public over a recommendation period last year. On its website, the Naming Commission stated it had “deliberated extensively” over all the suggestions to come up with its list of finalists.

Including 12 women on the list is a deliberate statement: no U.S. military base is named for a woman, although women have been fighting for the nation since the American Revolution and wearing the uniform in at least some capacity since World War I.

In 2020, Rep. Norma Torres, a California Democrat, introduced an amendment to the defense budget bill to encourage the Defense Department to consider female base namesakes. Congress has given the Pentagon three years to rename the nine Army bases in question, which include Fort Hood, Texas and Fort Bragg, North Carolina, but in the meantime, Americans may get an impromptu history lesson about some overlooked military heroes.

Here are the 12 women who might make history – again – as a base namesake.

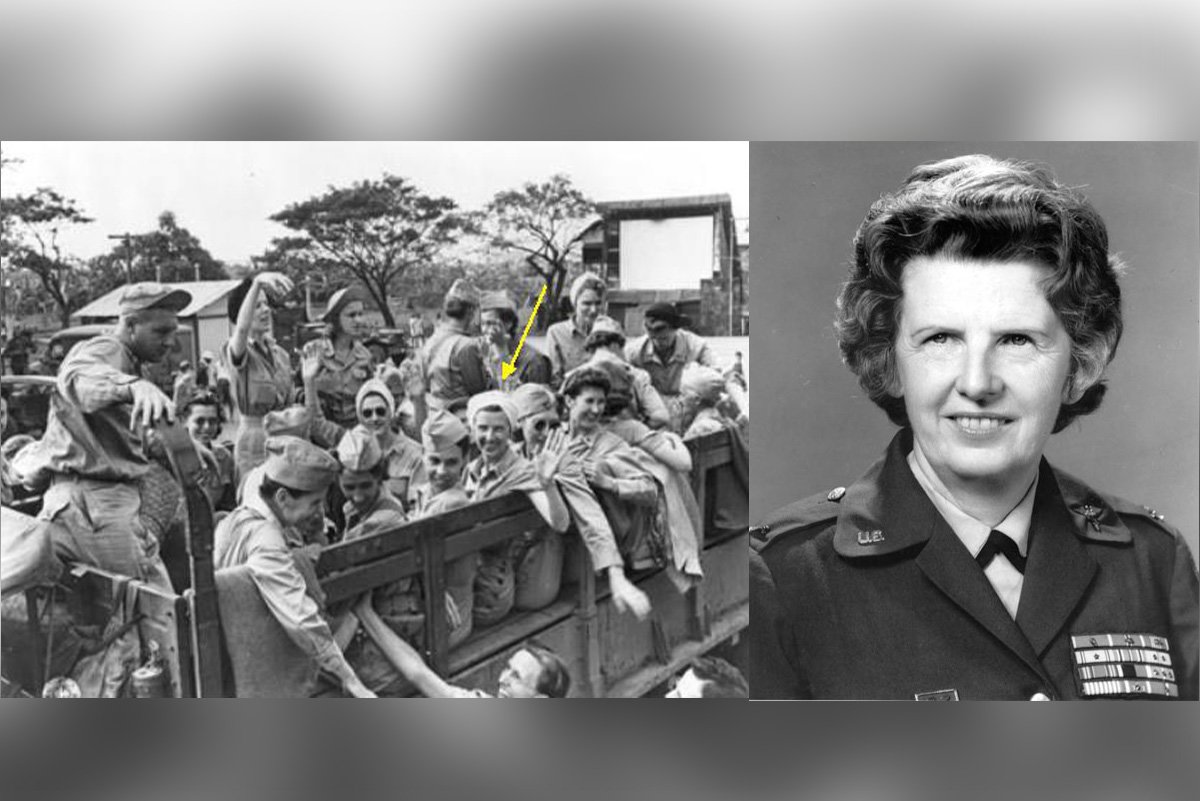

Ruby Bradley

This tough-as-grit Army nurse refused to stop serving in uniform, even after spending three grim years as a Japanese prisoner of war. Bradley was captured on Dec. 23, 1941, while deployed to Camp John Hay in the Philippines as a hospital administrator. During her 37 months in two POW camps, she’d earn the nickname “Angel in Fatigues.” By her count, she assisted in 230 major surgical operations and delivered 13 babies in captivity, and she often cut back her own meager rations so she could feed children in the camp. By the time she was freed by U.S. Army liberators in early 1945, she weighed only 86 pounds.

Her sportiest fighting days weren’t behind her, though. She deployed at the start of the Korean War in 1950, serving as chief nurse for the 8th Army’s 171st Evacuation Hospital in Pyongyang. When the hospital was attacked by Chinese soldiers, she refused to board an evacuation aircraft until she had gotten all her patients on board. She accomplished this task and climbed aboard just as a Chinese shell blew up the ambulance behind her.

Bradley would retire as a colonel in 1963 with a stack of awards including two Bronze Stars, two Legion of Merit Medals and a Florence Nightingale Medal presented by the International Red Cross. To this day, she is among the most decorated women in U.S. military history.

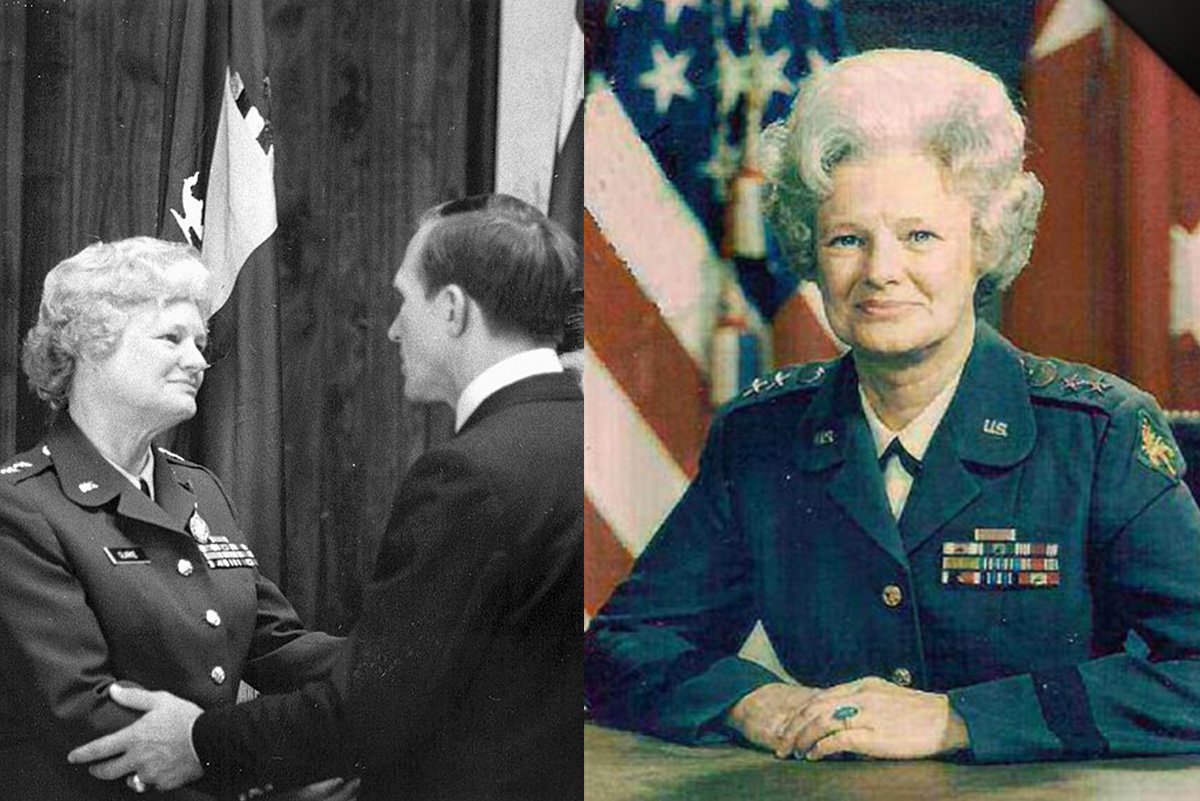

Mary Clarke

To rise in the ranks from private to major general is an impressive feat even today, but Mary Clarke did it while women still fought for full standing in the military. Clarke, who went by Betty, enlisted right before the end of World War II and served for four years as a supply sergeant and a recruiter before earning a commission in the Women’s Army Corps in 1949. WAC, started in World War II as a kind of emergency women’s auxiliary, would come to an end on her watch: as a brigadier general in 1978, she was its last commander.

Clarke was the first woman to command a major military installation when she took charge of the United States Army Military Police and Chemical Schools Training Center at Fort McClellan, Alabama, and she’d make more history when she retired in 1981 after 36 years of service. Her career remains today the longest of any woman in the military.

Charity Early

She’d retire as a lieutenant colonel, the highest-ranking Black woman in the Army at the time. This year, Congress voted to award the women of the Six Triple Eight the Congressional Gold Medal, recognizing outstanding service to the nation.

Kimberly Hampton

Capt. Kimberly Hampton was flying her OH-58 Kiowa Warrior helicopter over Fallujah, Iraq on Jan. 2, 2004, to provide cover for an infantry raid when she was shot down and killed. The first female pilot in U.S. history to die in hostile fire, she had previously served in Korea and Afghanistan. She earned the Bronze Star, Air Medal, and Purple Heart, all posthumously.

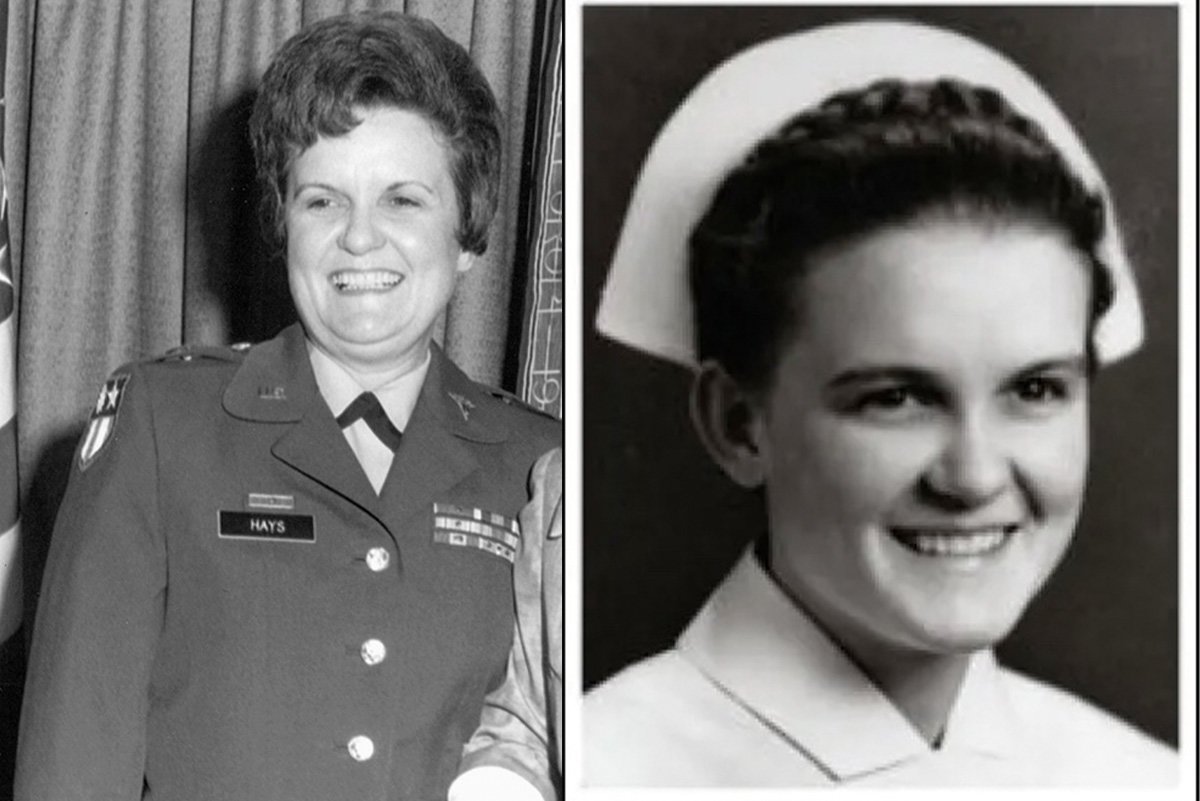

Anna Hays

The first woman in U.S. military history to be promoted to a general officer rank, Anna Mae Hays was determined to leave the service better than she found it. She served in the Army Nurse Corps, deploying to India in World War II, serving in the brutal cold at an Inchon field hospital during the Korean War, and supervising deployed Army nurses in the Vietnam War. In 1967, she was made Chief of the Army Nurse Corps.

As she rose through the ranks, she made a point of calling out sexism and discrimination where she saw it. She recommended the Army stop discharging female officers who became pregnant and pushed for equal treatment and benefits for the spouses of female service members – policies the service ultimately adopted.

Hazel Johnson-Brown

Another chief of the Army Nurse Corps, Johnson-Brown was the first Black woman to hold that position – and the first to be promoted to brigadier general. Enlisting as an operating room nurse just seven years after the military was formally desegregated in 1948, she would go on to earn a bachelor’s and master’s degree and Ph.D. through the Army.

Over her career, she’d train nurses in Vietnam, oversee the 121st Evacuation Hospital in Seoul, South Korea, and later become director of the Walter Reed Army Institute of Nursing.

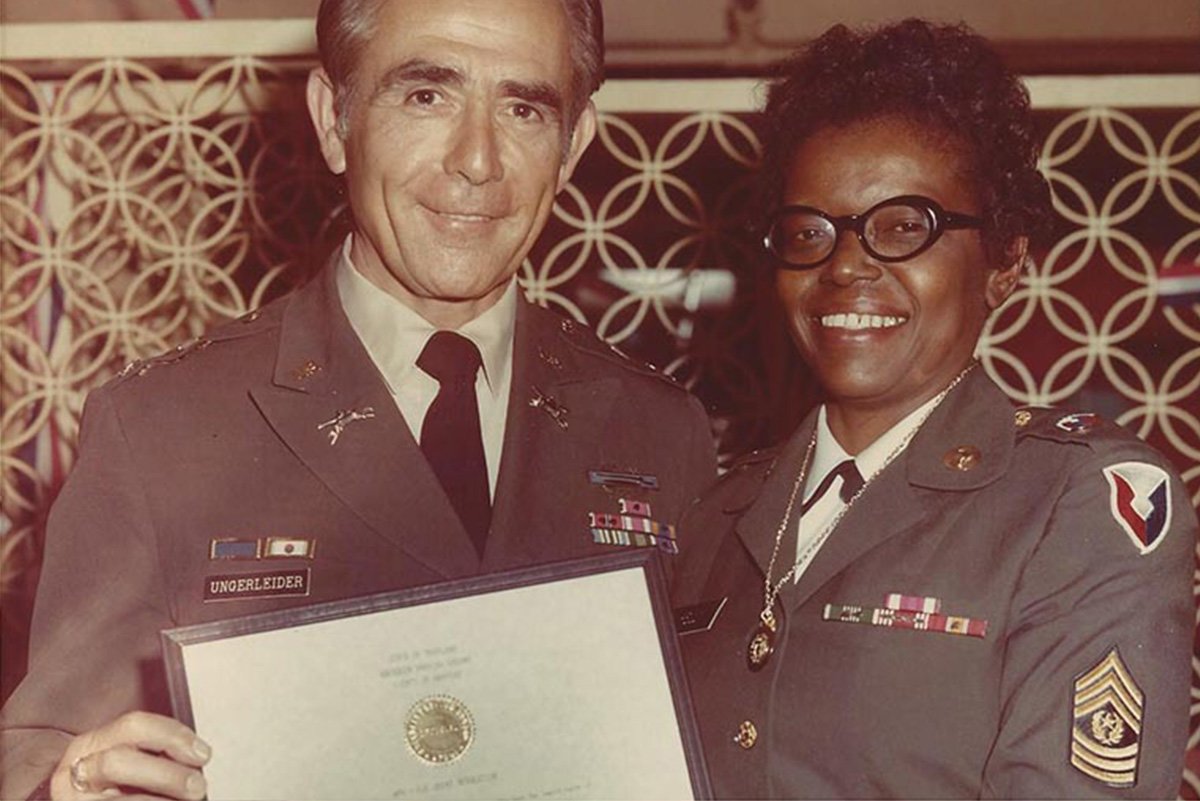

Mildred Kelly

Another Army pioneer, Kelly was the service’s first Black female sergeant major and first female command sergeant major of an Army installation. She earned a degree in chemistry before joining the Army, but opted against pursuing a commission, saying she felt she had more power and influence as a leader in the enlisted ranks.

She was promoted to sergeant major in 1972 while serving at the Pentagon and would become the senior enlisted leader at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland in 1974. Retiring in 1976, she continued to be involved in veterans’ issues and remained a fierce advocate for Black and female veterans for the rest of her life.

Julia Moore (and her husband Hal Moore)

This name recommendation is a twofer, recognizing an Army power couple who rose to the challenges before them in the Vietnam War. Hal Moore, who retired as a lieutenant general, is best known as the commander of 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment in the Battle of Ia Drang, a costly fight documented in the book “We Were Soldiers Once … and Young,” later turned into a movie starring Mel Gibson.

Julia, shown in the movie collecting death notice telegrams as they arrived by taxi so she could deliver them in person to bereaved spouses, was moved by the experience to fight for a more organized and compassionate Army casualty notification system. As a result of her advocacy, the Army adopted its current policy of sending an officer and chaplain in uniform to deliver casualty notifications. Moore would become the namesake of an award recognizing military spouses for “outstanding contributions to the U.S. Army.”

Elsie Ott

A flight nurse in World War II, 2nd Lt. Elsie Ott was the first woman to receive the Army Air Medal, recognizing acts of heroism or achievement while in flight. Stationed in Karachi, India in 1943, Ott was assigned to the first intercontinental air evacuation in history, tasked with transporting five ill and injured patients all the way from India to Washington, D.C. over the course of a week. She’d never flown before, and was given only 24 hours’ notice about the flight.

The trip involved 10 refueling stops and the aircraft picked up 11 additional patients en route. Ott was responsible for caring for all of them with a meager supply of first aid materials that she had assembled on her own initiative. She took careful notes and made a series of recommendations about supplies and preparations that improved later evacuation flights.

Emily Perez

On Sept. 12, 2006, 2nd Lt. Emily Perez volunteered to head out on a convoy with 204th Support Battalion, 2nd Brigade, 4th Infantry Division near Najaf, Iraq, replacing the leader who had been slated to go but didn’t have as much experience. While completing that mission, Perez’s Humvee hit an improvised explosive device, killing her.

She’d be the first Black female officer to die in combat in Iraq, and also the first female graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point to be killed in the war. Remembered as a determined leader who put her soldiers first, Perez’s awards included the Bronze Star, Purple Heart and Army Commendation Medal. A college sprinter, she was also posthumously given the NCAA Award of Valor.

Harriet Tubman

Many people know Harriet Tubman as an escaped slave turned fearless abolitionist who smuggled 70 people to freedom via the Underground Railroad. Fewer know that she played a crucial and high-stakes role for the Union Army during the Civil War. Born into slavery in Maryland, Tubman escaped at age 27 and quickly threw herself into helping others reach freedom, against the law and at great personal risk. When the Civil War began in 1861, Tubman was asked by Massachusetts Gov. John Andrew to assist the Union Army, and she did, serving as head of espionage and using a source network of former slaves in the South to gather information about the Confederate Army’s movements. In 1863, she led an expedition known as the Combahee River Raid, rescuing roughly 750 slaves who had been formally freed by the Emancipation Proclamation from their captivity in the South Carolina low country.

The mission made Tubman the first woman in U.S. military history to lead an armed assault. She’d continue working for the Union Army as a scout and a nurse until the conclusion of the Civil War in 1865. Despite her tremendous contributions to the war effort, Tubman’s military service was rarely recognized publicly, and she had to fight for decades before she was finally granted the $25 monthly pension owed to her as a former soldier.

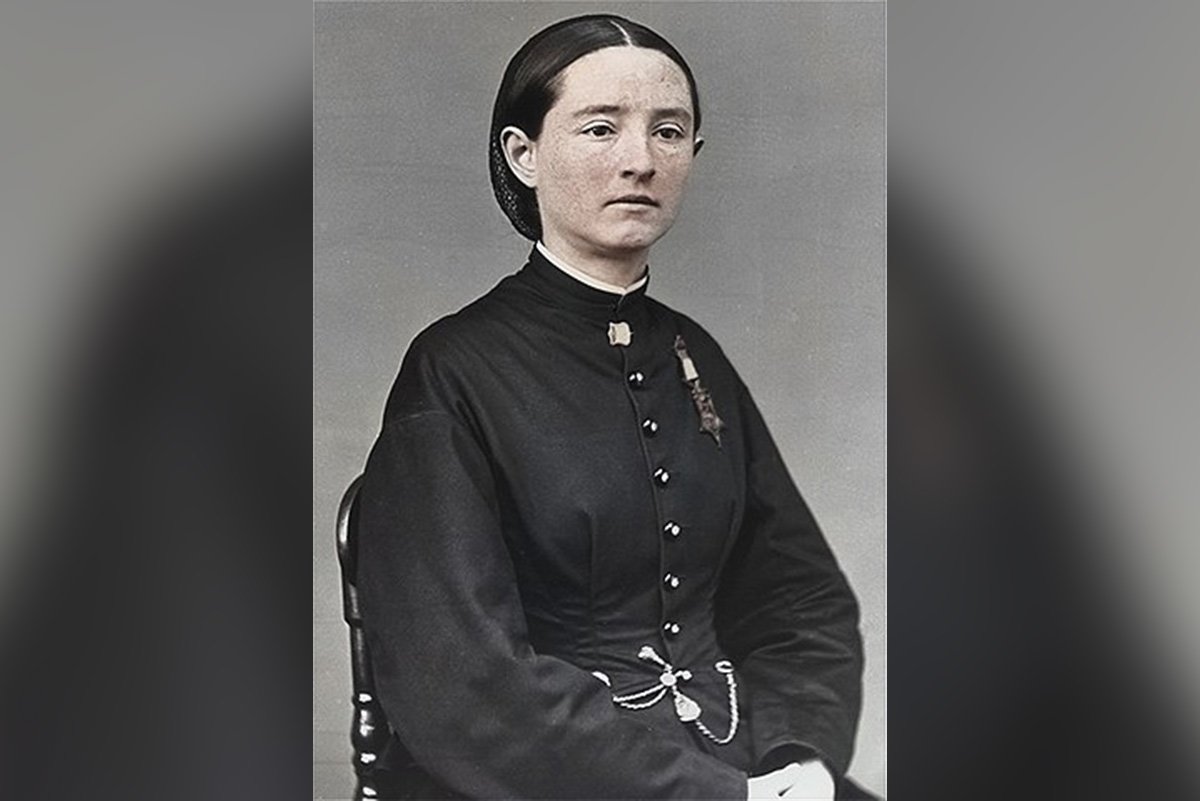

Mary Walker

When the Civil War broke out, Mary Walker was an accomplished surgeon with a private practice. She wanted to serve in uniform, but was turned away from the Union Army because she was a woman. Overqualified to serve as a nurse, she opted to volunteer her skills instead, becoming the Army’s first female surgeon, serving close by some of the war’s most significant battlefields in locations like Chickamauga and Fredericksburg. She wouldn’t receive pay for more than a year, until the U.S. War Department finally recognized her and appointed her as a surgeon in 1863. She treated troops in Chattanooga Tennessee until she was captured in April 1864 by Confederate forces and held for four months as a prisoner of war. After she was released, she went back to work treating patients at a hospital for female prison inmates in Kentucky.

Following the Civil War’s conclusion in 1865, President Andrew Johnson granted Walker the Medal of Honor for her distinguished service. She wore the medal with pride for the rest of her life. It was one of 910 medals rescinded in 1917 amid the institution of new criteria. Since Walker had been denied full military status, she was deemed ineligible as a civilian. Walker ignored this decision, however, and continued to wear her medal until her death in 1919. In 1977, following advocacy by Walker’s family, President Jimmy Carter formally restored the honor. Walker is still the nation’s only female recipient of the Medal of Honor.

This article was originally published on Sandboxx News. Follow Sandboxx News on Instagram.

Read Next: Identities Released of Four Marines Killed in Norway MV-22 Crash

Coffee or Die is Black Rifle Coffee Company’s online lifestyle magazine. Launched in June 2018, the magazine covers a variety of topics that generally focus on the people, places, or things that are interesting, entertaining, or informative to America’s coffee drinkers — often going to dangerous or austere locations to report those stories.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.