Beneath Hill 60: The Heroism of the 1st Australian Tunneling Company

Holding a candle with a flame, commanding officer Oliver Woodward whispered in the darkness to a group of men of the 1st Australian Tunneling Company, informing the engineers he was now in charge. The soldiers, some only teenagers when they joined the Mining Battalion, were wary of Woodward, an officer with no experience on the Western Front.

Woodward bowed his head and crouched through a mine shaft along the Armentières sector in France. A young kneeling soldier handed him a geophone, a listening device placed against the wall. Attached to stethoscope earpieces, Woodward listened intently to try to decipher the source of the sudden noise — the tapping of a miner’s pick, voices of nearby German soldiers, or merely nothing at all.

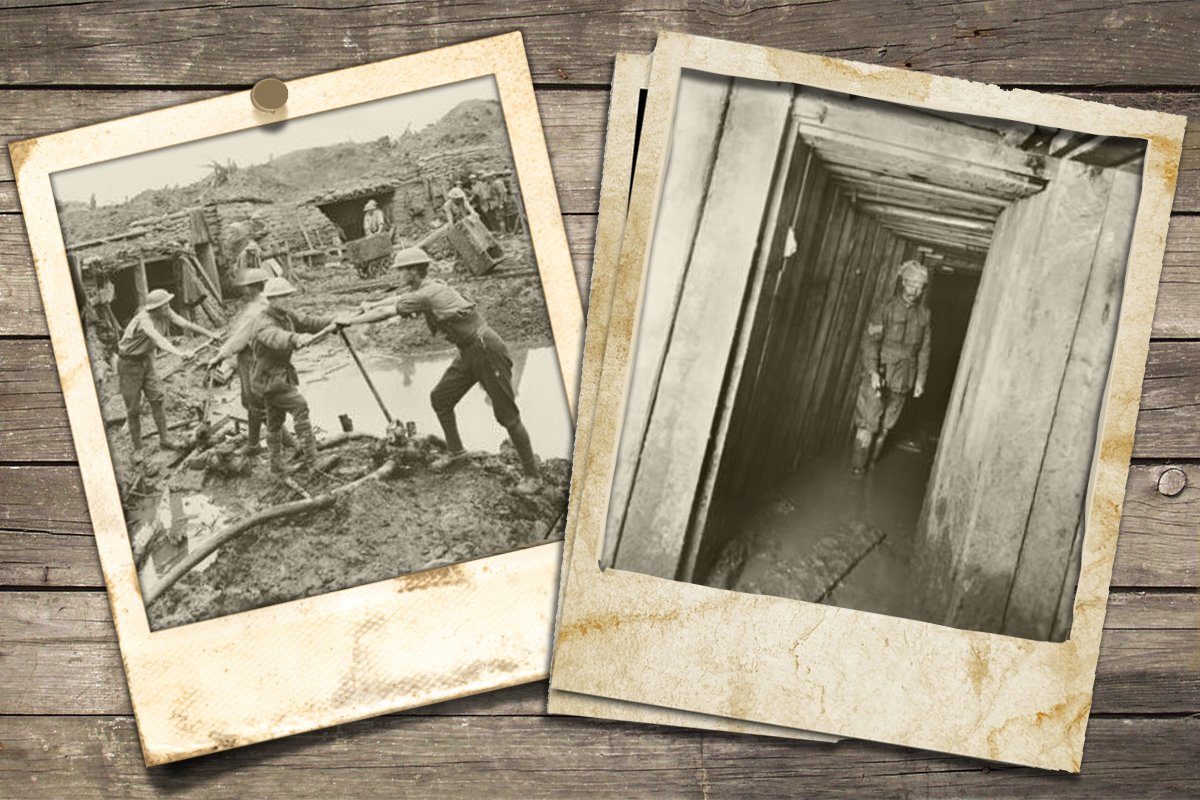

Mine warfare during World War I was both an offensive and a defensive strategy used by both sides. The silent war underground was a chess match, where even the slightest of noises could expose the existence of a tunneling effort to the enemy. Engineers and coal miners established mine shafts underneath the front line, while sappers placed explosives in a chamber at the end of the shaft. The explosions disrupted enemy-held positions, which improved morale and gained a tactical advantage, however slight. These aggressive operations had their dangers, too, including hidden “camouflets“ used to collapse tunnels, trapping soldiers in encased tombs.

Woodward and members of the 1st Australian Tunneling Company were exposed to the horrifying whistles of incoming artillery barrages. The screams of soldiers who suffered from shell shock emboldened the tunnelers to construct underground galleries to be used as shelters. Since the engineers had knowledge of explosives, they were also responsible for aboveground demolition missions across no man’s land.

On the night of June 10, 1916, Woodward and a two-man sapper team were tasked with destroying the “Red House,” a bombed-out home where a machine-gun emplacement and sniper section were holed up.

“At 12 midnight, after a farewell handshake with the other officers, we silently crept over the parapet and were soon on our own side of the barbed wire entanglements,” Woodward recalled to the Northern Star newspaper of Aug. 24, 1916. “From then on the risk was very great, as the Hun was constantly sending up illuminating glares and star shells, which make ‘no man’s land’ as bright as day.”

Sgt. Fraser and Sapper Morris reminded Woodward to remain incredibly still until after the flare fizzled out. Movement only in darkness was their safety, as the machine-gun team fired at anything they detected in motion. They crossed 120 yards of open ground and sought cover in a muddy crater caused by an artillery shell. Woodward crawled forward, carrying a 65-pound explosive charge, and placed it on the side of the Red House.

“After placing the charge, we proceeded to return, I following back the electric cables to see if they were right,” Woodward remembered. “Judge of my consternation when on reaching the halfway mark I discovered that the wires had broken.”

Woodward twice returned to his own trench to acquire enough wire to complete the circuit. While the sappers worked in secret, the Germans from the Red House continued to fire sporadically upon the Australian-held trench, oblivious to Woodward’s operation. Woodward attached the wire to the exploder, returned to his own lines, and pushed the lever down. A massive explosion erased the enemy position.

In October, Woodward received a battlefield commission to make the rank of captain. His unit relocated to Hill 60, a notorious German stronghold in Ypres, Belgium. For three weeks, Woodward led an effort to dig through quicksand, clay, and chalk to sink a shaft down to a gallery beneath an uncharted and unstable area. They used sections of steel to prevent the sand walls from collapsing inward and electric pumps to funnel the encroaching water out of the mines. The ingenious idea, viewed by some as impossible, had never been tried successfully.

Before dawn on June 7, 1917, 21 mines were rigged to explode. Woodward was responsible for the detonation of the final two mines, Hill 60 (53,000 pounds of ammonal explosives) and the Caterpillar (70,000 pounds of explosives).

“Gentlemen, I do not know whether we shall change history tomorrow,” said British Maj. Gen. Charles Harington. “But we shall certainly alter the geography.”

British and Australian tunneling companies initiated the attack, and 19 of the total 21 mines erupted consecutively, one after the other, into a ginormous fireball. Nearly 1 million pounds of explosives caused shock waves reportedly felt as far as London. The largest non-nuclear explosion killed 10,000 German soldiers and was the beginning to a clear victory during the Battle of Messines.

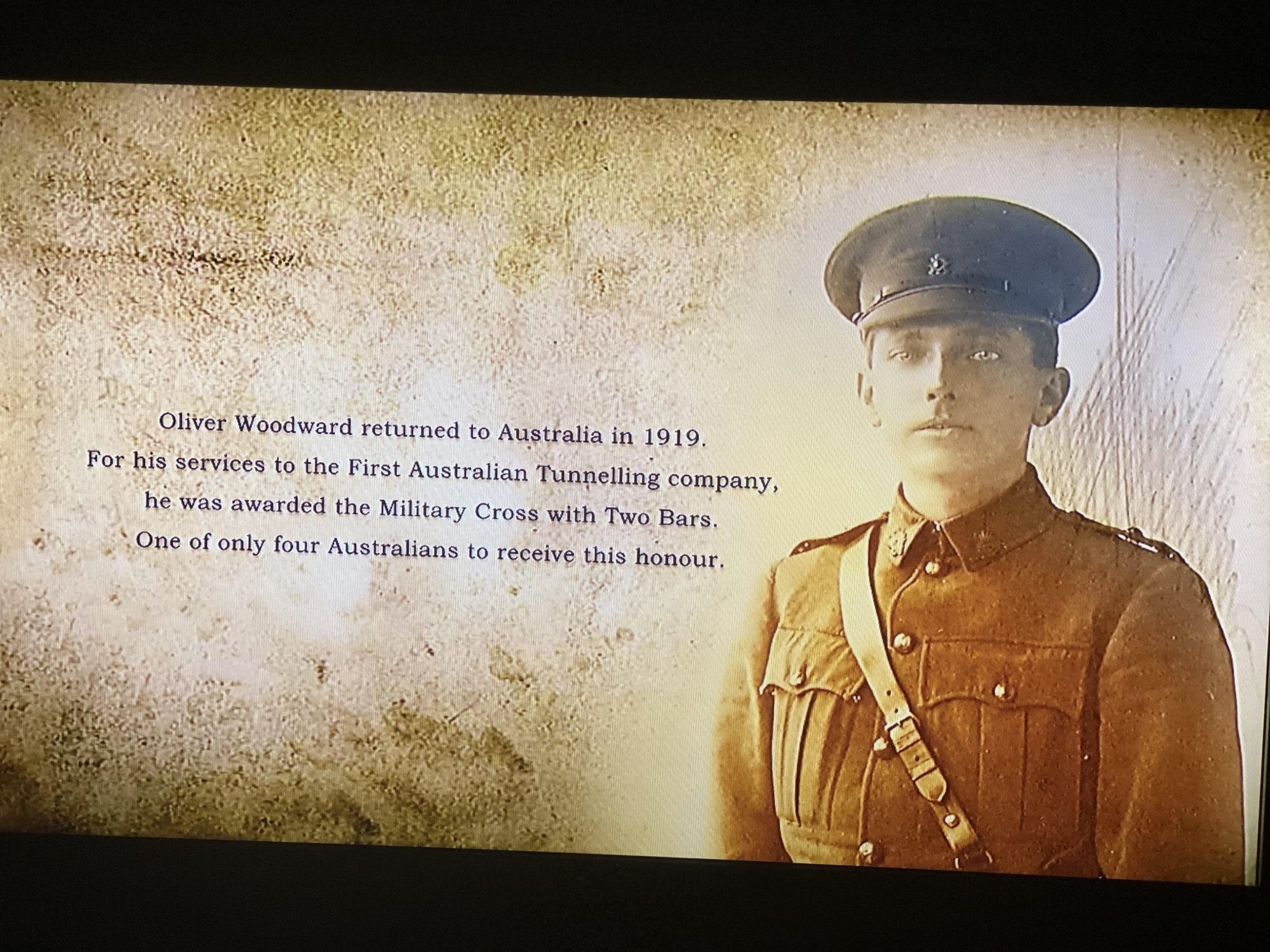

The true story of the 1st Australian Tunneling Company during World War I was expertly told in the 2010 film Beneath Hill 60. For his service, Woodward was awarded the Military Cross with Two Bars, only one of four Australians to receive this honor.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.