Behind a Billboard of Bowe Bergdahl, Khost Maintains Anti-Taliban Ways

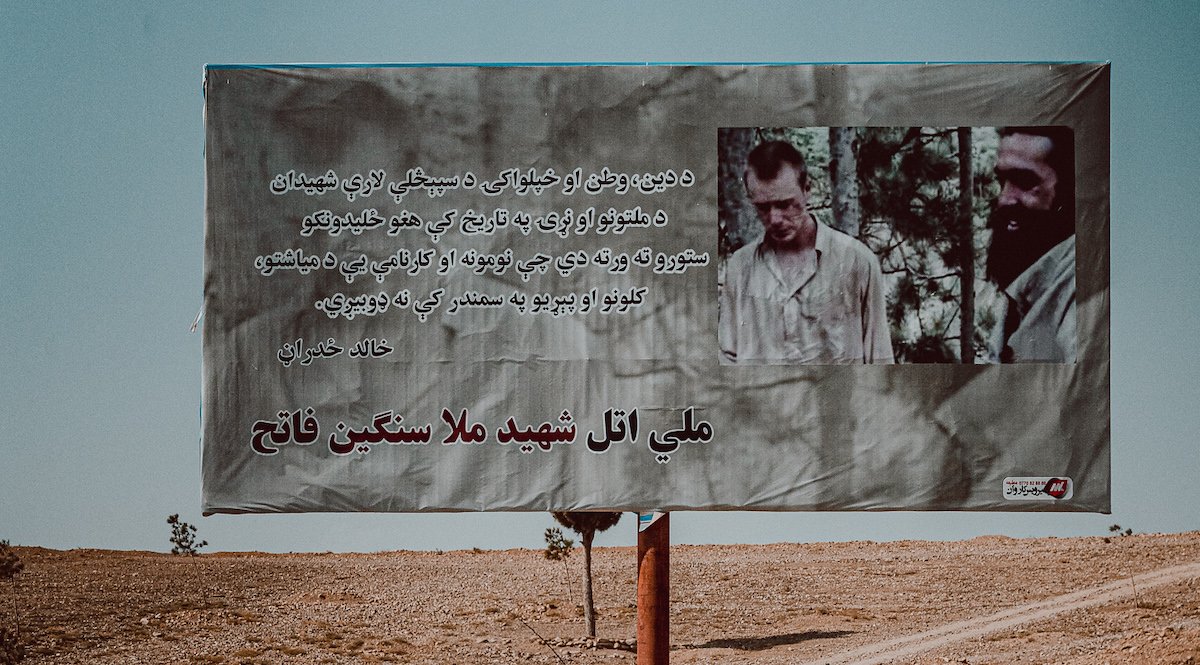

In Khost, a billboard of US Army soldier Bowe Bergdahl and his captor, Mullah Sangeen Fateh. The billboard reads: “Martyrs of religion, country, and holy path are similar to shining stars of nations and world history whose names and actions can’t be drowned in monthly, annual, and decade oceans.” Photo by Jacob Simkin.

KHOST, Afghanistan — It’s one of few stretches of road among these winding hills and twisting valleys that remains paved and intact, untouched by the two-decade war that crippled most of Afghanistan’s land arteries. But the road from Kabul to Khost — 150 miles by way of Logar and Paktika — is a serene drive through a lush and primitive landscape tucked inside the bloodstained land. Yet the province of 650,000 comes with a chilling history. It’s home to much of the Haqqani family, and this thoroughfare was long used for al Qaeda and Taliban operatives to trundle in and out of the Pakistani tribal region of Waziristan, where extremist madrassas and training camps have flourished.

On a dusty field in the city of Khost, a giant billboard lit by fall sunshine caught my eye.

It features Bowe Bergdahl, the US Army soldier who deserted his post in the neighboring province of Paktika and was ultimately held captive by the Taliban-affiliated Haqqani Network from 2009 to 2014. He was released on May 31, 2014, as part of a prisoner exchange for five high-ranking Taliban members — one of whom is now the provincial governor — held at Guantanamo Bay.

“Martyrs of religion, country, and holy path are similar to shining stars of nations and world history whose names and actions can’t be drowned in monthly, annual, and decade oceans,” the Pashtun poem by Khalid Zadran reads alongside the picture of a distraught-looking Bergdahl and a smiling mullah named Sangeen Fateh.

The Bergdahl billboard in Khost is less a celebration of the captured American than a tribute to Fateh, who was killed in 2013 by a US drone strike and is remembered as a favorite leader among the Haqqani. In another busy spot in the city center, a billboard featuring Fateh reads, “Afghan Mujahed who closed the invading American soldier’s eyes and tied his hands and made the West realize the outcome of the invasion.”

As I walk the streets, though, none of the civilians I speak with really seem to know why the glaring billboard is there — even though the Khost governor is Mohammad Nabi Omari. He was one of the five men exchanged for Bergdahl.

Still, despite its celebration of anti-American resistance during the war, Khost surprisingly remains something of an anti-Taliban resistance stronghold, largely driven by the fact that it remains a deeply tribal society with its own unique Pashto dialect and leaders not aligned with the Taliban.

Uniquely of anywhere I have been in Afghanistan, the red, black, and green flag of the toppled Afghan government — the emblem of the Islamic Republic defeated by the Islamic Emirate — still flies high.

In fact, the old flag is everywhere — across rocky mountain cliffs and atop shop windows, and even inside government buildings, including those belonging to the provincial education ministry. It sometimes flaps next to the white-and-black Taliban flag, other times by itself, unchallenged. Some shopkeepers vow that they will not let the Taliban take their old government flags down.

“We won’t let them touch our flag,” one women’s rights activist and schoolteacher told me. “These (Taliban) men need to show us they have changed, that they aren’t like they were and that they will give women the full rights.”

Certainly, Khosti women are tough. Many activists still show up to work each day — including teachers of now halted girls’ high schools — in defiance of Kabul’s rule against girls’ schools.

As a profoundly tribal society, Khost is a mosaic of ancestral clans and family connections. It is a place where the village elders rule, not the Taliban. Locals are quick to point out the numerous Taliban “no go” zones. “The Taliban knows they can’t come here,” my driver quipped, chugging up a mountain road. “Besides, there are often fights between tribes, and the Taliban doesn’t want to have to get involved with that. The village leaders have the final say, and the Taliban won’t mess with them.”

And in contrast to most places I have visited, the local population has neither hesitation nor fear in speaking out against the new government.

Some anti-Taliban residents speak of the mountain militia in disgust, cursing the death and destruction it has caused and contorting their faces at the mere mention of the Taliban’s trademark long hair and beards.

“I remember all the things they did to us in the previous rule, whipping us and not letting us learn,” one grandmother said. “They cannot expect quick forgiveness.”

Others openly prefer to consider themselves communists.

“I will never grow a beard or dress like them,” one impassioned laborer said, wanting to know how such a rugged look was viewed in the Western world. “I will deliberately only ever have a mustache.”

“We love our government forces,” another older woman with a house filled with daughters and granddaughters told me. “Many of the special forces were from Khost, and we stood with them and the Americans the whole way.”

The more you move through Khost, the more a picture of fierce independence emerges. Almost every home or shop is adorned with solar panels to avoid reliance on other countries or provinces for electricity. Khost people take charge of building their own roads and critical infrastructure.

Over at the Education Ministry, newly appointed Taliban officials — some of whom have also spent years in jail on terrorism-related charges — are quick to point out that they have already outfitted institutions with appropriate segregated classrooms for girls and are just waiting for the green light from Kabul to resume school.

“But if we don’t get a date soon, we will set our own date and just begin again,” one university department head said. “And we will have a special ceremony, just for the women.”

In Khost, I encounter the first instances of men — including a number of Taliban members — not only looking me in the eye but also shaking my hand.

The Taliban-installed mayor of Khost City, Bassmilla, spent six years behind bars at Bagram for purporting to detonate a suicide bomb. He was released last year as part of the Doha-inked US agreement to release 5,000 Taliban prisoners as a token of goodwill. Yet he sits happily over lunch with a former Khost mayor who held the position under Ashraf Ghani’s government around a year ago.

The Khost governor — and Bergdahl exchangee — Omari, however, has met with a little more suspicion by the populace.

“The people of Khost are open-minded enough to give him a chance, but when the people here decide they don’t like someone, they will be gone,” a former public official warned.

Read Next:

Hollie McKay is a foreign correspondent, war crimes investigator, and best-selling author. She was an investigative and international affairs/war journalist for Fox News Digital for over 14 years where she focused on warfare, terrorism, and crimes against humanity; in 2021 she founded international geopolitical risk and social responsibility firm McKay Global. Her columns have been featured in publications including the Wall Street Journal and The Spectator Magazine. Her latest book, Only Cry for the Living: Memos From Inside the ISIS Battlefield, is now available.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.