The Berlin Blockade: How the Allies Kept an Entire City Fueled and Fed with Air Support

Berliners watching a C-54 land at Berlin Tempelhof Airport, 1948. Photo courtesy of U.S. Air Force.

The sun hovers above the old terminal like a melting coin, veining the sky with variegated shades of red and vermillion. In the east, the light has already begun to fade toward an inky purple. Looking across the massive expanse of Tempelhofer Feld, groups of people smoke their last cigarettes, stretch lazily as they pack up their picnics and barbecues, and collect their bottles for the recycling bins at the park’s entrance.

What used to be Berlin’s largest airport is now a cherished green space in the center of the city; a popular spot for rollerbladers, cyclists, kite-fliers, or anyone who just wants a brief sojourn from the concrete forest of apartment buildings. Its size and flatness also makes it a great spot for watching the sunset.

Like many areas in the German capital, this spot had a very different function 70 years prior. And, like many areas in the German capital, it was the focal point of a crisis that almost ended in a global catastrophe.

Nazi Germany Falls

Following the defeat of Germany in the second World War, which culminated in the Battle of Berlin, the city in question, as well as the country as a whole, was divided into four zones of occupation. The French, the British, the Americans, and the Russians each took a quadrant of Berlin and Germany under their administration in order to start rebuilding, claiming the territory roughly based on where their armies stood when Berlin fell and on the terms negotiated at the Potsdam Conference.

The initial plan was to consolidate all the zones of Germany into a unified and neutral state; however, the U.S. and its allies were secretly against this plan. In early 1948, the Soviets discovered that the other three nations were planning on combining their zones to build a new German state — West Germany — with the goal of creating a closely allied industrial Germany to aid in the rebuilding of Western Europe. To do this, one of the first hurdles would be to stabilize a wildly inflated economy and stymie a thriving black market of everyday goods. Germany’s currency, the Reichsmark, had been devalued by the Soviets through excessive printing and had to be replaced. The U.S. introduced a new currency, the Deutschmark, into the city, and it quickly became accepted in all four zones.

The Blockade Begins

Seeing the introduction of a new currency as a method of undermining Russia’s control of Germany, and fearing that the now-useless Reichsmark would flood the Soviet Occupation Zone, the Soviets implemented a blockade that prevented food, fuel, medicine, and other goods from reaching Berlin via road, rail, and water. On June 24, 1948, these transport links to Allied Berlin were severed permanently, effectively stranding the city without any form of resupply other than by air.

While this blockade was a major act of aggression from Soviet leaders, the Allies were reluctant to respond with military action, especially considering it would mean risking war over an enemy they had been fighting for the last five years. But with Allied-Occupied Berlin having only 36 days worth of food when the supply lines were cut, action had to be taken swiftly in order to keep the city fed and fueled.

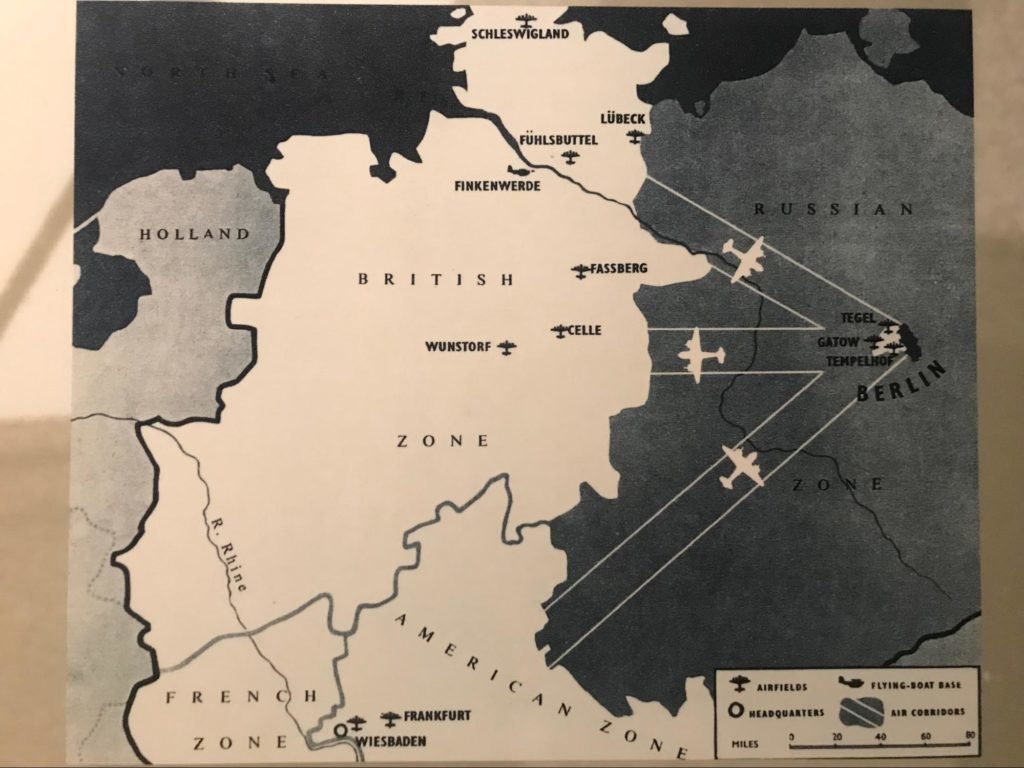

Since air corridors remained the only way in and out of the city, the Allies decided that this was the way to keep the city supplied. It would require a monumental amount of resources and manpower, which was no easy feat considering that Allied-Occupied Berlin’s population numbered some 2 million citizens.

An Impossible Feat

Today this impossible feat is memorialized at the Allied Museum and the Military History Museum at the former Gatow airport. Along with Tegel and Tempelhof, these were the only airports at which the Allies were allowed to land safely without harassment. Given the enormity of the task at hand, the Soviets were fairly certain that the Allies would have to capitulate, ask them for succor, and remove their forces from Berlin — or else let the city starve.

Hermann Hirsch, a member of the research staff at Gatow, confirmed that the Soviets were unprepared for a mission of this scale.

“Nothing like this had ever been attempted before,” Hirsch said in an interview with Coffee or Die. “And, really, when you think about it, they were right to be confident. A city of 2 million? That’s a staggering amount of mouths to feed, much less keep warm in the winter.”

In order to successfully sustain the city, the Allies would need around 4,500 tons of supplies every day. To accomplish this, American and British forces began a joint operation dubbed “Operation Vittles” immediately after the blockade began. On June 25, General Lucius D. Clay, administer of the U.S. Occupation Zone in Germany, gave the order to launch the operation.

The next day, 32 C-47s made for Berlin, carrying approximately 80 tons of food and medicine. Several days later the British sent their own aircraft, the idea being to sustain the city for approximately three weeks.

The blockade lasted just less than 12 months, with pilots from the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa aiding in the supply mission. The tonnage of supplies increased daily, surpassing the minimum threshold required on Aug. 12, 1948, and exceeding 8,000 tons by Feb. 26, 1949. In order to manage the massive influx of supplies, Berlin’s newest airport — Tegel — was constructed in less than three months, receiving the first planes on Nov. 5, 1948.

“It was an extraordinary effort,” Hirsch said. “By the end of the blockade, the Airlift was operating so smoothly that so many different planes were landing or taking off in Berlin every minute. Boeing B-29s, C-97s, Douglas C-47s and C-54s, Hastings 503 — every aircraft capable of carrying cargo was used.”

The Blockade Ends

On April 16, 1949, the American and British aircrews delivered almost 13,000 tons of coal, and it was clear that the blockade was not effective. On May 12, 1949, the Soviets conceded and reopened borders after negotiations with the Allies; the first trains and cars were allowed back into Allied-Occupied Germany. Concerned that the Soviets might reimplement the blockade as soon as their operation had ceased, the Western powers continued the airlift until Sept. 30, 1949.

This marked the first multinational skirmish of the Cold War, and soon after the states of West Germany and East Germany were established.

In total, the United States and Britain made 555,370 incoming and outgoing flights into Berlin before the borders opened, delivering 1,596,530 tons of coal and 538,016 tons of food. Despite the blockade, the Allies ultimately kept the city alive and free.

Martin Stokes is a contributing editor for Coffee or Die Magazine. He hails from Johannesburg, South Africa, but currently resides in Germany. He has numerous bylines that cover a variety of topics. He moved to Berlin in 2015 and, while writing for numerous publications, is working assiduously at broadening his repertoire of bad jokes.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.