Review: In ‘Drawing Fire,’ Bill Mauldin’s Cartoons Still Amuse, Still a Muse

Images courtesy of the Pritzker Military Museum & Library.

Compare the drawing in a Maximilian Uriarte Terminal Lance or a Steve Leonard Doctrine Man or a C.F. Grant Bohica Blues with the art in a cartoon by World War II legend Bill Mauldin.

You’ll notice a big difference in artistic style.

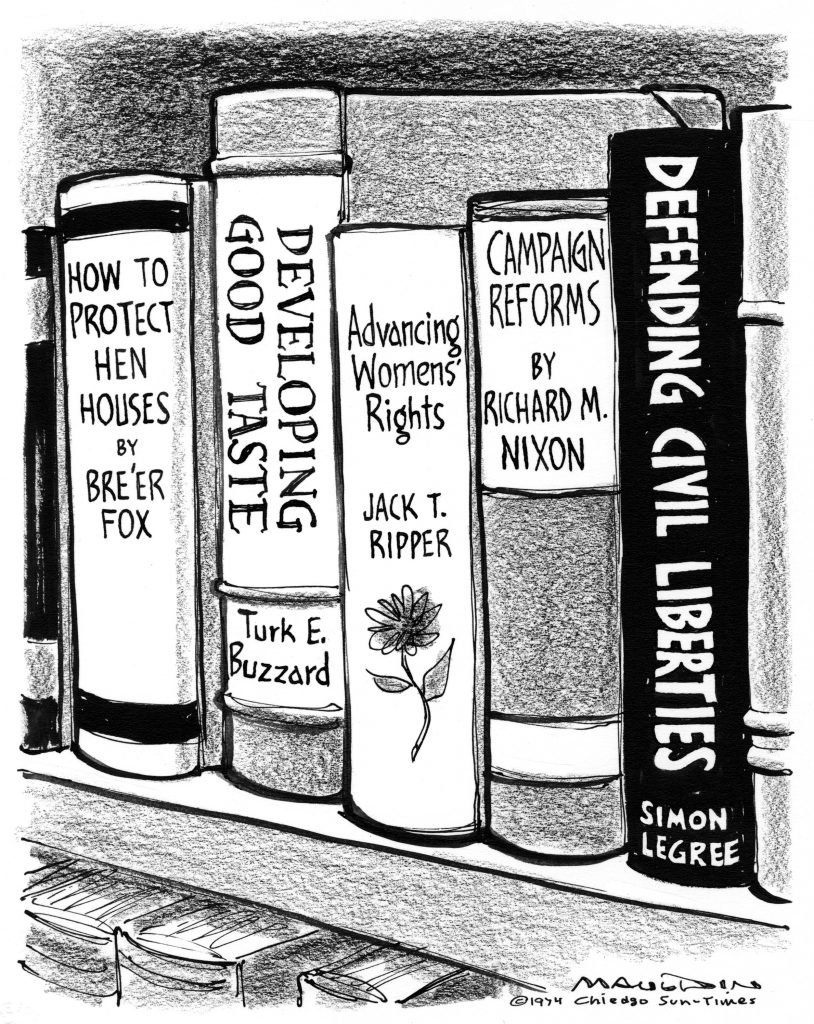

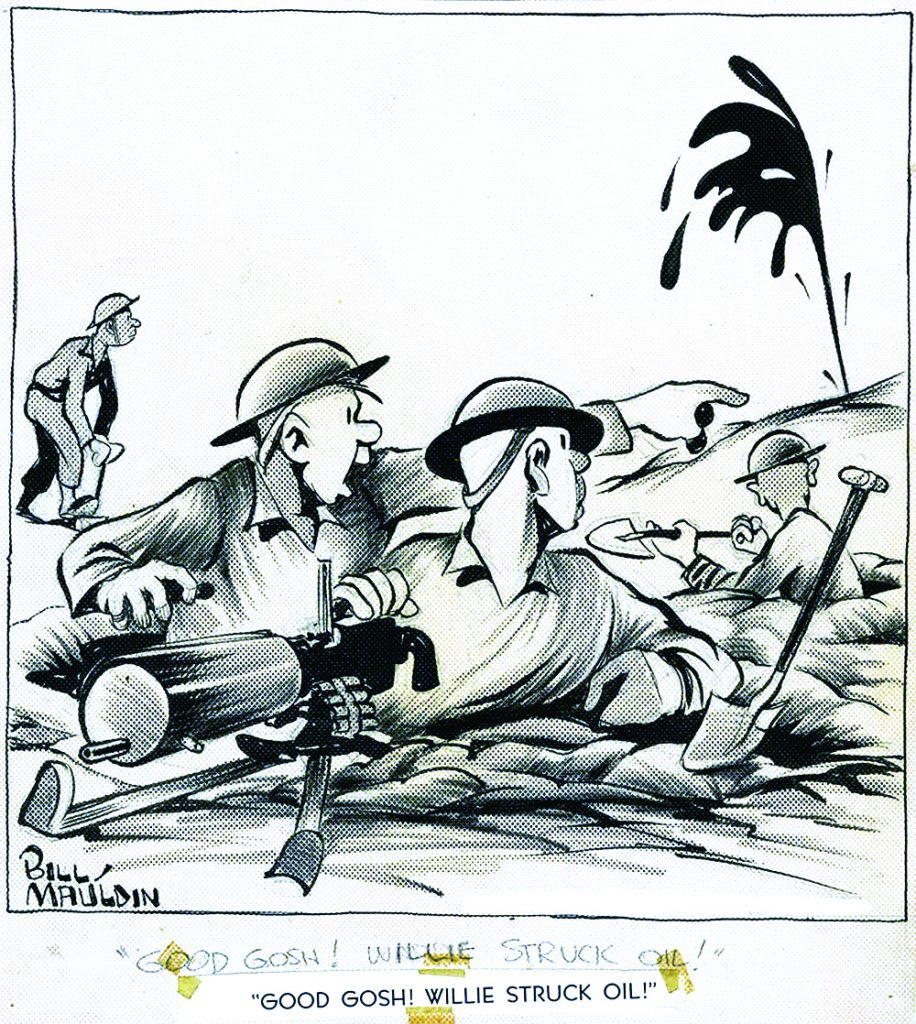

War-comics scholar Christina M. Knopf, a contributor to Drawing Fire: The Editorial Cartoons of Bill Mauldin, notes Mauldin’s realism, “heavy with lots of textures, shadows and shading.”

The “newer miltoon creators,” she says, “use more cartoonish styles” and softer lines. But the contemporary artists’ metaphorical edges often are hard and fall in line with muse Mauldin’s mighty pen.

Compare the message in a Uriarte and a Mauldin and you’ll probably notice little difference in theme — the gripes of the lesser stripes — the result of what Knopf refers to as Mauldin’s legacy: “The comedic elements of combat (its uncertainty, absurdity, and dissonance) and the ironic humorlessness of the military structure (its hierarchy, bureaucracy, and rigidity).”

Mauldin’s cartoons are, most importantly, funny and usually memorable. Poignant but pointed, and never maudlin. His unkempt characters Willie and Joe are tired but indefatigable.

“Just gimme a coupla aspirin,” Willie tells a medic. “I already got a Purple Heart.”

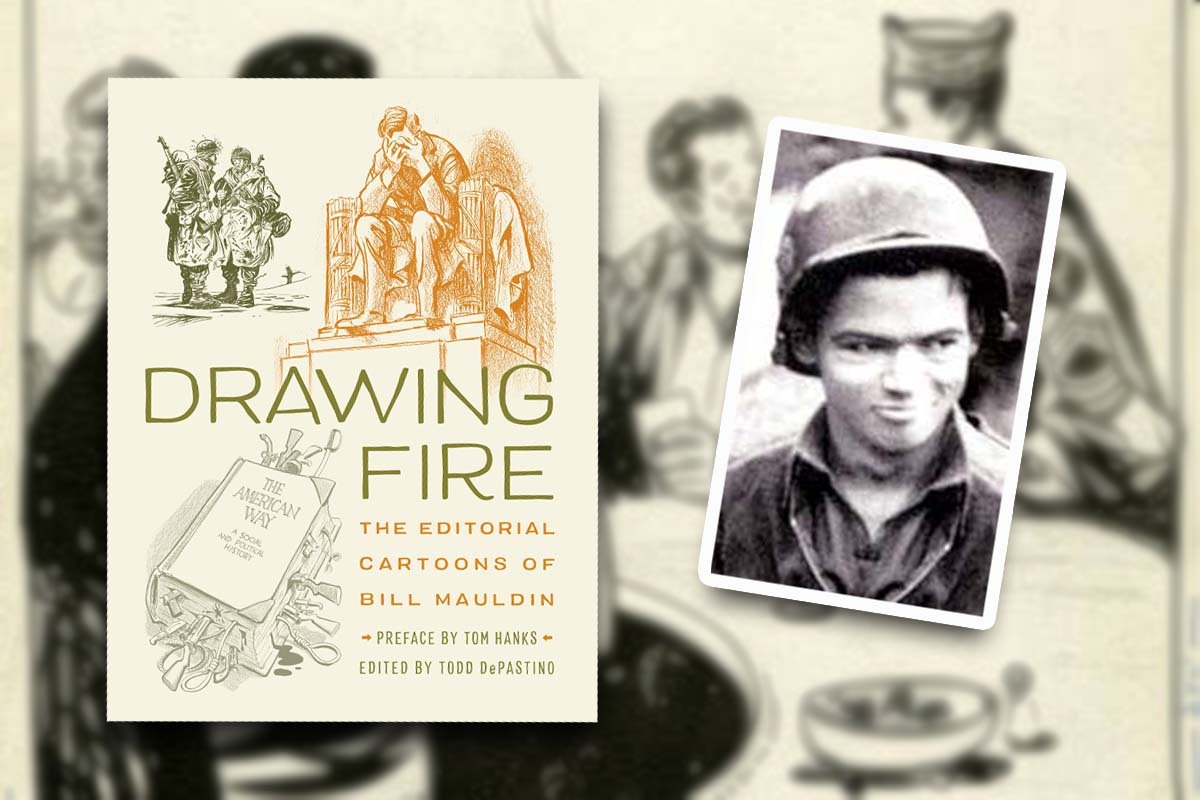

Drawing Fire, published by Pritzker Military Museum & Library, shows Mauldin’s sensitive hand and is a respectable commemoration of his longevity as a visual, societal observer.

The New Mexico native began publishing his work as Star Spangled Banter while in the 45th Infantry Division, 120th Quartermaster Regiment, as part of the Arizona National Guard in 1940. His editorial cartoons moved to Stars and Stripes in 1943 and were labeled Up Front.

In 1944 his work was syndicated in newspapers back in the States, and at age 23 he received his first Pulitzer Prize. The artist-writer-actor (he was in 1951’s The Red Badge of Courage with fellow veteran Audie Murphy) enjoyed a long career and left his Chicago Sun-Times drawing board in 1991.

Part of Maudlin’s appeal was his sense of the average Joe and his ability to portray him. He rejected “the mythic soldier of war propaganda, found in posters and comic books and movies,” Knopf says, and instead promoted “the unextraordinary citizen soldier.”

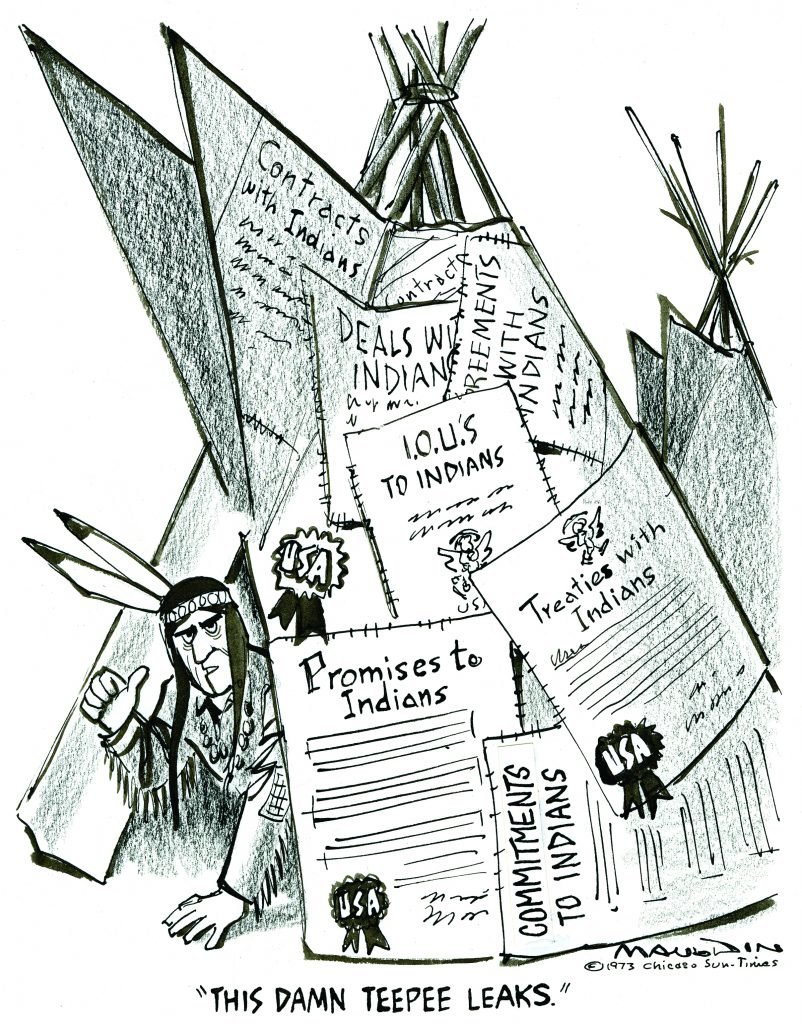

During World War II “almost all of Mauldin’s overseas cartoons focused on white infantrymen,” historian G. Kurt Piehler says. He “adhered to the War Department’s projection of a lily-white image of war.”

Mauldin’s later and more inclusive images reflect his backlash on bigotry. In his partially autobiographical 1947 collection, Back Home, he speaks “strongly about racial and religious discrimination.” The same year a commission advises President Harry S. Truman to desegregate the armed forces, and Mauldin depicts a full-bird officer with a Jim Crow on each shoulder.

Those “old eagles sure spoil that new uniform, colonel,” says the African American gentleman at the door of what appears to be a recruiting station.

The Pritzker library holds more than 4,500 of Mauldin’s cartoons, such as the Jim Crow example, and 150 images are in this collection edited by biographer Todd DePastino. Contributors include Tom Hanks, Tom Brokaw, and the library’s founder, retired Lt. Col. Jennifer N. Pritzker, Army National Guard, who calls Mauldin “the quintessential citizen-soldier.”

The many voices add valuable perspectives — and occasional duplication. Thrice you’re told that Gen. George S. Patton Jr. hated Mauldin’s work.

But the proof is in the clean design by Roberto de Vicq de Cumptich, who uses a military color palette of flat background hues such as khaki, olive drab, and gray. The background tints and shades help make the black-and-white drawings stand out.

Some of the reproductions show original compositions complete with crop marks, word changes, and pieces of cellophane tape. The notations and Mauldin’s process add a sense of immediacy, as though the works are ready to hit the press.

Get ready to see the works in person. The book celebrates the New Mexico native’s 100th birthday in 2021 and coincides with next year’s planned exhibit of his work at the Pritzker in Chicago. The show is scheduled to move to the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas.

Ike kept Mauldin’s commentary free from Army censorship — specifically by Patton. Perhaps Ike’s defense inspired Peanuts creator Charles Schulz, another World War II veteran, to mention Ike and Mauldin in his strip for Nov. 11, 1969.

In the Peanuts panel reproduced in the book, Snoopy announces that “it’s Veterans Day.” He dons his Ike jacket and heads away from the doghouse.

“I’ll probably go over to Bill Mauldin’s and drink root beer,” Snoopy advises — and you’ll wish you could go along.

Drawing Fire: The Editorial Cartoons of Bill Mauldin edited by Todd DePastino, Pritzker, 224 pages, $35

J. Ford Huffman has reviewed 400-plus books published during the Iraq and Afghanistan war era, mainly for Military Times, and he received the Military Reporters and Editors (MRE) 2018 award for commentary. He co-edited Marine Corps University Press’ The End of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (2012). When he is not reading a book or editing words or art, he is usually running, albeit slowly. So far: 48 marathons, including 15 Marine Corps races. Not that he keeps count. Huffman serves on the board of Student Veterans of America and the artist council of Armed Services Arts Partnership and has co-edited two ASAP anthologies. As a content and visual editor, he has advised newsrooms from Defense News to Dubai to Delhi and back.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.