A Complete List of Every Black Medal of Honor Recipient in U.S. History

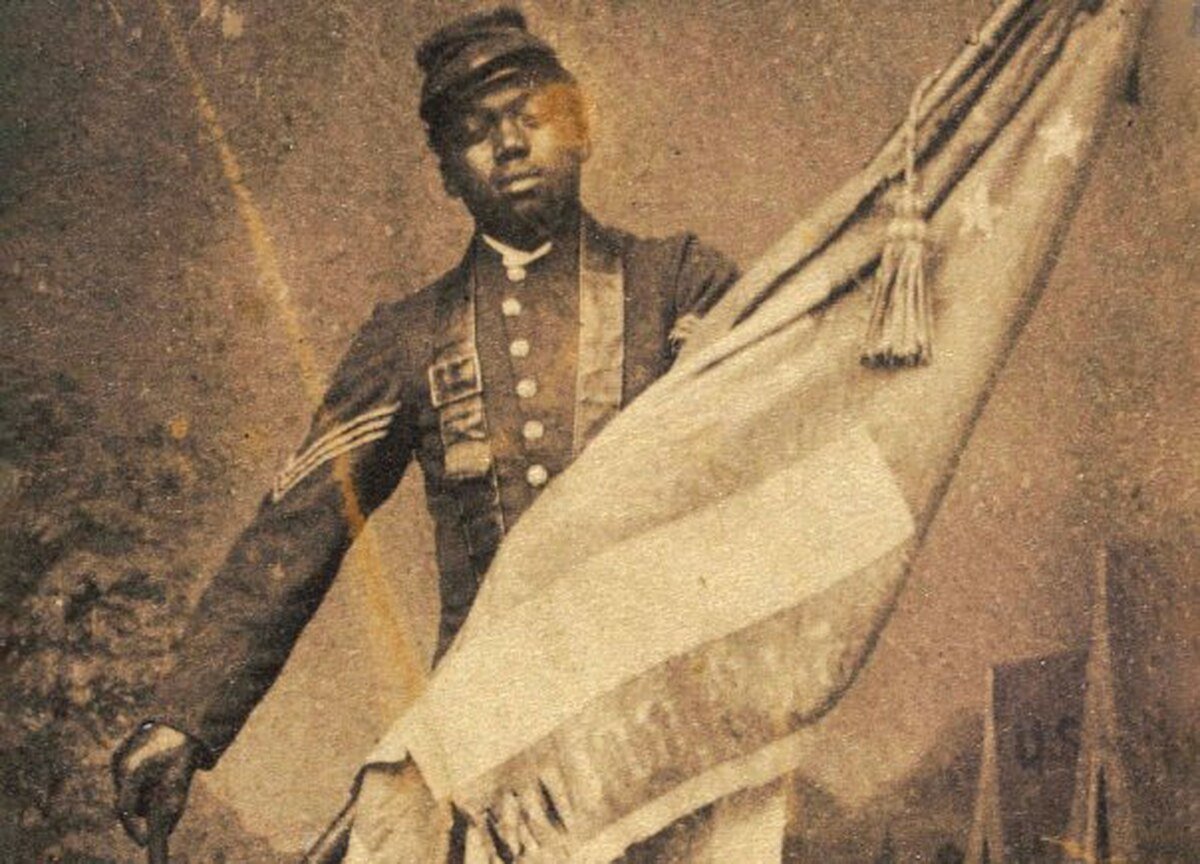

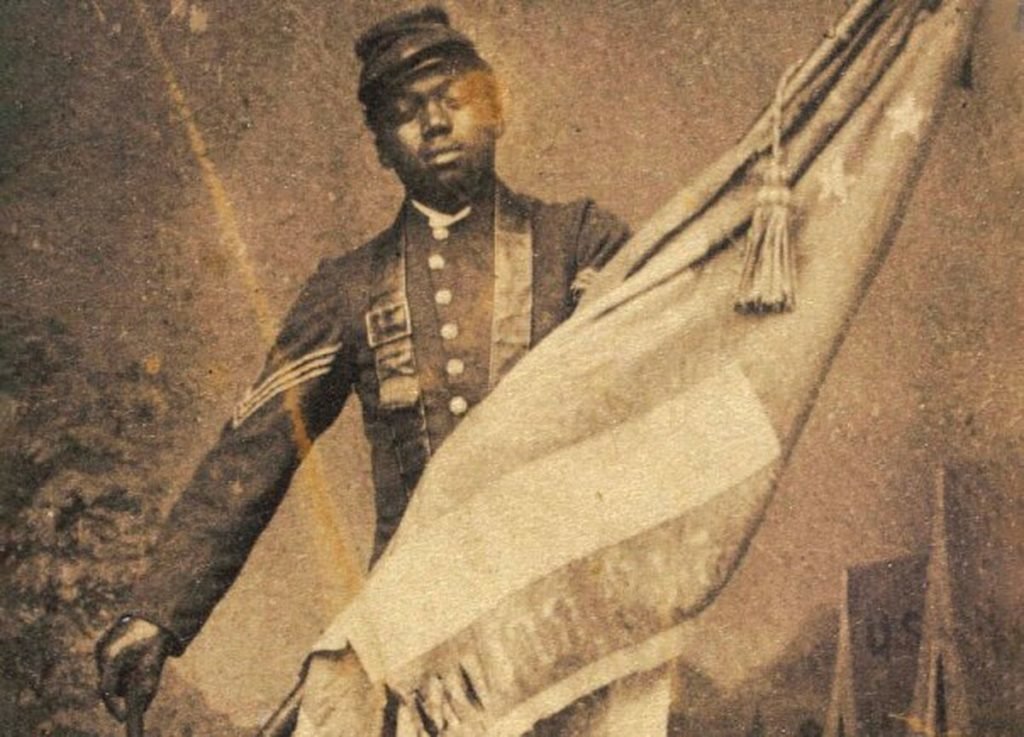

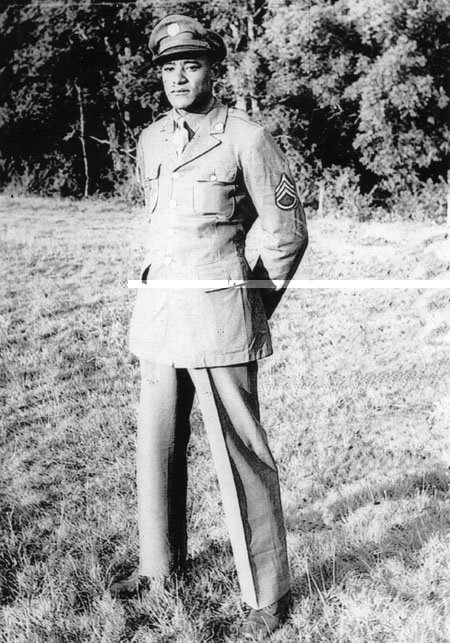

Army Sgt. William H. Carney. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Army.

During the month of February, we pay tribute to historic contributions made by African Americans. Throughout the history of the United States, racism and segregation were motivating factors for not properly recognizing worthy people for the merits they deserved. To this day, medals of valor are upgraded or reviewed, giving proper credit that was overlooked at the time they were presented.

Last year at Coffee or Die, we honored the 2nd Ranger Company and their battles during the Korean War; Odessa Madre, a flamboyant gangster from Washington, D.C. who earned the nom de guerre “Lady Al Capone”; and the notorious Harlem Hellfighters, a member of which appears on this very list. Only one African American, Robert Augustus Sweeney, received the Medal of Honor twice, and both were for life-saving actions during peacetime.

It’s worth noting that no black service members were awarded the MOH during or immediately after World War II. In 1997, President Bill Clinton upgraded seven Distinguished Service Cross awards to the Medal of Honor. Medals were awarded to two U.S. Army veterans from the all-black 24th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division during the Korean War, and the first black U.S. Marine earned the distinction during the Vietnam War. In total, there are 89 names on this distinguished list.

AMERICAN CIVIL WAR

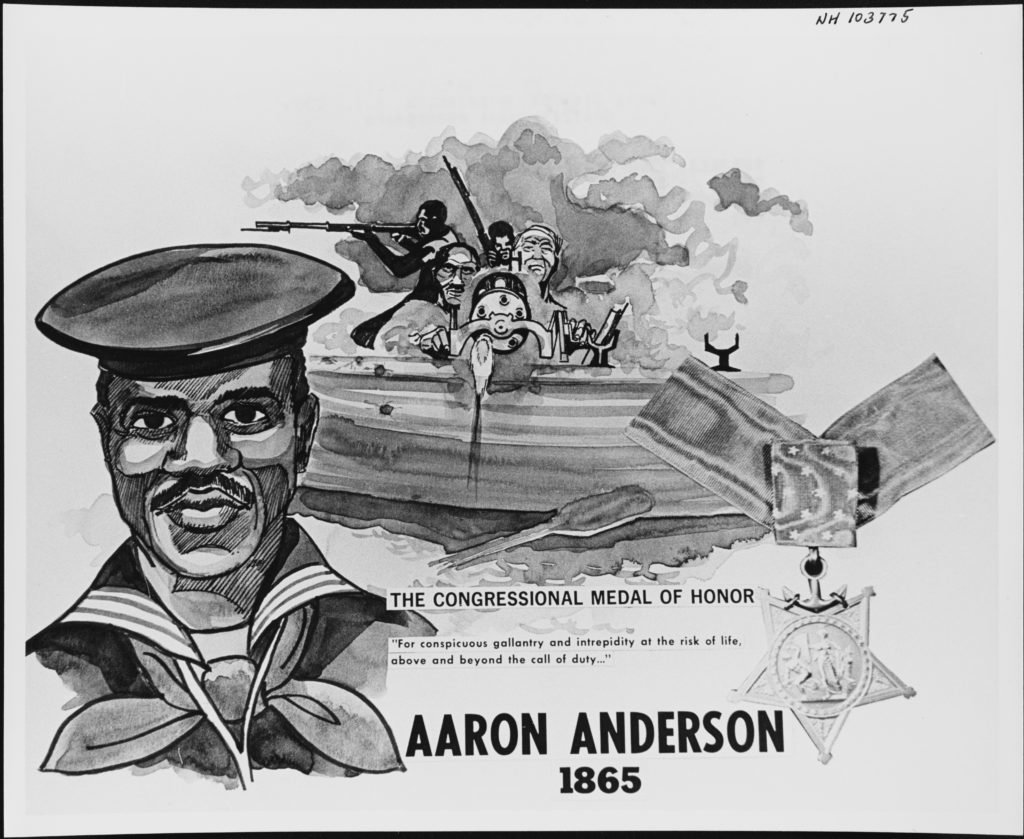

Landsman Aaron Anderson, U.S. Navy

Aaron Anderson’s name was written as Aaron Sanderson on the USS Wyandank manifest. He served as a landsman, and at 49 years old was credited with the heroic actions of “carrying out his duties courageously in the face of a devastating fire which cut away half the oars, pierced the launch in many places and cut the barrel off a musket being fired at the enemy.” For his actions during a boat expedition up Mattox Creek on the Maryland side of the Potomac River, he was awarded the MOH on March 17, 1865.

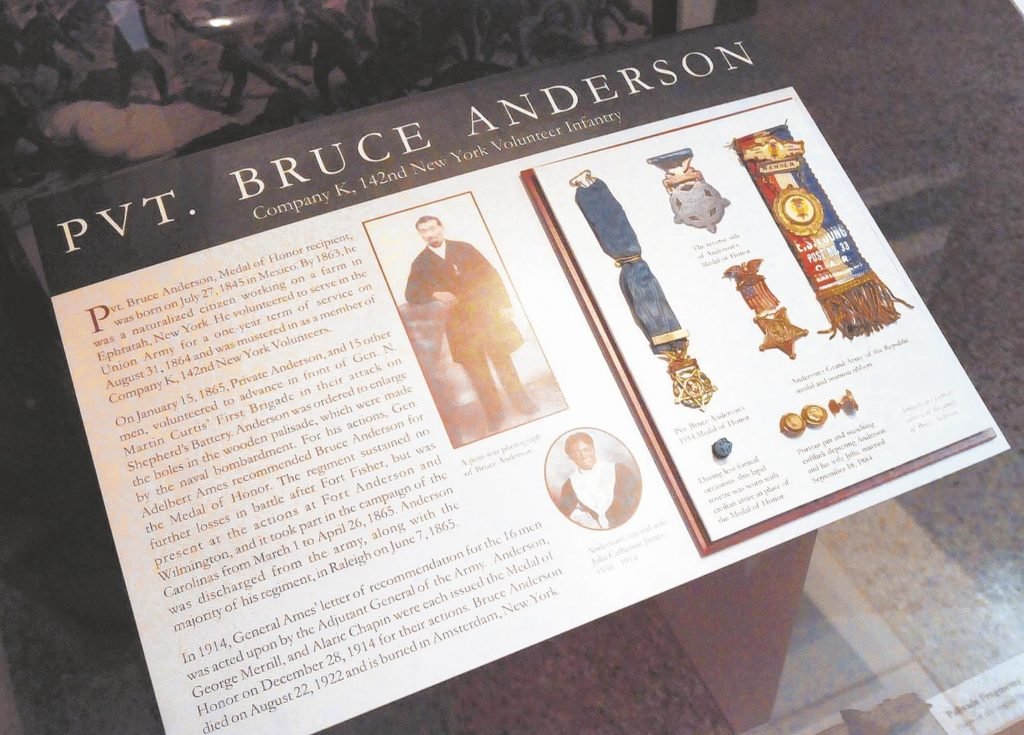

Private Bruce Anderson, U.S. Army

Bruce Anderson was born in Mexico on July 27, 1845. He immigrated to New York, where he worked on a farm, before volunteering to serve in the Union Army. He served with Company K, 142nd New York Volunteers, and on Jan. 15, 1865, he was a part of a 15-man advanced element responsible for clearing wooden palisades in front of Shepherd’s Battery. The all-volunteer force carried axes and equipment for the job while Confederate snipers suppressed with direct fire.

Anderson and 12 others cleared the way for Brigadier General N. Martin Curtis’ brigade, the main assault force on Fort Fisher. Major General Adelbert Ames recommended all 12 soldiers for the Medal of Honor, but the report was lost. Anderson and two others from the daring mission received the highest military honor 49 years later.

Sergeant William H. Barnes, U.S. Army

During the Civil War, unlike other U.S. wars, Americans received the MOH for heroism in fighting against other Americans. Private William H. Barnes, a 23-year-old farmer from Maryland, enlisted in the Union Army in 1864. Barnes served in the 38th U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) and led a historic charge in Virginia during The Battle of New Market Heights (Battle of Chaffin’s Farm), the first major battle led by African-American troops. Alongside the 4th, 5th, 6th and 36th USCT, his regiment assaulted five infantry regiments of Confederates.

Sergeant Major Christian Fleetwood, another Medal of Honor recipient, wrote of the first wave of the assault in his diary: “It was a deadly hailstorm of bullets sweeping men down as hail-stones sweep the leaves from trees. It was very evident that there was too much work cut out for our two regiments. We struggled through two lines of abatis, a few getting through the palisades, but it was sheer madness.”

On April 6, 1865, Barnes was awarded the MOH for his role “among the first to enter enemy works, although wounded.” Remarkably, of the 16 black MOH American Civil War recipients, 14 were awarded for their roles during this major battle. General Benjamin F. Butler also awarded the Butler Medal to 200 African-American soldiers, including Barnes, for their heroism during the battle. In 2013, a historical marker was placed in the Indianola Cemetery in Texas honoring Barnes’ memory.

First Sergeant Powhatan Beaty, U.S. Army

Powhatan Beaty had a name for theater, but he didn’t initially have the freedom to participate in it. His childhood in Richmond, Virginia, where he lived as a slave with little rights, was often violent. He later moved to the Cincinnati area and joined the Black Brigade, the unit responsible for digging trenches, clearing forests, building roads, and fortifying firing positions during the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm (also called Battle of New Market Heights). For 15 days of sustained manual labor, Union General Lew Wallace later commented, “When the history of Cincinnati during the past two weeks comes to be written up, it will be said that it was the spades (a then-popular derogatory term for black people) and not the guns that saved the city from attack by the Rebels.”

On Sept. 29, 1864, the Confederates eliminated several of Beaty’s men, including the flag bearer, as they retreated. Morale was low because all military officers were killed or wounded during the chaos. Beaty emboldened his troops by charging 600 yards through a hail of gunfire and explosions to recover the flag and took command of his regiment. After participating in 13 battles during the American Civil War, Beaty became a successful actor and playwright.

Seaman Robert Blake, U.S. Navy

On Christmas Day 1863, U.S. Navy sailor Robert Blake exemplified bravery as a rifle gun aboard the USS Marblehead gunboat as they engaged Confederate soldiers on John’s Island. His initial role wasn’t designated for combat, it was listed as Contraband, but after taking action against an attacking Confederate howitzer at Lageriville, the largest island in South Carolina, his commanders were impressed.

Lieutenant Commander Richard W. Meade, the commanding officer of the Marblehead, wrote in a report that “Robert Blake, a contraband, excited my admiration by the cool and brave manner in which he served the rifle gun.”

First Sergeant James H. Bronson, U.S. Army

First Sergeant James H. Bronson was a Pennsylvania native who worked as a barber before he joined Company D, 5th Regiment USCT. He acted as a leader and wrote of his wounds he sustained during battle. “I was struck on the calf of left leg by a glancing lick. I was lame for a few days pained much. I have really large bunch of veins on left leg and pain around my heart also numbness and weakness of left-side so much so that if I exert myself to any extent my suffering about my heart and left side are so that I fall to the ground.”

The official papers of his commendation cited that “all these gallant colored soldiers were left in [Bronson’s] command, all their company officers being killed or wounded, and led them gallantly and meritoriously through the day. For these services they have most honorable mention, and the commanding general will cause a special medal to be struck in honor of these gallant colored soldiers.”

Landsman William H. Brown, U.S. Navy

William H. Brown served in the U.S. Navy as a landsman. He worked aboard the USS Brooklyn, which was part of an 18-ship Union sea convoy during the Battle of Mobile Bay on Aug. 5, 1864. While Brown worked in the powder division, he braved intense enemy shell fire that wounded or killed several sailors on two separate occasions within the vicinity of his position.

Brown risked his life to keep the cannons on the gun deck supplied with fresh gunpowder and survived the successful battle. Four months later, on Dec. 31, 1864, he was awarded the MOH.

Shellboy/Landsman Wilson Brown & Landsman John Henry Lawson, U.S. Navy

Shellboy/Landsman Wilson Brown and Landsman John Henry Lawson were both awarded the MOH for working together against unbeatable odds during the Battle of Mobile Bay on Aug. 5, 1864. They worked on a shell whip crew, the team responsible for providing the cannons on the gun deck with ammunition. After a Confederate shell hit the USS Hartford, four of their six-man crew were killed. Brown and another sailor were thrown off their feet onto the deck below. Brown and Lawson were both knocked unconscious, and another man died beside them.

Lawson regained his wits first and assumed his duties at the reloading station; Brown joined him to get their guns back into action, despite several broken ribs.

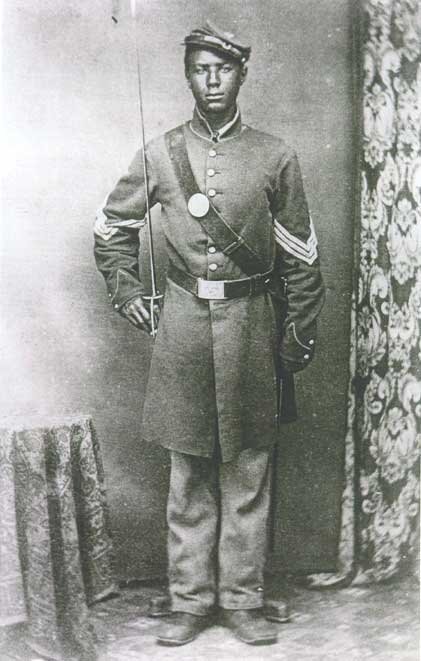

Sergeant William Harvey Carney Jr., U.S. Army

Sergeant William Harvey Carney is recognized as the first African-American MOH recipient to receive the award. Carney’s father, William, escaped from slavery in Norfolk, Virginia, by using the underground railroad and raised William Jr. in New Bedford, Massachusetts. In 1863, at 23 years old, Carney and 45 other volunteers joined a Union Massachusetts militia called the Morgan Guards, which later became Company C of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. Except for officers and senior noncommissioned officers, the unit was an all-black corps.

During the nighttime Battle of Fort Wagner on Morris Island, South Carolina, as the 54th Massachusetts assaulted the fort guarding the entrance of the Charleston, their troop’s flag bearer was hit by musket fire and a barrage of cannon shrapnel and dropped the flag. The flag’s colors shall never touch the ground, so Carney dropped his rifle, charged at a full-out sprint, grasped the flag, and continued onward despite being completely surrounded. He then hurled himself against a low protective wall of the fort. He later wrote, “The bullet I now carry in my body came whizzing like a mosquito, and I was shot. Not being prostrated by the shot, I continued my course, yet had not gone far before I was struck by a second shot.”

A soldier from the 100th New York joined him, and they retreated to their own lines. Carney sustained two bullet holes and two grazes in the arm and on the head. “Boys, the old flag never touched the ground,” he said before collapsing and receiving medical attention.

Corporal Decatur Dorsey, U.S. Army

Corporal Decatur Dorsey served as the flag bearer for the 39th United States Colored Infantry (USCT). Before he was a soldier, he was born a slave in Maryland. He served during “The Battle of the Crater,” so-called because Union soldiers breached Confederate lines and used explosives to blast a massive crater in the earth. This tactic aided the Confederates, however, as the crater became a key location for ambushes.

On Nov. 8, 1865, during a second attack on the fort, Dorsey and his troops engaged in hand-to-hand combat, capturing over 200 Confederate prisoners and two Confederate flags. For these actions, he was awarded the MOH.

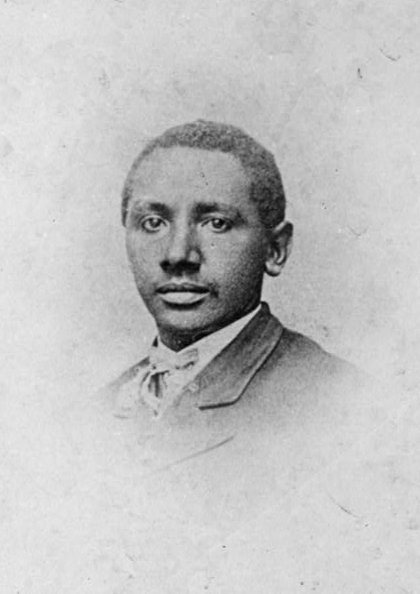

Sergeant Major Christian Fleetwood, Sergeant Alfred B. Hilton, & Private Charles Veale, U.S. Army

Sergeant Major Christian Fleetwood grew up in Baltimore as a free African-American and helped bring the first black-owned newspaper to South Carolina. When he entered service, he rose in rank to an NCO. During the Battle of New Market Heights (Battle of Chaffin’s Farm) on Sept. 29, 1864, Fleetwood “charged with the 6th at daylight and got used up…saved colors.” He described it as “a deadly hailstorm of bullets, sweeping men down as hailstones sweep the leaves from the trees.”

Sergeant Alfred B. Hilton also served with Fleetwood in the 4th Regiment USCT and was beside him during the battle. When he witnessed another flag bearer get hit by enemy fire, he grasped the second flag, one per hand, and encouraged his men to continue their assault. As Hilton became wounded during the fierce battle, Private Charles Veale took the regimental colors and Fleetwood took the national colors. For these dangerous but brave actions, all three were awarded Medals of Honor.

Private James Daniel Gardner & Corporal Miles James, U.S. Army

Private James Daniel Gardner and Corporal Miles James served in the same unit (36th USCT Regiment) during the same battle (Battle of Chaffin’s Farm) and were awarded for similar actions on the same day (Sept. 29, 1864). According to Gardner’s citation, he “rushed in advance of his brigade, shot a rebel officer who was on the parapet rallying his men, and then ran him through with his bayonet.”

Corporal Miles James lost his arm during the hellacious battle as the direct result of a field amputation. Remarkably, despite the loss of blood, he stood up, grabbed his pistol with his other hand, and encouraged his men to continue the assault. He was later promoted to sergeant and requested to remain in the Army. His request was approved, and he swapped his pistol for a sword. The 34-year-old received the MOH for his bravery and courage.

Sergeant James H. Harris & First Sergeant Edward Ratcliff, U.S. Army

Sergeant James H. Harris and First Sergeant Edward Ratcliff served together in the 38th USCT Regiment during the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm on Sept. 29, 1864. Edward Ratcliff’s family said he left his work in a field as a slave to walk from James City County, Virginia, to Yorktown to join the Union Army. A white officer in his command was wounded by enemy fire and Ratcliff assumed command. He was joined by Harris as they became the first enlisted soldiers to enter the fort in Richmond.

Private Thomas R. Hawkins & First Sergeant Alexander Kelly, U.S. Army

Private Thomas R. Hawkins and First Sergeant Alexander Kelly served in the same unit, the 6th USC Infantry and performed similar actions during different battles. Hawkins’ MOH citation from July 21, 1864, reads, “Rescue of regimental colors.” No further details are known other than that he participated alongside four black regiments at the Battle of Deep Bottom in one of the bloodiest battles in Virginia. General David B. Birney later said, “It was one of the most stirring and gallant affairs I have ever known.”

Twenty-three-year-old First Sergeant Alexander Kelly, who stood 5-foot-3.5, “gallantly seized the colors, which had fallen near the enemy’s lines of abatis, raised them and rallied the men at a time of confusion and in a place of the greatest danger.” Kelly was one of 14 black MOH recipients to earn the distinction during the Battle of Chaffin’s Farms at New Market Heights on Sept. 29, 1864.

Sergeant Major Milton M. Holland & First Sergeant Robert Pinn, U.S. Army

Bird Holland, a slave owner and former Secretary of State of the Republic of Texas, purchased slaves so he could free them. One of these slaves was Milton M. Holland, who, along with his three brothers, moved north. When the American Civil War began, Holland tried to enlist in the Union Army but was rejected. Eventually he served as a Sergeant Major in Company C in the 5th USCT in the infamous Battle of Chaffin Farms at Market Heights, Virginia. The battle had over 50 percent casualties of USCT troops. First Sergeant Robert Pinn, the 20-year-old former farmer served on the same battlefield as Milton while in Company I.

Their award citations are similar. Milton’s citation reads that he “took command of Company C, after all the officers had been killed or wounded, and gallantly led it.” Pinn took command of his own company under the same circumstances.

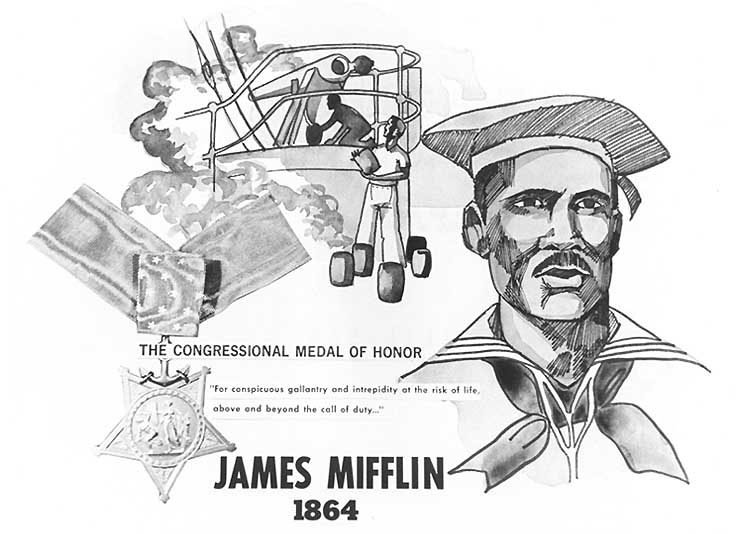

Engineer’s Cook James Mifflin, U.S. Navy

Not much is known about U.S. Navy Engineer’s Cook James Mifflin. He was born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1839 and served aboard the USS Brooklyn during the Battle of Mobile Bay, Alabama, on Aug. 5, 1864. His official MOH citation states that he was awarded for “remaining steadfast at his post on USS Brooklyn while enemy shells cleared his shipmates at the Battle of Mobile Bay, Alabama on 5 August 1864, which helped to result in damage at Fort Morgan and the surrender of CSS Tennessee.”

Seaman Joachim Pease, U.S. Navy

Seaman Joachim Pease was a New York native born in 1842. He served aboard the USS Kearsarge “when she destroyed the Alabama off Cherbourg, France, 19 June 1864. Acting as loader on the No. 2 gun during this bitter engagement, Seaman Pease exhibited marked coolness and good conduct and was highly recommended by the divisional officer for gallantry under fire.”

D.H. Sumer, acting master, later commented, “But among those showing still higher qualifications I am pleased to name … also Robert Strahan (captain top), first captain of No. 1 gun; James H. Lee, sponger, and Joachim Pease (colored seaman), loader of same gun. The conduct of the latter in battle fully sustained his reputation as one of the best men in the ship.”

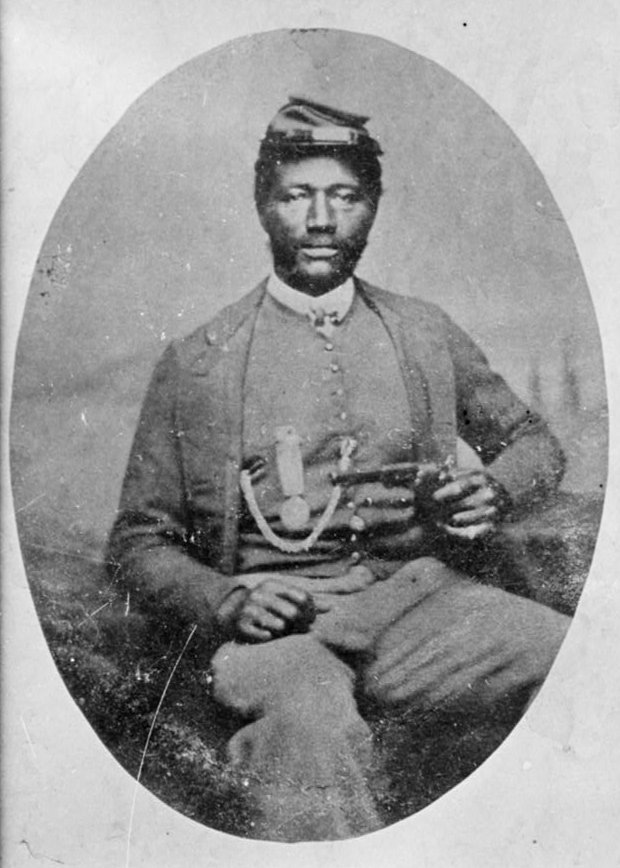

Corporal Andrew Jackson Smith, U.S. Army

Corporal Andrew Jackson Smith did not receive his Medal of Honor until Jan. 16, 2001, nearly 137 years after his heroic actions at the Battle of Honey Hill in South Carolina. He was a runaway slave before he chose to enlist in the 55th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. On Nov. 30, 1864, assisted by the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, Smith was caught in the crossfire as Confederate troops fired upon them in an open swamp. The flag bearer of the 55th was killed, and Smith swooped in to retrieve the regimental colors and inspire his troops to press on. He was nominated for the MOH in 1916, but poor documentation resulted in a delay before it was properly reviewed and awarded.

INDIAN WARS

Sergeant Thomas Boyne, U.S. Army

Sergeant Thomas Boyne’s life is surrounded by mystery. His MOH citation is brief enough to describe “bravery in action.” Boyne was born in Prince George County, Maryland, as a slave. He received a $10 bonus for joining the U.S. Colored Troops in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Following the war, Boyne served with the “Buffalo Soldiers” during the Indian Wars and was directly involved in two engagements at Mimbres Mountains and at Cuchillo Negro River in New Mexico in 1879. “I have seen him repeatedly in action,” noted an officer who recommended him for the award. “If any soldier ever deserved [the Medal of Honor], Sgt. Boyne does, and I hope he shall be so rewarded.”

Sergeant Benjamin Brown & Corporal Isaiah Mays, U.S. Army

Sergeant Benjamin Brown and Corporal Isaiah Mays served with the Buffalo Soldiers, the 24th Infantry, during the Indian Wars. On May 11, 1889, Mormon Outlaws attacked and ambushed U.S. Army Major Joseph Washington Wham’s caravan traveling from Fort Grant to Fort Thomas, Arizona, and stole $28,000 worth of gold and silver coins from a strongbox on his wagon. Eight Buffalo Soldiers on horseback, led by Brown, were assigned to protect him. As the Mormon Outlaws surprised them with accurate rifle fire, the Buffalo Soldiers retreated. According to Brown’s citation, “Although shot in the abdomen, in a fight between a paymaster’s escort and robbers, [he] did not leave the field until again wounded through both arms.”

Private James Young ran through more than 100 yards of outlaw gunfire to retrieve Brown and carry him behind cover. All eight members assigned to the escort were wounded and Mays, though shot in both of his legs, managed to crawl two miles to a nearby ranch for help. The Buffalo Soldiers estimated there were 12 bandits, and seven of them were later recognized because they didn’t cover their faces. Their carelessness was realized to not matter as seven of the bandits were acquitted of the shooting at trial.

Sergeant John Denny, U.S. Army

Sergeant Johnny Denny was dubbed “The Hero of B Troop” as he served as a “Buffalo Soldier” in the 9th Cavalry. He had a reputation as a brawler, and his antics had previously cost him rank. Denny served for 30 years in the U.S. Army, but his most notable achievement occurred on a “routine” horseback patrol. Denny and his patrol were searching for a rogue group of Apache Indians as they evaded into the New Mexican countryside. The Apaches set up a synchronized ambush and Private A. Freeland lay incapacitated in the open ground. Denny scrambled into the open, grabbed Freeland, and brought him to safety, thus saving his life during the ambush. Denny was awarded the MOH 12 years later in 1891.

Indian Scouts Pompey Factor, Issac Payne, & John Ward, U.S. Army

Pompey Factor, Isaac Payne, and John Ward were black Seminoles who were raised in either Mexico or Arkansas before they joined the U.S. Army as Indian scouts between 1870 and 1871. Black Seminoles were routinely treated poorly, but they accepted the roles in favor of land, pay, and rations. Factor served during the battles at Remolino, Mexico, and Kickapoo Springs, Texas.

On April 5, 1875, Lieutenant John L. Bullis learned of an attack on a stagecoach by a group of 25 Indians. He handpicked Factor, Payne, and Ward, and the small number wasn’t an outrageous proposition to Bullis because black Seminole scouts were respected as frontiersman. It took the scouts 21 days to track the Indian raiders across West Texas until they spotted them at Pecos River at Eagle Nest Crossing on April 26, 1875. They launched a surprise attack against the Indians, but during the chaos, Bullis was thrown off his horse. The remaining three rescued Bullis, fought off more than 25 hostiles, and escaped with their lives. Bullie recommended all three for the MOH.

Corporal Clinton Greaves, U.S. Army

Clinton Greaves likely grew up in slavery and moved to Virginia following the conclusion of the American Civil War. He enlisted in the Army and acquired the rank of corporal in the 9th Cavalry Regiment. He was a Buffalo Soldier tasked with apprehending 40 to 50 rogue Apaches in New Mexico. He and a small detachment pursued them into the Florida Mountains, but they were surrounded. His MOH citation for his actions on Jan. 24, 1877 reads, “Cpl. Greaves in the center of the savage hand-to-hand fighting, managed to shoot and bash a gap through the swarming Apaches, permitting his companions to break free.”

Sergeant Henry Johnson, U.S. Army

Two African-American soldiers named Henry Johnson have received the Medal of Honor. During the Indian Wars, Henry Johnson served in the U.S. Army’s 9th Cavalry, commonly referred to as the Buffalo Soldiers by the American Indian tribes they pursued. From Oct. 2 to 5, 1879, Johnson “voluntarily left fortified shelter and under heavy fire at close range made the rounds of the pits to instruct the guards, fought his way to the creek and back to bring water to the wounded.”

On Sept. 22, 1890, he was awarded the MOH for his actions during the Battle of Milk Creek fighting against the Ute nation in Colorado.

First Sergeant George Jordan & Sergeant Thomas Shaw, U.S. Army

George Jordan enlisted in the U.S. Army and rose to the rank of first sergeant in a 26 year career with the Buffalo Soldiers. During his career, he also sought education and learned to read and write. Thomas Shaw was was born into slavery in Covington, Kentucky. He escaped to join the U.S. Army and served in the 9th Cavalry Regiment. They fought against the Apaches and the Sioux tribes that harassed settlers and ranchers in New Mexico.

The citations for their individual actions toward their battle reads: “While commanding a detachment of 25 men at Fort Tularosa, New Mexico, repulsed a force of more than 100 Indians. At Carrizo Canyon, New Mexico, while commanding the right of a detachment of 19 men, on 12 August 1881, he stubbornly held his ground in an extremely exposed position and gallantly forced back a much superior number of the enemy, preventing them from surrounding the command.”

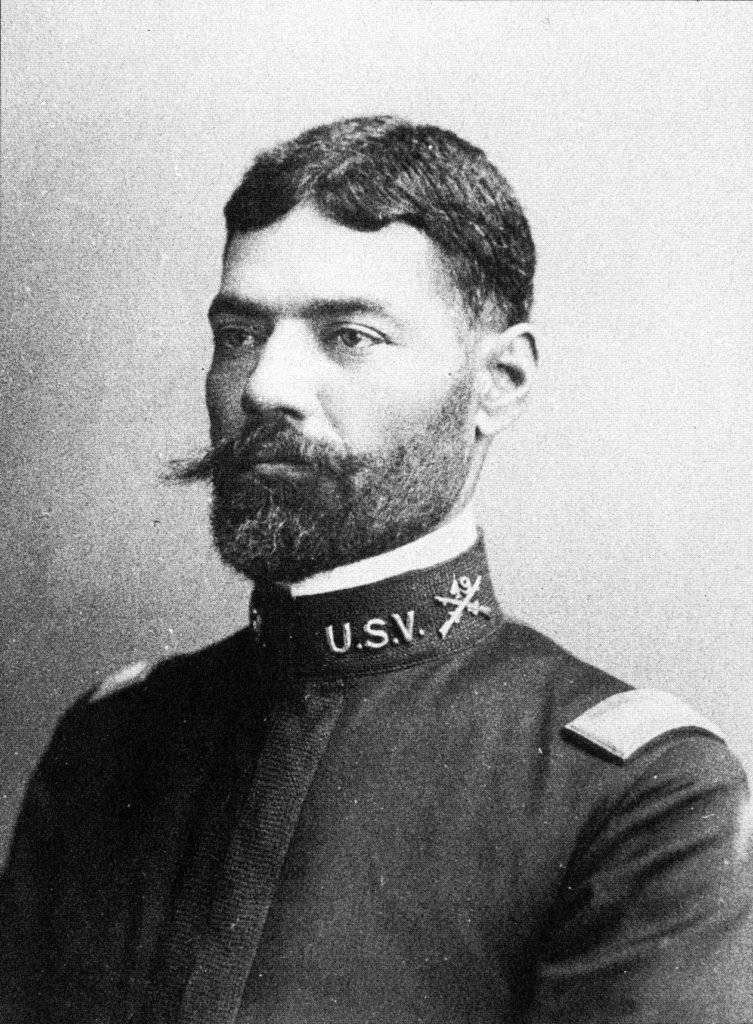

Sergeant William McBryar, U.S. Army

William McBryar received the Medal of Honor when he was a sergeant in the U.S. Army’s 10th Cavalry. The 9th and 10th Cavalry regiments were both nicknamed the Buffalo Soldiers. His award citation indicates that he was honored for his “coolness, bravery and marksmanship” while his 10th Cavalry troop was in pursuit of Apache warriors” during the Cherry Creek Campaign in the Arizona Territory in 1890. McBryar’s career didn’t stop there — he received a commission for the rank of lieutenant and served during the Spanish-American War and the Phillippine Insurrection. He also worked as an Arlington National Cemetery watchman following his time in the Army.

At 73 years old, McBryar graduated from Tennessee State Agriculture & Industrial College (now Tennessee State University) in 1933 and wrote for the school’s newspaper “The Bulletin.”

Private Adam Paine, U.S. Army

When historians first hear Adam Paine’s name, the Medal of Honor recipient’s valor isn’t the first thing to come to mind. Paine infamously found himself on the wrong end of a double-barreled shotgun fired from fellow Medal of Honor recipient Claron Windus. It is the only time in history when one MOH recipient killed another MOH recipient. Private Paine served in the Indian Scouts, where he excelled. He was a black Seminole and was recognized for his actions between Sept. 26 and 27, 1874, when he “rendered invaluable service to Col. R. S. Mackenzie, 4th U.S. Cavalry, during this engagement,” according to the citation.

Paine’s killing occurred after both men left the military. Windus was the deputy sheriff for Kinney County in Brackettville, Texas. Paine became an outlaw when he murdered a cavalryman in Brownsville, Texas. The lawmen learned that Paine would be at a New Year’s Eve party, and they planned to apprehend him there. Three MOH recipients were in attendance: Paine, Windus, and fellow Indian Scout Isaac Payne. During the confrontation, Windus killed Paine and another man with his shotgun.

Sergeant Emanuel Stance, U.S. Army

Sergeant Emanuel Stance became the first Buffalo Soldier to earn the Medal of Honor. In May 1870, during a hostage rescue mission in Kickapoo Springs, Texas, Stance rescued captive William Lehmann. He later described his fight against the Kickapoo, “I immediately attacked them by charging them. They tried hard to make a stand to get their herd of horses off, but I set the Spencers to talking and whistling about their ears so lively that they broke in confusion and fled to the hills, leaving us their herd of five horses. Resuming the march towards Camp, they skirmished along my left flank to the eight mile water hole, evidently being determined to take the stock. I turned my little command loose on them at this place, and after a few volleys they left me to continue my march in peace. I reached camp at 2 pm of the 21st with 15 head of horses captured from the Indians.”

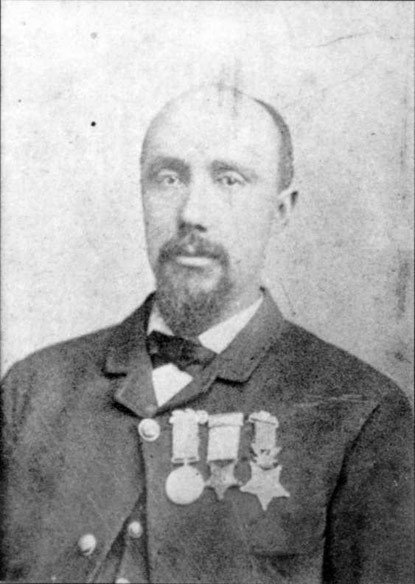

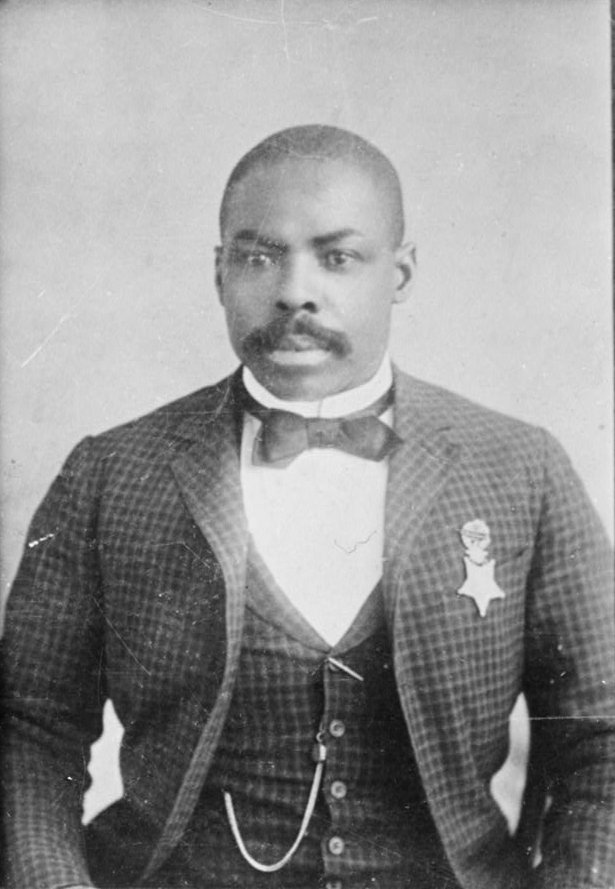

Private Augustus Walley & First Sergeant Moses Williams, U.S. Army

![Ordnance Sergeant Moses Williams, U.S. Army [Medal of Honor] Unknown author - U.S. National Archives](https://cdn.builder.io/api/v1/image/assets%2F068e3e7817cb4351b71538fa2436cbc2%2F696dad78eb6d47b48161a55ae7a97c3c)

Walley, Augustus, and another soldier came to their rescue. When another Buffalo Soldier’s horse became confused and charged toward a gathering of Apaches, the soldier fell off to avoid being killed. Walley ran from cover, picked up the soldier, and carried him back to safety. Walley, Williams, and Lieutenant George Burnett were awarded Medals of Honor. In 1886, Williams became one of the first Ordnance Sergeants in the U.S. Army and was also responsible for large coastal gun emplacements along the West Coast. He retired after 32 years of honorable service.

Corporal William Othello Wilson, U.S. Army

Corporal William Othello Wilson served with the 9th Cavalry Regiment, known as the Buffalo Soldiers during the Indian Wars. On Dec. 30, 1890, Wilson volunteered to carry a message for help after American Indians from the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota attacked a supply train. He rode on his horse for more than two miles to the Pine River Agency while Indians chased and fired upon him. For these actions, the 22-year-old Maryland native was awarded the Medal of Honor, the last honor for an African-American soldier during the Indian Wars.

Sergeant Brent Woods, U.S. Army

Brent Woods was raised as a slave in Kentucky and joined the U.S. Army serving in the well-known 9th Cavalry Regiment, or Buffalo Soldiers. On Aug. 19, 1881, Woods and his patrol were ambushed in the New Mexico Gavilan Canyon by Apache Indians. The battalion’s commander was killed, and Woods took command and successfully saved the lives of his men from certain injury or death. He received the Medal of Honor in 1894 and was buried with full military honors nearly 100 years later in 1984.

SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR

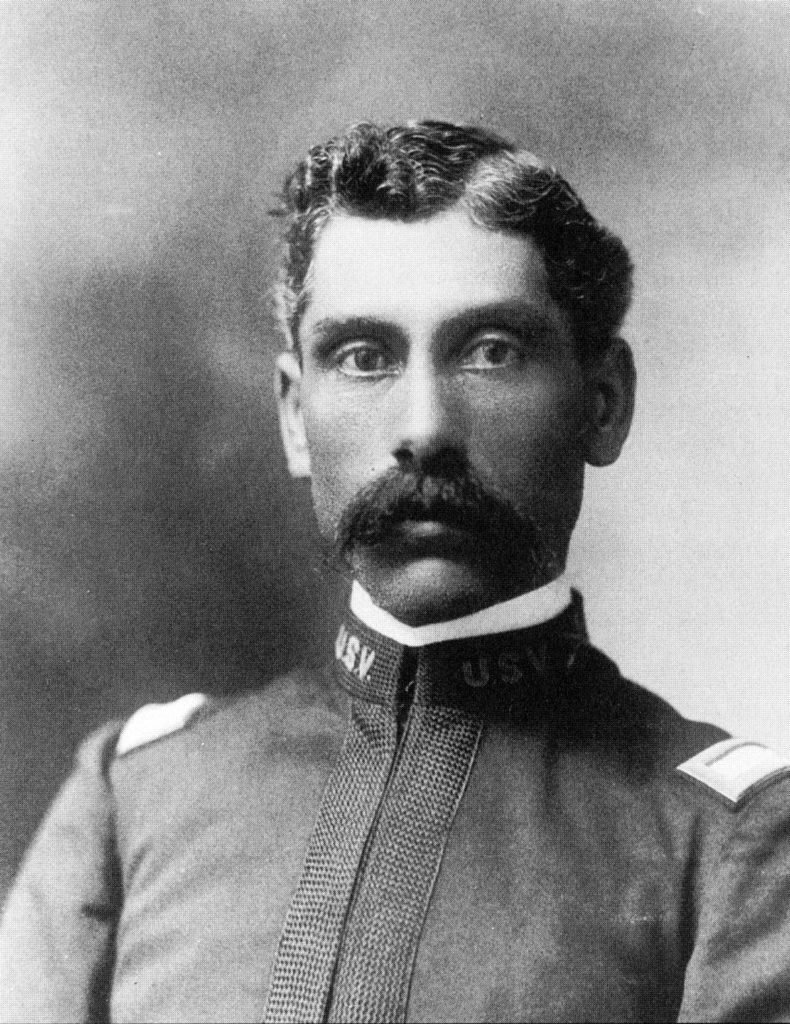

Sergeant Major Edward L. Baker Jr., U.S. Army

Sergeant Major Edward Lee Baker Jr. served with the U.S. Army’s all-black 10th Cavalry Division during the Spanish-American War. On July 1, 1898, Baker left cover while under intense enemy fire and rescued a wounded teammate from drowning. The Cincinnati native served 20 years in the U.S. Army and was awarded the MOH for his actions in Santiago, Cuba, during an assault on San Juan Hill.

Private Dennis Bell, Private Fitz Lee, Corporal George Wanton, & Sergeant William H. Thompkins, U.S. Army

Dennis Bell was a 31-year-old coal miner from Washington when he joined the all-black 10th Cavalry Division in the U.S. Army, commonly referred to as the Buffalo Soldiers. Private Bell, alongside Private Fitz Lee, a 32-year-old Virginia native; Corporal George Wanton, a 32-year-old from New Jersey; and Sergeant William H. Thompkins, volunteered for a mission they didn’t expect to return from. Their mission was to wade into hostile territory to rescue their partner force: six wounded Cuban soldiers who almost certainly would have perished if not for the Buffalo Soldiers.

Although previous rescue attempts had been called off, on June 30, 1898, in the Cuban town of Tayabacoa, these four men successfully rescued the Cuban soldiers, pulling them from the water despite receiving direct fire. For the fearless dedication to complete the mission, the MOH was individually awarded to Bell, Lee, Wanton, and Thompkins.

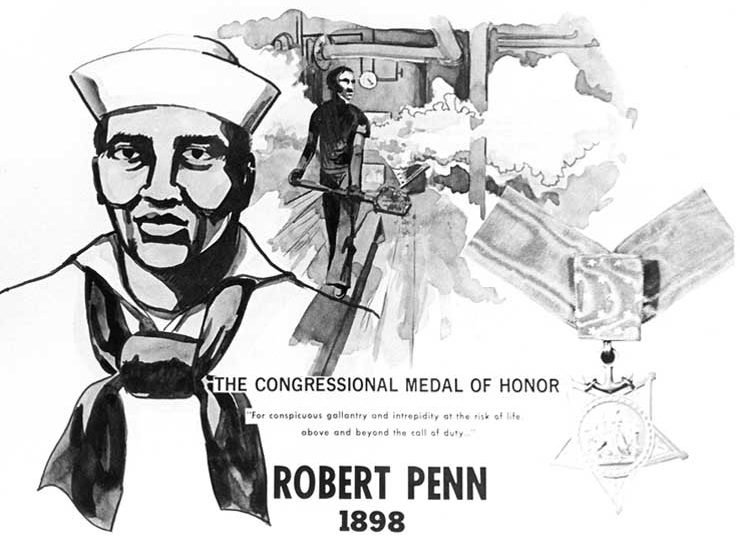

Fireman First Class Robert Penn, U.S. Navy

Fireman First Class Robert Penn was a 26-year-old sailor serving aboard the USS Iowa when a fire accident erupted on the vessel off the coast of Santiago, Cuba. Penn faced serious danger as he stood on a plank over boiling water to put out the flames. If Penn hadn’t acted, the fire would have spread to the rest of the ship and endangered more of the ship’s crew. For his actions on July 20, 1898, Penn was awarded the Medal of Honor.

WORLD WAR I

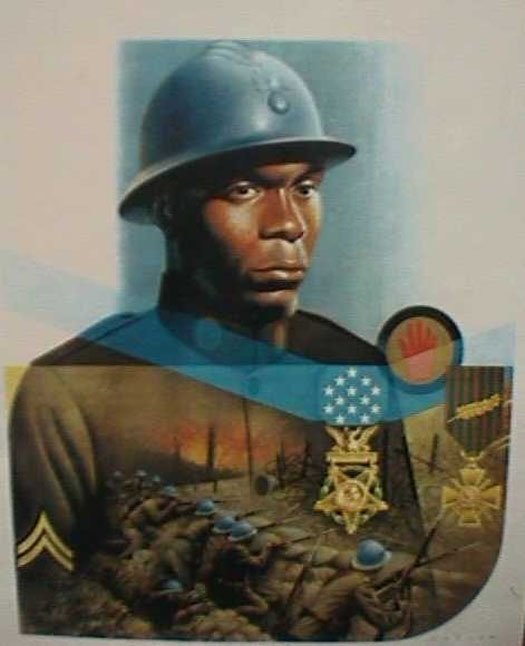

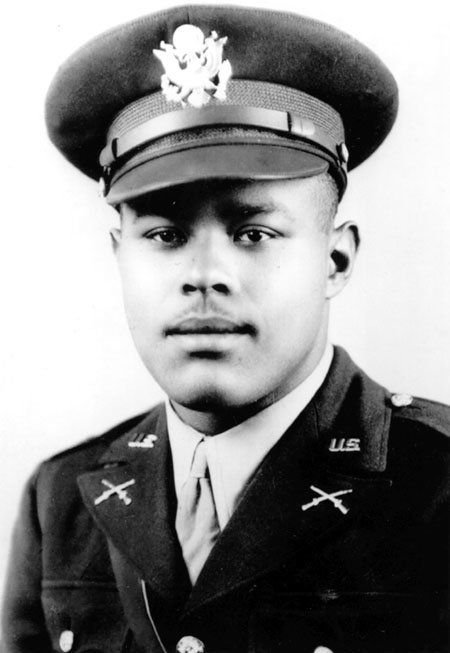

Corporal Freddie Stowers, U.S. Army

Freddie Stowers initially received the Distinguished Service Cross, but it was upgraded to the Medal of Honor in 1991. Stowers served in the 93rd Division under the French command because the U.S. wasn’t using African-American troops in the infantry at that time. Two weeks into the Meuse-Argonne offensive, Stowers and his teammates rushed Hill 188, a fortified German position. German troops appeared out of the trenches with their hands raised, but it was a feign surrender to draw them in. Stowers’ leadership was cut down by an aggressive machine gun position, and Stowers took command and led his troops to overtake the position.

His teammates pursued a second entrenchment, and he moved to coordinate further attacks. He was struck once but continued until he was struck by gunfire a second time. On the ground, fighting for his life, Stowers encouraged his troops to keep fighting until his final breath. He died on the battlefield at the age of 22 and was buried in the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery in France.

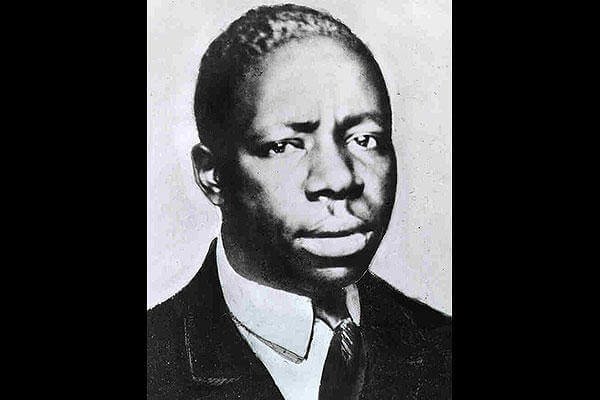

Private William Henry Johnson, U.S. Army

Henry Johnson may be the most recognized recipient on this list because of his role serving in the Harlem Hellfighters during World War I. Theodore Roosevelt Jr. called Johnson “one of the five bravest soldiers during the war.” The Germans nicknamed him “Black Death,” and when he returned to New York in a welcoming home parade, spectators screamed his nickname as loud as they could muster. As a Harlem Hellfighter, he and teammate Needham Roberts repelled a raiding party of 24 Germans in the dead of night using carbines, hand grenades, and their own two hands.

During the assault, the Germans wounded Roberts and tried to capture him alive. Johnson’s carbine jammed and he was armed only with a bolo knife. He attacked the remaining Germans in hand-to-hand combat and prevented them from taking Roberts as their prisoner of war (POW). They became the first two Americans — and first two privates — to earn the the Croix de Guerre, France’s highest honor. Johnson was awarded the MOH for single-handedly defeating a swath of German soldiers with a bolo knife as they tried to capture the wounded Roberts.

WORLD WAR II

Second Lieutenant Vernon Baker, U.S. Army

Between April 5 and 6, 1945, Vernon Baker was assigned to Company C, 370th Infantry Regiment, 92d Infantry Division, serving near Viareggio, Italy. In mountainous terrain, he fearlessly led his team in an assault against several entrenched enemy positions. He single-handedly destroyed an enemy machine gun position after he crawled within feet of it and killed three Germans. He then advanced alone to kill two more Germans manning an observation post.

The momentum shifted in favor of the Americans, and Baker was then joined by his squad who aided him in eliminating two more machine gun positions. When the dust settled, he helped provide resources to evacuate the wounded. The following night, as combat operations ensued, Baker guided his team through a minefield under intensive fire. In 1997, he attended a ceremony at the White House where his Distinguished Service Cross was upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

Staff Sergeant Edward A. Carter Jr., U.S. Army

Edward A. Carter Jr. was the son of missionary parents. Before he became an NCO in the U.S. Army, he had military experience as a 15-year-old lieutenant in the Chinese Army. It was a short-lived term of service, but he also became fluent in Manadarin Chinese, Hindu, and German while living in Shanghai. He fought in the Spanish Civil War with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, a communist force that ultimately forced him to flee to France and then later to the United States.

He enlisted in the U.S. Army on Sept. 6, 1941, but because of his service in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and Chinese Army, a counterintelligence surveillance team followed his every move. During World War II, he was stripped of his rank and assumed the role as a private because “black men don’t lead white soldiers.”

However, Captain Floyd Vanderhoff and General George Patton noticed his leadership abilities, restored his rank to staff sergeant, and made him an infantry squad leader. Patton appointed Carter as one of his personal bodyguards in the “Mystery Division.”

On March 23, 1945, Carter was in a tank as his convoy was driving through a field. The Germans launched a vicious ambush and his tank was rendered useless. His four-man tank squad ran for cover because the tank was on fire. Two of them were killed, one was seriously wounded, and Carter was the only one to make it to cover. He was wounded five times. Eight Germans flanked him and tried to take him alive, but he killed six of them. He used the remaining two as human shields to run to his unit. His two POWs gave up valuable intelligence.

In 1999, 36 years after his death, Carter’s Distinguished Service Cross was upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

First Lieutenant John R. Fox, U.S. Army

John Fox grew up in Cincinnati, Ohio, and attended Wilberforce University where he participated in Army ROTC. When he graduated in 1940, he received his commission as a second lieutenant. During World War II, Fox served in the 598th Field Artillery Battalion, 366th Infantry Regiment, 92nd Infantry Division (Colored) — the “Buffalo Soldiers” of the war. On Dec. 26, 1944, Fox, now a first lieutenant, called an artillery strike onto his own position to save the lives of his teammates.

A strong German force entered the Italian town of Sommocolonia on Christmas night dressed in civilian clothes to mask their intentions. The next day, the Germans were in control. All American soldiers abandoned their positions, but Fox and a few other soldiers stayed behind to act as a forward observer party. From the second floor, Fox directed artillery with devastating accuracy. The Germans were a numerically superior force and, in order for Fox’s team to make it out alive, Fox directed all 75 artillery guns to fire on his own position. The aftermath saw Fox dead surrounded by more than 100 dead German soldiers. Fox was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross in 1982, which was upgraded to the Medal of Honor in 1997.

Private First Class Willy F. James Jr., U.S. Army

Private First Class Willy F. James Jr. was assigned to the U.S. Army’s 413th Infantry Regiment, 104th Infantry Division. A native of Kansas City, Missouri, he led his squad near Lippoldsberg, Germany. According to his award citation from April 7, 1945: “As lead scout during a maneuver to secure and expand a vital bridgehead, Private First Class James was the first to draw enemy fire. He was pinned down for over an hour, during which time he observed enemy positions in detail. Returning to his platoon, he assisted in working out a new plan of maneuver. He then led a squad in the assault, accurately designating targets as he advanced, until he was killed by enemy machine gun fire while going to the aid of his fatally wounded platoon leader.”

Staff Sergeant Ruben Rivers, U.S. Army

Staff Sergeant Ruben Rivers grew up in Tecumseh, Oklahoma, with 11 brothers and sisters. Before he joined the U.S. Army’s 761st Tank Battalion, commonly known as the Black Panthers, Rivers worked on the railroad. During World War II, he was twice decorated for valor, both times posthumously. The first came on Nov. 8, 1944, near Vic-sur-Seille, France, when Germans blocked their tank convoy with a fallen tree and surrounded it with land mines. Rivers recognized an ambush was imminent and repositioned his tank, saving several lives in the process. He was awarded the Silver Star.

His Medal of Honor action came only days later. “For extraordinary heroism in action during 15-19 November 1944, toward Guebling, France. Though severely wounded in the leg, Sergeant Rivers refused medical treatment and evacuation, took command of another tank, and advanced with his company in Guebling the next day. Repeatedly refusing evacuation, Sergeant Rivers continued to direct his tank’s fire at enemy positions through the morning of 19 November 1944. At dawn, Company A’s tanks began to advance towards Bougaktroff, but were stopped by enemy fire. Sergeant Rivers, joined by another tank, opened fire on the enemy tanks, covering company A as they withdrew. While doing so, Sergeant River’s tank was hit, killing him and wounding the crew. Staff Sergeant Rivers’ fighting spirit and daring leadership were an inspiration to his unit and exemplify the highest traditions of military service.”

Second Lieutenant Charles L. Thomas, U.S. Army

Charles Leroy Thomas attended Cass Technical High School in Birmingham, Alabama, then went to study mechanical engineering at Wayne State University. During World War II, he was drafted into the Army and initially had enlistment orders in the infantry. Thomas went to officer training school and was commissioned as a second lieutenant with the 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion. In November 1944, Thomas’ tanks came across the Siegfried Line, a line of tank traps, or “dragon’s teeth,” on the border of France and Germany. After flanking a German position, his tank successfully pushed the enemy out.

On Dec.14, 1944, near the French village of Climbach, the tank destroyer battalion surged ahead of other infantry soldiers. While surrounded by hilly terrain, a German anti-tank gun had destroyed one of their tanks with a direct hit. While traveling in an M20 armored utility car across a field, the car exploded, sending glass into Thomas’ eyes and shrapnel into his body. He jumped out from the driver’s seat and got onto the roof to man the .50-caliber machine gun but was wounded again in the chest, arms, and legs. He hopped off and ordered his men to take cover. “I know I was sent out to locate and draw the enemy fire … but I didn’t mean to draw that much,” Thomas said in a later interview.

He survived the battle and forced the Germans again behind the Siegfried Line. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, which was upgraded to the MOH in 1997.

Private George Watson, U.S. Army

George Watson of Birmingham, Alabama, joined the U.S. Army in September 1942 and was sent to the Pacific Theater aboard the Dutch Steamer USAT Jacob. Watson wasn’t in combat arms nor were any of the members from the 29th Quartermaster Regiment ever prepared for the events that occurred on the morning of March 8, 1943. As they prepared to leave the ship and link up with their unit in the Porlock Harbor in New Guinea, a swarm of Japanese bombers appeared overhead. Moments later, bombs impacted and exploded, crippling their vessels.

The explosions threw men into the air and into the ocean. Several were badly hurt and unable to swim. They had seconds to live, and Watson knew it. He made several successful attempts to save lives by swimming back and forth to and from safety. He never stopped and was tragically dragged down by the violent suction from the sinking ship, costing him his life. Watson became the first African-American to be awarded the DSC, which was upgraded to the MOH in 1997.

KOREAN WAR

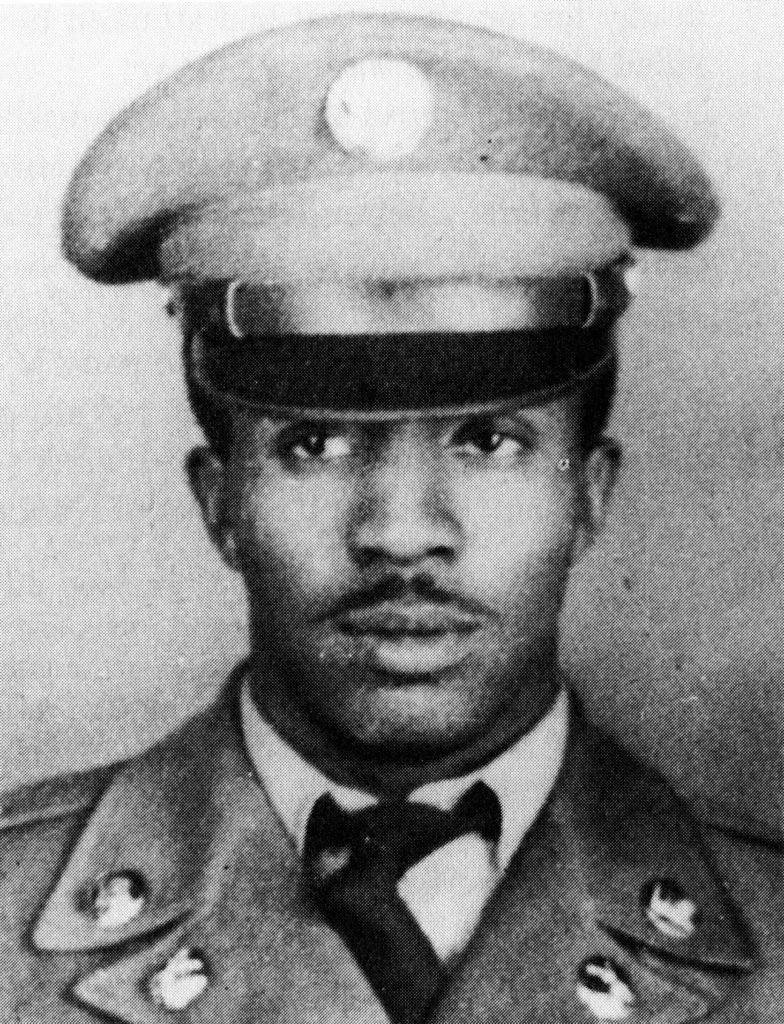

Sergeant Cornelius H. Charlton, U.S. Army

Cornelius H. Charlton joined the U.S. Army in 1946, one year after the end of World War II. He served stateside but saw combat during the Korean War. As a sergeant with the 24th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division, he led a desperate charge against a heavily fortified enemy position near the village of Chipo-ri on June 2, 1951. He was shot in the chest during the assault but continued up to the hilltop. He threw hand grenades, shot his rifle, and single-handedly overtook a mortar position despite being blasted by an enemy explosion. Charlton was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

Private First Class William Henry Thompson, U.S. Army

Private First Class William Henry Thompson was born in New York City on Aug. 16, 1927. He joined the U.S. Army’s 24th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division, serving as a machine gunner for his platoon. During the Battle of Musan, he sacrificed his life to save his fellow soldiers.

His citation reads: “While his platoon was reorganizing under cover of darkness, fanatical enemy forces in overwhelming strength launched a surprise attack on the unit. Pfc. Thompson set up his machine gun in the path of the onslaught and swept the enemy with withering fire, pinning them down momentarily thus permitting the remainder of his platoon to withdraw to a more tenable position. Although hit repeatedly by grenade fragments and small-arms fire, he resisted all efforts of his comrades to induce him to withdraw, steadfastly remained at his machine gun and continued to deliver deadly, accurate fire until mortally wounded by an enemy grenade. Pfc. Thompson’s dauntless courage and gallant self-sacrifice reflect the highest credit on himself and uphold the esteemed traditions of military service.”

VIETNAM WAR

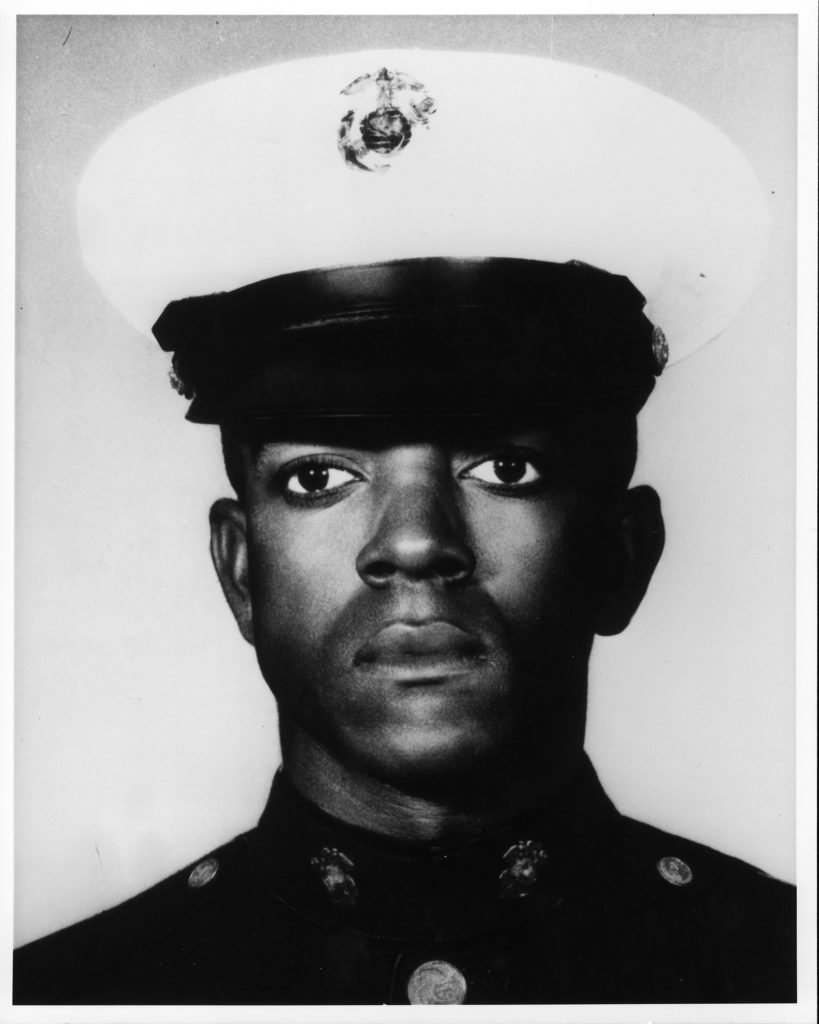

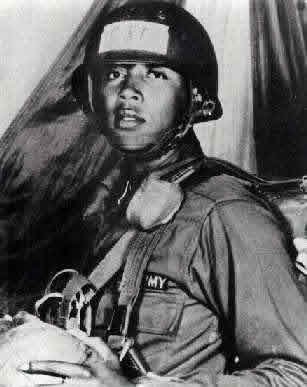

Private First Class James Anderson Jr., U.S. Marine Corps

Private First Class James Anderson Jr. became the first African-American Marine in history to receive the Medal of Honor. Anderson grew up in Los Angeles and attended junior college for a year before he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps in 1966. He served as a rifleman in the 2nd Platoon, Company F, 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marines, 3rd Marine Division. On Feb. 28, 1967, the 30-year-old Marine sacrificed his life to protect his fellow Marines. An enemy hand grenade landed at the feet of several Marines during an intense firefight. Anderson grabbed the grenade, pulled it to his chest, and braced for the explosion.

He became the first of five African-Americans in the history of the Marine Corps to receive the Medal of Honor.

Sergeant First Class Webster Anderson, U.S. Army

Sergeant First Class Webster Anderson served as Chief of Section in Battery A, 2d Battalion, 320th Artillery, 101st Airborne Infantry Division (Airmobile) near Tam Ky, Republic of Vietnam. A determined force of North Vietnamese Army soldiers launched an offensive on their defensive position with heavy mortar, rocket propelled grenade, recoilless rifle, and automatic weapon fire. Anderson mounted a completely exposed wall section of his howitzer and set up a defensive position of the battery. He directed devastating howitzer fire; between reloads, he fired his rifle and threw hand grenades.

As the firefight ensued, two enemy grenades exploded at his feet, knocking him down and severely injuring his lower extremities. He continued to provide effective fire against the enemy, despite not being able to stand. Grenades landed all around them, one coming within inches of one of his wounded teammates within the gun pit. Anderson grabbed it with his hand in an attempt to throw it away, but it exploded midair and wounded him again. Although he was fading in and out of consciousness, he refused medical evacuation and encouraged his men to fight to the end. Anderson was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions on Oct. 15, 1967.

Sergeant First Class Eugene Ashley Jr., U.S. Army

Eugene Ashley Jr. had combat experience from serving in the Korean War before he joined the 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne), 1st Special Forces, ODA-101. The North Vietnamese Army launched an assault between Feb. 6 and 7, 1968, against a U.S. Army Special Forces camp. Sappers carrying satchel charges, soldiers holding thermite grenades and flamethrowers, supported by a dozen PT-76 tanks, overran the Army Special Forces position. The carnage became known as the Battle of Lang Vei, and their rescue was coordinated by Ashley.

As a Senior Special Forces advisor, Ashley supported the Green Berets with high illumination mortar flares from afar. When communications with the camp ceased, he began calling in artillery and airstrikes. He gathered a small assault force of local partner forces and led five assaults against the enemy in an attempt to rescue the Green Berets. He braved a numerically superior force, dodged booby traps and satchel charges set in bunkers, and was seriously wounded by machine gun fire. He pressed on, and during his last attack, he called airstrikes directly on his own position to force the NVA to retreat. He lost consciousness due to lack of blood and his teammates carried him the rest of the way. However, an artillery round exploded near his position, and he was killed in action.

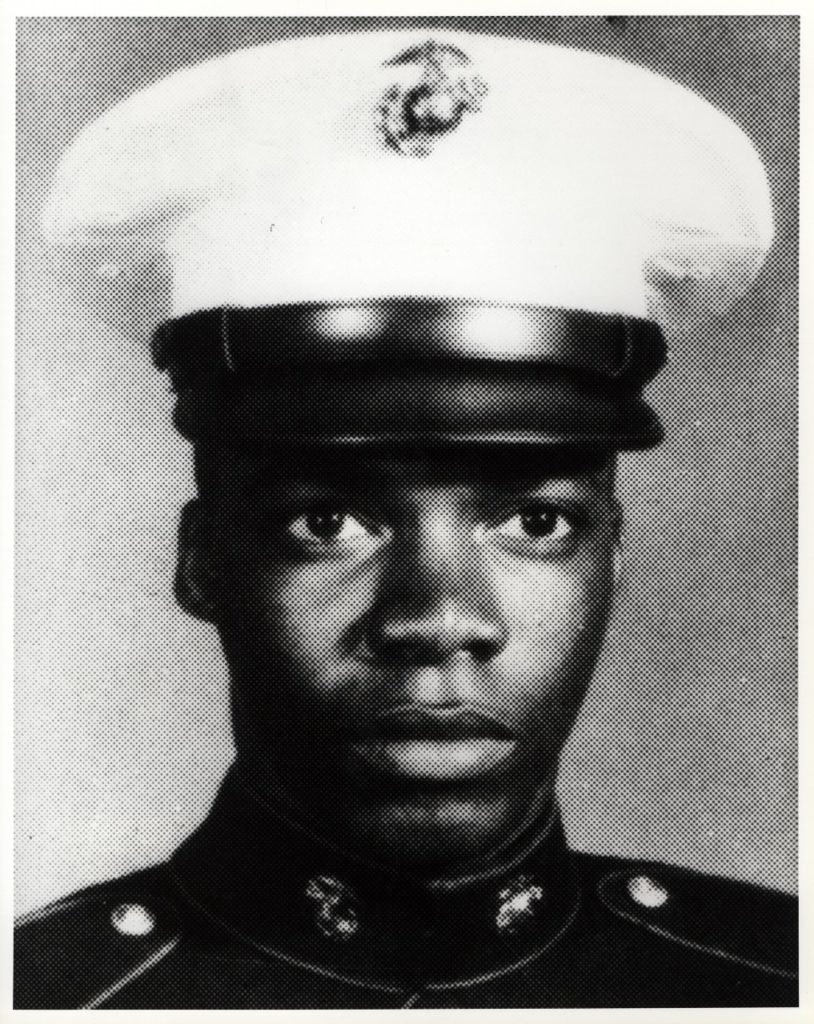

Private First Class Oscar P. Austin, U.S. Marine Corps

Oscar P. Austin served as an ammunitions man with Company E, 2nd Battalion, 7th Marine Division and deployed to Vietnam where he saved the life of a fellow Marine. At dawn on Feb. 23, 1969, the NVA launched a fierce raid against Austin’s base, using small-arms fire, hand grenades, and satchel charges. Seeing a fellow Marine slumped over in his foxhole, Austin sprinted across open ground to retrieve his wounded teammate. When he closed within distance of him, a hand grenade landed between them. Without hesitation, Austin dove and smothered the enemy hand grenade. The explosion left him severely wounded but conscious.

He awoke to see an NVA soldier standing over and pointing a rifle at the other wounded Marine. Austin threw himself between the rifle and the other Marine, sacrificing his life in the process. He was awarded the Medal of Honor, and the U.S. Navy immortalized his name when the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer was named the USS Oscar Austin (DDG-79).

Sergeant First Class William Maud Bryant, U.S. Army

William Maud Bryant was a senior NCO in the U.S. Army’s 5th Special Forces Group in Long Khánh Province, Vietnam. The 36-year-old inspired his teammates through a 34-hour battle while he moved through company positions and took intense direct fire from three NVA regiments. Bryant improved the defensive perimeter, unleashed accurate return fire with a devastating effect, and distributed ammunition. When the ammo ran dry, an emergency resupply was dropped from a hovering helicopter. Bryant ran into the open, retrieved the precious ammo, and continued to fight.

During a lull in the firefight, he led a patrol outside their perimeter to obtain intelligence on the enemy. The group was ambushed a second time with overwhelming automatic weapons fire and were pinned down. Bryant single-handedly repulsed an enemy attack with his small force. He identified a wounded enemy soldier near his patrol location and crawled forward alone under heavy fire to retrieve the soldier, capturing him to gather intelligence. The wounded soldier, however, had died, and Bryant crawled back to lead his men to their base. Despite being surrounded, Bryant led a second patrol to attempt to break through their encirclement. The patrol advanced some 200 meters but was pinned down by intense fire from fortified bunkers. Despite his wounds, Bryant rallied his men, called for helicopter gunship support, and directed heavy suppressive fire upon enemy positions. Following the last gunship attack, Bryant fearlessly charged an enemy automatic weapons position, overrunning it and destroying its three defenders. While he regrouped his small force, an enemy rocket mortally wounded him.

Gunnery Sergeant John Canley, U.S. Marine Corps

Retired Marine Sergeant Major John Canley arrived at the White House on Oct. 17, 2018, to receive the Medal of Honor from President Donald Trump. His previous award of the Navy Cross had been upgraded after careful consideration of his actions in Huế between Jan. 31, 1968 and Feb. 6, 1968. During the Tet Offensive, Canley served as a gunnery sergeant for Alpha 1/1 (1st Battalion, 1st Marines) as they pushed along Route 1 near the Perfume River. They were attacked by NVA forces as he led 150 Marines in a vicious urban assault fighting house to house. After his commanding officer was severely wounded — and despite being wounded himself — Canley took command and led his company into Hue City.

Once they reached the city, they were caught in a deadly crossfire. Canley set up and maneuvered a platoon to flank and eliminate several enemy positions. For the next three days, he led attacks against multiple fortified positions. On February 4, he led a group of Marines into an enemy-occupied building, cleared it room by room to eliminate enemy targets, and seized control of the building. He also used a large satchel charge to force the enemy to withdraw. On February 6, during a fierce firefight at a hospital compound, Canley twice scaled a wall in full view of the enemy to carry wounded Marines to safety.

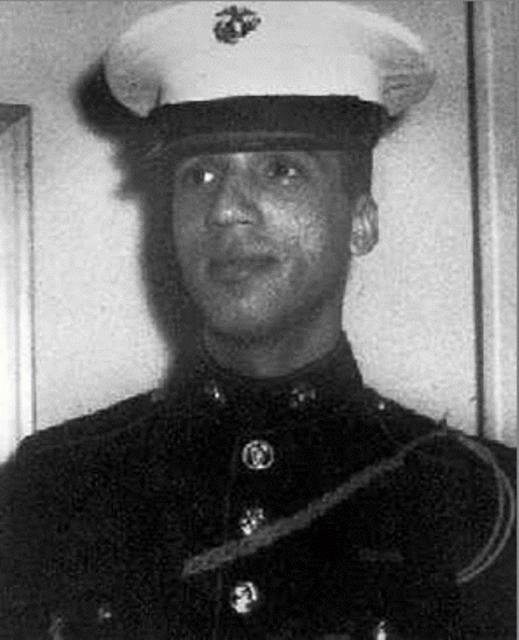

Sergeant Rodney M. Davis, U.S. Marine Corps

Sergeant Rodney Maxwell Davis served with the U.S. Marines during Operation SWIFT in a search-and-destroy mission in the Quang Nam Province on Sept. 6, 1967. Elements from another platoon in 1st Battalion, 5th Marines came under intense enemy fire from the NVA and were pinned down. Davis moved from man to man, encouraging them to fight on from their entrenched positions despite enemy hand grenades, small arms fire, and mortars. He threw hand grenades into enemy positions and silenced onrushing enemy attempting to overrun them. When an enemy hand grenade landed in his trench, Davis threw himself upon the grenade, absorbing the full blast with his body.

For these actions he was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. The frigate USS Rodney M. Davis (FFG-60) is named in his honor.

Private First Class Robert H. Jenkins Jr., U.S. Marine Corps

While serving with 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion, 3rd Marine Division, Private First Class Robert H. Jenkins Jr. sacrificed his life for his fellow Marine. The 20-year-old Florida native was serving as a machine gunner in the early morning of March 5, 1969, when his 12-man recon team was ambushed at Fire Support Base Argonne, just south of the Demilitarized Zone. The NVA fired mortars, automatic weapons, and threw several hand grenades. Jenkins and another Marine set up their machine gun position and returned fire. An NVA soldier threw a hand grenade into his emplacement, and Jenkins quickly pushed his teammate to the ground and hopped on top of his body to shield him. The blast seriously wounded Jenkins, and he ultimately died from his wounds.

Specialist Six Lawrence Joel, U.S. Army

Lawrence Joel served in 1st Battalion, 503rd Airborne Infantry, 173rd Airborne Brigade in the Iron Triangle located northwest of Saigon. He was a medic, and a well-concealed Viet Cong element launched an attack that wounded or killed nearly every soldier in their squad. As they proceeded to their objective, Joel provided immediate care to his teammates but received a painful machine gun wound to his leg. He administered morphine to numb the pain, bandaged it up, and exposed himself to hostile fire while searching for more of his wounded teammates.

Joel was struck a second time in his thigh, but he dragged himself across the battlefield to treat 13 more men before he ran out of medical supplies. Despite his lack of gear to utilize, Joel saved the life of another soldier by placing a plastic bag over a severe chest wound to congeal the blood. He obtained more medical supplies from a responding platoon and continued to provide life-saving aid. His citation reads, “After the 24-hour battle subsided and the Viet Cong dead numbered 410, snipers continued to harass the company. Throughout the long battle, SP6 Joel never lost sight of his mission as a medical aidman and continued to comfort and treat the wounded until his own evacuation was ordered. His meticulous attention to duty saved a large number of lives and his unselfish, daring example under most adverse conditions was an inspiration to all.”

He became the first living African-American Medal of Honor recipient since the Spanish-American War.

Specialist Five Dwight H. Johnson, U.S. Army

Dwight H. (Skip) Johnson’s life was tragic. After surviving the Vietnam War, he was shot and killed by a store clerk when he attempted an armed robbery. At only 23 years old, he was a hero of Vietnam and a villain of his hometown, Detroit.

As a tank driver during the war, Johnson’s platoon of four M-48 tanks were traveling down a road along the Ho Chi Minh Trail when they were ambushed by overwhelming firepower. His tank’s track fell off and couldn’t advance. He climbed out of the tank armed only with a .45 pistol. He killed several NVA soldiers before running out of ammunition. He picked up a submachine gun, dodged anti-tank fire, and charged forward, killing enemy soldiers on his way to save his friends inside the burning tank. The firefight was so intense that he defeated an enemy soldier in hand-to-hand combat with the stock of his submachine gun.

His citation reads, “Now weaponless, Specialist Johnson ignored the enemy fire around him, climbed into his platoon sergeant’s tank, extricated a wounded crewmember and carried him to an armored personnel carrier. He then returned to the same tank and assisted in firing the main gun until it jammed. In a magnificent display of courage, Specialist Johnson exited the tank and again armed only with a .45 caliber pistol, he engaged several North Vietnamese troops in close proximity to the vehicle. Fighting his way through devastating fire and remounting his own immobilized tank, he remained fully exposed to the enemy as he bravely and skillfully engaged them with the tank’s externally-mounted .50 caliber machine gun; where he remained until the situation was brought under control.”

Private First Class Ralph H. Johnson, U.S. Marine Corps

Ralph H. Johnson was a native of Charleston, South Carolina, who participated in a four-day operation called Operation Rock as a reconnaissance scout with Company A, 1st Reconnaissance Battalion, 1st Marine Division. Johnson and his 15-man recon patrol were at an observation post on Hill 146 overlooking the Quan Duc Valley located deep in enemy-controlled territory. On March 5, 1968, a platoon-size hostile force engaged their squad with automatic weapons, satchel charges, and hand grenades. One of the hand grenades landed between Johnson and two other Marines. Johnson jumped onto the explosive device and was killed instantly when it exploded.

On March 24, 2018, a brand-new Arleigh Burke-class guided missile destroyer was commissioned in his honor.

Private First Class Garfield M. Langhorn, U.S. Army

Private First Class Garfield M. Langhorn was a man of faith who planned to marry his fiancee when he returned from Vietnam. On Jan. 15, 1969, he sacrificed his life when he hurled his body on top of a hand grenade to save others around him. As a radio operator serving with Troop C near Plei Djereng in the Pleiku jungle, his platoon was inserted into a landing zone to rescue two pilots from a shot-down Cobra helicopter. He controlled the air assets as his team hacked through the thick jungle vegetation to reach the aircraft, but before they could load the bodies onto the helicopter, camouflaged bunkers with NVA soldiers inside opened up on them on their right flank.

His citation continues, “Pfc. Langhorn immediately radioed for help from the orbiting gunships, which began to place minigun and rocket fire on the aggressors. He then lay between the platoon leader and another man, operating the radio and providing covering fire for the wounded who had been moved to the center of the small perimeter. Darkness soon fell, making it impossible for the gunships to give accurate support, and the aggressors began to probe the perimeter. An enemy hand grenade landed in front of Pfc. Langhorn and a few feet from personnel who had become casualties. Choosing to protect these wounded, he unhesitatingly threw himself on the grenade, scooped it beneath his body and absorbed the blast. By sacrificing himself, he saved the lives of his comrades.” He was 20 years old.

Sergeant First Class Matthew (Bill) Leonard, U.S. Army

Matthew (Bill) Leonard was a veteran of the Korean War and the Vietnam War. During a stint in Germany, his wife and five kids enjoyed cooking and serving Southern barbecue, an Alabama staple, to their new foreign friends. He was nearing retirement when the U.S. got involved in Vietnam, and he was sent to combat with the 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division. His wife remembered the phone call when her husband told her, “I had to do it. They need experienced soldiers over there.”

On Feb. 28, 1967, several younger soldiers were wounded by a large Viet Cong force. Leonard organized a defensive perimeter during a lull in the fight, but noticed a teammate lying on the ground. Leonard stood up and dragged the man to cover but was struck by a sniper, the bullet shattering his left hand. He refused medical attention, moved into position to direct fire against a well-camouflaged enemy position, and focused his attention on a machine gun team that was firing at their entire squad.

“Leonard quickly crawled to the gun position and was helping to clear the malfunction when the gunner and other men in the vicinity were wounded by fire from the enemy machine gun,” reads his award citation. “P/Sgt. Leonard rose to his feet, charged the enemy gun and destroyed the hostile crew despite being hit several times by enemy fire. He moved to a tree, propped himself against it, and continued to engage the enemy until he succumbed to his many wounds. His fighting spirit, heroic leadership, and valiant acts inspired the remaining members of his platoon to hold back the enemy until assistance arrived.”

Sergeant Donald Russell Long, U.S. Army

Sergeant Donald Russell Long was a Ohio native of mixed race (black, white, American Indian) who served in the U.S. Army’s 4th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division. While conducting a reconnaissance patrol with Troop B and C, their teams were attacked by a Viet Cong regiment that employed mortars, recoilless rifles, and machine guns. The enemy attackers concealed themselves along the road. Long left the safety of his armored personnel carrier to carry the wounded to medevac helicopters nearby. As the enemy attempted to overrun them, Long inspired his teammates while completely exposed to enemy fire and fired rifle grenades toward their positions.

His citation continues, “When the enemy threatened to overrun a disabled carrier nearby, Sgt. Long again disregarded his own safety to help the severely wounded crew to safety. As he was handing arms to the less seriously wounded and reorganizing them to press the attack, an enemy grenade was hurled onto the carrier deck. Immediately recognizing the imminent danger, he instinctively shouted a warning to the crew and pushed to safety one man who had not heard his warning over the roar of battle. Realizing that these actions would not fully protect the exposed crewmen from the deadly explosion, he threw himself over the grenade to absorb the blast and thereby saved the lives of 8 of his comrades at the expense of his life.”

Sergeant First Class Melvin Morris, U.S. Army

On March 18, 2014, Sergeant First Class Melvin Morris’ Distinguished Service Cross award was reviewed alongside 6,500 cases previously overlooked for racial bias or ethnic prejudices. He was one of 24 men to be upgraded to the Medal of Honor. He volunteered for service three times — once for Airborne; again for the Green Berets, where he served with 5th Special Forces Group; and a third time for Vietnam.

On Sept. 17, 1969, there was no activity in the vicinity of Chi Lang village, and that got Morris’ attention. And then came the ambush. In rapid succession, Morris’ team sergeant was killed, his team captain and radio operator was seriously wounded, and his intelligence sergeant stepped on a land mine. Morris reorganized his assault force and advanced forward to recover their bodies. Morris’ three-man element was twice wounded by enemy fire, but Morris escaped unscathed.

“Staff Sergeant Morris charged forward into withering enemy fire with only his men’s suppressive fire as cover,” his citation continues. “While enemy machine gun emplacements continuously directed strafing fusillades against him, Staff Sergeant Morris destroyed the positions with hand grenades and continued his assault, ultimately eliminating four bunkers. Upon reaching the bunker nearest the fallen team commander, Staff Sergeant Morris repulsed the enemy, retrieved his comrade and began the arduous trek back to friendly lines. He was wounded three times as he struggled forward, but ultimately succeeded in returning his fallen comrade to a friendly position.”

Private First Class Milton L. Olive III, U.S. Army

Chicago-native Milton L. Olive III joined the U.S. Army’s 503rd Infantry Regiment, 173rd Airborne Brigade and served at Phu Cuong, Vietnam. During a patrol through the jungle to locate Viet Cong, his platoon was ambushed by a heavy volume of enemy gunfire and got pinned down. They retaliated by assaulting Viet Cong positions, which caused them to flee. Olive and four other soldiers pursued the Viet Cong through the jungle when an enemy hand grenade landed between them. Without thinking of saving his own life, Olive grabbed the grenade with his hand and fell to the ground, absorbing the blast with his body.

Captain Riley L. Pitts, U.S. Army

Captain Riley L. Pitts was from Wichita, Kansas, and left behind a wife and two kids. He served as a captain in the 27th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Regiment as they deployed to Ap Dong, Vietnam. The 30-year-old was killed in action on Oct. 31, 1967, fighting a fierce battle as his kids were gearing up to celebrate Halloween. Immediately after landing in Ap Dong, Pitts’ company took incoming fire, and he led a counterassault overrunning several enemy positions. However, it was a desperate fight for control as they were pushed back and advanced forward repeatedly.

Enemy fire from four bunkers, two of which were within 15 meters of Pitts, prevented him from maneuvering his company. The dense jungle foliage made his rifle ineffective, so he grabbed a nearby M-79 grenade launcher. Pitts also used Chinese Communist grenades captured from a Viet Cong and lobbed it into a bunker in front of him. The grenade, however, bounced back to his position; he jumped on it and waited for the explosion. It never came, and he recovered himself to call for artillery fire. He killed one enemy soldier and continued to push into the enemy positions until he was mortally wounded.

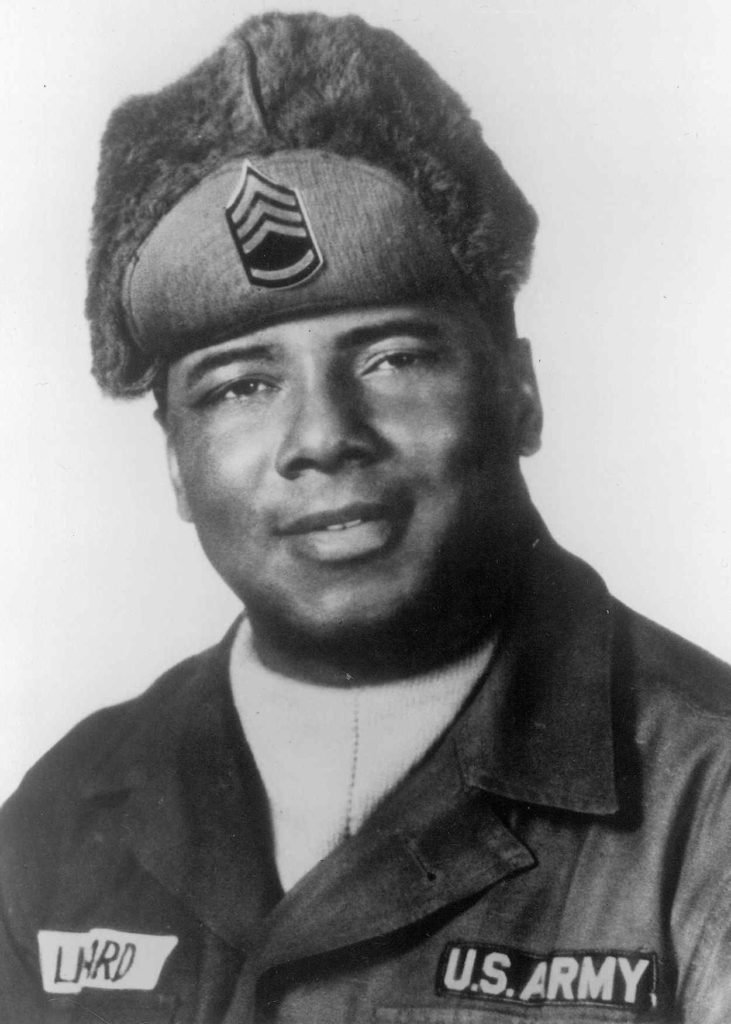

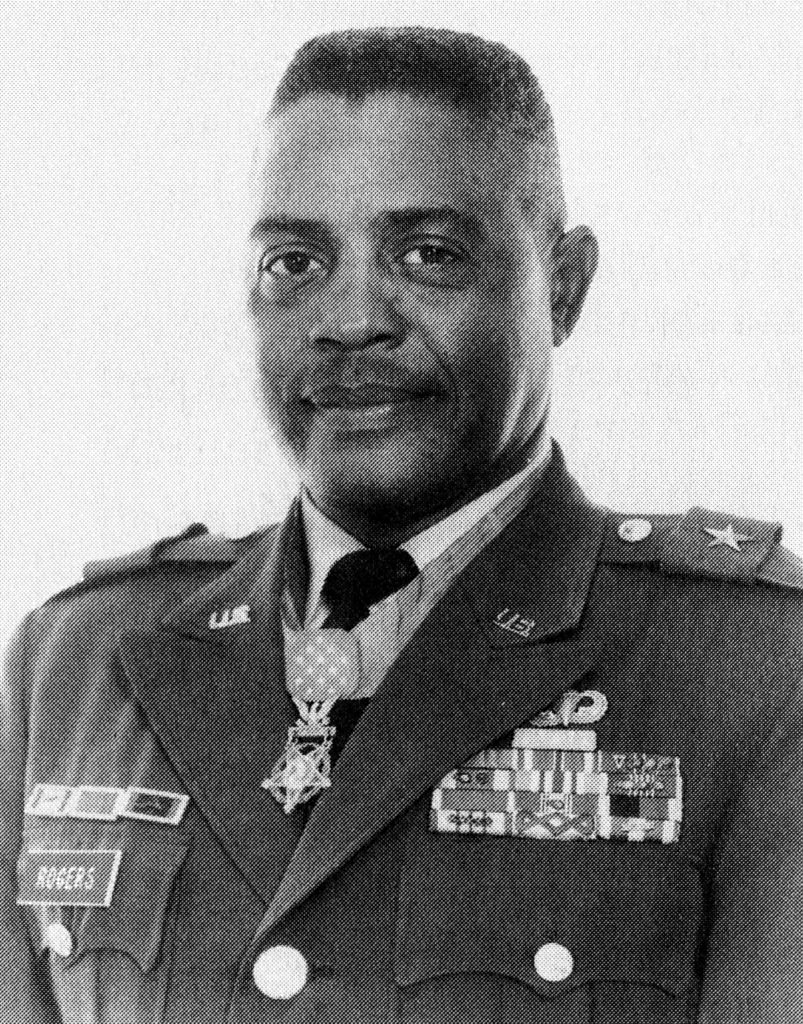

Major General Charles Calvin Rogers, U.S. Army

In 1980, Major General Charles Calvin Rogers became the highest ranking black Medal of Honor recipient. On Nov. 1, 1968, serving with the 5th Field Artillery Regiment, 1st Infantry Regiment near the Cambodian border, Rogers distinguished himself in the early morning hours despite being severely wounded. The enemy launched a coordinated bombardment of heavy mortar, rocket, and rocket-propelled-grenade (RPG) fire on their first support base. In addition, an enemy ground element, including sappers, peppered the defensive barriers with bangalore torpedos.

Rogers rallied his artillery crewman and placed effective howitzer fire on enemy positions despite being knocked to the ground and wounded by an exploding enemy round. As he led an element and overtook a captured friendly position, he was wounded a second time. He pressed on and killed several enemies. A second wave was countered by a second counterattack that he personally led.

“At dawn the determined enemy launched a third assault against the fire base in an attempt to overrun the position,” his citation reads. “Lieutenant Colonel Rogers moved to the threatened area and directed lethal fire on the enemy forces. Seeing a howitzer inoperative due to casualties, Lieutenant Colonel Rogers joined the surviving members of the crew to return the howitzer to action. While directing the position defense, Lieutenant Colonel Rogers was seriously wounded by fragments from a heavy mortar round which exploded on the parapet of the gun position. Although too severely wounded to physically lead the defenders, Lieutenant Colonel Rogers continued to give encouragement and direction to his men in the defeating and repelling of the enemy attack.”

First Lieutenant Ruppert L. Sargent, U.S. Army

First Lieutenant Ruppert Sargent became the first black officer in history to posthumously receive the Medal of Honor for his actions on March 15, 1967, at Hậu Nghĩa Province, Vietnam.

His citation reads: “While leading a platoon of Company B, First Lieutenant Sargent was investigating a reported Viet Cong meeting house and weapons cache. A tunnel entrance which First Lieutenant Sargent observed was booby trapped. He tried to destroy the booby trap and blow the cover from the tunnel using hand grenades, but this attempt was not successful. He and his demolition man moved in to destroy the booby trap and cover which flushed a Viet Cong soldier from the tunnel, who was immediately killed by the nearby platoon sergeant. First Lieutenant Sargent, the platoon sergeant, and a forward observer moved toward the tunnel entrance. As they approached, another Viet Cong emerged and threw two hand grenades that landed in the midst of the group. First Lieutenant Sargent fired three shots at the enemy then turned and unhesitatingly threw himself over the two grenades. He was mortally wounded, and his two companions were lightly wounded when the grenades exploded.”

Private First Class Clarence Sasser, U.S. Army

Private First Class Clarence Sasser deployed to Ding Tuong Province, Vietnam, and received the Medal of Honor for his actions on Jan. 10, 1968. The 22-year-old from Houston, Texas, worked as a medical aidman with 3rd Battalion, 60th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Regiment. While on a reconnaissance mission during an air assault, his team was overwhelmed by heavy small arms, recoilless rifles, machine guns, and rocket fire from fortified enemy positions on three sides of the Landing Zone. In only a matter of minutes, 30 casualties needed emergency medical attention.

“Without hesitation, Specialist Fifth Class Sasser ran across an open rice paddy through a hail of fire to assist the wounded,” his citation reads. “After helping one man to safety, he was painfully wounded in the left shoulder by fragments of an exploding rocket. Refusing medical attention, he ran through a barrage of rocket and automatic weapons fire to aid casualties of the initial attack and, after giving them urgently needed treatment, continued to search for other wounded. Despite two additional wounds immobilizing his legs, he dragged himself through the mud toward another soldier 100 meters away. Although in agonizing pain and faint from loss of blood, Specialist Fifth Class Sasser reached the man, treated him, and proceeded on to encourage another group of soldiers to crawl 200 meters to relative safety. There he attended their wounds for five hours until they were evacuated.”

Staff Sergeant Clifford Chester Sims, U.S. Army

Staff Sergeant Clifford Chester Sims served as a squad leader with 2nd Battalion, 101st Airborne Division while fighting aggressor forces in the city of Hue, Vietnam. On Feb. 21, 1968, Company D encountered a heavily fortified position concealed within a dense wooded area. Sims led his squad in a furious assault to relieve 1st Platoon, which was desperately fighting to avoid being overrun. He regained the initiative and covered his men to advance and link up with 3rd Platoon. He moved with 30 meters of a brick enemy position, but nearby ammunition was set on fire. They moved to a safer position, but two members of his squad were injured by the subsequent ammo explosion.

“While continuing through the dense woods amidst heavy enemy fire, Staff Sergeant Sims and his squad were approaching a bunker when they heard the unmistakable noise of a concealed booby trap being triggered immediately to their front,” his citation continues. “Staff Sergeant Sims warned his comrades of the danger and unhesitatingly hurled himself upon the device as it exploded, taking the full impact of the blast. In so protecting his fellow soldiers, he willingly sacrificed his life.”

First Lieutenant John E. Warren Jr., U.S. Army

First Lieutenant John E. Warren Jr. served as a platoon leader for Company C (Mechanized), 2d Battalion, 22d Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division in the Tay Ninh Province, Republic of Vietnam.

“While moving through a rubber plantation to reinforce another friendly unit, Company C came under intense fire from a well-fortified enemy force,” his citation reads. “Disregarding his safety, First Lieutenant Warren with several of his men began maneuvering through the hail of enemy fire toward the hostile positions. When he had come to within six feet of one of the enemy bunkers and was preparing to toss a hand grenade into it, an enemy grenade was suddenly thrown into the middle of his small group. Thinking only of his men, First Lieutenant Warren fell in the direction of the grenade, thus shielding those around him from the blast. His action, performed at the cost of his life, saved three men from serious or mortal injury.”

PEACETIME

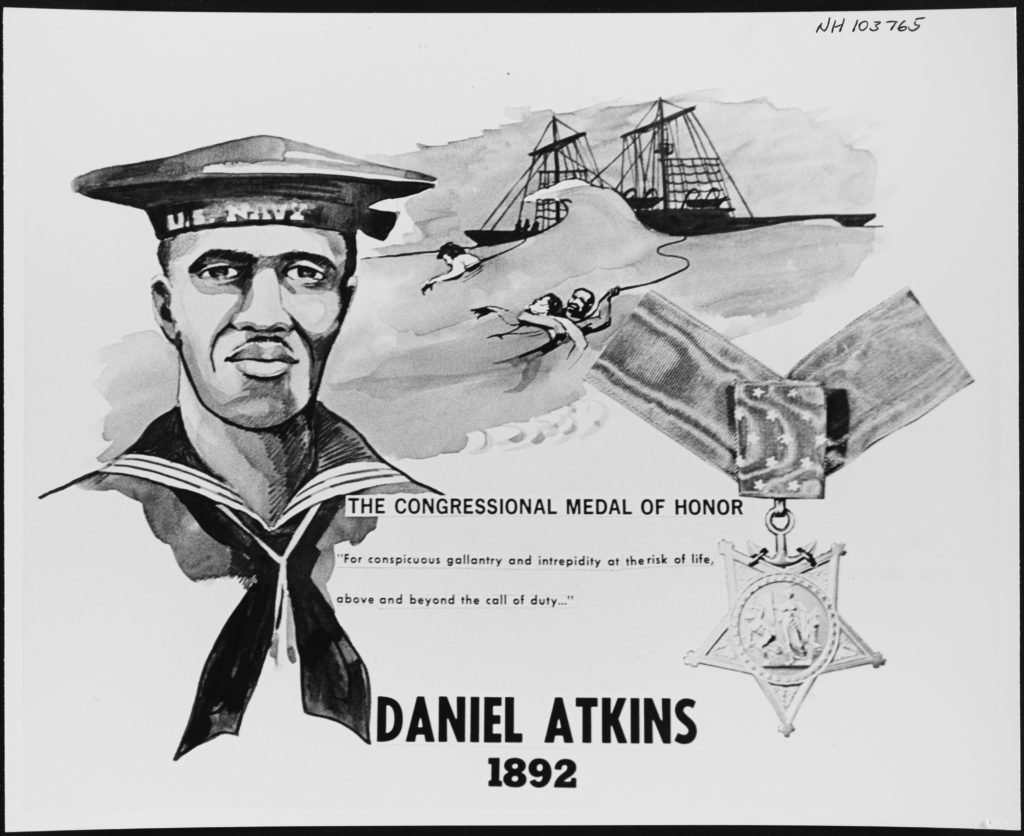

Ship’s Cook First Class Daniel Atkins, U.S. Navy

Before World War II, the Medal of Honor was awarded to sailors for rescuing or attempting to rescue someone from drowning. Daniel Atkins and the seven remaining members on this list received that distinction. A native of Brunswick, Virginia, Atkins served aboard the USS Cushing as a Ship’s Cook First Class. He “attempted to save the life of the late Ensign Joseph C. Breckenridge, U.S. Navy, who fell overboard at sea from that vessel” on May 20, 1898. For these actions he received the Medal of Honor.

Ordinary Seaman John Davis, U.S. Navy

Ordinary Seaman John Davis served in the U.S. Navy and received the Medal of Honor for rescuing another sailor who could not swim as he fell overboard. His citation reads: “On board the U.S.S. Trenton, Toulon, France, February 1881. Jumping overboard, Davis rescued Augustus Ohlensen, coxswain, from drowning.”

Alphonse Girandy, U.S. Navy

Alphonse Girandy served during the Spanish-American War, but his citation is for life-saving measures rather than combat valor. “Serving on board the U.S.S. Petrel, for heroism and gallantry, fearlessly exposing his own life to danger for the saving of others, on the occasion of the fire on board that vessel, March 31, 1901,” his citation reads.

Seaman John Johnson, U.S. Navy

There is not much known about Medal of Honor recipient John Johnson. Records show that he was a seaman on the steamship USS Kansas when an accident occurred off the coast of Nicaragua. “Johnson displayed great coolness and self-possession at the time Comdr. A. F. Crosman and others were drowned and, by extraordinary heroism and personal exertion, prevented greater loss of life,” his citation reads. He was awarded the MOH on July 9, 1872.

William Johnson, U.S. Navy

William Johnson was a St. Vincent West Indies native and served aboard the USS Adams in the Navy Yard off Mare Island, California. On Nov. 14, 1879, Johnson witnessed Daniel W. Kloppen, a workman, fall overboard. As panic and aggressive splashing ensued, Johnson hurled himself into the ocean and rescued him from drowning. For his life-saving actions, he was awarded the Medal of Honor.

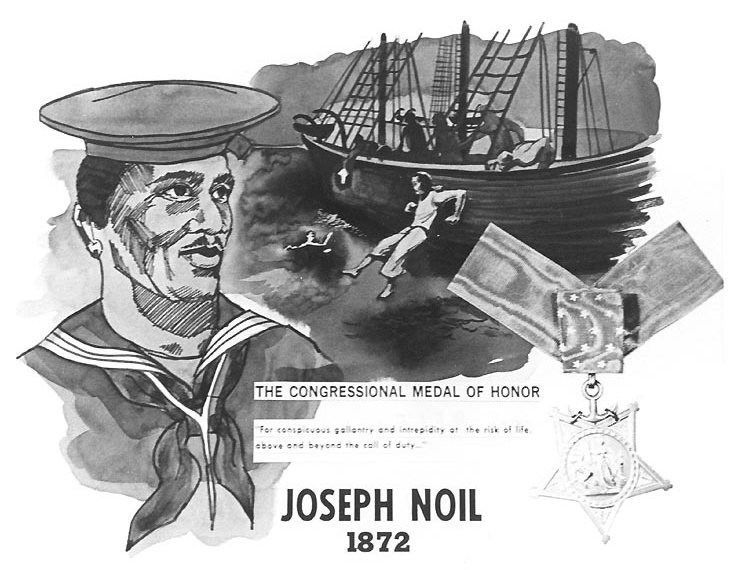

Seaman Joseph B. Noil, U.S. Navy

Seaman Joseph B. Noil served aboard the USS Powhatan, and on Dec. 26, 1867, the call for man overboard echoed across the boat. Boatswain Jack Walton had fallen into the frigid water and had moments before he would become a relic of the deep. Noil threw a rope out to Walton, and Walton latched onto it. Despite going under several times in the waves, Noil heaved him up and onto the ship’s deck. Captain Peirce Crosby, his commanding officer later wrote. “Mr. Walton, when brought on board, was almost insensible, and would have perished but for the noble conduct of Noil.”

As a result of a misspelling on his 1882 death certificate, Noil was buried under a different name. In 2017, his headstone was restored with not only his correct name but also his distinction as a Medal of Honor recipient.

Seaman John Smith, U.S. Navy

John Smith is a common name — so common, in fact, that three other John Smiths have been awarded the Medal of Honor. However, the only African-American John Smith to be awarded the MOH did so for a selfless life-saving act. Born in 1854, the Bermuda native served as a seaman aboard the USS Shenandoah off the coast of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. On Sept. 19, 1880, fellow shipmate Fireman James Grady fell overboard and started to drown. Smith disregarded any danger to his own person by jumping into the ocean and rescuing Grady.

Robert Augustus Sweeney, U.S. Navy

Only 19 servicemen in the history of the U.S. military have the distinction of two Medal of Honor awards — and Robert Augustus Sweeney is the only black multiple MOH recipient. He is also the only recipient to earn two awards during peacetime. Sweeney was honored for two seperate life-saving actions. The first came in 1881 when he attempted to rescue a shipmate who fell overboard the USS Kearsarge. He held onto the fallen shipmate for half an hour before help arrived. His second award came for similar efforts in the New York Navy Yard. There was a gangplank between the USS Yantic and the USS Jamestown, and sailors had to watch their step in order to cross. A.A. George, a cabin boy, was crossing when he missed a step and fell into the water. Sweeney, along with a USS Jamestown sailor named J.W. Norris, leapt after the boy and saved him.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.