How 1985’s ‘Bloods: Black Veterans in Vietnam, An Oral History’ Relates to Our Current Wars

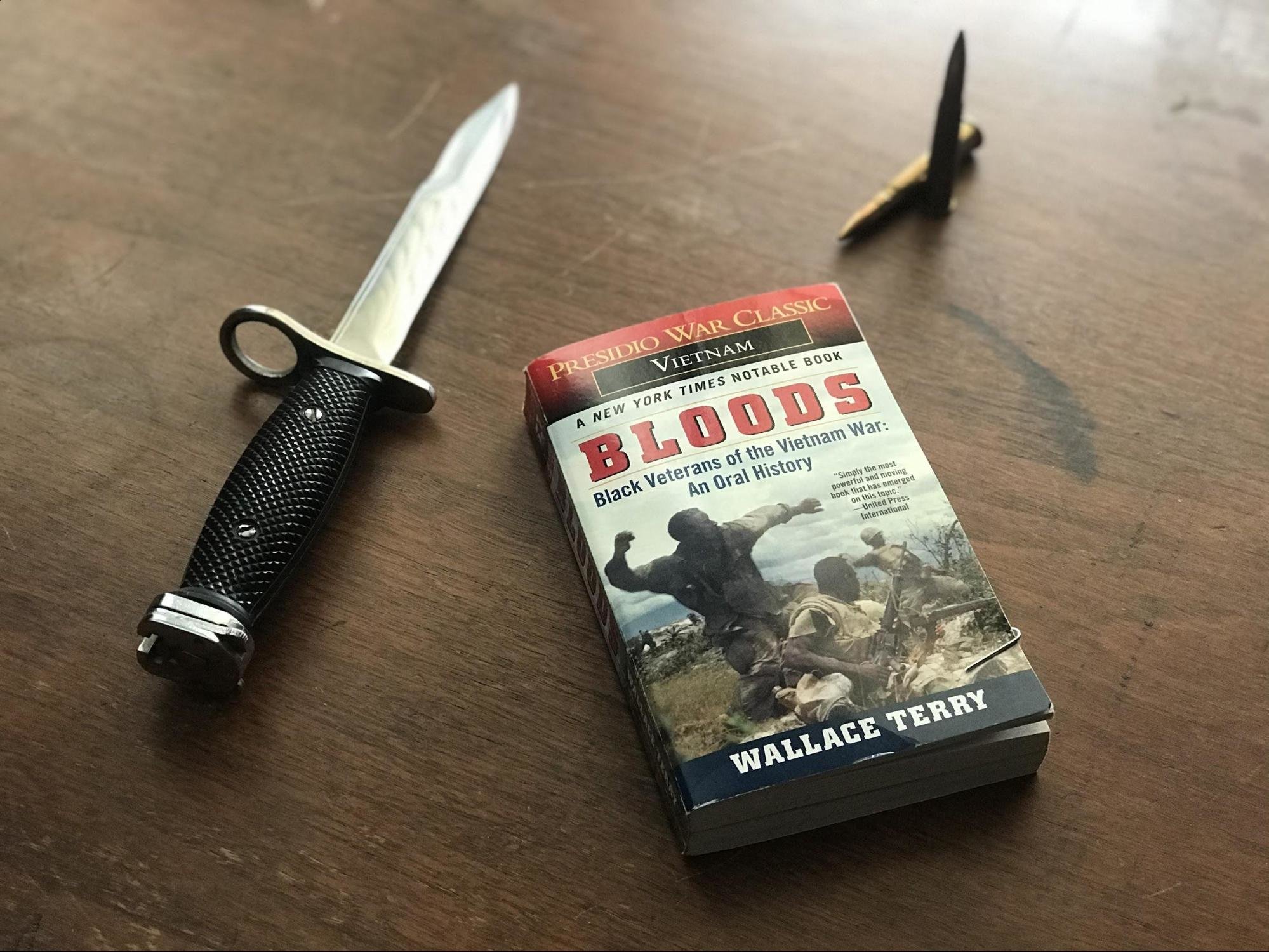

Photo by Mac Caltrider/Coffee or Die Magazine.

During the nearly 19 years America was involved in Vietnam, uncertainty abounded. Communism was spreading rapidly around the globe, America fought to end institutionalized racism, and a minor military operation in Southeast Asia devolved into the nation’s longest war. And while all Americans faced this shared uncertainty, no single demographic shouldered more of the burden than African American service members and veterans. Tasked with winning a conflict no longer supported by the public, Black troops had to navigate the murky waters of life at war with the additional hurdle of racial discrimination — a hardship not shared by their white brothers-in-arms.

Bloods: Black Veterans in Vietnam, An Oral History by Wallace Terry is the definitive oral history of the African American soldier’s experience during the Vietnam War. The New York Times Notable Book serves no agenda and provides no additional commentary on each of the 20 interviews, rigidly adhering to the veterans’ own words.

In the introduction, Terry describes his multiple assignments to Vietnam, and how, over time, the outlook toward war shifted among African American troops. He describes how in 1967 nearly all Americans in Vietnam, white and Black, felt strongly that the war was necessary to stop communism and preserve democracy. Most troops also believed the war to be easily winnable. In the early years of the war, relations between white and Black troops were positive; however, as the war dragged on and “the professionals” were replaced with draftees, race relations and the outlook on the war both deteriorated.

Following the brief introduction, Bloods dives directly into the soldiers’ experiences. Terry finds a fair balance between military branches, occupations, and ranks. From enlisted Army soldiers to naval officers, from Marine NCOs to Air Force pilots, Bloods covers the entire spectrum of Black service in Vietnam, revealing a common theme of frustration. This sentiment shines through in many forms but first in reference to the elusive enemy. Many of the veterans shared their resentment for fighting an enemy that used innocent civilians as weapons. Similar to the enemies America would face in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Viet Cong often hid among civilians, using them as shields.

Archie Biggers, a Marine platoon commander, describes the instance that began his hatred for such tactics:

“There was this kid, maybe two or three years old. He hadn’t learned to walk too well yet, but he was running down the street. And a Marine walked over to talk to the kid, touched him, and they both blew up. They didn’t move. It was not as if they stepped on something. The kid had to have the explosive around him. It was a known tactic that they wrapped stuff around kids. That Marine was part of the security force around Dong Ha, a lance corporal. He was trying to be friendly. I think it stinks. If those guys were low enough to use kids to bait Americans or anybody to this kind of violent end, well, I think they should be eliminated.”

Lt. Biggers’ anger only grew as his time in Vietnam dragged on. The rules of engagement he was charged with enforcing continuously changed. His Marines were restricted to fight on one side of the DMZ; they were prohibited from firing unless fired upon first and denied the ability to pursue the enemy if they fled. He aired his grievances with the “people in Washington who don’t really know what we’re dealing with” and joked about being required by law to smile first before shooting.

Biggers faced even more confusing emotions after returning home. While on recruiting duty in the nation’s capital, Biggers visited Howard University, a historically Black university. Expecting a hero’s welcome, he was instead ridiculed for being “Uncle Sam’s flunky.” Despite his having attended a historically Black university himself, the students he held so much in common with criticized his service and ridiculed the Purple Heart pinned to his chest. Biggers’ experience of being shunned by both white Americans who opposed the war and by African Americans for having served a “white agenda” was an experience shared by many returning veterans.

High casualty rates among Black troops exacerbated already dwindling support for the war. In the early years of the war, African Americans made up 23% of all fatalities. The resulting outrage caused the United States to set in place regulations ending discriminatory duty assignments. By the end of the war this rate dropped to 14%, still an unequal reflection of the population. Black veterans struggled with the duality of upholding what they viewed as patriotic duty and dealing with unfair treatment.

Lt. Cmdr. William Norman, a combat warfare officer in the US Navy, ultimately left the military due to inequalities he witnessed. Despite taking immense satisfaction from doing his job well and possessing a genuine love for serving, Norman explains:

“I was not frustrated with the war as much as I was frustrated with the role of blacks in the Navy in that war. The Navy was asking black people to take part in a war while subjecting them to institutional racism — institutional racism intentionally. You could go aboard a carrier with 5,000 people, and you would find the overwhelming majority of the blacks in the lowest level jobs, in the dirtiest jobs, down in the laundry room, down in the bowels of the ship. You walk into the areas where I work, with all the sophisticated computers, and it would look as if there were no blacks on the entire ship.”

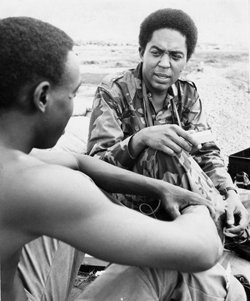

Norman’s revealing interview about the discrimination he faced in the Navy is quickly juxtaposed by a conversation with West Point graduate Capt. Joseph Anderson. Anderson served as a company commander in the 1st Cavalry Division and found the military to be the “most integrated institution in American society.” He viewed the Army as a place for him to rise above the racial discrimination still prominent in civilian spheres. With few equal opportunities for African Americans in private industries, Anderson explained how “as a graduate of West Point, I was an officer and a gentleman by act of Congress. Where else could a black go and get a label just like that?”

Anderson took the opportunity seriously. Labeling himself “gung-ho,“ Anderson went on to earn the Silver Star for finding and rescuing the survivors of “the lost platoon” near LZ Pink. Much of his time in Vietnam was captured on film in the 1967 documentary The Anderson Platoon. After returning from Vietnam, Anderson went on to teach at West Point and serve 13 years with the 82nd Airborne Division.

Bloods includes less-volatile experiences of those serving in noncombat capacities but does not shy away from more disturbing scenes endured by those on the front lines.

Arthur Woodley Jr., aka Cyclops, was a Green Beret with the 5th Special Forces Group and shares some of the darkest stories in the book. Woodley noticed in basic training that white and Black soldiers tended to segregate themselves: “It seemed like the dark-skinned brothers got most of the dirty details, while light-skinned brothers and Europeans got the easy chores.”

In an attempt to escape this, Woodley worked toward becoming a member of Special Forces, where race was not a factor in duty assignment. He later volunteered to be a part of a Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol (LRRP) and worked alongside an outspoken KKK member. While operating near An Khe to recover a downed helicopter crew, Woodley’s patrol came across one of the pilots.

“We came across this fella, a white guy, who was staked to the ground. […] And he had been peeled from his upper part of chest to down to his waist. Skinned. Like they slit your skin with a knife. And they take a pair of pliers and they just peel the skin off your body and expose it to the elements. […] We was even afraid to unstake him from the stakes, because the maggots and flies were eating at the exposed flesh so much. The man had maggots in his armpits and maggots in his throat and maggots in his stomach. […] You could see the flesh holes that the animals — wild dogs, rats, field mice, anything — had eaten through his body. With the blood loss that he had, it was a miracle that the man was still alive.”

The wounded man begged to be killed, and with only six men on the patrol and no litter, Woodley eventually obliged and shot him. After returning from the mission, he was told there would be an investigation and he was threatened with court-martial, but nothing ever came of it. Woodley continues about his time as a LRRP and describes some of the harsh realities of fighting an unwinnable war. His chapter stands above the rest, not for his unbelievable depictions of jungle fighting but more for his descriptions of coming home. The impact his moral injuries had on his ability to successfully integrate back into society is described with a level of candor seldom found in war stories. Woodley neatly simplifies the country’s eventual withdrawal from Vietnam: “The government kept handicapping us one way or ’nother. I don’t think America lost. I think they gave up.”

Similarities with the recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have caused a renewed effort to understand Vietnam and what exactly went wrong. With this renewed focus comes the need to reflect on the role African American soldiers played and the unique challenges they faced while fighting for a country that continued to deny them equality. Wallace Terry’s Bloods captures this important piece of American history in a way no one else has. While scholars attempt to understand the war and those who fought it, nothing can replace the invaluable resource of these oral histories.

Bloods: Black Veterans in Vietnam, An Oral History by Wallace Terry, Presidio Press, 320 pages, $9

Mac Caltrider is a senior staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. He served in the US Marine Corps and is a former police officer. Caltrider earned his bachelor’s degree in history and now reads anything he can get his hands on. He is also the creator of Pipes & Pages, a site intended to increase readership among enlisted troops. Caltrider spends most of his time reading, writing, and waging a one-man war against premature hair loss.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.