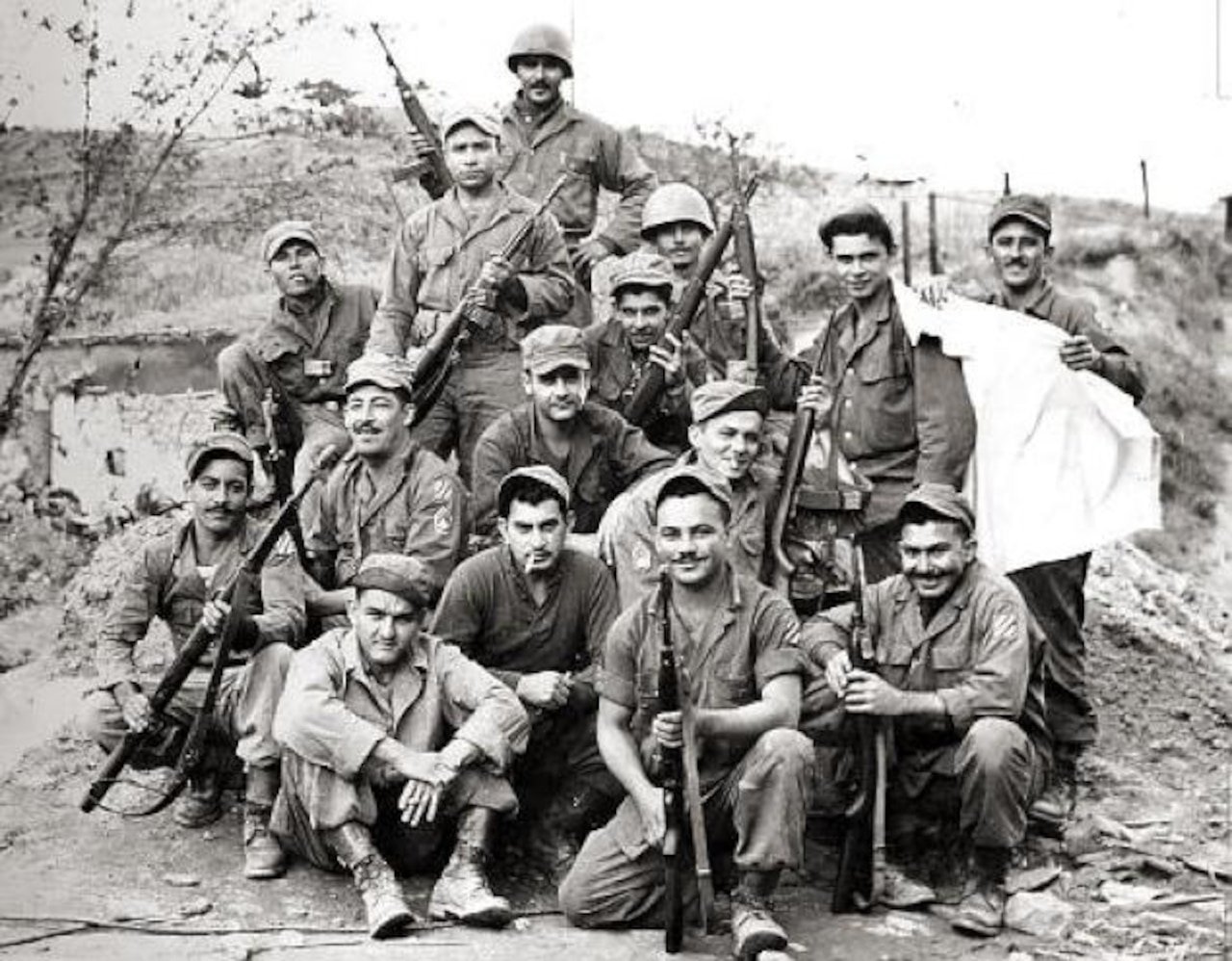

The Borinqueneers: the only all-Hispanic unit in US Army history Soldiers of the 65th, North of the Han River, Korea, June 1951. Photo courtesy of the US Army.

The men who served in the US Army’s 65th Infantry Regiment have something to be proud of. Known as the Puerto Rican Regiment prior to World War II, the last all-Hispanic unit in military history has overcome decades of severe racial prejudices and segregation since its formation in 1899. Their service and sacrifice was once ridiculed and mocked, despite their fighting and dying alongside their fellow Americans. The unfair treatment and status as outcasts led to the largest mass court-martial of the Korean War. Some 70 years since returning from battle, their legacy today is of recognition rather than anonymity.

These forgotten heroes from the forgotten war were described as “the Hispanic version of the Tuskegee Airmen.” While combat troops were engaged in trench warfare across war-torn Europe during World War I, these soldiers were sent to the Canal Zone in Panama for a non-combat related assignment. As the US entered World War II, nonwhite soldiers weren’t the first choice for front-line combat. Although members of the 65th’s ranks earned a Distinguished Service Cross, two Silver Star medals, and 90 Purple Heart medals, postwar downsizing threatened its existence.

The US military momentarily pondered whether or not to disband what they referred to as the 65th “Rum and Coca-Cola Soldiers” — another jab at their Hispanic heritage. In March 1950, “Operation Portrex” tested their mettle. The 65th had a challenging task as “aggressors” defending against an American force of 16,000 “liberators” who traveled aboard 150 naval vessels, hundreds of planes, and amphibious vehicles. Umpires of the Puerto Rican military exercise estimated if it had been, in fact, a real operation, nearly 50% of the liberating force would have been casualties.

Belonging to the 65th became a badge of honor, something to be celebrated among fellow Puerto Ricans. Through shared camaraderie and heritage, they dismissed their racial nicknames with disgust and adopted a new label as “The Borinqueneers.” The sobriquet is in appreciation of the Taino Indians, the natives from the island of Borinquen before it became known as Puerto Rico.

When North Korean troops crossed the 38th Parallel to invade South Korea, sparking the Korean War on June 25, 1950, the Borinqueneers were selected as front-line combat troops.

The Borinqueneers were attached to the US Army’s 3rd Infantry Division and participated in numerous legendary battles. After the surprise landings in Inchon, the Borinqueneers helped push North Korean forces deep into the snowy mountains. They were later instrumental in the evacuation of the US 8th Army who had been overrun and the 1st Marine Division who was surrounded at the port of Hungnam after the Chinese Army entered the war.

In January 1951, other battalions from the 65th were tasked to take three hills occupied by the Chinese 149th Division. On the morning of the third day, the Borinqueneers fixed bayonets and charged through the freezing hilltops as the communist Chinese soldiers fled.

“The Puerto Ricans forming the ranks of the gallant 65th Infantry give daily proof on the battlefields of Korea of their courage, determination and resolute will to victory, their invincible loyalty to the United States and their fervent devotion to those immutable principles of human relations which the Americans of the Continent and Puerto Rico have in common,” Gen. Douglas MacArthur wrote in 1951. “They are writing a brilliant record of heroism in battle and I am indeed proud to have them under my command. I wish that we could count on many more like them.”

A year of combat experience for the 65th in Korea resulted in 15,787 enemies killed in action, 2,169 prisoners of war taken, four Distinguished Service Cross medals, and 125 Silver Stars.

In September 1952, the 65th suffered 542 casualties at or near Outpost Kelly. Pvt. Sergio Lopez de Lopez was 23 years old when he was ordered to climb the hilltop. “Thirty-eight men went up,” he recalled. “Three came down.”

Again the members of the 65th were disgraced when their highest-ranking officer, Col. Juan Cesar Cordero Davila, was fired and replaced with an inexperienced combat leader in Col. Chester B. DeGavre. The white officer from West Point couldn’t speak Spanish nor did he try.

He stripped the 65th of their famous Borinqueneers name, rationed rice and beans, which was their custom food choice, and issued them signs to hang around their necks that read, “I am a coward.” The final straw that resulted in a mutiny was DeGavre’s order to shave their iconic mustaches that certified “manhood” in their heritage.

“Mine had to go also, after 22 years with me,” wrote Maj. Silvestre E. Ortiz, the regimental adjutant. “All that the mustache means to a Puerto Rican, it is part of his personality, in many cases the product of a religious vow, so much so that the three chaplains went to visit this gentleman and apprised him of its importance, unsuccessfully.”

Morale dropped and their friends were dying. Their new commanders didn’t care — they needed bodies to assault Jackson Heights, the exposed land in between the US and Chinese forces. With no artillery or air support, 80 Borinqueneers were mustered, but all refused because the operation was a suicide mission.

One account says 123 soldiers were court-martialed, while another suggested 162 — regardless, the members of the Borinqueneers faced sentences as lengthy as 18 years of hard labor. However, they were convicted to serve on average five years.

The soldiers of the 65th who stayed and fought at Outpost Harry went on to receive 14 Silver Star medals, 23 Bronze Stars for valor, and 67 Purple Hearts. In 2014, Master Sgt. Juan E. Negrón’s Distinguished Service Cross was upgraded to the Medal of Honor. He single-handedly defended a position in Kalma-Eri by hurling hand grenades and engaging in hand-to-hand combat. When reinforcements arrived, his position was littered with the bodies of 15 enemy combatants.

In 2016, Congress presented the 65th Infantry Regiment with the Congressional Gold Medal for those “who have performed an achievement that has an impact on American history and culture that is likely to be recognized as a major achievement in the recipient’s field long after the achievement.” Since 1776 when George Washington became the first recipient of the Congressional Gold Medal, only 169 other individuals or groups share the honor.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.