The Boston Tea Party: How Coffee Became the Official Morning Beverage of America

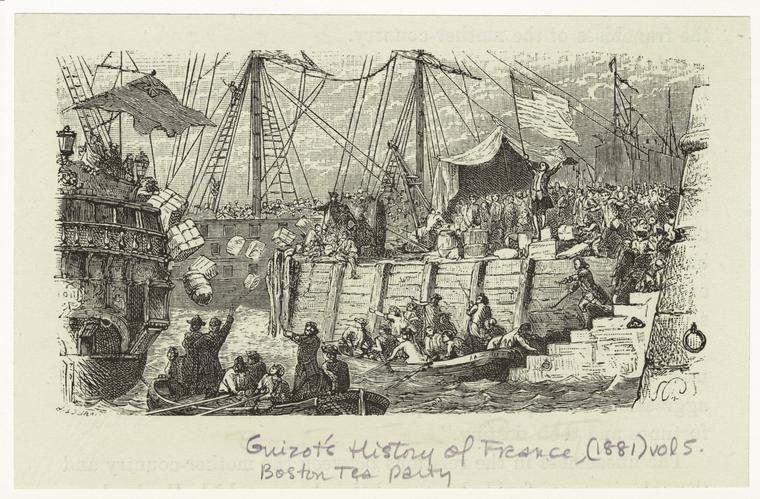

An artist’s rendering of the Boston Tea Party, Dec. 16, 1773. A group of Bostonians threw tea into Boston harbor as a protest against the British parliament’s Tea Act of May 1773. In actuality, the event occurred at night and with a minimum of fuss, despite artistic renderings to the contrary. Photo by MPI/Getty Images.

How does one start a revolution? It begins with a group of like-minded individuals who are bold enough to carry out an action against a superior entity, ultimately to change control of power. In the days of the American Revolution, these individuals were known as the Sons of Liberty, and their supporters — patriots like Sarah Bradlee Fulton, among others — predicated their success on secret preparation. How could they lead a rebellion against England’s powerful King George III and inspire townspeople to join their cause?

It didn’t happen overnight, but a series of events emboldened them to launch into action with an idea that was formed behind closed doors. It became known as the Boston Tea Party and is one of the most impactful political protests in history.

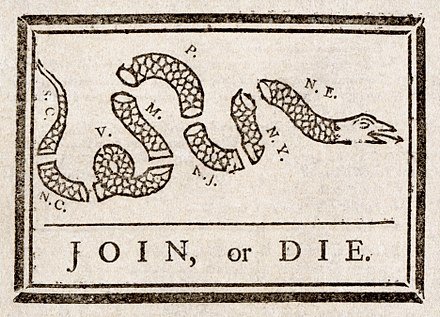

In the 1760s, the colonists living in Boston, Massachusetts, felt that the British were taking advantage of them. Benjamin Franklin, one of the Founding Fathers who later penned America’s first political cartoon under the namesake “Join, or Die,” saw firsthand the strength and influence of a unified people. He shared these observations about his displeasure with the British through the written word, including poetry:

We have an old mother that peevish is grown,

She snubs us like children that scarce walk alone;

She forgets we’re grown up and have sense of our own,

Which nobody can deny, which nobody can deny.

Meanwhile, Boston’s economy thrived; they had successful taverns, the richest shipyard on the waterfront, 3,000 wooden and brick homes, and some 500 shops. The population of 16,000 were hardworking and young — half of them were teenagers. The majority in Boston were educated enough to read the ever-popular Boston Gazette newspaper and follow updates on how the British bullied and used them as pawns to fund their wartime debts (from the French and Indian Wars).

In 1765, Parliament, England’s governing body of the colonies, imposed the Stamp Act, which taxed Americans for anything made from paper after it arrived in colonial shipping ports. The Quartering Act followed, which demanded that citizens open their businesses and homes to British soldiers for housing and food. Two years later, the Townshend Act added paint, glass, lead, and tea to the list of taxable goods.

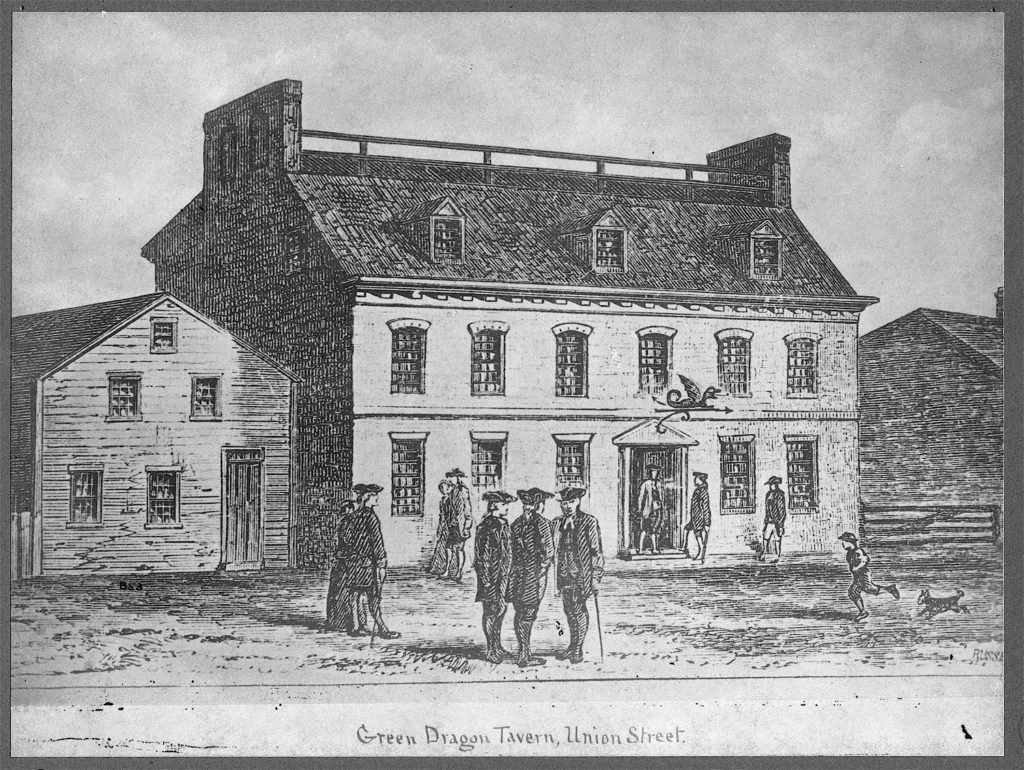

The American colonists were naturally angry, and tensions were consolidated to an upheaval in anarchy. By this time, the secret society of rebels known as the Sons of Liberty had formed. Frontman Samuel Adams — among other members such as John Adams, John Hancock, and Paul Revere — held public gatherings at Faneuil Hall to gain notoriety. In secret, the future Founding Fathers also held private meetings at the Green Dragon Tavern or the “House of the Revolution,” previously located on Union Street in Boston’s North End. Samuel Adams’ individual actions had the British publicly cast him as “the most dangerous man in Massachusetts.”

Their freedoms were being infringed upon, writes Kathleen Krull in her book “What Was The Boston Tea Party?” They protested in small boycotts and skirmishes against loyalist businesses (those who sided with the British), which made the headlines in the next day’s newspaper — but, most importantly, it caught the attention of the royal tyrants. Adams encouraged other patriots who believed in their cause to act in defiance. They used intimidation, vandalism, and even defamation of tax collectors through a shameful punishment called tarring and feathering.

On Feb. 22, 1770, one of these strong-armed attempts turned violent when British customs officer, Ebenezer Richardson, fired his musket upon a group in his backyard, killing 11-year-old Christopher Seider. A month later, on March 5, 1770, Private Hugh White, a British soldier, used his bayonet against a patriot at the Custom House on King Street.

White escalated the verbal altercation to a physical one, and the angry mob countered with a volley of snowballs, rocks, and ice. Bells rang signalling a disturbance, and loyalists and patriots entered the street to see the commotion. As the riot ensued, the British fired their muskets, killing five colonists in what is today known as the Boston Massacre.

After these two incidents of bloodshed, the final straw was the imposition of the Tea Act, which was passed in May 1773. The Sons of Liberty had illegally smuggled tea from Holland because anything associated with the British infuriated them. Parliament countered with the enforcement of the British East India Company, the only tea that could be purchased. The once-adored tea from India and China, all 18 million pounds of it, had been outcasted by the colonists. So a group of American women began to make their own.

Women also played important if lesser-known roles in the events leading up to the Boston Tea Party. Similar to the Sons of Liberty, a group comprised of approximately 300 women was referred to as the Daughters of Liberty, and they had significant influence. Sarah Bradlee Fulton was an important figure who became known as the “Mother of the Boston Tea Party”; she later became one of the first women to come under the orders of George Washington as a spy during the American Revolution.

Fulton’s role in the Boston Tea Party wasn’t the infamous actions of dumping tea into Boston Harbor — it was more subtle, though equally important. Fulton is credited with suggesting that the patriots wear disguises during their great tea-dumping campaign to ensure that they couldn’t be recognized from a distance and would remain incognito when they ditched their outfits after the event.

Colonists also spread propaganda about British tea in the newspapers, instead valuing “Liberty Tea” made by American women in homemade batches. “Let us abjure the poisonous baneful plant and its odious infusion,” wrote one colonist. “Poisonous and odious, I mean, not on account of the physical qualities but on account of the political diseases and death that are connected with every particle of it.”

The Liberty Tea used the red root bush herb found growing on riverbanks. Red sumac berries and homegrown leaves were used to make Indian Lemonade Tea. Other recipes meticulously crafted delicious Raspberry Leaf Tea. It was declared “as good as any other tea, and much more wholesome in the end.”

While the Daughters of Liberty generally voiced their dissatisfaction with the British in quieter ways, they occasionally had to get a little rowdy. One such incident involved a merchant who was hoarding coffee, which was later dubbed the “Coffee Party.” Abigail Adams wrote about it to her husband, John, on July 31, 1777.

“There has been much rout and noise in the town for several weeks. Some stores had been opened by a number of people and the coffee and sugar carried into the market and dealt out by pounds. It was rumoured that an eminent, wealthy, stingy merchant (who is a bachelor) had a hogshead of coffee in his store which he refused to sell to the committee under 6 shillings per pound. A number of females some say a hundred, some say more assembled with a cart and trucks, marched down to the warehouse and demanded the keys, which he refused to deliver, upon which one of them seized him by his neck and tossed him into the cart. Upon his finding no quarter he delivered the keys, when they tipped up the cart and discharged him, then opened the warehouse, hoisted out the coffee themselves, put it into the trucks and drove off. It was reported that he had a spanking among them, but this I believe was not true. A large concourse of men stood amazed silent spectators of the whole transaction.”

But what happened in Boston Harbor four years prior was a pivotal moment in the fight for American independence.

On Dec. 16, 1773, an assembly was called at the Old South Meeting House, the largest building in colonial Boston. This is where John Hancock made a passionate demand: “Let every man do what is right in his own eyes!” The historic meeting amassed an estimated 5,000 to 7,000 colonists unified together against tyranny. The Boston Tea Party was put into motion to resist British oppression and to rally against taxation without proper representation.

That evening, disguised as American Indians, “Adams’ Mohawks” marched toward Griffin’s Wharf carrying axes and tomahawks, wearing feathers on their caps and warpaint on their faces. The only opposition between the liberators and 342 chests of tea was a British officer who had drawn his sword. He was no match for them and simply stepped aside as he was heavily outnumbered. The men split into three groups and boarded the three ships: the Dartmouth, the Eleanor, and the Beaver. They ordered the crew below deck, then used ropes and pulleys to hoist 90- to 400-pound chests of tea up from the cargo area, onto the deck, and into the harbor.

A large crowd gathered on the shoreline and cheered on their patriots as they emptied the tea into the shallow harbor. With low tide, the harbor’s height was only two feet, therefore the “Indians” had to stomp the piles of overflowing tea leaves to get them to sink. Some of the raiding force tried to sneak tea into their pockets — one was even brave enough to use a rowboat to collect his stash, but these canoes were overturned. After they emptied all of the crates, enough to fill 18.5 million teacups, the “Indians” ducked into safe houses, through the help of the Daughters of Liberty, and were home by 10 that night.

John Andrews, an observer, later wrote, “They say the actors were Indians… Whether they were or not to a transient observer they appear’d as such, being cloth’d in blankets with the heads muffled and copper color’d countenances, each being arm’d with a hatchet or ax, and pair pistols, nor was their dialect different from what I conceive these [sic] geniusses to speak, as their jargon was unintelligible to all but themselves.”

To this day, due to a pledge of secrecy, it remains unclear of who was directly involved in the historic action of dumping tea into Boston Harbor. But the event — known now as the Boston Tea Party — has become one of the most iconic events of the American Revolution, igniting a revolt against British rule and the beginning of a new unified nation.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.