The Female War Reporter Who Parachuted Into Vietnam With French Commandos

The humor in suffering is almost always pondered after the fact in memories — but sometimes it’s the little thoughts that creep in that provide a sense of solace in the surreal moment we are living. For Brigitte Friang, the underground French Resistance fighter and journalist who covered four wars across three decades, dark humor was her secret sauce in overcoming hardship. The petite “leading lady” parachutist had a cowboy persona and didn’t take “no” for an answer from bureaucratic, career-driven officers looking for their next promotion.

Friang was also the author of nine books, and she brought a ground-level view of the battlefield. She lived with spunk and wrote with moxie as she described environments that casted humanity against one another. Friang received accolades in every chapter of her life, but her most notable achievements occurred in the moment presented with raw authenticity. She was a visionary who captured emotions and put them into words the reader could digest. Her experiences in the “war before the war” are a historic account of the commandos among whom she lived.

Vive la résistance!

In 1943, Friang’s aspirations were in England, where she envisioned training to become a paratrooper. Instead, she was recruited in France as a P2 — permanent agent — where at night she decoded London-based telegrams collected from various radio-reception centers and sent them to liaison officers.

The busy 19-year-old had studied medicine in Paris prior to the war, but the French Resistance asked more of her. She worked from sun up to sun down organizing “dead drops” and transporting parachutists to safe houses. “By day I scurried from rendezvous to rendezvous; twice-daily contacts with the radio-liaison people, routine contacts with members forming our link with regional chiefs, with other groups and networks acting in cooperation with us, or those dependent upon us for agents or supplies, or using us as a stepping stone to London for a courier or an agent,” Friang wrote in her memoir, “Parachutes and Petticoats.”

She adopted a callsign, “Galilée II” (second to her network chief), and had a cover story armed with excuses in case she was questioned on the street by the Gestapo. Friends inside her network disappeared, and they were assumed to be captured or dead. The stress of being found out or discovered had apparent realities.

“In the 1940s, we still had the weakness of paying less attention to a woman and a man meeting, in the road, in a restaurant, in trains, than two men meeting.”

Friang felt the outside pressure and planned to meet with the liaison agent for “Shelley,” or Colonel Yeo-Thomas, the world-famous escape artist from the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), who the Germans called the “White Rabbit.” It was March 1944 and the meeting was scheduled for 10 AM in the gardens of Chaillot Palace near the Aquarium entrance. “In the 1940s, we still had the weakness of paying less attention to a woman and a man meeting, in the road, in a restaurant, in trains, than two men meeting,” Friang wrote, although the Gestapo later suspected everyone.

The meeting involved the discussion and plans to use German uniforms to smuggle Pierre Brossolette, a French journalist and resistance fighter, out of Rennes prison. The Gestapo were tough to spot but some wore civilian clothes with soft brown hats. As she approached her rendezvous, an instinct to escape rushed through her body. She was tackled to the ground in a flash. Voices demanded to see her papers, but her mind could only think of getting away. She broke loose and sprinted as gunshots rang out.

An unparalleled force lifted her off her feet and to the ground — she’d been hit. A Gestapo officer came up to her and spoke while inspecting the damage. “I’m sorry, Matame, it was such a big-caliber gun, but this is war,” he said. She couldn’t help but laugh, the dark humor in her situation prevailed. He’d apologized not for shooting her but for the type of gun he used. “Thanks — I’m aware of it,” she quipped.

They sent her to Fresnes, a prison where suspected commandos and resistance fighters were tortured. The Gestapo interrogated her for hours, poking her gunshot wound to get a response. Any plea for medicine was denied because, they callously reasoned, “No aspirin for terrorists.” Although the prisoners were isolated in single-person cells, they used the ventilation system to communicate. Friang reassured the “White Rabbit” that she had not given him up as she heard his voice come through the vents. Other voices chimed in to provide hope in the hopeless situation.

Those who didn’t talk during interrogation were sent away or killed. Friang was transferred to Ravensbrück, a Nazi concentration camp for women, which also housed the training ground for female Nazi SS officers. Another round of torture and a bout of tuberculosis tested her mettle as one SS doctor deemed she had only one week to live.

In April 1945, Friang death marched 300 miles from Ravensbrück to Dachau alongside 1,700 other female inmates. Only 200 women survived the journey. Following their liberation, Friang’s gradually recovered back in Paris — a far cry from her skin-and-bone, 57-pound appearance.

In April 1945, Friang death marched 300 miles from Ravensbrück to Dachau alongside 1,700 other female inmates. Only 200 women survived the journey.

Those in France who weren’t deported didn’t understand the stories of torture because years of German propaganda had dismissed any mistreatment. “Psychologically, the camp now seems to be an experience of someone else, whose existence has passed away,” Friang noted. “Without this burying, even if it was superficial, coming back to life would have been difficult.”

This war didn’t allow her to fulfill her dream of becoming a parachutist, but an opportunity in Indochina presented itself.

The War Before The War

Many countries had to rebuild post-World War II, and France used rice and opium fields in its colonies in Indochina as financial aid. When France refused to recognize Vietnam’s independence, the First Indochina War broke out between the French and the Viet Minh, the rebel army of Ho Chi Minh. The world’s superpowers took sides; the U.S. sided with France and sent American advisors to what was later called “the war before the war,” while China and Russia supported the Viet Minh and their communist ideals.

Friang worked as the first press officer of André Malraux for four years to learn the tools to the trade in media. She arrived in Saigon on Oct. 27, 1951, to cover the conflict in Indochina for the Samedi-Soir as a special correspondent. She envisioned exploring the faces of the gods at Angkor and the royal palace of Huế encircled by the citadel.

Her first stories were of the day-to-day lifestyles of those living in Hanoi and Saigon, and the deterioration of peace in the region. She linked up with the “red berets,” or French paratroopers (paras), and sludged through mud and elephant grass on taxing ground operations. They avoided landmines and indirect fire while the paras offered sarcastic and harmless remarks at Friang’s expense. Although the paras were weary of the pint-sized European, her quick-witted jabs helped her charm her way onto the team.

On one patrol, the paras stumbled across a Viet cinematograph camera as they were returning to base. Friang jumped at the chance for a joke. “Tell him [Verville] you’ve also captured a member of Uncle Ho’s Press Service,” she instructed. “That’ll be me, then you present the prisoner. It ought to be funny.” Verville watched the paras deliver their new prisoner to two others along the beach and prepared to confront the man. “He’s wearing jumping gear […] why! […] It’s Brigitte!”

Les Fleurs Du Ciel (The flowers of the sky)

Friang’s initial requests to participate in airborne operations were denied by officers from the 1st BPVN, also known as the French-Vietnamese Parachute Battalion, but like any persistent journalist, she gained access. Her intuition annoyed “chairborne warriors” but impressed seasoned spooks, which was evidenced by an exchange between the head of SPI, Major Gardes of the Tirailleurs. “You’ve ought to work for intelligence, not the press,” he said. “You know as well as I do there isn’t so much difference,” Friang countered.

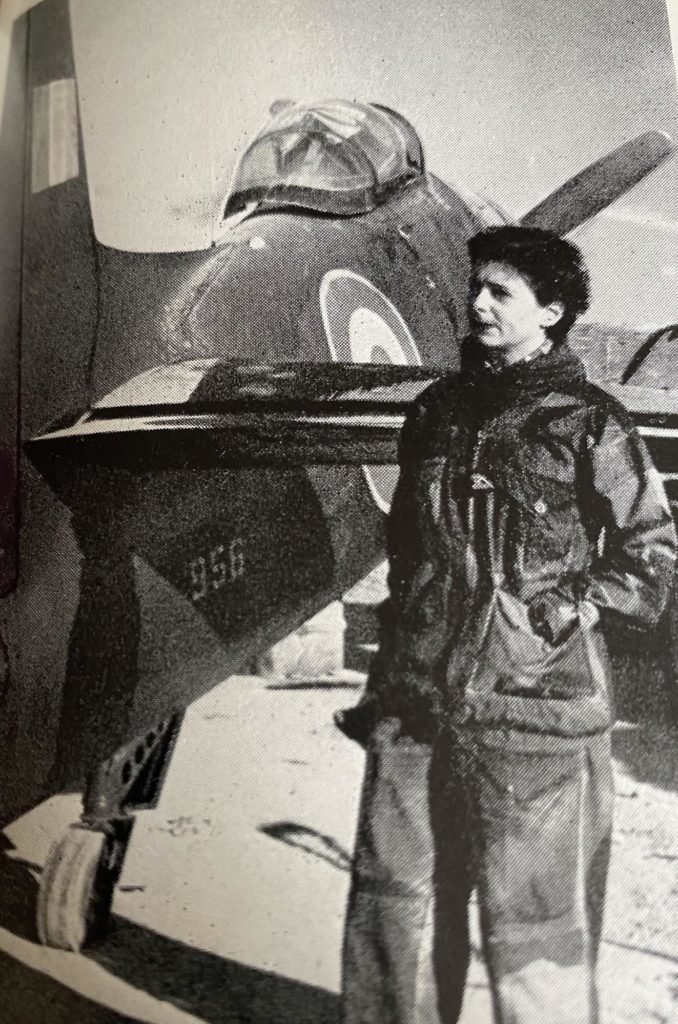

The paras questioned amongst themselves why a journalist would volunteer for such a difficult duty, but all opinions of her intent evaporated once she completed her first jump on a mission. She “death dived” headfirst, and the paras watched the second stick’s “leading lady” leap out of the plane. Her canopy settled in the grass, and “the boys ran up from all sides, shouting: ‘Bravo! […] Wizard! […] First Class! […] (they couldn’t have seen my exit).”

The paras were typically accompanied by Vietnamese, who Friang described as having cat-like falling abilities because no matter how bad a landing looked, they’d spring to their feet. In after action reports with their French counterparts, the Vietnamese referred to Friang [Missy or Mademoiselle] as if she was a map reference: “We received contact by Missy here,” or “we found a landmine east of Missy there,” and so forth. Once back at the command post in the field, other paras from 3rd BPVA gawked at the “parachute girl,” surprised to see a woman dressed in combat boots, jumping gear, and fatigues.

During her down time she searched for the next airborne operation. While newsreel men, photographers, and other press traveled by boat or by helicopter, she went by parachute. There was one occasion, however, when she hitched a ride aboard a navy vessel en route for Saigon. The next day, Admiral Auboyneau of the French Navy was furious because she didn’t receive official approval. She reasoned that once they invented a way to parachute back up into a plane, then she would “continue to embark along with the troops with whom she had been dropped.” The admiral had the final say by banning all journalists on naval vessels unless they received proper clearance.

Aside from her jumping wanderlust, Friang chronicled elements of war that aren’t typically explored in movies. She wrote of Bli Tcheu, “the Son of Cats,” a Lao guerilla sympathetic to the French, and his helpless fight against Vo Nguyen Giap, the battlefield genius who later led the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) against the Americans during the Tet Offensive. She shared the daily misfortunes of soldiers losing their wits, friendly fire incidents, and sensational operations. She penned articles about Captain Valérie André, the woman flight surgeon and helicopter pilot. She documented instances of anti-smuggling campaigns, visited coal mines, and even took a poll of North Vietnamese intellectuals.

She wrote about whatever drew her interest. Sometimes she shared lighter perspectives, including how all the soldiers perceived the only woman in their camp.

Friang observed soldiers walking by her makeshift tent, which was made entirely from parachutes, and some not turning their heads until they bumped into something. She described the randomness of multi-day operations with the paras. The supply drops almost always guaranteed at least one “Roman Candle,” or parachute that failed to open. Each commando groaned as they assumed it was the booze — and, sure enough, it was the wine.

Whenever Friang rejoined the battalion of paras after she was off somewhere else, they knew an airborne operation was in the works. Friang’s reputation was sealed when she showed up to the airfield to participate in Operation Castor, the largest airborne operation of the First Indochina War. From Nov. 20 to 22, 1953, six French airborne battalions and support troops parachuted over the valley of Dien-Bien-Phu.

Inside the plane overhead, any pre-jump jitters had faded as at this time Friang already had half a dozen combat jumps under her belt. The seasoned vet calmed her nerves by pulling out a copy of “Le Monde” and a nail file, much to the amusement of the battle-hardened commandos. Once on the ground, the press received telegrams to report to Laos to cover the Franco-Laotian advancement. Again, wherever she went as a female reporter, she had a tug-of-war match against every new officer.

Colonel Fourcade presented another battle for Friang when he suggested she take a helicopter to Laos instead of jumping with the soldiers. “The battalions are jealous if the reporters make too many operational jumps,” he told Captain de Lassus, Friang’s friend and a fellow parachutist. “You see, if Brigitte makes too many jumps, it lowers the paras’ prestige.”

As she had done previously, Friang used her contacts within the para community to vouch for her as long as she could secure an airplane, a dispatcher (jumpmaster), and a parachute.

The seasoned vet calmed her nerves by pulling out a copy of “Le Monde” and a nail file, much to the amusement of the battle-hardened commandos.

When she got all three, she was up in the air — and then back on the ground again — in no time. Except on this occasion she was hung up in thick vegetation in the Laotian mountains outside of a foreign dropzone. It took several Laos soldiers to untangle her and return to the command post. They were surrounded by the Viets and couldn’t light as much as a campfire out of fear of being targeted by mortar teams along the outskirts.

When she saw a familiar face, she amused them by donning her “model reporter’s outfit,” which always brought smiles. “Do you know what pleased the boys most and gave them the biggest surprise?” asked General Cogny, one of the officers she was attached to at the hip. “It wasn’t seeing you drop into the middle of the mountains. It was seeing you appear later with rouge on your lips.”

Friang celebrated her Christmas of 1953 and the 1954 New Year in Dien-Bien-Phu, where for two months she camped out with the men in foxholes withering the weather with little supplies. On Jan. 23, 1954, Friang turned 30, and the paras gifted her a cake with a lone candle, a noble gesture from an officer and gentlemen. When they consumed their sweets, they gifted her a massive 102 shell decorated with funny drawings and the inscription “Happy Birthday, Brigitte!” wrapped in a rosette.

During the month of March she was working in Hanoi and just missed the Battle of Dien-Bien-Phu, an all-out assault launched by the Vietminh on March 13, 1954. The stronghold of Beatrice fell within hours, and the bloody 56-day battle decided the fate of the French.

On June 6, 1954, about a month after she returned from the First Indochina War, she appeared on the television game show “What’s My Line?” Decades of wartime traumas were hidden behind a bubbly personality. The panel struggled to guess her career but were marveled when it was finally revealed.

The feisty journalist didn’t give up her war pursuits and ventured across the globe with a pen in her hand. She authored eight additional books and wrote articles on the Suez Expedition in 1956, accompanied Israeli troops into Jordan and Syria during the Six Day War, and returned to Vietnam to write daily dispatches of the Tet Offensive in 1968. Always a step away from danger, the Viet Cong captured her on two separate occasions, but she was released without harm both times.

Brigitte Friang may not have looked the part, but she surprised nearly every doubter in her path. In March 2011, she died at 87 years old. Her spirit remains a motivation for future generations of female journalists to live out their dreams despite the obstacles. When others refused, she continued to ask why.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.