The Buffalo Soldier Olympian Whom Patton Called the ‘Best Goddamned Athlete I’ve Ever Seen’

Olympians Jack Davis, left, Harrison Dillard, center, and Arthur Barnard, right, pose with their medals after the 110-meter hurdles race at the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki, Finland. Dillard won gold while his teammates took home silver and bronze medals. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Harrison Dillard arrived at the 1948 Summer Olympics — the first Olympics since the 1936 Berlin Games — prepared to run. The remnants of the war in Europe remained, while life moved on in its wake. The composition of the track surface at Wembley Stadium in London contained bomb rubble ground to a powder and blended with the sand and clay.

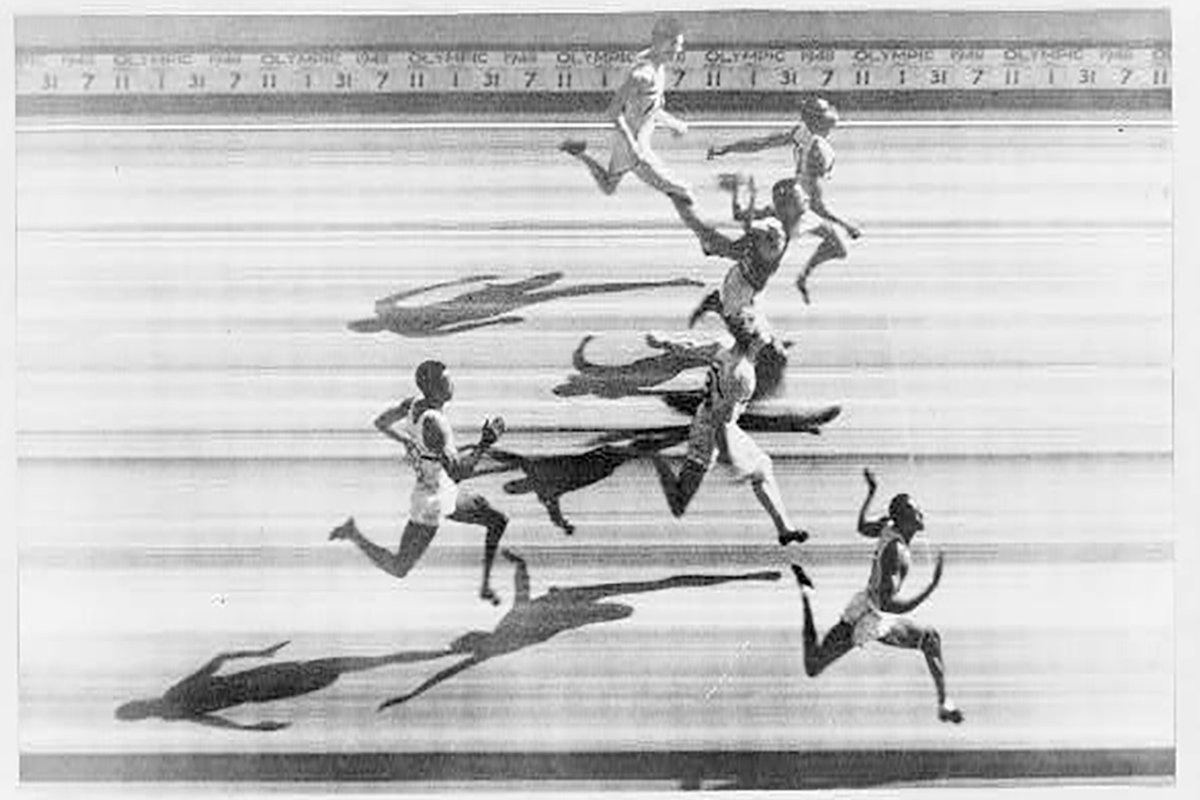

Dillard, a World War II veteran, took his position, crouching next to five sprinters for the 100-meter dash finals. The gun fired, and 10.3 seconds later, the race was over. Dillard won in a photo finish — an Olympic first.

It was Dillard’s first of four total Olympic gold medals won in 1948 and 1952. Dillard is the only male athlete ever to win Olympic gold medals in both the 100-meter dash and the 110-meter hurdles. As the years went on, though, newer runners received the honorary title of “fastest man alive.” The gold medals Dillard earned were kept stashed away in the closet of his suburban home in Cleveland.

His subsequent career, as a scout for the Cleveland Indians (now called the Cleveland Guardians) baseball team and then as a business office manager in the Cleveland City School District, proved the veteran had more to contribute to his country than Olympic glory or battlefield service. Still, in the years before his death in 2019, Dillard shared some of his fondest memories, many of which came from before he was famous, including literally chasing in the footsteps of childhood hero and fellow Olympian Jesse Owens and earning the praise of Gen. George S. Patton at the “GI Olympics” in postwar Germany.

One of Dillard’s favorite moments came in 1933, when he was 9 years old. Owens, who was in his senior year in high school, was already a track and field prodigy. Dillard and his childhood friends arrived at an indoor track meet at East Technical High School in Cleveland, Ohio, to watch Owens race.

“Wiggling and squirming our way through the crowd, we got in the position where we could see the youth who was going to become our idol,” Dillard wrote in the Cleveland Press in 1980 after Owens died, according to The Undefeated. “He was preparing for an attempt at the high jump. He was lean and lithe, with skin the color of coffee with cream. I watched wide-eyed as he glided up to the bar, leaped and slid over it easily in the effortless manner that has never been equaled to this day.”

Three short years later, Owens won four gold medals in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, humiliating Nazi leader Adolf Hitler in the process. Dillard attended the same high school as Owens, running laps in the same tiny “squirrel cage” gym as Owens once did, believing that one day he, too, could race in the Olympics.

Dillard went to Baldwin-Wallace College (now called Baldwin Wallace University) on a track scholarship. However, during his sophomore season in 1943, he was drafted into the US Army. He was assigned to the 370th Infantry Regiment, 92nd Infantry Division — an outfit known as the Buffalo Soldiers. They were the only segregated African American infantry division to see combat in Europe, fighting in the Italian campaign during World War II.

In 1944, Dillard, who was by then a private first class, and the Buffalo Soldiers entered combat in Italy at Viareggio. The unit slowly advanced north and liberated Italian towns in the Po Valley and the Apennines. For six months, Dillard dodged mortar and artillery fire and stayed clear of enemy minefields. About three weeks before the war ended, however, Dillard experienced the hard realities of racism and discrimination, which remained prevalent during the war, no matter one’s location. Many townspeople in an Italian mountain village closed their doors and blocked their windows when they heard from a battalion of American soldiers that the approaching Black soldiers would harm the women and children.

The unusual part, as Dillard said in an interview, was that “at the same time, we’re fighting right next to each other.” For some soldiers, the more than 12,000 military decorations and citations the Buffalo Soldiers received weren’t enough to break down preexisting stereotypes.

After the Nazis surrendered and the war in Europe was over, Dillard took a plane from Italy to Frankfurt, Germany. He was invited to compete in the “GI Olympics” — a sporting competition in which troops from the Mediterranean theater competed against troops from the European theater. Overseeing the competition was Patton, the legendary Army general and a former Olympian in his own right, having competed in the modern pentathlon during the 1912 Games. Dillard took home three or four first-place finishes while Patton looked on in amazement.

When reporters from Stars and Stripes asked Patton what he thought about the performance of the young private first class, the general famously replied, “He’s the best goddamned athlete I’ve ever seen.”

Dillard, who credited the Army with keeping him in tiptop shape, was ultimately inducted into the US Olympic & Paralympic Hall of Fame.

Read Next:

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.