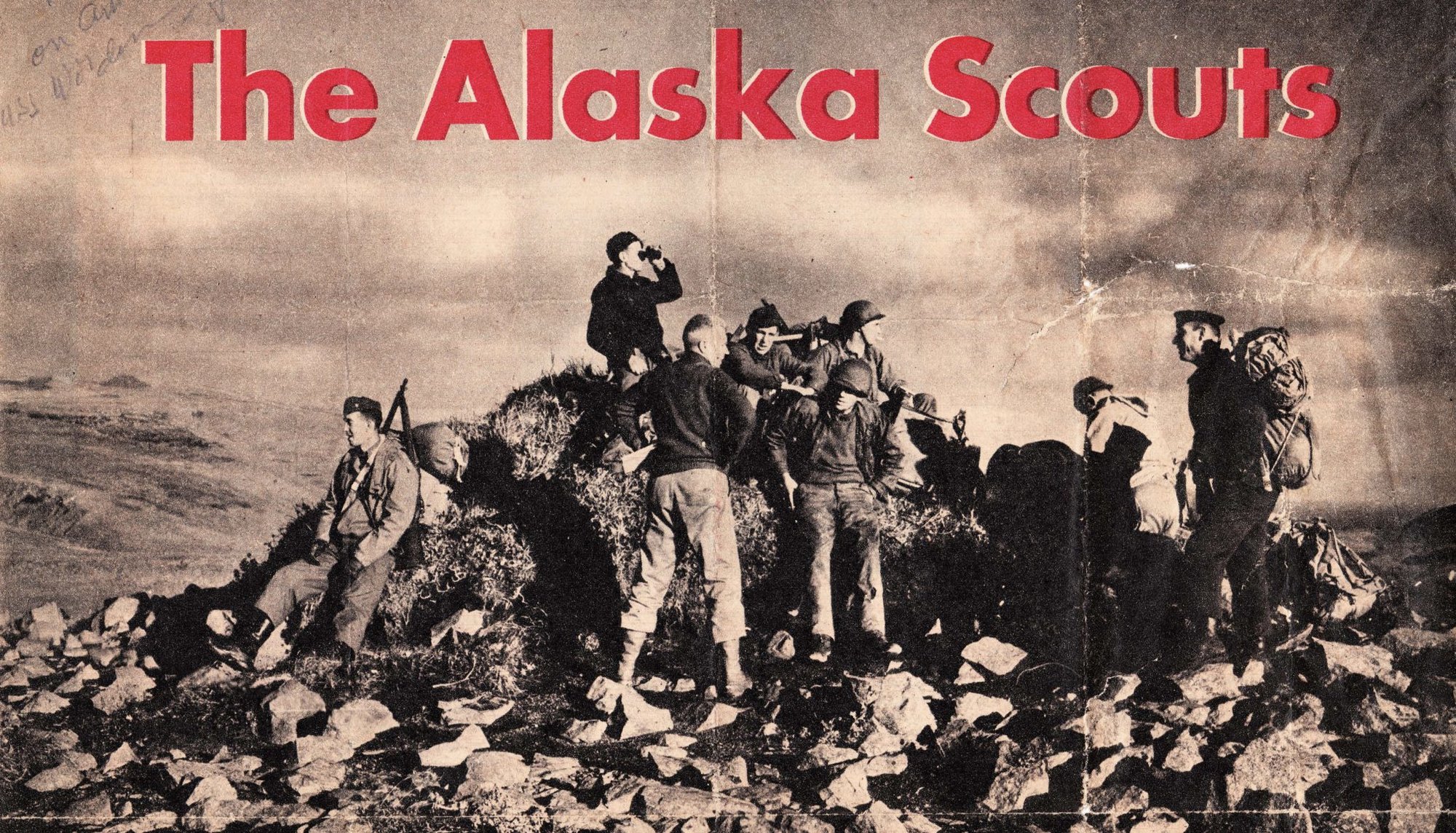

The Alaska Scouts were established Nov. 19, 1941, weeks before the attacks on Pearl Harbor. Photo courtesy of natesalaskanadventure.com.

“I believe that, in the future, whoever holds Alaska will hold the world,” Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell said in his last public appearance in 1935. “I think it is the most important strategic place in the world.”

That insight from “the father of the US Air Force” proved prescient less than a decade later. In World War II, the Japanese forces believed Alaska’s Aleutian Islands could provide them with a huge strategic advantage. The Japanese hoped that holding the chain of islands would both prevent the US Navy from reaching the islands of the South Pacific and provide airfields for launching bomber attacks against Seattle and other US targets.

In Alaska, which was a US territory at the time, a young Army soldier recognized the potential danger and knew the territory was woefully unprepared. Maj. Lawrence Varsi Castner was an intelligence officer assigned to the Alaska Defense Command in 1940. He argued for the need for a special commando force to defend the Alaska Territory in the event it was attacked. Following the Spanish-American War, Castner’s father had fought with a legendary Indigenous force: the Tagalog Scouts in the Philippines. Castner wanted to establish a similar force in Alaska.

He needed the very best Alaska had to offer. The cold, wet terrain of the Aleutians was beyond the experience of almost all US troops. The Aleutians are a broken chain of craggy volcanic islands in the northern Pacific — on the same northern latitude as places like Quebec and Amsterdam — with rocky coasts and high mountains, all regularly raked by vicious weather from the Bering Sea.

Castner formed the Alaska Scouts — nicknamed “Castner’s Cutthroats,” though they preferred to be called “Alaska Scouts” — from a collection of Alaskan trappers, hunting guides, commercial fishermen, miners, prospectors, and many Alaska Natives. The Alaska Scouts officially became the 1st Combat Intelligence Platoon on Nov. 19, 1941, weeks before the surprise attacks on Pearl Harbor.

“We’re a punk-looking outfit,” Alaska Scout Larry Beloff said. “I guess the Army never saw anything like us before. When the colonel picked us out, the brass hats took one look and threw up their hands.” Beloff, the owner of two gold mines in Alaska, was known as “Diamond Jim” because he wore a diamond ring and a diamond-studded watch wherever he went. Beloff and the rest of that band of misfits neglected to wear insignia so as not to expose their ranks in the event they contacted the enemy.

They had the skills to operate in the Alaskan backcountry and carried their own provisions. They caught fish and crabs for food. The idea was to survive without resupply or personal contact with the outside world as they conducted operations, scouting for enemy forces. Maj. William J. Verbeck, an officer who earned three Silver Stars in the later years of World War II, taught them how to fight like commandos. Some carried the Browning Automatic Rifle, capable of firing 20 rounds per magazine, while others used the M1 Garand for its lighter recoil. The Alaska Scouts valued personal choice and used .22-caliber rifles, hunting knives, and even sidearms.

“I really gave those boys hell,” Verbeck told staff correspondent Sgt. Georg N. Meyers of Yank: The Army Weekly. “Fifteen hours a day. Hardening marches through the snow out in the woods. Sketching and map making. Day after day of shooting every weapon a man can carry over his shoulder or on his back.”

The unit had fewer than 100 men and was prepared for battle. Following Pearl Harbor, the attack Castner had believed was coming did indeed arrive, and it did so in full force. Japanese Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto intended to “invade and occupy strategic points in the Western Aleutians.”

After US intelligence broke the Japanese naval code, Adm. Chester Nimitz decided to attack both the enemy fleet heading for Midway and the one attacking the Aleutians, ordering Rear Adm. Robert A. Theobald to defend Alaska at all costs and hold Dutch Harbor, a small naval facility and fishing village in the eastern Aleutians.

The Scouts’ initial secret landing was on Adak, an unmapped island in the central Aleutians. On the night of Aug. 28, 1942, two US submarines surfaced, and 37 Scouts in five rubber rafts paddled through 4 miles of chilly water to reach the shore. They faced no resistance and set up an airstrip. Soon after, they built a second airstrip on the island of Amchitka, from which American planes began bombing Kiska.

The main push to recapture frigid Attu Island occurred just as US forces began the “island hopping” campaign in the tropical South Pacific. For comparison, Marines on Guadalcanal and Tulagi battled shirtless in jungles that weather reports of the time said averaged in the high 80s with humidity. Meanwhile, the troops in Attu faced tall mountain passes and temperature averages as low as the 30s, with routine bursts of icy rain driven by winds that could reach 100 mph.

On May 11, 1943, Scout units guided some 15,000 Allied troops onto the beaches of Attu to retake the island from more than 2,300 fortified Japanese soldiers. The landings at Holtz Bay were led by Lt. Robert H. Thompson, who had been a skier in college. Thompson led a 25-member group onto Scarlet Beach to spot defenses and select a preferred landing spot for the main force. He was in the first boat to touch land, and 100 feet inland was a low bank, 2 feet high.

“I reached it as fast as I could just in case there was a Japanese soldier waiting to dispute my right to be there,” he recalled. “By the morning of the second day the fog had lifted, covering only the ridge tops where the enemy had dug in. They could see us; we couldn’t see them. We were given the job of probing fog banks, working our way forward till we drew fire. On one of those trips I got a bullet in my collar.”

Some of the Cutthroats weren’t as lucky. At Massacre Bay, an inlet on the southeastern coast of Attu, Sgt. Clyde Peters accompanied the regimental commander Col. Edward Earle in the first wave. The Japanese defenders spotted them and ambushed them.

“Col. Earle was killed by mortar fragments,” Yank reads. “Peters, with 11 bullet wounds, was lugged to the beach by sweating medics, and the Scouts never saw him again.” Everyone believed he had been killed in action until they received a letter from him mailed from a California hospital.

The battle raged for most of May as the Army slowly pinned the reduced Japanese forces. The remaining Japanese soldiers weren’t going to allow themselves to be taken alive, though. “Our job was really finished,” Cpl. Raymond Conrad told Yank.

On May 29, the commander of the dwindling forces, Col. Yasuyo Yamasaki, ordered his troops to fix bayonets and form a charge. To the surprise and horror of the pursuing Americans, Yamasaki ordered his 800 remaining troops to charge and fight to the death in the only WWII banzai charge on American soil.

“We had already located the enemy’s general whereabouts for the Infantry, but [Cpl. Edward] Bagby and I went along for the hell of it,” Conrad said. The pair were witnesses to suicides in which Japanese soldiers pulled the pins on their hand grenades and waited for the detonation. They each received the Silver Star for killing eight Japanese soldiers in a 90-minute point-blank firefight that included the use of their own hand grenades.

In the final battle, only 29 Japanese soldiers were taken prisoner.

The American casualties were 549 soldiers killed, 1,148 wounded, and more than 2,000 incapacitated by disease or cold-weather-related injuries.

Read Next: Watch: ‘The Men With Green Faces’ Vietnam War Navy SEAL Documentary

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.