Chasing the Dragon: A Combat Veteran’s Search for Healing in Central America

View from the airplane over Guatemala. Photo courtesy of Justin Governale, composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

The air was humid, and the bar in Jacó was full of insta-nomads trying to dry-hump each other to Wiz Khalifa. I was already over it. I had just flown into San José earlier that day to escape the suffocating normalcy that was overwhelming my life one day at a time, but watching bros pass joints and wannabe Miley Cyruses twerk to club hits from five years ago wasn’t doing it for me.

Twenty-two-year-old me would have loved it there. Halfway-to-70 me hated it. I needed more than fist pumps and body shots to get out of the funk created by COVID and the fog of mundanity that followed it. I needed something — anything.

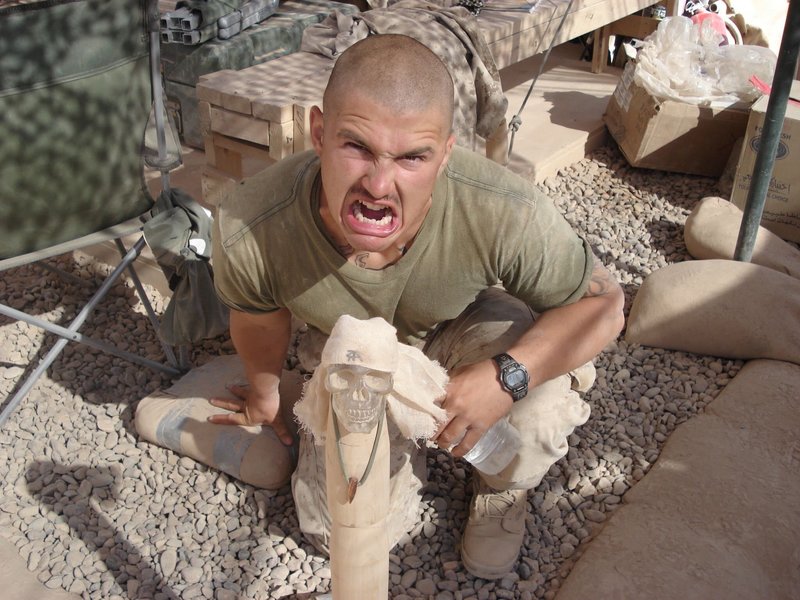

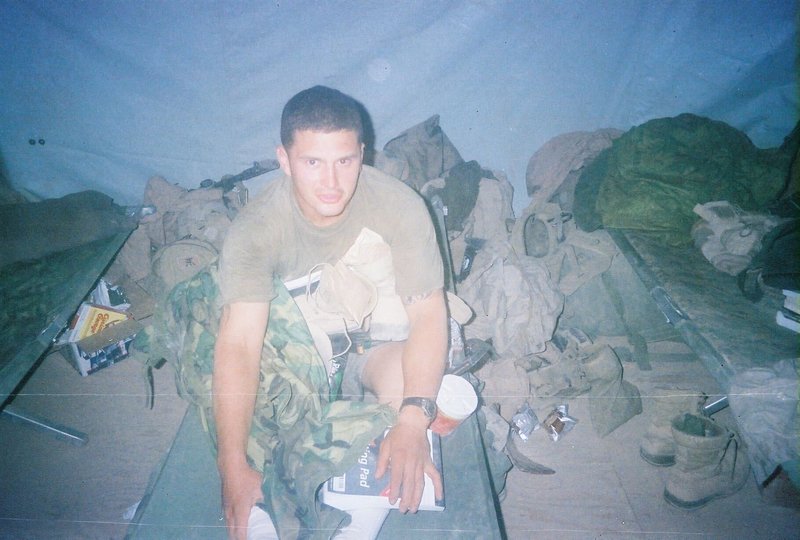

I used to be a US Marine Corps scout sniper. I’ve been to Iraq and Afghanistan multiple times. I’ve been shot at, shot back, and blown up three times. I’ve lived in Thailand, traveled to 27 countries, and fought professionally in a cage from time to time. Despite all that, I couldn’t escape the feeling of succumbing to normalcy.

So I left the States on a one-way ticket with nothing but three shirts, a pair of shorts, and a change of socks and underwear in my backpack. I arrived in Costa Rica with no plan outside of somehow getting to Guadalajara, Mexico, in two weeks. I was anxious about the unknown but knew I needed to punch the adrenaline button.

The author teaches a class in Tamarindo, Costa Rica, at the Tamarindo Jiu Jitsu Academy. Photo courtesy of Justin Governale.

I needed to chase the dragon, a phrase that heroin addicts use to describe their drug addiction, and that veterans use to describe their adrenaline addiction.

I walked out of the airport and into the heat and humidity. A gaggle of taxi drivers nearby were nearly fist-fighting each other over who was going to drive me to the hotel … a hotel I didn’t even have yet. I was on edge but kept walking until I saw a free hotel shuttle waiting at the curb, half-full but stiflingly hot with no air conditioning and its door open. I had no idea how far the hotel this shuttle belonged to would be from the airport, so I hoped for the best and sat down.

Once we arrived at the Marriott safely and quickly, a concierge attempted to engage me, but I politely brushed him off as I pulled up the Uber app on my phone. I ordered a ride to Jacó.

“Bryan” arrived in a small, red four-door Toyota with an Uber placard on the windshield. He hopped out with a smile and offered to take my backpack. I declined, and Bryan opened the rear door without skipping a beat.

“Prefiero una mejor vista,” I said, smiling.

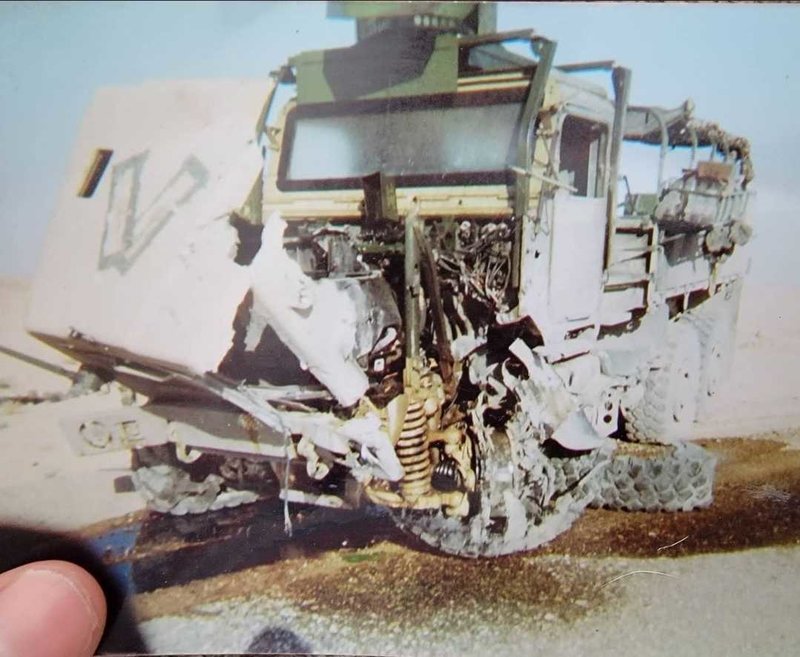

A truck from the author’s first patrol in Iraq, 2005, when he earned a Purple Heart. Photo courtesy of Justin Governale.

Bryan motioned me to follow him to the front of the car, inviting me to sit in the passenger seat next to him with genuine enthusiasm. I thought about telling him it wasn’t necessary to open the door for me, but I ended up taking the seat and letting him do his thing. He seemed to enjoy it.

“Gracias, amigo,” I said. “So Jacó, this is a long drive?”

“Sí. But if you cancel your ride on the app, I can give much better cash rate.”

I didn’t immediately respond, unsure if this was a scam. Bryan could sense my hesitancy.

“No, it’s okay,” he explained. “Jacó is two hours, and Uber is expensive. I can give you much better cash rate.”

I had the cash, but the cost of an Uber wasn’t the issue. If anything, Uber’s ability to track my movements would provide the comfort of knowing they’d probably find my body if something went wrong. Bryan sat across from me in the driver’s seat, his cheerfulness overshadowed by doubt.

“Cuánto?” I asked.

His smile returned. “For you, I give you friends and family rate. Fifty dollars.”

Fifty dollars was cheaper than Uber was quoting me by a considerable margin. I nodded, and Bryan pulled away from the curb as I canceled the ride request.

I got a full view of the beautiful Central American countryside. Maybe things would turn out okay on this trip? Too early to tell.

We talked, mainly in Spanish, some in English, all the way to Jacó. He was curious about how I knew Spanish and was surprised when I told him I was half Mexican and that my mom raised me speaking Spanish as a child. After we arrived in Jacó, Bryan pulled up to a hotel popular with travelers, told me that his side hustle was running a private taxi for tourists around Costa Rica, and gave me his card.

“Pura vida!”

I sat, looking at Bryan’s card as I finished my second beer at the bar in Jacó, yet again surrounded by rich kids on perpetual spring break. The scene was about as far from “pura vida” as possible. Lose the obvious vacation destination and accompanying bar staff; the same scene could be playing out in any bar from Tampa to San Diego. I had nothing in common with the other travelers around me, and frankly, I hadn’t flown down here to get hammered and contract chlamydia on my first night. Maybe on the third night, but definitely not my first. I paid the tab, put Bryan’s card back in my pocket, and returned to the hotel.

I didn’t have a plan and didn’t know where I was going next or how to get there. I couldn’t sleep. I had been tossing and turning for what seemed like forever when an Instagram DM popped up on my phone from a buddy, Sam. I’d served with him in Afghanistan over a decade ago. He saw I was in Costa Rica on social media and said he and a buddy of his from the Ranger Regiment were flying into San José the next day. They wanted to link up.

Game. Fucking. On.

The author on top of Cerro Negro, an active volcano in Nicaragua, about to surf 800 meters down to the base. Photo courtesy of Justin Governale.

I texted Bryan to see if he could drive me back to San José tomorrow, and for the first time since getting to Jacó, I felt a sense of simultaneous relief and excitement.

If there was anyone who could get me my adrenaline fix, it was a Cav Scout and his Ranger buddy.

The following day, I woke up to a notification from Bryan saying he would meet me at the hotel. I figured I would have time to grab coffee and breakfast, but when I got to the lobby, Bryan’s red Toyota was already sitting outside next to the curb. I ran out to tell him I needed to grab my bag and would be right out. He simply smiled wider and gave me a thumbs-up out the window.

During our drive, I got a full view of the beautiful Central American countryside for the first time. Maybe things would turn out okay on this trip? Too early to tell still.

Bryan dropped me off at a sports bar called Hooligans in San José, where I met up with Sam and his friend. I saw them before they saw me, sitting outside alone, sticking out like sore thumbs, as guys like us often do. Wasting no time, the three of us hammered a few drinks before carrying our party into a legal brothel. We were seated in a room for private parties, full of cocaine and hookers.

I didn’t have a plan and didn’t know where I was going next or how to get there. I couldn’t sleep

Ten years ago, this would have been great, I thought. I had come here to escape the everyday and trigger that flood of dopamine that only comes with the rush of adrenaline, but sitting in that brothel, I knew sex and drugs weren’t it. Still, I played along to have a good time. At one point, Sam asked me to translate for him, so he could proposition one of the women, whispering in my ear to ask her how much for the two of them to come up to his room.

Feeling slightly cynical, I leaned across the table toward the woman he was interested in and smiled.

“My friend wants to know how much it will be for him and his friend to hook up with you at the same time while your friend watches in the corner crying,” I said, amused. “She has to cry real tears, though, or nobody gets paid.”

Understandably, she didn’t know how to respond but still offered a slight chuckle.

I offered a deadpan expression. Then, slowly, her face changed as the reality of the request sank in.

She looked at Sam, furious.

Sam looked at me, confused.

“What the hell did you tell her?” he said.

Photo courtesy of Justin Governale.

I calmly told him what I had told her. Sam and his buddy laughed, and the two women realized I was joking and scolded me for saying such bad things. I simply smiled, shrugged it off, and began looking for a way back to the hotel. My work was done.

The following day, we called Bryan again to see if he could drive the three of us from San José to Tamarindo on the Pacific coast. He could, and the drive was gorgeous. We crossed countless bridges over rivers and streams through the jungles of Costa Rica. The sights and sounds of the countryside were wild and exciting. By the time we arrived in Tamarindo, I’d posted quite a few updates and had another message from someone I knew through the Brazilian jiujitsu community. As a black belt, I often teach as a guest at different schools but never expected to guest-teach at a school in Costa Rica. My friend had seen that I was heading for Tamarindo and asked if I’d be willing to stop by a local school and teach a few lessons. I immediately responded that it would be an honor and made plans to stop by the following morning.

That night, I wandered from party to party, sometimes even hopping in random cars with strangers I had just met, looking for the next adventure. I ended up at a pool party in a hotel, standing in a circle with people from all over the world. One at a time, we went around the circle, and everyone said hello in their native tongue.

One man said hello in Arabic. Teetering on half-drunk, I approached him afterward.

“Shaku maku!” I said.

The author in Tamarindo, Costa Rica, at the Tamarindo Jiu Jitsu Academy. Photo courtesy of Justin Governale.

“Where did you learn how to speak Arabic?” He looked somewhat perplexed.

I couldn’t blame him.

At first, I tried to pass it off as something I had learned along the way, but then he asked me what else I knew. Drunk and somewhat wanting his approval, I looked him dead in the eye.

“Open your door, open your hood, open your trunk,” I said in fluent Arabic.

“Line up one by one. Where is your ID? I’m going to search your vehicle. Sit down. Turn around. Shut up.” I couldn’t stop. These phrases were burned into my memory in a past life, and now, years later, they tumbled out of my mouth.

“Where are the bombs? Are you a terrorist? Okay, I am your friend, no problem.”

My new friend wasn’t impressed, and again, understandably so.

“I remember Americans coming to my house in the middle of the night and destroying our house, looking for bombs,” he replied. “My family never did anything wrong.”

These phrases were burned into my memory in a past life, and now, years later, they tumbled out of my mouth.

My mouth dried up. I tried to swallow, but I couldn’t.

“Look, I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to—”

“How many civilians died?” he asked, cutting me off. “How many soldiers? You guys came in and destabilized my country! For what? Weapons of mass destruction?”

In a matter of seconds, I had sobered up entirely but didn’t know what to say. Even if I did, he wasn’t finished.

“Imagine if someone invaded your country, kicked your door in, and destroyed your house? Your own home. How would you feel?”

The truth is, I’d have been mad, too.

“Look, man, I didn’t mean to offend you. I got a little carried away a second ago. We were all kids back then, and believe me, we thought we were doing the right thing. I lost friends, too.”

I didn’t know what else to say. What could I say? He shrugged but couldn’t let it go.

“Yes, Saddam was a dick. But he had everything under control. You guys destabilized the entire region and then just left.”

I agreed with him.

The author, right, washes laundry in Iraq using a box and bottled water. Photo courtesy of Justin Governale.

Over the years, I had concluded that the entire war was a waste and felt terrible about its negative effects on the civilian population. I genuinely liked the people over there and wished that the war had never happened.

He told me how his family had to flee when he was a child and emigrate to Canada as refugees. Over the years, I’d met several Iraqis who had fled Saddam’s regime, but never anyone who had fled after the American invasion. His perspective and completely justified emotions were something I’d never experienced, and I couldn’t help but feel guilt.

As our conversation continued, I said all of this to his face, something I’d never said to an Iraqi who had survived the war. At the end of our conversation, he stood up with a stern look.

“I’m not mad,” he said. “As long as you realize it was fucked up, we’re cool.”

He wished me good night and left with his wife. I couldn’t get the exchange out of my head for the rest of the evening. I ended up leaving the party shortly after and walking back to the hotel to get some sleep before

I had to teach the class in the morning.

The author in Iraq. Photo courtesy of Justin Governale.

That night, I had a dream about Iraq.

I was alone, standing over a man who had been shot and was dying.

“Mister, mister,” he called out while choking on his own blood.

We locked eyes, but I couldn’t respond.

“Mister, mister,” he gurgled again.

I wanted to look away but couldn’t. He coughed more blood while struggling to breathe.

“Mister, mister.”

Finally, he broke eye contact and looked skyward, struggling for shallow gasps of air before nodding slightly.

“In sha’ Allah.”

Those were his final words, a curse. With his dying breath, he told me God would avenge him.

I woke up the following day in Tamarindo. Monkeys screeched in a tree outside my hotel room window. The sounds of their calls back and forth made me feel uncomfortable. I couldn’t help but think about the conversation at the party the night before and the dream that followed.

Photo courtesy of Justin Governale.

The dream wasn’t fiction. It was something I experienced one night in 2007 after an engagement that killed two insurgents. I hadn’t expected to be thinking about that night in Costa Rica but had no doubt meeting the Iraqi refugee had sparked it. I wish I’d been more sensitive when I approached the guy, maybe tried to start a different conversation. I genuinely didn’t know many phrases in Arabic other than the hostile one-liners that had been ingrained in me years ago.

The exchange played in my mind over and over again on the drive from the hotel to the Brazilian jiujitsu academy. By the time we arrived, I felt as if I hadn’t slept at all. The humidity was so high that I could almost see it hovering in the air. As I walked to the entrance, part of me wanted to turn around, get in the car, and head back to the hotel. But I could see my contact Marco waiting at the front of the academy with a broad smile. Seeing him there, bright with anticipation, I told myself to smile and suck it up.

Be a good ambassador for the sport, I thought.

As a black belt and a Marine veteran, I couldn’t let a little humidity and lack of sleep prevent me from upholding my commitments. I shook hands with Marco, and he invited me in, where a group of students was already waiting. Inside the studio, it was muggier and hotter than outside, despite multiple noisy fans doing their best to move air around the room.

As we warmed up and started training, I began to have difficulty breathing. I’d experienced altitude sickness in Afghanistan, but this was different. When we split off into partners to grapple, breathing became more difficult. I started to feel as if I was underwater. My partner noticed me gasping for air and backed off a bit, but breathing didn’t get any easier. I began hyperventilating and quickly tapped out.

Justin Governale continues to fight in MMA while working in the BRCC marketing department. Photo courtesy of Justin Governale/Twitter.

I sat there, sweating profusely, my heart racing, trying to catch my breath to no avail. Marco approached and took a knee next to me.

“Are you okay?” he asked, putting his hand gently on my shoulder.

I nodded, telling him I was fine, even though I felt far from it. Despite taking a break, I was feeling worse almost by the second. I looked around the room. The entire class had stopped training, and it felt as if everyone was watching me gasp for air.

Marco let me catch my breath, his hand resting gently on my shoulder. As my breathing began to slow, he suggested we take a walk and get some fresh air. A gentle breeze washed over me when we got outside, and I began to feel less claustrophobic. He looked at me for a moment and smiled.

“You need coconut water, my friend! Let’s take a ride,” he said.

“Thank you,” I replied, finally able to speak again.

“De nada.”

Marco drove us to get fresh coconut water and then to the beach, where he pulled into a small parking lot with only one other car. I could hear the waves gently wash up on shore as we walked down a short path to the beach and began walking the coastline.

Photo courtesy of Justin Governale.

The air was much cooler, and the breeze and coconut water seemed to help my body feel like it was in control of itself again. The two of us walked in silence for a while, strangers until only a few hours ago. Finally, he slowed a bit and looked at me.

“I used to get panic attacks,” he said.

“Oh, that wasn’t a panic attack. I’m just not acclimated—”

“They began shortly after my baby daughter died,” he continued. “Out of nowhere, my chest would seize up, as if someone was standing on it. My heart would start racing. I couldn’t breathe. And there was nothing I could do about it.”

I silently listened as he described what I had just felt 20 minutes prior. He shrugged before continuing.

“Eventually, I figured out that drinking helped. So I did that for 20 years. It got to the point where I stopped working. Stopped living. Finally, my wife got tired of it one day and left me. I got to this point where I had nothing. No wife, no job, no house. Nothing.”

“What’d you do?”

“I faced the dragon.”

“Jiujitsu helped calm me. Taught me how to breathe, go with the flow, not fight it.”

I looked at Marco, speechless. He looked off in the distance before continuing.

“What happened with my daughter … it destroyed my heart. I became bitter. Angry for so many years. My daughter’s death became a dragon that followed me everywhere I went. I tried to drink to escape it, but I couldn’t. I had to confront it. I had to face the dragon.”

“Is that how you found jiujitsu?”

“Jiujitsu helped calm me. Taught me how to breathe, go with the flow, not fight it.”

Marco and I stood silent, watching seagulls buzz the waterline as waves gently crashed into the sand. I thought about what he had said about facing the dragon and how it connected to the conversation and my dream from the previous night.

Whether it was the humidity or a panic attack, I knew that the universe had brought the two of us together and that there was wisdom to Marco’s words.

A few days later, I said my goodbyes to Sam and his friend before jumping into a taxi with three German backpackers headed for Nicaragua. I’d heard there was an active volcano, something I’d never seen before, and traveling to see it was a promise of adventure that I couldn’t pass up.

Masaya volcano, Nicaragua. Photo courtesy of Justin Governale.

When we arrived at the border, our driver returned a little over a hundred of the dollars we had paid him and explained that he was only taking us this far, that we would have to cross into Nicaragua on foot. The money he was returning, he told me, was to pay his friend on the other side of the border to drive us the rest of the way.

The moment we crossed the border, locals swarmed us, attempting to persuade us to follow them. Over and over again, they would approach and yell “my friend!” in heavily accented Spanish before promising various things that ranged from taking us wherever we wanted to acquiring anything we wanted. Eventually, we linked up with our driver, who was surprised to learn that I was not in the same group as the Germans and demanded an extra $20 to take us to separate destinations.

We agreed and loaded our luggage onto the roof rack of his van, then stuffed ourselves inside to begin the journey to Granada. The countryside in some respects looked similar to the roads in Costa Rica, yet it had a distinctly different feel with its own sights and sounds. We often passed groups of two or three teenagers cutting random patches of tall grass with machetes. I asked the driver why, and he told me there was a shortage of grain for agricultural feed, and they were cutting grass for the livestock back at their family farms.

The road to the Germans’ destination was unpaved. It required traversing a steep gully that only a four-wheel-drive vehicle could negotiate safely. Again, to their dismay, my traveling partners were asked to deviate from their original plan. They were nearly stranded on the side of the road in a rural part of a country they weren’t familiar with, but eventually, a passing truck agreed to carry them the rest of the way.

The author’s view of Guatemala from the airplane. Photo courtesy of Justin Governale.

I thought about my plans to go farther north on the remaining leg to Granada. The days had gone by fast, and nearly a week and a half had blurred together as though I was on a bullet train of self-exploration. After mulling it over a while, I decided to flip a coin after I got to the hotel to determine whether my route to Mexico would take me through El Salvador or Guatemala.

In the hotel lobby, I found another traveler and asked her if she’d help decide for me. She hesitantly agreed, unsure of what she was signing up for. I handed her a coin I’d found at the front desk and told her to flip it. Heads I go to El Salvador, tails I head for Guatemala. She laughed but agreed and flipped the coin, catching it awkwardly.

Tails. Guatemala it was.

But first, I’d been told about Masaya, a volcano less than 20 miles from where I was staying. Masaya had an active lava lake in the center of its crater, like only a few volcanoes in the world. Luckily, I was able to book a last-minute shuttle and accompanied three women from San Marcos, Texas, on a trek to the top.

We arrived at the top of the crater just before sunset. I could see the lava lake beneath us. I could hear it, as if I were standing on the beach, listening to the ocean. I could taste sulfur, which immediately reminded me of the taste in my mouth after being hit by an IED in Iraq. I was transported to a surreal place, both in the present and the past.

I tried to drink to escape it, but I couldn’t. I had to confront it. I had to face the dragon.

Standing at the edge of the crater, the ground roaring beneath me, I became entranced by the orange glow of lava. The moment’s beauty took me back to the beach with Marco and his story about facing the dragon. This trip was supposed to be about chasing the dragon, searching for an adrenaline high that had been absent from my life for too long.

As I stared into Masaya’s fiery depths, I pondered my trip’s true purpose. The sun fell below the horizon, and dusk gave way to night, forcing my group to begin our journey back to the bottom.

The following day, I headed toward Managua to catch a flight to Guatemala to link up with a fixer in the coffee industry nicknamed “Fast Freddy.” During my 15-hour layover in Panama City, I decided to venture into the night and explore alone and without a destination. In Costa Rica or Nicaragua, it’s easy to find the action by following the sounds of music. But in Panama City, it seemed every house was blaring music, like the entire city was one giant party.

I passed countless groups of kids playing soccer, gangs of cats roaming the night, and loud dogs that reminded me I was too close to their territory. A few hours passed, and I made it back to the airport, stealing a few hours of sleep before my flight to Guatemala.

Fast Freddy pulled up to the curb at the Guatemala City airport in his white truck.

RIGHT: A gift from fixer “Fast Freddy.” Photo courtesy of Justin Governale.

I hopped in to meet exactly the sort of person you’d expect to be named Fast Freddy: He had a pistol stuffed into the bench and an ornery smile. We had been friends on social media for a while, and he had been following my trip on Instagram. When he saw I was on my way to Guatemala, he’d reached out to volunteer as a guide. After stopping at his house so I could shower, we went to Antigua, where I checked into a hostel before the two of us walked to a small bar on a narrow cobblestone road.

I asked the bartender to serve me what the universe wanted me to drink, and she returned with something she called “El Alebrije.” She told me a story about a man who created the first alebrijes, brightly colored sculptures of mythical beasts from the spiritual world he’d envisioned while having fever dreams after falling ill.

Fast Freddy had to go home, so I left the bar and found a house party where two girls offered me mushrooms. I had refused to take drugs the entire trip, but the story of el alebrije was fresh in my mind. This trip had become a spiritual journey, and I decided to allow the universe to continue taking me in the direction it wanted me to go.

Back at the hostel, I stared off into the abyss of my ceiling. I was surrounded by an orange glow and could hear the voice of Marco, telling me to face the dragon. I was standing on the edge of a lava lake, looking into the fiery depths below. Again, Marco’s voice gently told me to face the dragon. The orange glow gave way to night fog, and I could hear gurgling at my feet. I looked down and saw the Iraqi man lying on the ground, bleeding out and struggling to breathe.

The author in Nicaragua at the Masaya volcano. Photo courtesy of Justin Governale.

“Mister, mister.”

I looked down at him, trying to respond.

“Mister, mister,” he gurgled through gasps for air.

I wanted to scream. I tried to tell him to shut up, to hurry up and die. Instead, I started crying as he choked on his own blood. We locked eyes, and I couldn’t look away. Choking back tears, I finally said, nearly at a whisper, “I’m sorry. There’s nothing I can do. I wish this were different. I promise this is going to fuck me up for the rest of my life because you’re dying, and I know I can’t help you.”

His lips slowly curled upward, almost as if he were trying to smile through the labored breathing. His gaze shifted toward the sky before he whispered back, “In sha’ Allah.”

I stared at him until he was no longer breathing, finally understanding his last words. He turned to sand in front of my eyes, as did the ground around me. Now I could hear waves crashing onto the beach nearby, and I looked up to find myself back on the beach in Tamarindo that Marco had taken me to.

I was alone but could feel his presence while I reflected on the words, “Face the dragon.”

I had been traveling on a journey to chase something I didn’t need. What I needed was to trust the universe. To trust God’s will, just as the man in Iraq had done. As I stood there on the beach that slowly transformed itself back into the ceiling of my room, I forgave myself for the first time.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2022 edition of Coffee or Die’s print magazine as "Chasing the Dragon."

Read Next: A Boot Marine, a Gal Named Priscilla, and the Most Miserable Place on Earth

Justin Governale is a stand-up comic based in San Antonio, Texas. He also served as a Marine scout sniper, is a Purple Heart recipient, MMA fighter, jiujitsu black belt, entrepreneur, dog rescue/foster advocate, published writer, and former private military contractor based in Kabul.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.