‘Chosin’: The Jaw-Dropping, Must-Watch Documentary About the Legendary Korean War Battle

The name “Chosin” has a particular gravity in the minds of United States Marines. The legendary fighting spirit of the thousands of 1st Marine Division members who earned the moniker the “Frozen Chosen” during the Korean War’s Battle of the Chosin Reservoir is impressed upon every Marine in recruit training.

The battle, which took place from Nov. 27 to Dec. 13, 1950, is widely considered to be one of the Corps’ greatest triumphs, despite being one of the only instances in which Marines were forced to retreat. When the 1st Marine Division was surrounded by 10 Chinese Army divisions — roughly 120,000 Chinese — and outnumbered at least 8 to 1, Gen. Oliver P. Smith, the division commander, is said to have famously declared, “Retreat, hell! We’re not retreating; we’re just advancing in a different direction.”

Then-Col. Chesty Puller, the most decorated and arguably most beloved Marine in the service’s storied history (he earned a Navy Cross AND a Distinguished Service Cross during the Battle of Chosin), famously declared, “We’ve been looking for the enemy for several days now, we’ve finally found them. We’re surrounded. That simplifies our problem of getting to these people and killing them.”

These are the soundbites impressed upon Marines in entry-level training and passed around to romanticize the extraordinary events that took place there. But the true nature of the absolute hell the Marines, sailors, and soldiers endured at Chosin is brought into clear relief and conveyed in excruciating detail in the 2010 documentary Chosin.

Written and produced by Brian Iglesias and Anton Sattler — both Marine combat veterans of the post-9/11 era — Chosin provides a detailed oral history of the battle from the men who fought there. Their accounts are both inspiring and utterly heartbreaking.

Sattler and Iglesias, who directed the film, interviewed 186 veterans in 27 cities across 14 states for Chosin, before distilling some of the most harrowing accounts into their roughly 90-minute documentary, which won the top prize at the GI Film Festival.

The filmmakers use photos and archival footage as well as imagery from those who served at Chosin and footage from Paramount Pictures’ 1952 film Retreat, Hell! to bring the hellish battle to life for viewers.

But it’s composer Will Bates’ haunting, string-driven musical score coupled with the warriors’ unfathomable accounts of the misery they endured that makes the film a must-watch piece of history. None of the men interviewed are identified in the film, except in the end credits, a creative choice that seems intended to keep the focus on the shared misery they all endured.

“I had no boot camp. I had two summer camps. I had no idea what I was getting into,” one Marine recalls early in the film, describing how many of the Marines who fought at Chosin were barely trained reservists from the drastically downsized post-World-War-II military.

The film opens by setting the historical backdrop: North Korea invades South Korea and is on the brink of decisive victory by the time the US and other UN forces enter the war and attempt to push back the communist regime.

After Gen. Douglas MacArthur scored some strategic victories, he pressed the offensive north, intent on defeating the Korean communists and ultimately continuing into China (President Harry S. Truman famously relieved MacArthur in April 1951 for being overzealous in his intent on expanding the war to further confront the Chinese communists).

Chosin’s oral history provides a grunt’s-eye view of MacArthur’s hubris as several of the Marines and soldiers describe how MacArthur and his generals dismissed the Chinese as “laundrymen” and “volunteers” while insisting the Chinese would never enter the war.

The men who had to go up against 10 Chinese divisions at Chosin quickly learned that was not the case.

“We would capture Chinese soldiers, and they would disappear them to the rear,” says one of the men in the film, describing the days before thousands of Chinese attacked them. “Washington didn’t want them to be there, so they’re not there.”

Against this backdrop, the absolute savagery of the battle erupts around 11 p.m. Nov. 27, 1950.

Chinese flares light up the sky as whistles, bugle calls, and battle cries erupt from the ridges surrounding the American forces.

“Here came the biggest mass of men I’ve ever seen in my life, and they were armed with everything,” says one man in the film. “And I literally to this day think the earth was shaking. It was like a stampede of buffalo coming around the corner.”

“They were just coming by the thousands,” another recalls. “We wound up using our rifle butts, and cartridge belts, entrenching tools, anything you could swing at them. I had one guy bite me in the ear, and we had a struggle there. It was either kill or be killed.”

“They were just swarming. There was just so many of them coming through. We just cut loose with everything we had, and we just kept that up for hours, until it was just getting ridiculous,” another man recalls.

“Bullets were flying all over hell and high water. You could feel them hitting the ice or the snow and just flipping all over the place,” a soldier recalls. “When they jumped into my hole, the [Chinese soldier] had two grenades, and I grabbed him and pulled him in and shot him with my .45.”

The Marines fought so hard, they ran out of ammunition and then had to salvage ammo from their dead buddies and the Chinese.

In one interview, a Marine recalls the moments before his friend, Roger, dies in his arms in his foxhole. Roger asked for water, but the Marine’s water in his canteens was frozen solid, so he put snow on Roger’s lips instead.

“That was very hard on me because I had taken Roger then and used him for a sandbag around my foxhole. And I took anything I could get. Any dead Marine, any Chinamen, and used them as a perimeter around my foxhole.”

Completely surrounded by the Chinese in a valley, the Americans endured multiple similar “human wave” attacks over several days.

“You’d kill a hundred, and another hundred would come up,” a Marine recalls. “They just would make mass attacks, come right into our machine gun fire — and we were zeroed in. You know, so you didn’t have a chance when you came up there. I remember within a five-minute span, we had bodies piled 10 feet high, one on top of the other, they were using them as shields.”

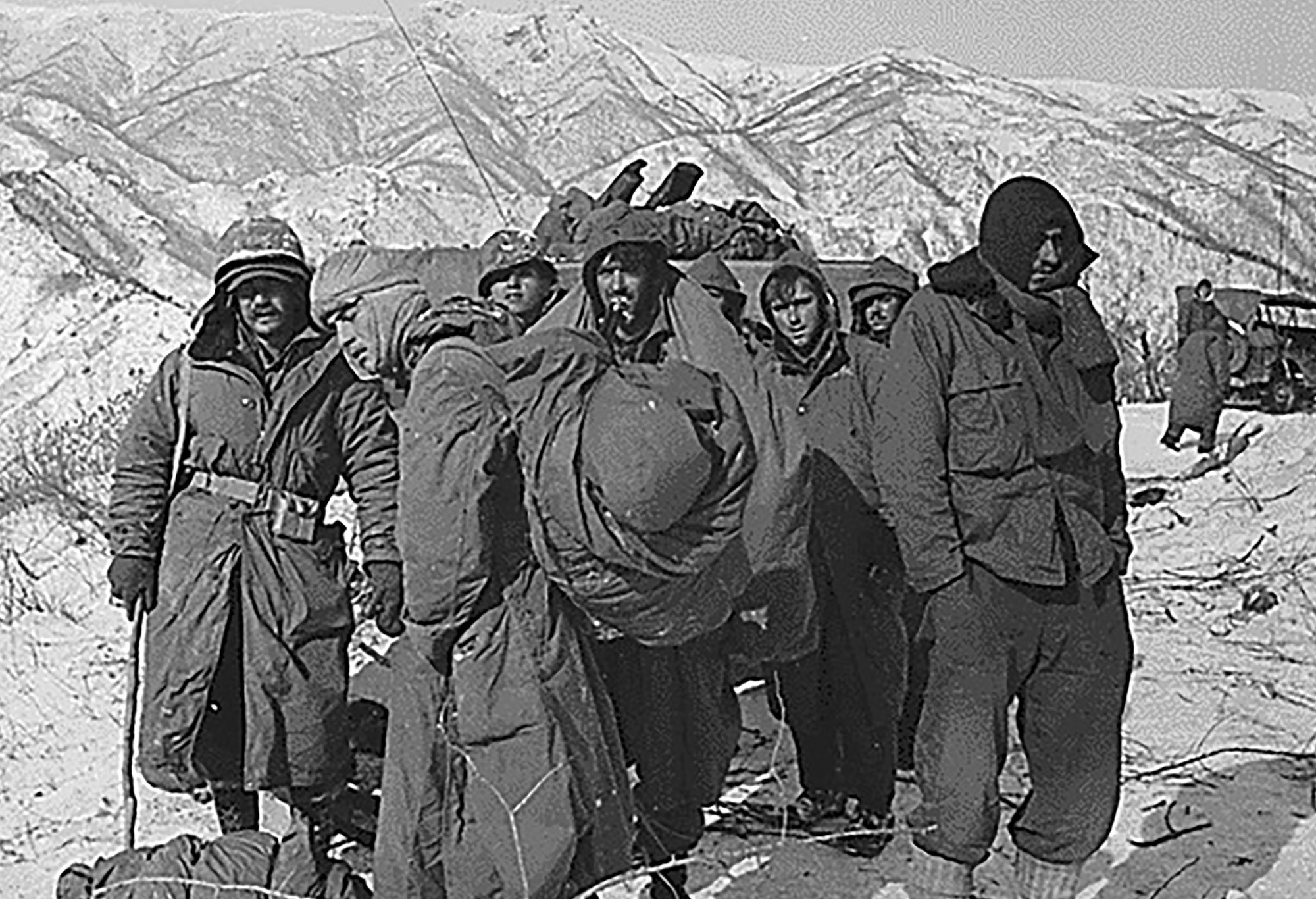

On top of the ungodly number of enemy fighters thrown at them, the Marines had to battle freezing temperatures that dropped as low as 40 below zero.

“It was so cold; our job was just to survive and do what we were told,” a Marine recalls. “It’s mind-numbing cold. You just don’t think, and you do what you have to do to survive.”

“Our eyeballs would freeze it was so cold,” says another man. “And you had to try and blink them or get some heat up with your hands to warm them up. Naturally, you never felt like you were coming back.”

By Nov. 30, the 15,000 American troops were surrounded by 120,000 Chinese soldiers, isolated, trapped, and facing total annihilation.

“You knew every time you fired your rifle, you were killing somebody, but it certainly wasn’t stopping nobody,” a Marine says describing another human wave attack.

As one Marine describes a horrific encounter with a charging enemy soldier, he talks with his hands, revealing his missing fingers, which one assumes he lost to frostbite at Chosin:

“When he came forward, I shoved my Ka-Bar straight through, and it came out the back of his neck,” he says. “When I shoved my bayonet into him, his neck just squirted blood all over me, and God, it burned my eyes, so I was getting handfuls of snow, trying to wash out my eyes.”

At one point, a Navy doctor recalls the impossible decisions he and other medical personnel had to make in triaging overwhelming numbers of casualties and choosing the dozens of troops among hundreds who could fit on evacuation aircraft. The decisions haunted him all his life.

Meanwhile, another man describes how his convoy full of wounded soldiers was ambushed and overrun by Chinese. As the Chinese comb through the trucks and piles of bodies, killing any survivors, they discover the man is still alive. Not wanting to waste bullets, they beat him mercilessly with rifle butts until they believe him dead. He recalls the events in vivid detail, all the way up to the moment when a Chinese soldier lifts his head by the hair and looks at his bloody pulp of a face as the American is careful not to breathe or move long enough to pass for dead.

By Dec. 4, Gen. Smith ordered a 78-mile fighting withdrawal from Chosin, and on Dec. 6, airplanes evacuated more than 4,300 severely wounded men, and the rest of the dead and wounded were loaded onto trucks. With barely 7,500 men left standing, the Americans began their 64-mile fight to freedom with 40,000 Chinese in their way.

When the Americans ultimately break through the Chinese lines and make it to friendly lines, they recall the brutality and carnage left:

“[Hundreds of] dead bodies of Marines were frozen stiff, often in grotesque positions, with their arms or legs extended, depending on how they’d fallen,” one Marine recalls. “You couldn’t stack them in a truck that way with their arms extended and frozen, so we would have to break their arms or legs. It was a matter of snapping them. We would snap their arms or legs so the body would be in a straight position so we could load it onto the back of a [truck].”

The sound of a low, humming wind played over archival footage of these images sent a chill through me.

As the film notes at the end, “Of the 15,000 US troops at Chosin, 3,000 were killed, and 6,000 were wounded. 12,000 suffered permanent frostbite injuries. 43,000 Chinese soldiers were killed or wounded during the battle. Two of the 10 Chinese divisions were never seen on the battlefield again. 17 Medals of Honor, 73 Navy Crosses, 23 Distinguished Service Crosses were awarded, making Chosin one of the most decorated battles in American history.”

Chosin is essential viewing for anyone wanting to truly understand why the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir stands with the Battle of Belleau Wood in World War I and the Battle of Iwo Jima in World War II as one of the Corps’ greatest moments. What those men endured during “the Forgotten War” should never be forgotten, and with this film, Iglesias and Sattler have given the American people what might be the most vital narrative ever recorded about Chosin.

You can rent Chosin on Amazon Prime for $2.99, and the film is more than worth the cost of the stream.

Ethan E. Rocke is a contributor and former senior editor for Coffee or Die Magazine, a New York Times bestselling author, and award-winning photographer and filmmaker. He is a veteran of the US Army and Marine Corps. His work has been published in Maxim Magazine, American Legion Magazine, and many others. He is co-author of The Last Punisher: A SEAL Team THREE Sniper’s True Account of the Battle of Ramadi.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.