“Holy shark, Batman!” Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

This article was written to chronicle the long-standing work by US intelligence agencies and their heroic engineering corps to keep brave pilots of spy planes safe from sharks, should their Cold War reconnaissance duties land them in shark-infested waters. Such efforts included the development of an anti-shark chemical concoction with the help of future famed chef Julia Child.

This article is not a transparent ploy during “Shark Week” to bring up the iconic Batman “Shark-Repellent Bat Spray” scene, wherein Batman and Robin use a special aerosol to defend themselves from a flying shark.

But, for good measure, here it is:

Although less dramatic than the caped crusader’s anti-shark tactics, there were a few devices the CIA equipped spy-plane pilots with to deal with nature’s hunting machines. First, pilots were issued shark repellent. Later, the CIA upgraded the agency’s flying kit to a collapsible Shark Screen.

The effort to sharkproof American spy pilots first began in 1942, in the midst of World War II. The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) — the CIA’s predecessor agency — fielded reports about curious sharks that could accidentally set off underwater explosives and potentially harm downed pilots. Those early efforts were aided by Julia Child, who’d later become famous for her humorous TV show introducing French cuisine to households across America. Child worked for the Emergency Sea Equipment (also known as the Emergency Rescue Equipment) section of the OSS. She tested more than 100 substances, including common poisons, to create a recipe not even sharks would want to eat.

“I must say we had lots of fun,” Child told OSS officer Betty McIntosh during an interview for the book Sisterhood of Spies: The Women of the OSS. “We designed rescue kits and other agent paraphernalia. I understand the shark repellent we developed is being used today for downed space equipment — strapped around it so the sharks won’t attack when it lands in the ocean.”

According to the CIA, “to create the repellent, copper acetate was mixed with black dye, which was then formed into a little disk-shaped ‘cake’ that smelled like a dead shark when released into the water,” a Washington Post article reads. “These cakes could be stored in small 3-inch boxes with metal screens that allowed the repellent to be spread either manually or automatically when submerged in water. The box could be attached to a life jacket or belt, or strapped to a person’s leg or arm, and was said to keep sharks away for 6 to 7 hours.”

Fears of sharks only intensified following the disastrous sinking of the USS Indianapolis on July 30, 1945, which resulted in several shark attack incidents. Remarkably, the shark repellent idea wasn’t abandoned after World War II. Instead, it was explored and upgraded. In 1960, during the Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union, CIA pilots flying aerial photography- and intelligence-collection missions faced real risks of being shot down over the ocean. On May 1 of that year, U-2 Dragon Lady pilot Gary Powers was knocked out of the sky at 70,000 feet by a Soviet surface-to-air missile. Although he didn’t parachute into the water, the incident proved that US spy planes were no longer untouchable.

When the public learned of the shark repellent, requests for it flooded in from the Army, Navy, and Coast Guard, all interested in equipping their troops with the new gear. In March 1944, the Naval Aviation Training Division issued a training guide based on OSS research into sharks called “Shark Sense.” Inside were fun facts and cartoons dispelling popular myths, with additional advice on how to safely survive shark-infested waters.

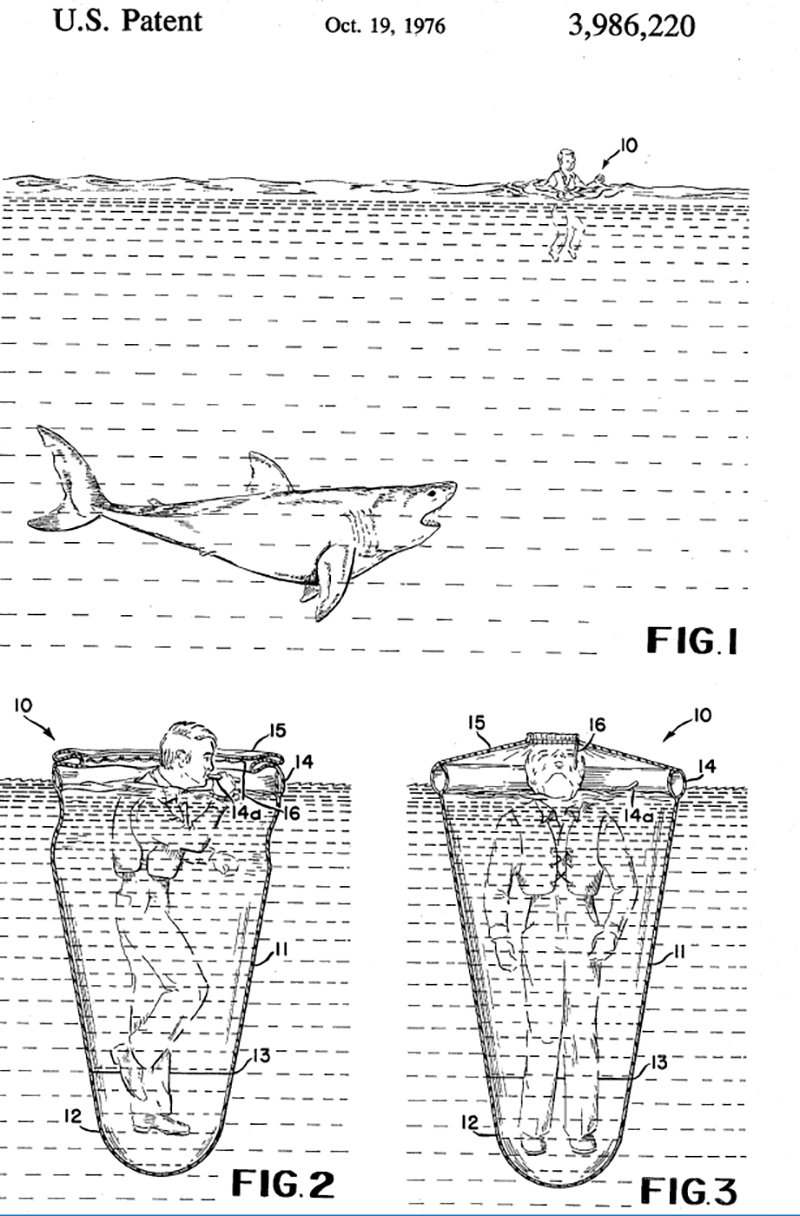

The next step for CIA engineers was an order of 50 Shark Screens. “The Shark Screen was a small, expandable, protective device that a pilot could carry and deploy in the event of a water landing,” according to the CIA. “When packed, the screen was small enough to fit into a flight suit pocket or box roughly the size of a pack of cigarettes.” Dr. Clarence Scott Johnson created the ingenious contraption in the spring of 1969.

The pilot would inflate a large tube around the opening of the bag and then climb inside with a life vest. Only the pilot’s head would be visible. While the bags were originally made of neoprene — the same material as wetsuits — aluminized mylar and polyester were deemed the perfect combination of lightweight and durable fabric. While technically a “shark bag” or flimsy shark cage, the physical barrier the Shark Screen created was also designed “to keep the blood of any wounds sustained in the crash from spreading and attracting marine life.”

In the early 1970s, the CIA’s Office of Special Activities told officers to “paint the underwater portion of your Shark Screen flat black,” adding, “It could save your life.” This begs the question: Was one of these devices used during a real operation? Although no U-2 or A-12 spy-plane pilots used a Shark Screen in the field — that we know of — the CIA made the effort to protect its pilots from sharks anyway.

Read Next: The Day a US Navy F/A-18 Hornet Shot Down One of Their Own Pilotless Aircraft

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.