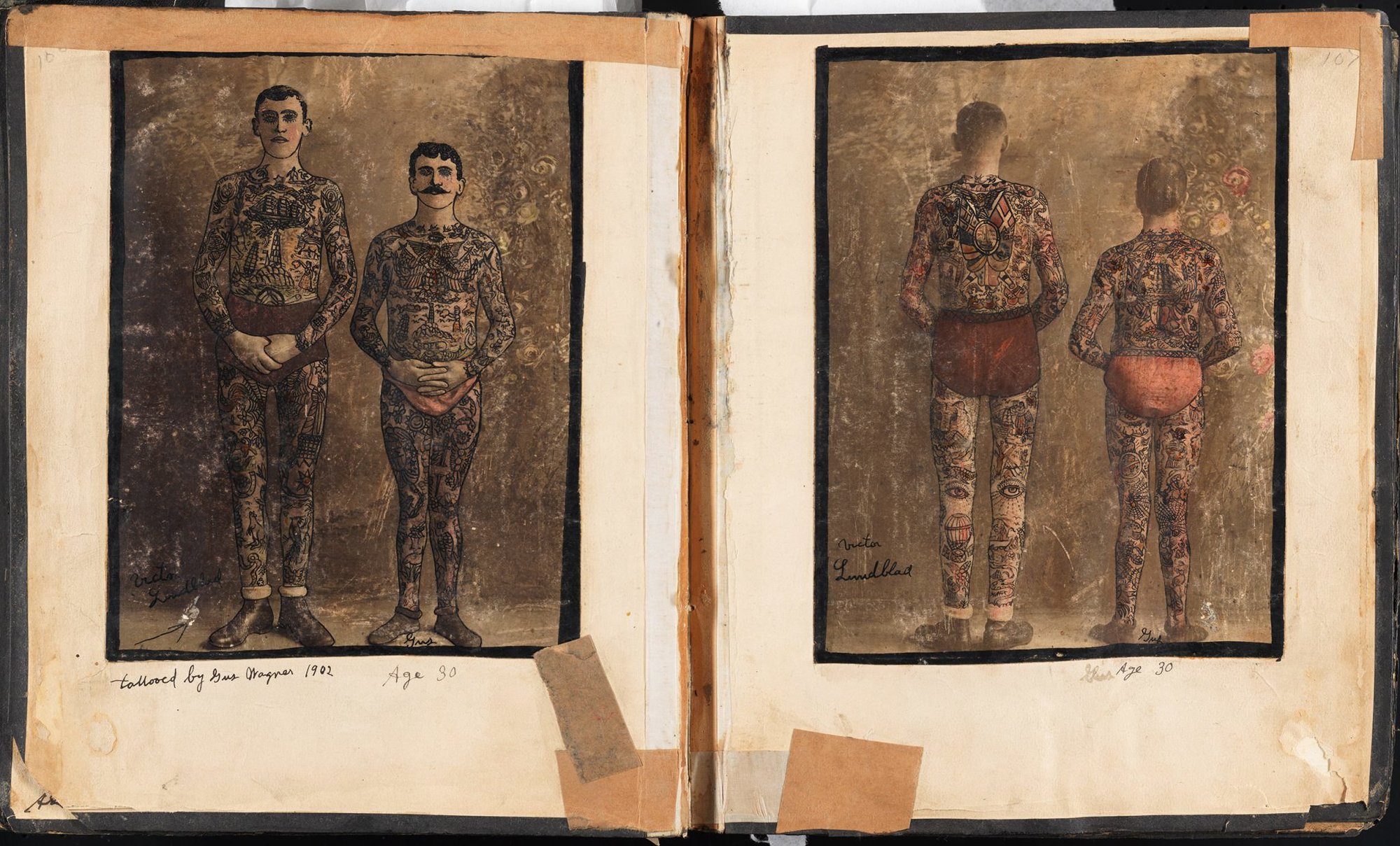

From the Seaport Museum Exhibition: page from “Souvenirs of the Travels and Experiences of the Original Gus Wagner Globe Trotter & Tattoo Artist” scrapbook, ca. 1897-1941. Photo courtesy of the South Street Seaport Museum.

In 1874, while on assignment in the Nantucket Shoals, a New York Times reporter overheard three brawny sailors in conversation, admiring the ink on each other’s arms.

“Bill, that’s the prettiest picture on your arm I ever see,” one sailor said.

Bill replied, “It’s a sailor and his own true love, and what he always leaves behind him and don’t see no more, and it was put on by the best tattoer [sic] in the United States.”

That tattooer was Martin Hildebrandt, the man whom many historians consider the first professional tattoo artist to set up shop in the United States. The German immigrant’s career began in 1846, and he went on to establish a reputation as one of the most famous tattoo artists of the era. Although his profession was largely taboo at that time — associated with Native Americans, circus performers, and sailors — some of Hildebrandt’s most frequent customers included soldiers and veterans of the American Civil War.

Still, he wasn’t the easiest person to track down.

For two years, the reporter went about his business, with no attempt to locate the tattooist, until a friend in New York City told him about a peculiar paper sign posted above a shop in lower Manhattan. The sign read: “Tattooing Done Here.”

When the reporter arrived, however, the sign had vanished. Upon further investigation, the reporter learned that policemen in the neighborhood had never seen such a sign, and the postman assigned to that route had never delivered mail to that address. Unwilling to abandon the scoop, however, the reporter looked for clues at the local sailor’s exchange. There, he was given directions to a tavern located on Oak Street, between Oliver and James — a plot of land that now sports a housing project built in the 1950s. The tavern had well-sanded floors and pictures of art and drawings hanging on the wall.

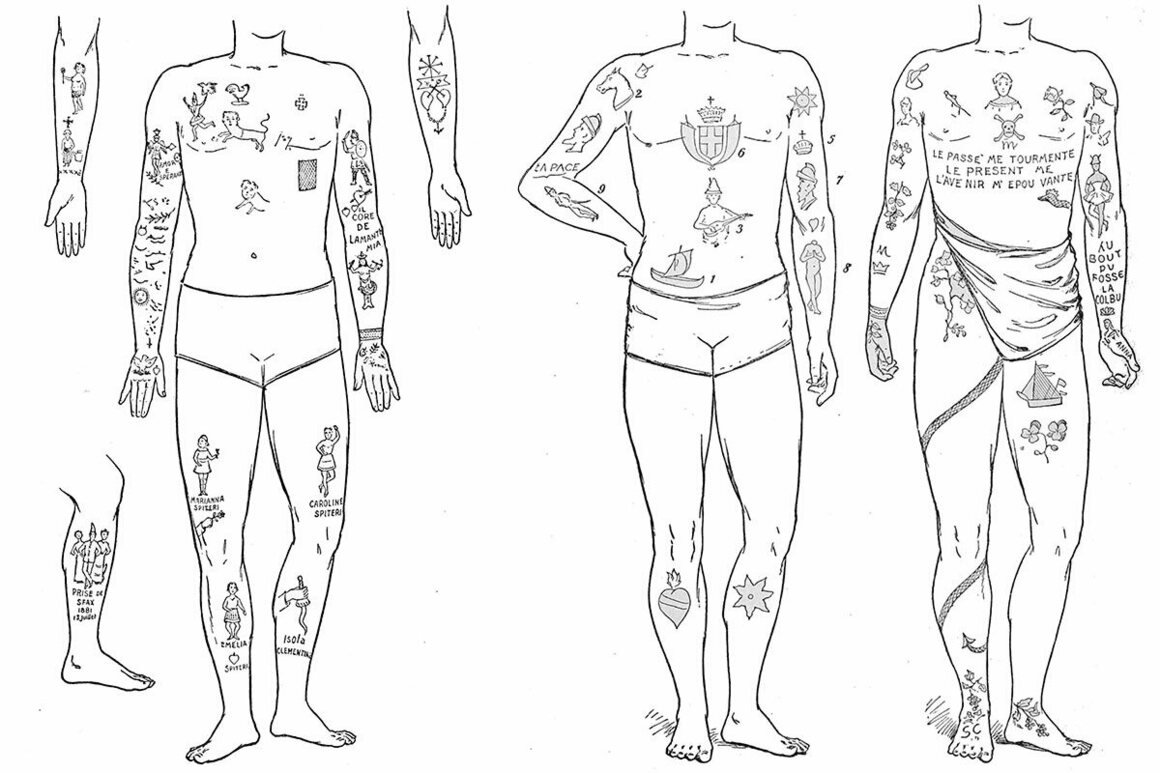

Inside, the reporter found Hildebrandt, shirtless, with a crucifix inked on his back. The tattoo artist presented the reporter with a book of art, a collection of varied designs he’d crafted over some 30 years.

“The subjects were various,” the reporter, whose name was not mentioned, wrote for The New York Times on Jan. 16, 1876. “If you were an Englishman, Frenchman, a Swede, or a Dane, there was ready for you a young lady, entwining herself in the banners of her country, ready to leave the book, and stamp herself indelibly on your person for life.”

While a design from Hildebrandt cost between 50 cents and $2.50 and could take anywhere from 15 to 90 minutes to complete, the artwork was limited.

“It is a pity we are restricted to only two colors, blue and red,” Hildebrandt said. “If we could only get a green to work into a wreath, the contrast would be charming, but I am afraid it can’t be done.”

When war interfered with his livelihood, Hildebrandt brought his unique talents to the Union Army. “During the war times I never had a moment’s idle time,” the tattoo artist told The New York Times. “I must have marked thousands of sailors and soldiers […] I put the names of hundreds of soldiers on their arms or breasts, and many were recognized by these marks after being killed or wounded.”

Hildebrandt’s tattoo method required about six No. 12 needles, bound together in a slanting form, dipped into India ink. The puncture of the skin was made at an angle, ensuring that the needles pricked only the surface.

While Hildebrandt was the only Civil War tattoo artist to speak about his profession openly, numerous works of fiction draw on historical facts, providing insights about tattooing during the time. In 1887, Wilbur Hinman, a lieutenant colonel from the 65th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, published the novel Corporal Si Klegg and His “Pard.” In the book, Hinman described the prevalence of tattoos among the Union Army’s rank and file.

“Every regiment had its tattooers, with outfits of needles and India-ink who for a consideration decorated the limbs and bodies of their comrades with flags, muskets, cannons, sabers, and an infinite variety of patriotic emblems and warlike and grotesque devices,” Hinman wrote, continuing, “Thousands of the soldiers had name, regiment, and residence ‘pricked’ into their arms or legs. It was like writing one’s own epitaph, but the custom prevented many bodies from being buried in unknown graves.”

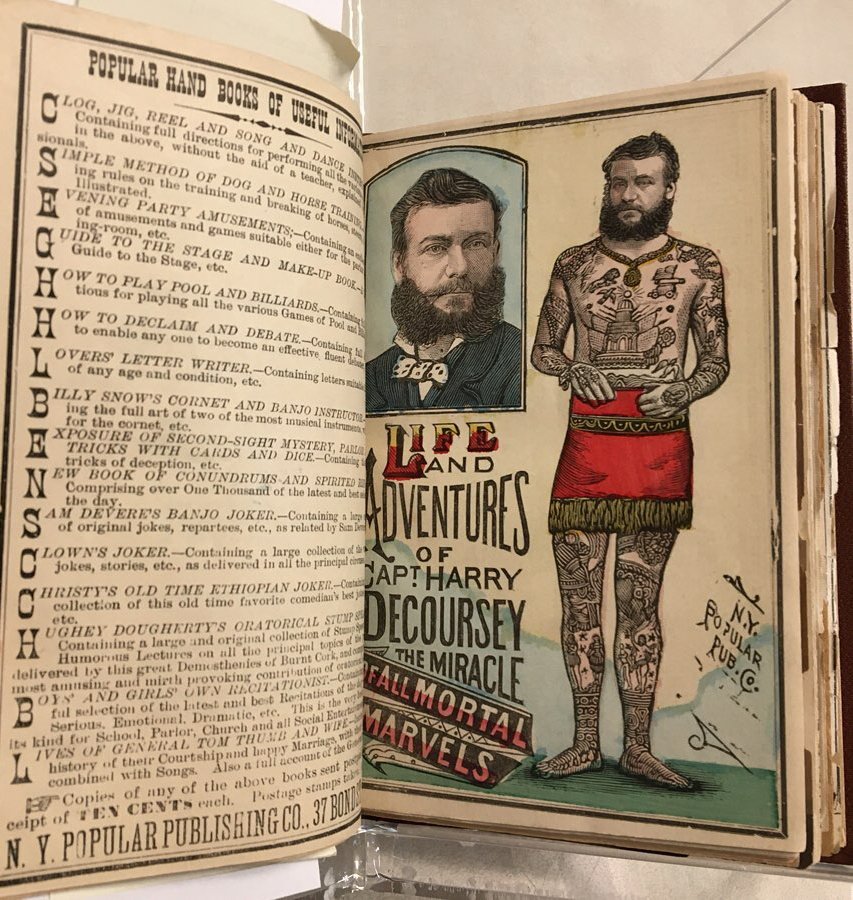

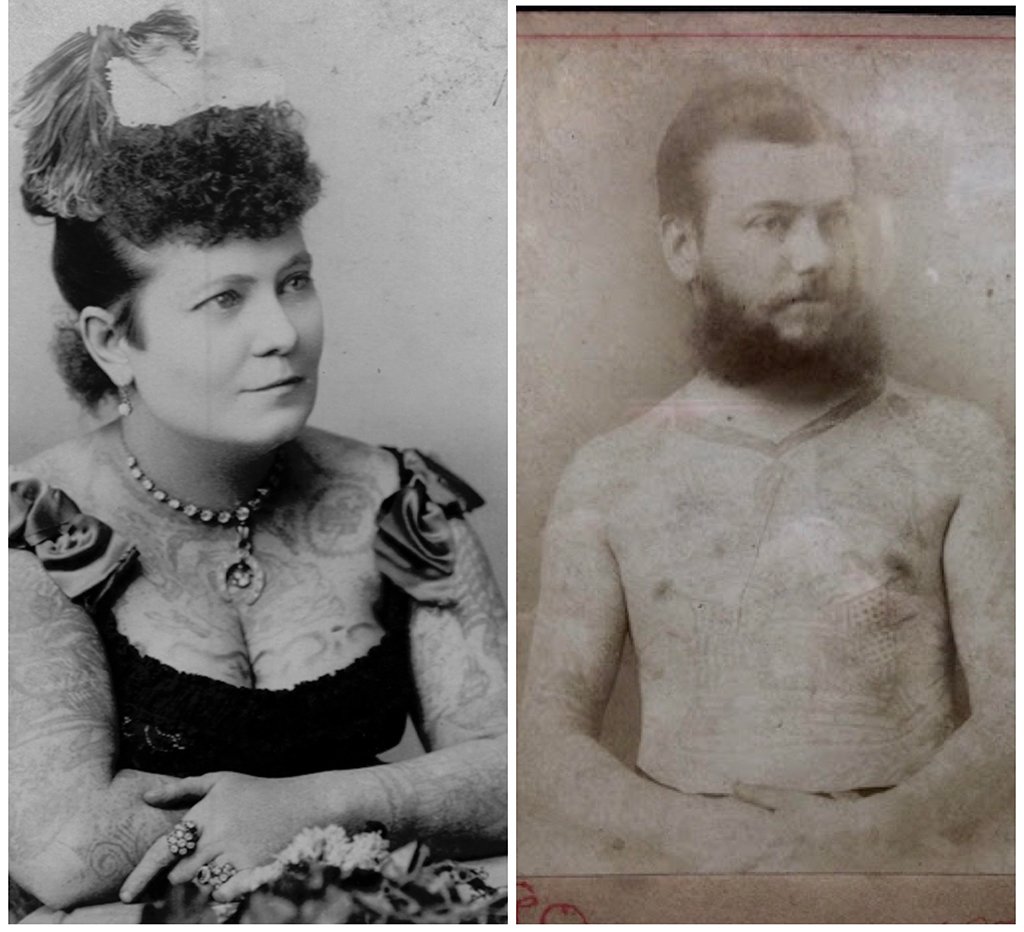

The underground tattoo industry remained prevalent after the war. A “tattooed lady” displayed Hildebrandt’s art while working as the first American tattooed circus attraction in the late 1880s. The tattooed lady’s name was Nora Hildebrandt, and some historical sources suggest she was the tattoo artist’s wife. Others, however, claim the woman adopted the name for celebrity status. Whatever the case, tattooing became a widespread practice that remains a fundamental part of US military culture in the 21st century.

Read Next:

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.