US Army soldiers Staff Sgt. Bryan Micheod, Sgt. Kyle Emery, and Pfc. Jared Specht, assigned to Charlie Company, 2nd Battalion, 502nd Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Infantry Division, detonated an anti-personnel Claymore mine at a firing range on Forward Operating Base Ramrod, Afghanistan, April 19, 2011. The soldiers practice using Claymores and other munitions to prepare for future combat operations. US Army photo by Spc. Jacob Warren.

Few weapons in the American arsenal are more easily identifiable than the M18A1 Claymore mine. Named for the legendary Scottish broadsword and packaged in a distinctive plastic case emblazoned with the words “Front Toward Enemy,” the Claymore anti-personnel mine was perfectly designed to disseminate carnage at a range of up to 50 meters.

The United States military first started fielding Claymore mines during the Vietnam War and has used them in every war it’s fought since. The US has also exported so many of the mines that they've now been used on almost every continent on Earth (Antarctica won’t be icy forever). The border between North and South Korea is rigged with Claymores, Ukraine is currently using them against the Russians, and even Central American drug cartels have started incorporating them into their arsenals.

It’s not hard to figure out why. Claymores are easy to use, highly effective, and incredibly cheap to produce, buy, and transport, weighing just 3.5 pounds apiece. Equipped to fire a wave of steel balls that fly at nearly 4,000 fps, they can be used in an ambush, as booby traps, and even to waylay moving vehicles. Furthermore, in the event that a Claymore isn’t detonated, moving it isn’t a problem. The arming process can be reversed so that the mine can be safely disarmed, carried again, and used elsewhere.

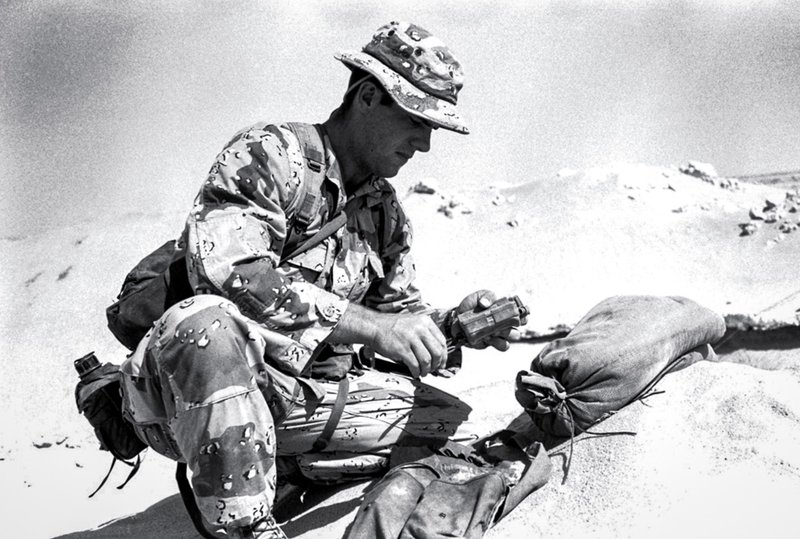

Lance Cpl. M.S. Spann sets up an M18A2 Claymore mine at the entrance to the combat operations center for the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, during Operation Desert Shield. Photo by Cpl. D. Haynes.

There are many Claymore knockoffs, but plenty of soldiers would argue that none of them is as reliable and effective as the original.

What Is a Claymore Mine?

The M18A1 isn’t buried like traditional anti-personnel mines. Claymores stand aboveground and are designed to strike their targets horizontally, rather than from below. They are kind of like a cluster of shotguns that fire all at once. As a directional mine, it throws steel balls in a pattern that spreads out from its plastic case as they hurl forward with the force of a C-4 explosion, turning anyone their path into a casualty.

Traditional anti-personnel mines are designed to wound or maim an enemy combatant, not necessarily kill them. That is not the case with the Claymore. In fact, it was conceived as a weapon capable of inflicting enough carnage to halt an enemy advance or, at least, cause enough casualties to create a logistical nightmare. Which is to say, M18A1 Claymores aren’t just intended to wound. Anyone who survives a Claymore is either extremely lucky or was just too far away from the mine when it exploded.

Senior Master Sgt. Jason Knepper, Air Force Reserve Command security forces training manager, demonstrates how to rig a claymore on March 17, 2023, at Camp James A. Garfield Joint Military Training Center, Ohio. Knepper demonstrated claymore defense tactics to Integrated Defense Leadership Course students to develop combat readiness skills necessary for wartime situations. US Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Christina Russo.

The Claymore is fielded with everything one might need to rig the mine for any of its intended uses. The M7 “Claymore bag” is a bandolier that includes the M57 firing device (also known as a “clacker” for the sound it makes), an electric blasting cap, and wire. The specially made carrying case and its overall compact size made the M181A1 easy for American GIs in Vietnam to use to defend against ambushes and to carry out their own.

The Claymore’s green, slightly convex plastic case is stamped “Front Toward Enemy” on one side and “Back” on the other side. The letters are raised to ensure that even in the dark a brand-new grunt will at least know which direction the mine should face.

How a Claymore Mine Works

For better or worse, rigging a Claymore is easy enough that almost anyone could do it — and not just because the mine tells you which way it should point. Inside every M7 bandolier bag is a set of instructions on how to arm the mine. Troops using these mines rig them in a controlled blast — using the clacker as a booby trap, a tripwire firing system, or a daisy chain for a greater area of destruction.

A US Marine with the Basic School holds an M18 Claymore mine in preparation of live-fire demonstrations for the Murphy family at the Murphy Demolition Range, Marine Corps Base Quantico, Virginia, April 30, 2015. The Range was named after Maj. Walter M. Murphy for his bravery during the Vietnam War at Hue City. US Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Emerson P. St John.

Once a location is chosen, the mine can either stand on its own or make use of four, 6-inch scissor-style legs that can be planted into soft ground. The top of the Claymore has a simple peep sight, used to aim the blast at a semi-circular field of view.

Inside the M18A1’s plastic case are 700 steel balls, 1/8th of an inch in diameter. The balls are embedded in a pound and a half of C-4 explosive and sealed in epoxy resin. When the weapon is triggered, they are launched in a fan-shaped pattern along a 60-degree arc, forming a wave of steel 2 meters high and 50 meters wide. Although 50 meters is technically the Claymore’s effective range, it is still capable of wounding or killing targets at twice that distance.

The blast of a Claymore is highly concentrated in one direction, but that doesn’t mean it can be held and fired like a gun. Since backblast is highly likely, soldiers operating a Claymore are advised to take cover at least 20 meters behind the mine, such as in a foxhole. Because, of course, the only thing worse than getting shredded by an enemy booby trap is getting shredded by your own.

History of the Claymore Mine

A US Marine with Alpha Company, Infantry Training Battalion, School of Infantry-West, places an M18 Claymore mine during a practical application session as part of the 11th week of the Infantry Marine Course on Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, California, April 5, 2021. US Marine Corps photo by Sgt. Jeremy Laboy.

During World War II, Axis weapons manufacturers sought to develop an anti-tank mine that could penetrate the sides of Allied tanks. As one result of that effort, Hungarian scientist József Misznay and German scientist Hubert Schardin discovered how to direct sheets of explosives using a rigid backing. Their work was picked up later, during the Korean War, when the Chinese began using human wave attacks to overrun United Nations troops.

Conventional landmines were too bulky and impractical for the kind of infantry combat that kept units moving from hilltop to hilltop within days or even hours. During the Korean War, the Canadians developed the Phoenix landmine, which used the Misznay–Schardin Effect (and five pounds of Composition B explosive) to directionally launch steel cubes. The problem with the Phoenix was that it was too large and too heavy for infantrymen to carry in the field. Its effective range was also unimpressive.

In 1952, while the Korean War was still ongoing, English inventor Norman MacLeod built upon Misznay and Schardin’s research to develop a directional mine for use by the US military. His device, called the T-48, was essentially a rough draft of the Claymore mine. This first version was heavily flawed, but over time, it was engineered to perfection. The US bought 10,000 of them and began sending them to South Vietnam in 1960.

During a training exercise, Airman 1st Class Howard, 822nd Security Forces Squadron, Moody Air Force Base, Georgia, checks his M18A1 Claymore mine to see if it’s properly aligned at Camp Blanding, Florida. Photo by Senior Airman Felicia R. Newton.

During the Vietnam War, US troops used Claymore mines to help defend the perimeter of their bases from human wave assaults and infiltration by sappers — tactics the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong both used to overrun American positions. South Vietnamese and American troops also carried Claymores into the bush for staging ambushes — something the mine was well-suited for as it had a greater effective range than grenades.

Are Claymore Mines Legal?

Claymore mines are legal for use by US military personnel. This is because the US is not a signatory to the 1997 Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production, and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction, better known as the Ottawa Treaty.

The Ottawa Treaty prohibits “victim-activated” weapons — i.e. mines that are detonated by proximity to, or contact with, a person. The most recent American policy regarding the use of landmines was updated in 2022. Although the US didn’t sign on to the Ottawa Treaty, the Biden Administration’s policy does align “with key provisions of the Ottawa Convention for all activities outside the context of the Korean Peninsula.”

Marines with 3rd Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment, were given instructions on how to properly place an M18 Claymore during lane training at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, Oct. 20, 2015. Placing claymores was one of four stations the Marines visited during the training. The other stations covered patrolling, communications, and grenade handling. US Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Preston McDonald.

The policy states: “the United States will not develop, produce, or acquire anti-personnel landmines, not export or transfer anti-personnel landmines except when necessary for activities related to mine destruction or removal and for the purpose of destruction.” That being said, the US considers Claymore mines to be “Ottawa compliant” because they can be command-detonated (triggered by an individual using the clacker). This, in theory, reduces the potential for “collateral damage,” as the Claymore operator can identify his target, ensuring it’s an enemy combatant, and not a civilian, before detonating the mine.

Claymore Mines in Use Today

It’s hard to justify phasing out a weapon as versatile, effective, and portable as the M18A1 Claymore. After the Vietnam War, the United States continued using Claymore mines during the Cold War, in the Gulf War, the Balkans, and on into Global War on Terror. Right now, as you read this, there’s a grunt-in-training somewhere learning to use an M18A1 peep sight.

The Claymore is such a perfect infantry weapon that militaries around the world developed off-brand copies for themselves. Some of those militaries belong to America’s current geopolitical rivals, including Russia. Some are former adversaries, like Vietnam. Others, like Pakistan, China, and Chile, just know a good thing when they see one.

Read Next: The M14: America’s Last Battle Rifle

Randall Stevens is a military veteran with more degrees than he knows what to do with. He enjoys writing and traveling, and has an unnatural obsession with Harry Houdini.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.