Coast Guard Maritime Safety and Security Team Los Angeles-Long Beach crewmembers conduct a tactical demonstration in the Port of Los Angeles, March 21, 2019. The demonstration followed the 2019 State of the Coast Guard Address delivered by Adm. Karl Schultz, Coast Guard commandant. (U.S. Coast Guard photo by Seaman Ryan Estrada /Released)

Before the U.S. Coast Guard was hunting down narco-drug traffickers in submersible submarines and using advanced Search And Rescue (SAR) technology like high-frequency coastal radar and Sikorsky helicopters, the early heroes of the U.S. Life-Saving Service (USLSS) had to do it the old-school way.

When rough seas and vicious winds tore apart vessels and transformed them into relics of the sea off the coast of Massachusetts — then later from Maine to Florida, the Pacific West Coast, Texas, and the Great Lakes — the survivors found themselves stranded ashore with little hope for survival. An urgent humanitarian crisis developed, and as people continued to die, life-savers were thrust into action to prevent loss of life.

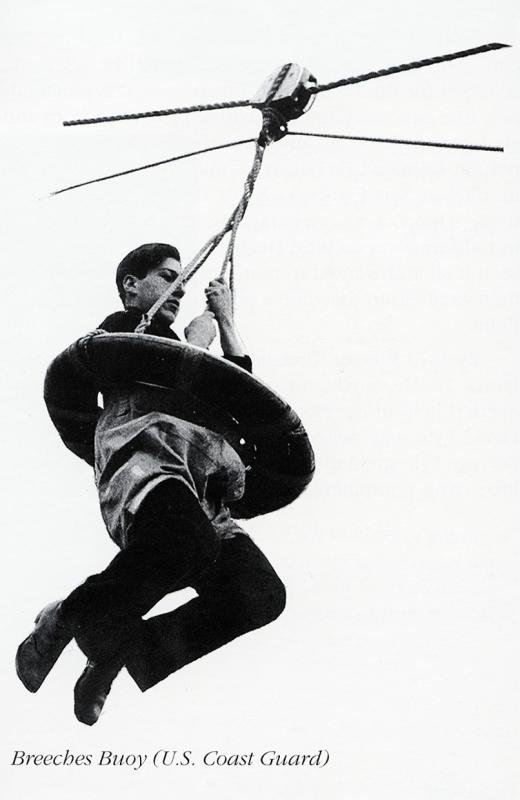

The early beginnings of the USLSS were fraught with maritime heroism and ingenious transformations of which all Americans should be proud. From the surfmen and keepers that patrolled the shoreline to the creation of signal flares, zip-line buoy systems, and line-throwing rockets — these tools and methods provided the necessary means to extract victims from the grasp of Mother Nature.

From the Ground Up

Highbrow figures in Boston met at an 18th-century tavern called Bunch of Grapes to discuss the prospect of forming a government-funded outfit to respond to dire coastal emergencies. Modeled after China’s Chinkiang Association for the Saving of Life — the earliest organization of its kind — and drawing from the lessons from the British Royal Humane Society, the foundation for what would become the U.S. Coast Guard was laid.

The Massachusetts Humane Society (MHS) erected the first set of small huts spanning from Scituate Beach to the islands of Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard. From 1787 to 1806, 18 huts were established to provide shelter for those who survived a shipwreck and scraped out of the ocean alive but fatigued. In these huts were a tinderbox for fire to provide warmth, matches with candles for light, and provisions to regain strength. Years later, the same principles used to establish these houses of refuge, as they were affectionately called, was put into place along the Florida panhandle using farmhouse architecture.

Similar to the military and warfare, when there is a prompt need for a new organization dealing with matters of life and death, the innovation of TTPs (tactics, techniques, and procedures) and theoreticized equipment are expedited. The “houses of refuge” were a minor fix to a complex problem that spread across the country. Sailors were still dying, and in 1807, a Nantucket designer named William Raymond was tasked to build a lifeboat.

According to the authors of “The US Life-Saving Service: Heroes, Rescues, and Architecture of the Early Coast Guard,” “The first American lifeboat was a 30-foot long whaleboat rowed by ten men and guided by steering oars.” The MHS was responsible for pioneering the British-born premise into a lifeboat of their own and installed the first lifeboat station, which helmed in Cohasset, Massachusetts, a tiny seaside town located approximately 27 miles southeast of Boston.

As the effectiveness of the Humane Society grew across Massachusetts, word spread to New Jersey, where Congressman William A. Newell passed a law on Aug. 14, 1848, that called for $10,000 in life-saving equipment. The funds provided wooden boathouses from Sandy Hook to the Jersey Shore. They were small in size and inside had lanterns and minor equipment that could be used to fix and reinforce the tools to their trade. Outside, these tiny houses had a metal surfboat, a mortar, rockets, and a lifecar.

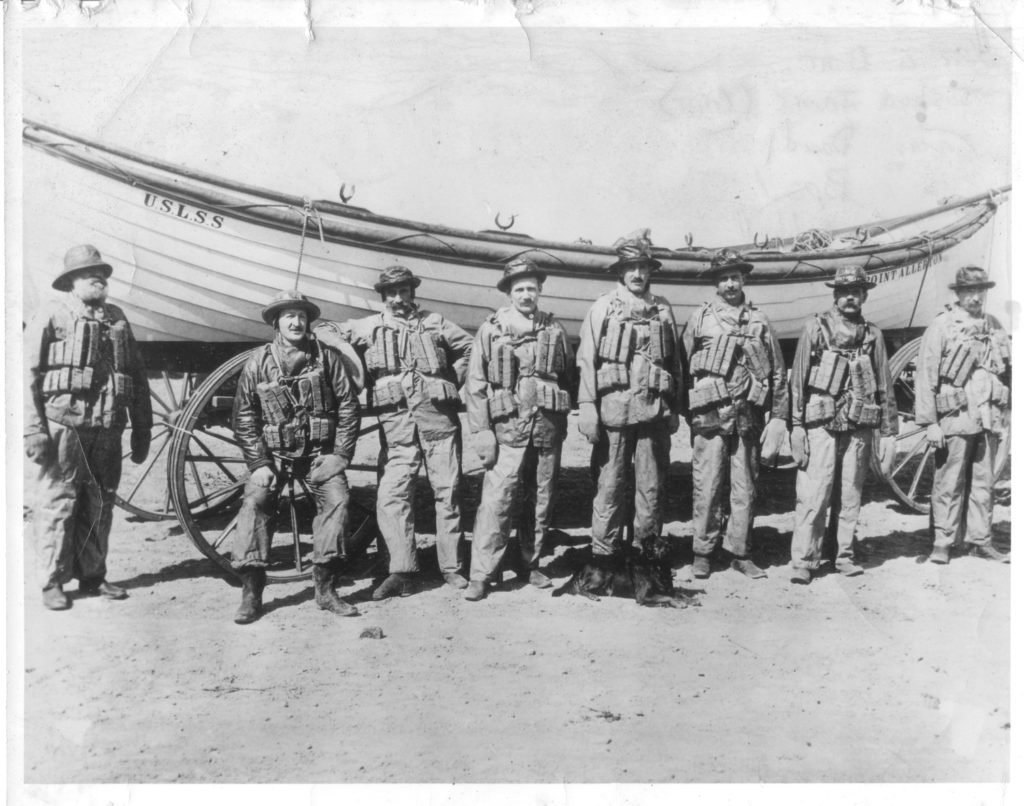

These boat houses were later molded into much larger two-story life-saving stations; some were even equipped with lookout towers. Over time, these life-saving stations were the home of surfmen and keepers, who worked and launched rescue operations out of them. The USLSS also had two mobile floating bases in its arsenal.

The first was the Louisville Life-Saving Station at the Falls of the Ohio in Kentucky. It looked like an ordinary house with an attachable garage, except the opening was only accessible to seaborne crafts rather than vehicles with tires. The second was called the City Point Life-Saving Station, which helped rescue casualties in Boston’s Dorchester Bay. When viewed from afar, it had a ship-like appearance rather than a settled staging area.

As more accidents unfolded off the various coasts around the country, the public outcry became too much. The official establishment and expansion into the USLSS was signed into law on June 18, 1878.

Surfmen & Keepers

The men that filled the ranks of the USLSS were called surfmen and keepers. They were highly skilled, expertly trained, and had the wherewithal to solve dynamic problems on the fly as relentless breakers punished them in rounds. Their motto read: “They had to go out, but they did not have to come in.” Surfmen were held in the highest esteem and applauded by the Wright Brothers and artist Winslow Homer, who depicted them in a painting titled “The Life-Line” showing the rescue of an unconscious woman using the breeches buoy.

Their motto read: “They had to go out, but they did not have to come in.”

Surfmen were of all races and creeds and, despite the tumultuous relationships influenced by politics, all bonded over the purpose of SAR work. Native American Indian tribes — from the Gay Head Wampanoag in Massachusetts, the Shinnecock in Long Island, the Makaw and Quileute on the Pacific Coast and Great Lakes, and the Chelhalis and Quinault in Texas — contributed to early life-saving operations. Asian-Americans, including Japanese-born F. Miguchi, proved capable as well. Miguchi was awarded the Congressional silver life-saving medal for helping a drowning sailor.

While serving on the U.S. Revenue Cutter Gresham, Miguchi dove overboard when one of his shipmates waded farther that his feet could touch and started to drown. Other members of the crew tried to locate him, but he had submerged underwater and was lost. Miguchi dove overboard, swam to his last known location, took a deep breath, and plunged head-first into the water to find his shipmate. He only returned for air when he had secured the victim, practicing the technique of swimming underneath the victim to keep his head above the water.

Black surfmen served through the most treacherous of deep seas, including the infamous stretch on the Outer Banks of North Carolina dubbed “The Graveyard of the Atlantic.” In “The US Life-Saving Service,” the authors note how the district superintendent of the USLSS chose Richard Eldridge in the 1890s and spoke of him having “the reputation of being as good a surfman as there is on the coast, black or white.”

Almost all men were either clean shaven or had thick-bristled mustaches. At first they were responsible for clothing themselves, but then they were issued uniforms, which they purchased on their own. Surfmen had two sets: one for formal photoshoots and the other for work.

The formal attire looked similar to the keepers’ uniforms: a dark-blue turtleneck sweater with a well-fitting cap that mirrored one worn by a train conductor. Inscribed across the cap were the words, “US Life-Saving Service.” The work dress included an all-white coat and pants, with a rounded-style cap similar to a bucket hat. When tasked with a rescue, they threw on their brown rubber storm suits; if things got dicey, they added life jackets and hip boots.

The keepers were hand-picked from a pool of the most outstanding surfmen. In order to lead a successful rescue mission, keepers had to perform with extraordinary courage, needed to possess the mindset for an unorthodox approach to planning, and required maturity to handle post-traumatic events by providing support for the survivors. Keeper Joshua James, a Hull native, is considered the most famous life-saver in U.S. history.

Across his 60 years of service, beginning at age 15, he was responsible for saving more than 1,000 lives.

His legend grew and many claimed he could “hear the land speak.” After a violent squall capsized a sailing vessel and killed his mother and sister when he was only a boy, James vowed to not let others experience the grief he had felt nor the helpless terror his mother and sister experienced. Across his 60 years of service, beginning at age 15, he was responsible for saving more than 1,000 lives. He also played a major role during the Great Blizzard of 1888 that made life at sea a nightmare for mariners. James led his crew through monstrous overhead waves to help submerged and frantic victims.

The storm produced wind gusts of over 80 mph, below-freezing temperatures, slicing sleet, and blankets of snow that harassed anyone it touched. Many things changed afterward, including the shift in putting power and telegraph lines underground because of the storm’s mayhem.

In two late November days, James led the MHS in rescuing 29 men from six different shipwrecks, despite being 62 years old. James never let his age hinder him, and he spent a lifetime honing his skills and mentoring younger surfmen until his death. At 75 years old, James collapsed stepping off a boat onto shore. Those who were alongside him said his last words were, “The tide is ebbing.”

Tools of the Trade

Surfmen used mortars, lifecars, and buoys attached to zip-lines. Their oar-rowing, 34-foot surfboats grew 2 feet in length and adopted motors upon entering the 20th century. Surfmen grew exhausted working round-the-clock routines up and down the beach, and most were in spectacular physical condition. Those with families had entertainment through dances and songs in the life-saving stations, while others who were more secluded passed the time by strumming banjos and guitars. Some surfmen had side hustles to supplement their income, working off the land as fishermen, loggers, farmers, and whalers.

Life-saving was a noble but dangerous career and attracted public intrigue. The famed Apache chief Geronimo admired their work and marveled during the breeches buoy demonstrations and capsizing drills that they conducted throughout the week. During such presentations, keeper Henry Cleary of Marquette, Mich., Life-Saving Station showed off his speed. His fastest capsize drill time was 13 seconds, a record amongst surfmen and keepers. When the surfmen weren’t rowing until muscle failure to save mariners terrorized by the stormy ocean, they used their “off” days to practice. Their basic tools included the heaving stick & line and portable off-shore line-throwing devices.

The heaving stick & line was as basic as it sounds — the rescuers would hurl an oval weight to the injured person to grab and hold on to while they were hauled to safety. The portable off-shore line-throwing tools were pioneered by Englishmen George William Manby, who also invented the first portable fire extinguisher. In 1807, he had witnessed a boat perish from the shores of Yarmouth, just 60 yards from his location. As a teenager, he made a homemade mortar that launched a line through the air, over his church, and, much to his shocked and appalled mother’s eyes, right through a nearby window.

Manby improved his concept, and his rocket apparatus became the cornerstone of American rescues between 1849 and 1871. These evolved into the use of the Hunt Gun, created by Weymouth, Massachusetts, native Edward S. Hunt. Then, ultimately, the Lyle Gun, a 185-pound bronze cannon pushed along the beach on two wooden wheels with an approximate range of 700 yards. They fired projectiles rather than floating preservers. The rockets would fire within reach of the shipwreck, and the survivors would pull the line aboard. Attached was a “tally board” with instructions written in English and French. These boards broke up the confusion for both the surfmen and the casualties.

Lifecars were used to pull victims from boats to the shore on an attachable pulley system. They were similar to submersible submarines with two to four victims entering from the ship and shutting the hatch behind them. Rescuers would then pull them to shore as they bounced through the waves. “The most successful method of bringing survivors ashore by lines was the breeches buoy. A breeches buoy consists of a common cork-filled life ring (a circular life preserver) with a pair of short-legged oversized canvas pants sewn inside. The person got into the breeches buoy as if putting on a pair of pants,” noted the authors of “The US Life-Saving Service.”

Paul Boyton, known as the Fearless Frogman to his fans, accumulated over 25,000 miles in the rubber life-saving dress. From the water, the full-bodied suits closely resembled a creature from the Black Lagoon, until Boyton made the public aware of his presence. He assisted the USLSS and later perform in his very own “Paul Boyton’s Water Circus,” where one of his acts involved using floating water boots to walk across water.

After his untimely death, innovation prodigy Benjamin Franklin Coston’s widow, Martha Coston, reinvented her husband’s desire for using the signal flare in life-saving measures. The Coston flare was used to warn ships from the shore or to communicate amongst vessels while in rough seas. Martha Coston paved the most significant role for women in the USLSS.

The USLSS merged into the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service in 1915 and ratified its current name: the U.S. Coast Guard. The Coasties have a long and glorious family lineage that USLSS helped form when it mattered most.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.