Coast Guard in 1920: Bootleggers beware!

A Coast Guard aircraft and crew standby, ready to spot smugglers during Prohibition. Photo courtesy of Coast Guard Atlantic Area Historians Office via the Department of Defense.

This article was originally published on Jan. 17, 2020, by the Department of Defense.

On June 21, 2019, the Coast Guard and the U.S. Customs and Border Protection unveiled a remarkable feat – the interdiction of more than 16 tons of cocaine, worth approximately $1 billion. The haul was described as “one of the largest drug seizures in United States history” by U.S. Attorney William M. McSwain. Less than 100 miles away and more than 100 years ago, a similarly historic interdiction had taken place.

William “Bill” McCoy infamous smuggler of alcohol during Prohibition had been caught and arrested by the crew of Coast Guard Cutter Seneca six miles off the coast of Seabright, N.J., in 1923. The interdiction occurred after a long, tense standoff, which ended when a round from the Seneca’s deck gun landed mere feet from the fleeing ship. The arrest essentially ended McCoy’s storied career as a bootlegger, and foreshadowed the Coast Guard’s present-day maritime law enforcement mission.

Prohibition began on Jan. 21, 1920, under President Herbert Hoover’s administration. To enforce the new laws, a Prohibition Bureau was established and was almost immediately overwhelmed. Despite having a marine division, alcohol smuggling was too lucrative, and therefore too prevalent. The Coast Guard became the go-to resource for enforcement, but there were issues with this solution.

“The major issue for the Coast Guard at the time was insufficient funds and resources,” said retired Coast Guard Capt. Daniel Laliberte, former Intelligence Chief for the Fifth Coast Guard District. “The Coast Guard was fully funded for the missions it had at the time, but the major issue was that it wasn’t funded to run an entire coastal interdiction program.”

Laliberte has studied the Coast Guard’s role during Prohibition and is currently writing a book on the subject.

“Other issues were limits on its enforcement authority. At the time, they only enforced U.S. law out to three nautical miles. Another big issue was the need for training and experience. The Coast Guard had no training, tactics and procedures for criminal law enforcement,” said Laliberte. “We didn’t have a law enforcement manual until the 1930s.”

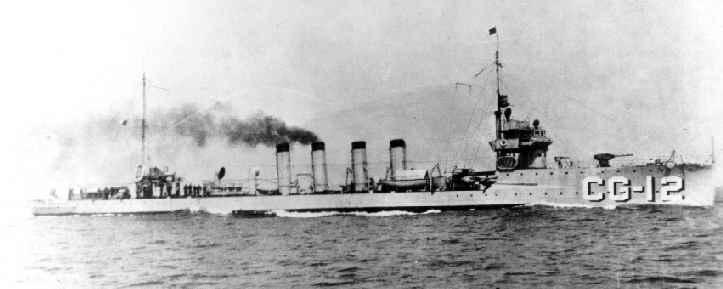

Seeing the demands being placed upon his service and measuring current capabilities, Coast Guard Commandant William Reynolds worked with U.S. Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon on a Congressional proposal for additional funds in 1921. The result ballooned the service’s ranks from 4,000 to 10,000 and a fleet of vessels capable of carrying out the new law enforcement expectations to include 20 refurbished Navy destroyers.

“It was a tremendous expansion and increase in capability,” said Laliberte. “They basically had to continue all the missions they were funded for and needed a new funding string for Prohibition. It was a huge amount of money, but it really allowed them to build a defense in depth.”

In addition to the increased presence on the water, the Coast Guard also applied some of these new funds to provide a presence in the sky.

“Aviation was another interesting thing,” said Laliberte. “It initially started off small, but it ended up with five planes and they were mostly used as recon to go out and find where the ships were on Rum Row, monitor them and report back. Much as they do today in drug interdiction. There were even cases where from the air, the aircraft shot up cases of alcohol that had been jettisoned.”

Rum Row was a term used to indicate where “mother ships” would position themselves awaiting offload of contraband. Initially, these larger ships would anchor three miles offshore, where it was believed that no law enforcement agency had jurisdiction. However, with new and more lenient legal interpretations of the Coast Guard’s authority and a new fleet of cutters and boats on the water, smugglers learned quickly the extent of the service’s commitment.

“In two years, they’d basically dispersed Rum Row,” said Laliberte, “but the smugglers responded by moving Rum Row further and further offshore.”

As the Coast Guard escalated their response, the smugglers began to take a more strategic approach. More boats and crews weren’t enough. The service needed intelligence.

“The Coast Guard had no formal intelligence apparatus, but it started one at headquarters,” said Laliberte. “They worked hand in hand with the Prohibition Bureau and the State Department. The intel program put out lookout lists, they worked off of tips from the public and passed information to the stations and cutters. It was kind of an integrated thing, on a shoestring.”

That shoestring paid for the Coast Guard’s first codebreakers and an international connection of informants working out of Cuba, the Bahamas and other neighboring countries, helping the Coast Guard stay one step ahead of their quarry.

On Dec. 5, 1933, Prohibition was repealed, bringing an end to more than a decade of intensive law enforcement action, which saw Coast Guard members shedding blood and even losing their lives in the line of duty. Without a constant threat to address with their fleet and increased numbers, the service saw the pendulum begin to swing the other way.

“Within a year after Prohibition ended, the budget was cut by 25% and drew down,” said Laliberte. “And then you had World War II a few years later and the Coast Guard was very active during that.”

During the 13 years that Prohibition was in effect, the Coast Guard underwent a transformation in capability, in mission and culture. Similarly, today’s Coast Guard is vastly different than it was 100 years ago. The modern iteration of the service includes many more elements of law enforcement and defense readiness, and provides its members with the training and procedures necessary to facilitate operational excellence. The Coast Guard of 2020 averages 1,221 pounds of cocaine interdicted, 48 waterborne patrols, 12 security boardings and screens 329 merchant vessels daily. Aviation is as much a familiar aspect of the Coast Guard’s identity as any cutter or small boat and the ranks of our service have swelled to more than 38,000 active duty. Despite the many innovations and transitions, the one clear holdover from 100 years ago is a commitment to service and a dedication to duty.

For more content like this, visit https://www.dvidshub.net/news.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.