How an FBI Program of Surveillance and Harassment Broke Up a Civil Rights Group

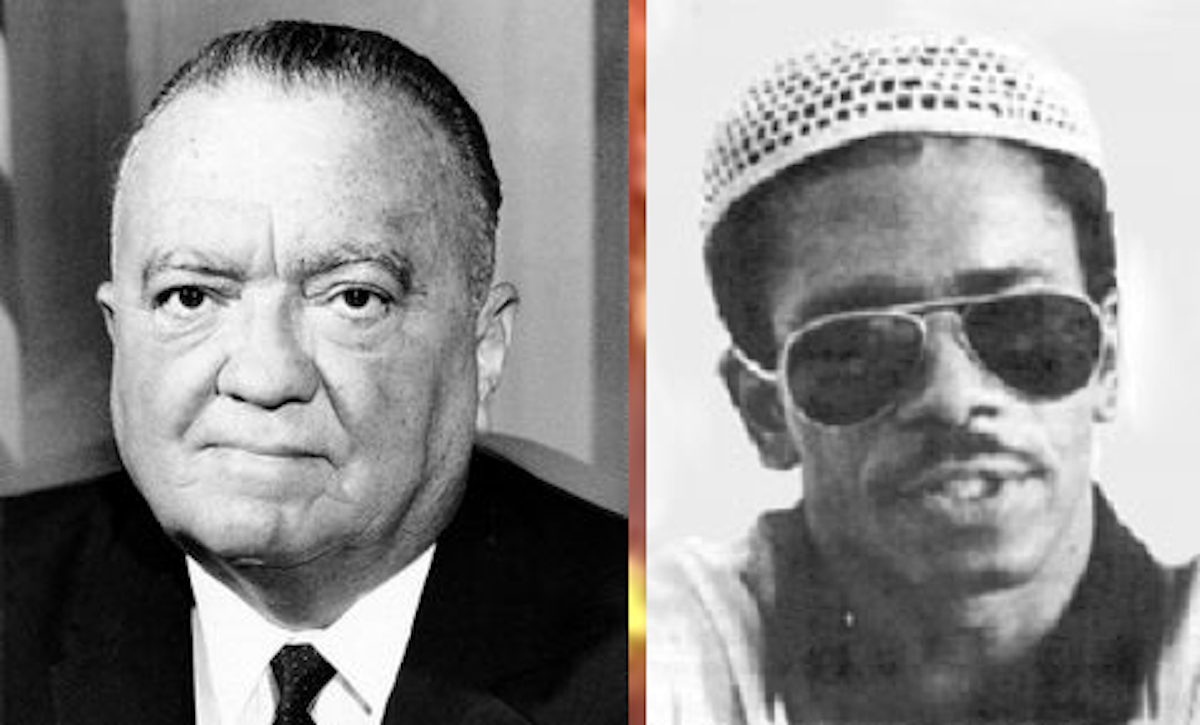

The FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover used Cointelpro to harass and break up Maxwell Stanford’s RAM movement. Photos courtesy of findagrave.com and blackpolitics.org.

When the FBI was spying on the civil rights movement, one of its early targets was a man then known as Maxwell Stanford. Now he just goes by Doc, as described in a GoFundMe page asking for assistance with medical costs relating to a series of strokes.

Stanford changed his name to Dr. Muhammad Ahmad as a founding member of the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), a Black nationalist organization that preceded the Black Panther Party. As detailed in hundreds of pages of declassified documents from the FBI’s archives, RAM was used as a sort of test case by an FBI program for how to watch and harass civil rights and Black nationalist groups throughout the 1960s.

In the summer of 1967, members of RAM were subjected to some of the early observation and intimidation campaigns that made up the bureau’s Cointelpro program. “The Counterintelligence Program was initiated in August, 1956, for the purpose of disrupting, embarrassing, and exposing the Communist Party, USA, and related organizations,” an FBI official wrote in a memo from 1965, recommending that the program be expanded to include the Ku Klux Klan. The program expanded again in 1967 to watch groups like RAM.

But the FBI was never in a hurry to acknowledge the program publicly. As FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover wrote in this letter to a Pittsburgh special agent in charge in 1968 who sought permission for an operation, public revelation of the program would hold a “possibility of embarrassment to the Bureau would be too great in this type of situation.”

The leaders of Philadelphia-based RAM, which briefly included Malcolm X, had high hopes of being a national revolutionary group, but it remained mostly a collection of academics and activists. Its chapters put out magazines and books and led protests on local issues, but RAM never attracted the following or made the impact of earlier civil rights groups.

But the FBI saw in RAM a relatively simple target that also was one of a new breed — a “hate-type” group, as outlined in a 1968 memo from the director — and the bureau expanded Cointelpro to attack. “The purpose of this new counterintelligence endeavor is to expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize the activities of black nationalist, hate-type organizations and groupings, their leadership, spokesmen, membership, and supporters, and to counter their propensity for violence and civil disorder.”

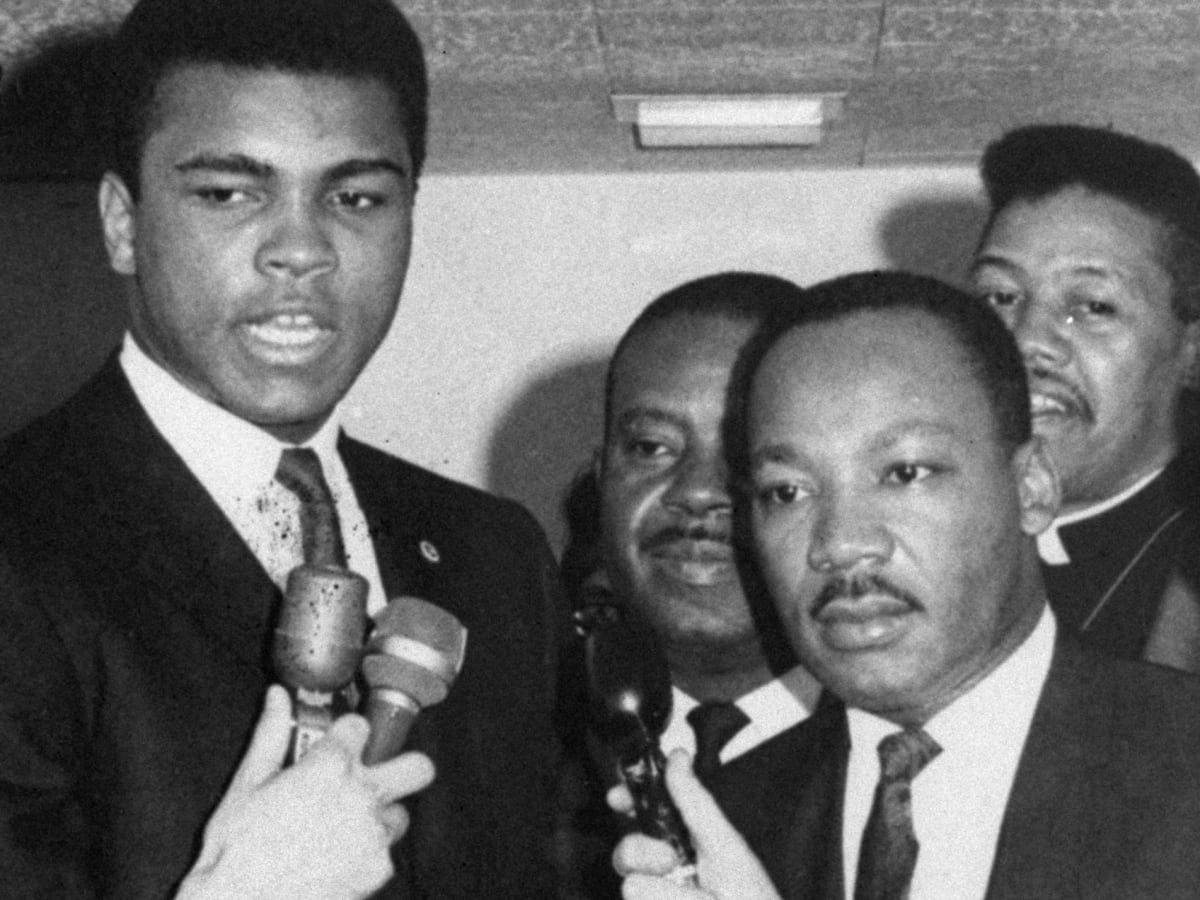

Hoover believed that Black groups formed in the mid-to-late 1960s were more prone to violence and took a more confrontational style than previous civil rights-focused groups, such as those led by Martin Luther King Jr.

FBI documents reveal there also were concerted efforts to target the leaders of these groups, that even went as far as using a comic strip to portray them as “living the good life,” and placing harassing phone calls to their homes and places of employment.

One memo from February 1968 asks permission to write and call leaders like Stokely Carmichael, H. “Rap” Brown, and four other redacted individuals at their home and work addresses and phone numbers “for the purpose of disruption, misdirection and to attempt to neutralize and frustrate the activities of these black nationalists.”

Carmichael eventually fled the US, and Brown is serving a life sentence for the 2000 murder of a sheriff’s deputy in Georgia.

In a Cointelpro document from 1967, the young Maxwell Stanford is explicitly named alongside three other “rabble rousers” on page 4 of the file, with Carmichael, Brown, and Elijah Muhammad. The file from FBI archives details FBI operations against them for more than 100 pages.

In later orders to FBI offices across the country, Hoover uses the operations against RAM as an example of Cointelpro’s success. Hoover writes “The Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), a pro-Chinese communist group, was active in Philadelphia, Pa., in the summer of 1967. The Philadelphia Office alerted local police, who then put RAM leaders under close scrutiny. They were arrested on every possible charge until they could no longer make bail. As a result, RAM leaders spent most of the summer in jail and no violence traceable to RAM took place.”

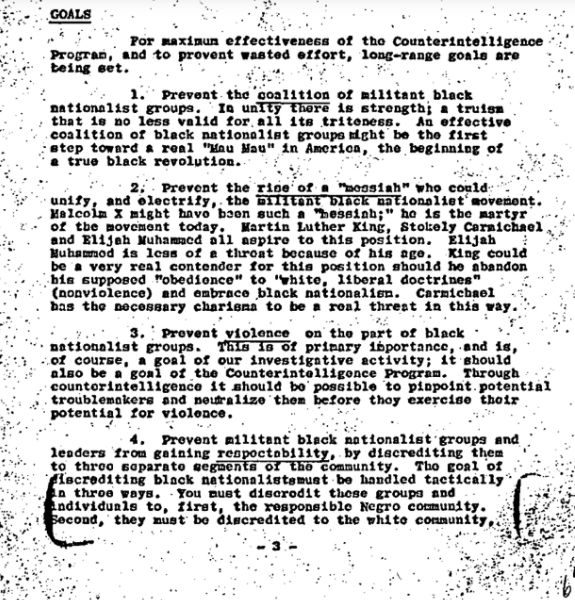

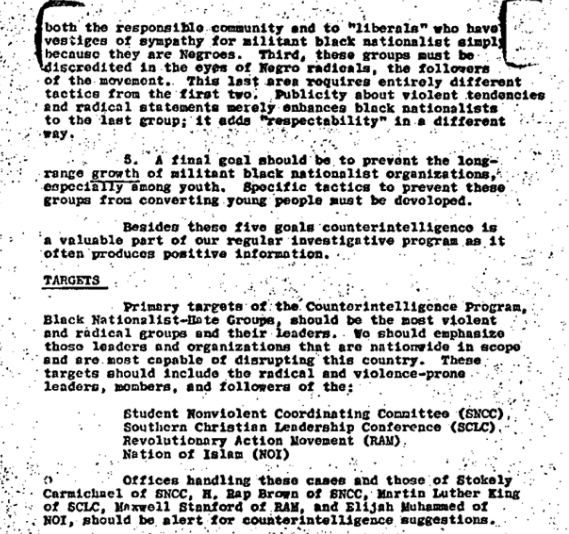

Using RAM as a template, Hoover outlined five goals for Cointelpro’s expansion:

1. Prevent the coalition of militant black nationalist groups. […] An effective coalition of black nationalist groups might be […] the beginning of a true black revolution.

2. Prevent the rise of a ‘messiah’ who could unify, and electrify, the militant black nationalist movement. […] King could be a very real contender for this position should he abandon his supposed ‘obedience’ to ‘white, liberal doctrines’ (nonviolence) and embrace black nationalism.

3. Prevent violence on the part of black nationalist groups. This is of primary importance, and is, of course, a goal of our investigative activity; it should also be a goal of the Counterintelligence Program.

4. Prevent militant black nationalist groups and leaders from gaining respectability, by discrediting them to three separate segments of the community. […] You must discredit these groups and individuals to, first, the responsible Negro community. Second, they must be discredited to the white community. […] Third, these groups must be discredited in the eyes of Negro radicals, the followers of the movement.

5. A final goal should be to prevent the long-range growth of militant black nationalist organizations, especially among youth.

By 1969, RAM mostly had dissolved, but the FBI continued its harassment of civil rights organizations until 1971. After a serious leak, in which several senators and civil rights organizations were sent documents outlining abuses against them by the bureau, the US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence was born. Known initially as the Church Committee for its chairman, Sen. Frank Church, D-Idaho, committee hearings put the FBI and multiple other agencies such as the CIA in hot water with the American people.

The Church Committee hearings first subjected US government agencies to oversight and adherence to constitutional rights. Though these agencies have overstepped over the years, the Intelligence Committee now exposes abuses, such Abu Ghraib, closer to when they happen.

Cointelpro-like activities aren’t over. The Intercept has reported how the US Department of Homeland Security began monitoring Black Lives Matter protesters in 2015.

Read Next:

Lauren Coontz is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. Beaches are preferred, but Lauren calls the Rocky Mountains of Utah home. You can usually find her in an art museum, at an archaeology site, or checking out local nightlife like drag shows and cocktail bars (gin is key). A student of history, Lauren is an Army veteran who worked all over the world and loves to travel to see the old stuff the history books only give a sentence to. She likes medium roast coffee and sometimes, like a sinner, adds sweet cream to it.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.