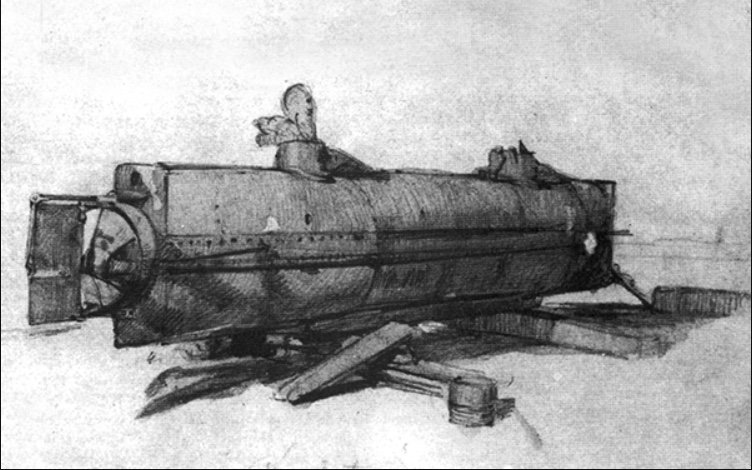

The H.L. Hunley, built to break Union blockades. Photo of the 1863 painting by Conrad W. Chapman, courtesy of the American Civil War Museum.

Silently gliding through frigid February water, the Confederate submarine H.L. Hunley stayed just under the surface as it approached its prey. As it breached the surface, sailors aboard the Housatonic, a Union sloop-of-war, may have thought it looked like a whale coming up for air. By the time the Union sailors realized their mistake, it was too late.

Using a “spar torpedo” — an explosive spear that the sub rammed into its target — the Hunley blew a hole in the Housatonic, which sank beneath the Atlantic in less than five minutes. Most of its sailors survived, with just five out of a 155-man crew lost in the Feb. 17, 1864, attack near Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina. But the crew of the sub that fired the shot actually fared worse. The Hunley never returned to port, with all eight mariners of the Confederate Navy lost for 131 years.

The Hunley was the first submarine to see combat in America, even though it was deadliest to its own crew. Built in 1863 to run Union blockades of Confederate ports, the Hunley’s only successful combat action was against the Housatonic, causing those five casualties. But during its brief career in the Confederate Navy, the Hunley killed 21 Confederate sailors, including the eight lost in the attack on the Housatonic.

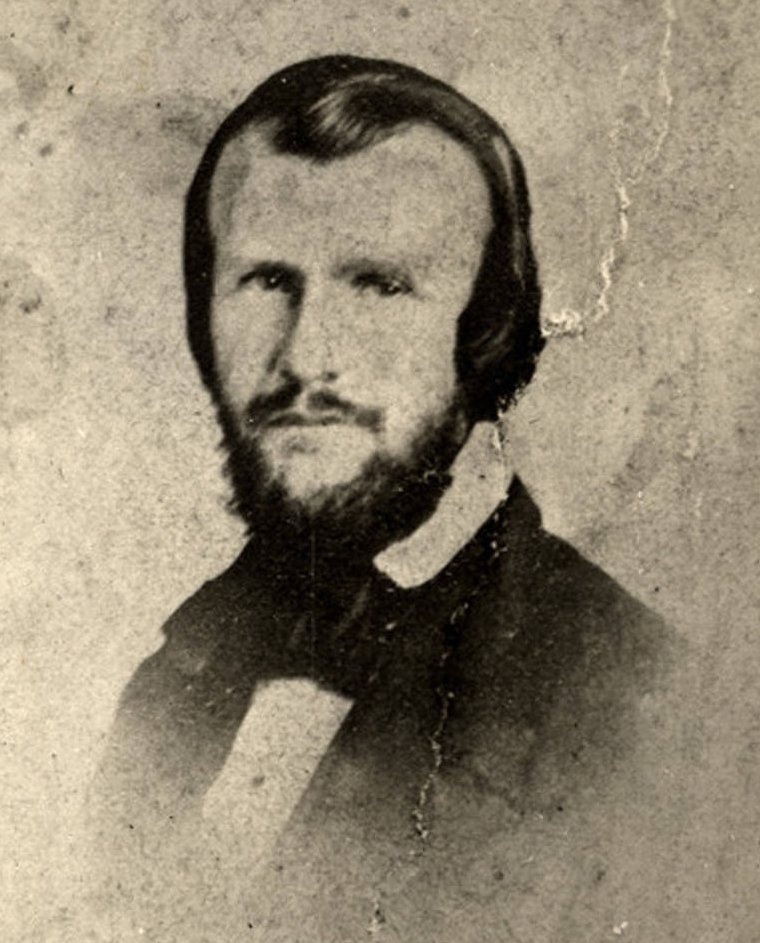

Originally built by James McClintock and Baxter Watson, the Hunley took its name from a decidedly unromantic source: the man who funded the whole thing, Horace L. Hunley, a wealthy Confederate lawyer and merchant. Upon successful demonstration, the submarine was sent immediately to use against the Union blockade off the coast of South Carolina in August 1863.

However, the Hunley quickly built a reputation as a death trap. It sank for the first time on Aug. 29, before ever leaving its moorings at the dock, killing five of its eight crewmen. John Payne, the Confederate captain who commanded the sub that day, was among the survivors.

The ship was raised, but it sank again two months later, on Oct. 15. A demonstration dive had been arranged to allow the Hunley to submerge under another ship, the Confederate bomber CSS Indian Chief.

It got the demonstration half right.

The Hunley submerged and went below the other vessel. It just never came up. Again, salvagers pulled it out of the water.

According to the Hunley Museum website, the dive ended in terrifying final moments for those on board. “Rescuers reported the forward ballast tank valve had been left open, allowing the submarine to fill with water,” according to museum history. “The sub’s keel weights had been partially loosened, which suggested the crew realized they were in danger, but not in time to save themselves.”

All eight crewmen were killed, including Horace Hunley, who had captained the submarine himself for the demonstration, making the Hunley possibly the only ship in naval history to kill its namesake.

The Feb. 17, 1864, sinking of the Housatonic was the Hunley’s first and last combat engagement. But as the Hunley sank to the floor of the Atlantic for the third and final time, it did so as the first submarine in history to successfully destroy another vessel.

Missing for 131 years, the Hunley’s final sinking was a mystery many tried to solve, as both civilians and government searchers looked for the wreck. In 1995, a team from the National Underwater and Marine Agency, led by legendary adventure novelist Clive Cussler, discovered it. Inside, artifacts revealed a time capsule of life as a Confederate soldier during the Civil War.

The Hunley’s captain, Lt. George E. Dixon, and the rest of the men aboard, volunteered for the mission. When the Hunley was found, the body of each man was found at his station, making identification of the remains easier. Sediment in the submarine left their bodies remarkably preserved, with one man’s brain still intact.

Hunley’s artifacts ran the gamut of the daily life of a Confederate soldier, with random buttons from different campaigns, differently colored clothes and boots, and even ornate jewelry. Notably, salvagers found a gold coin with a bullet indentation that belonged to Dixon. It had stopped a bullet while in his pocket at the Battle of Shiloh. Dixon appeared to have engraved the coin with the date of the battle, “April 6th 1862. My life Preserver G. E. D.”

Researchers continue to debate why the Hunley sank. The sub was found with damage to much of it, including the hull, propellers, and conning tower, as well as oddities like the forward conning tower being unlatched.

Was the Hunley too close to the torpedo explosion? Was it trapped by the tides, did it blindly collide with something, or did the Housatonic’s sailors get off a lucky shot? Researchers and nautical archaeologists at the Friends of the Hunley hope to answer these questions with more research.

The remains of the Hunley’s final crew were buried in April 2004 at Magnolia Cemetery in Charleston, South Carolina, resting next to the 13 other crew killed during the previous accidents involving the submarine.

Read Next: Why This Heroic Navy Diver Was Awarded the Medal of Honor After a Submarine Sank

Lauren Coontz is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. Beaches are preferred, but Lauren calls the Rocky Mountains of Utah home. You can usually find her in an art museum, at an archaeology site, or checking out local nightlife like drag shows and cocktail bars (gin is key). A student of history, Lauren is an Army veteran who worked all over the world and loves to travel to see the old stuff the history books only give a sentence to. She likes medium roast coffee and sometimes, like a sinner, adds sweet cream to it.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.