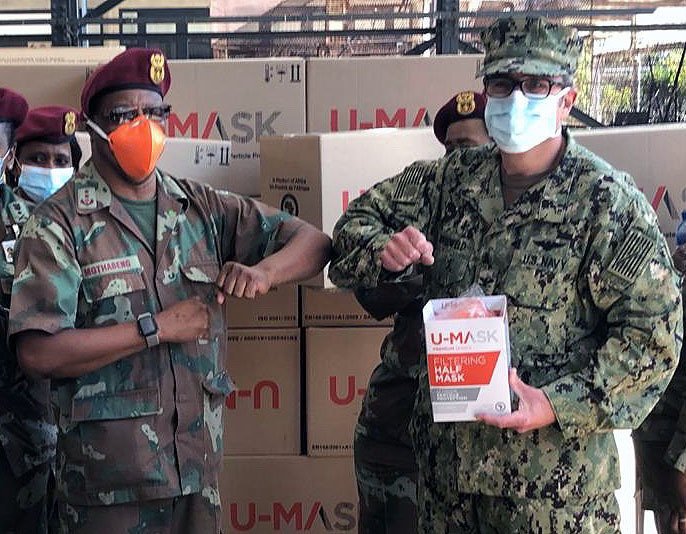

Photo courtesy of US Army.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an international event that will define 2020 and likely an entire generation around the world. At the time of publication, the “novel coronavirus” has infected over 2.8 million people, and killed over 200,000. The implications of this virus are far reaching, extending well beyond the medical sphere and into the economy, diplomacy, and national security of the United States.

If you’ve been watching the news, you’ve likely heard many politicians and pundits talking about the need for a “whole of government” or “full power of the government” approach to resolving the COVID-19, or coronavirus, pandemic. But what does that mean for us as individuals?

In a military or political setting, the term “whole of government” usually refers to the four instruments of national power that countries use to promote and sustain their national security and grand-strategic interests. Those elements are diplomatic, informational, military, and economic — collectively known by the acronym DIME.

DIME (as well as its derivatives DIMEFIL and MIDLIFE) is a useful construct to consider the national-level impacts of the ongoing COVID-19 crisis and to consider what those impacts mean to our future as a nation.

The first of these elements is diplomatic powers, which are the means by which a sovereign nation seeks to advance its agenda or influence the agenda of others through the use of politics, policy, and negotiation.

Diplomacy is a “people” business, and most people-related business is best conducted face to face. The coronavirus crisis and its requisite quarantines and “social distancing,” of course, make this much more complicated.

For example, the U.S. State Department has dramatically scaled back operations, which impacts everything from visa applications and liaison work to immigration. Passport services are almost entirely shut down, except for extreme situations like a “qualified life-or-death emergency.” Moreover, for the first time in its history, the entire Peace Corps has been recalled and is shutting down its overseas activities, and USAID has shifted much of its effort to fighting the virus.

Other events that promote positive relationships between nations, such as the Olympics, have been postponed or outright canceled. COVID-19 also has implications for upcoming elections, both in the U.S. and around the world, as people hold their leaders accountable for their COVID-related actions — or inaction, in some cases.

The pandemic is contributing to political instability in places particularly hard-hit by COVID-19, such as Iran. It is not unreasonable to assume that there may be major leadership changes in key diplomatic positions around the world in the aftermath of the crisis.

One of the governing precepts in international relations theory is the concept of anarchy. This isn’t the “riot in the streets” kind of anarchy that most of us are used to hearing about; it simply means that there is no global supreme entity, or hegemon, that can boss around all the other sovereign states. While some global superpowers, such as the U.S., can often influence other nations and global decision-making bodies such as the United Nations, at the end of the day sovereign states are going to do what they have to do in order to survive. Because of its inherent anarchy and the desire to survive, the world is a self-help system in which each nation can only count upon itself in times of crisis.

What we are seeing in this current crisis is a (presumably temporary) retreat from close political working relationships, agreements, and the flow of people and goods. That increases the effect of anarchy and reduces the level of positive interactions between nations and peoples, which negatively affect diplomacy, trade, information exchanges, and military cooperation. Due to a drop in diplomatic interaction, we’re also seeing the creation of a patchwork of policies, both within the U.S. and overseas, that further complicate efforts to protect populations and combat the spread of the disease.

Following the diplomatic element is the concept of informational powers. This refers to the production, acquisition, and protection of information that can be used by a country to achieve its aims, or be used against it if uncovered by an adversary.

In terms of DIME, the coronavirus’ impact on information is, arguably, the most interesting. From the very beginning, information about COVID-19 has been incomplete, nonexistent, or flat-out wrong. There now appears to be worldwide consensus that China lied about the severity of the outbreak in the crucial early days of the crisis and continues to do so to this day. While it is generally accepted that the virus originated in China’s Wuhan province, most likely at a livestock market, China has engaged in concerted and protracted blame shifting, claiming that the U.S. Army is responsible for the origination and spread of the virus. Iran, too, has engaged in large-scale finger pointing as their country reels from the effects of widespread infection.

The world’s foremost source of information, the internet, is also being negatively impacted. A major increase in demand is slowing down internet access speed, and some sites are not accessible in all areas, possibly due to government interference. This in turn affects the public’s ability to keep itself informed as the crisis unfolds. Of course, simply having access to more information doesn’t necessarily mean that people are better informed. It sometimes means that misinformation gets to many more people that much sooner.

Part of what is driving nations from being more forthcoming about COVID-19 can be explained by the international relations concept of relative gain. This concept stems from the belief that power and influence on the world stage is a “zero sum game,” in that there is an affixed amount of power and any gain from one country, particularly a powerful rival, comes at the expense of one’s own. So sharing information, especially information that is possibly embarrassing or detrimental to one’s standing in the world, is done reluctantly, if at all.

Relative gain also explains why some countries are unwilling to share information, or to engage in beneficial relationships on trade and other matters. It’s not because they won’t be better off but because other countries might be more better off. You can see some of this in domestic policies as well: one party proposes a bill that benefits both sides of the political divide, but the other side opposes it because they perceive that they are gaining less relative to their competitors.

The third element of DIME, military powers, includes the active, reserve, and paramilitary forces that are trained, equipped, and empowered by an organization to utilize force on its behalf. Used chiefly outside of a country’s home territory to act against other nations, or within a nation’s borders to provide internal security.

Some argue that the “M” component of DIME is the most important, pointing out that if you take the M out of DIME, you simply have DIE, and “DIE” is probably not something we want to do as a nation. President Donald Trump declared war on COVID-19, and generally speaking the military is the best organization to fight a war. But in this kind of war, the military is best at being a supporting element instead of the main effort.

Despite the fact that COVID-19 is largely a medical and political problem, the military does have a large role to play. The National Guard, reserves, and/or active duty force might be called upon to provide disaster support to civil authorities (DSCA), provide medical assistance, maintain order, and deliver much-needed supplies.

Like the rest of the world, the U.S. military is feeling the effects of COVID-19 as well. Recruiters are being forced to work from home, which dramatically reduces their effectiveness. Professional military schools are on hold, as is the military’s regular “permanent change of station” process that moves service members across the nation and around the world. And since troops are largely confined to quarters and restricted from gathering in any appreciable numbers, readiness and training are taking a big hit.

In international relations theory, there is a concept called the security dilemma, which in simple terms is the belief that the steps that one country takes to make itself more secure inevitably make other countries feel less secure, which in turn causes other countries to raise their level of security — and on and on.

Finally, there are the economic powers that leverage the worldwide market to exchange goods and services and enrich the nation and its citizens.

COVID-19 is causing markets across the world to take huge financial hits. The U.S. stock market has plunged in value, following a worldwide trend. Investors are very pessimistic about the volatile markets, and some people are seeing their life’s savings evaporate. Fuel prices are lower than they have been in decades, and some oil-rich nations that depend on fossil fuels as their main source of income will be hard-pressed to make budget and keep their people happy. This increases the possibility of economic unrest and conflict around the globe.

Dramatic drops in trade are also negative indicators for relationships between nations. In international relations theory, there is a concept known as the Trade Expectation Theory that explains what could happen between nations when they stop trading with each other. In simple terms, TET explains that countries that foresee high levels of future trade with each other are much less likely to go to war. When the expectation of future trade goes down, the potential for conflict goes up.

The U.S. and China were major trading partners — and rivals — with each other prior to the pandemic. Now that the expectation of future trade is lower than it was in the past, there is the possibility of increased tension and potential conflict between the two nations.

While the impact of COVID-19 on all of the U.S.’s instruments of national power has been profound, there are numerous productive policies and practices being initiated across the country and around the world.

The State Department and various NGOs are coming up with creative ways to conduct person-to-person business without being face to face. USAID announced tens of millions of dollars to support COVID-related “critical interventions” in developing countries, and Congress has approved a stimulus and recovery package worth trillions of dollars.

The intelligence community is finding creative ways to keep up its work outside the traditional confines of a classified workspace, and internet-based companies are increasing capacity and streamlining their services in order to provide much-needed bandwidth. The military is finding ways to keep its troops trained, prepared, and engaged, and businesses large and small — both domestically and internationally — are finding ways to stay in business and promote commerce in these trying times.

Whether the COVID-19 crisis resolves quickly or through a long, slow slog, the implications for national security are severe. While a cure might be on the horizon, the impacts of what has already occurred will be felt for years to come. The U.S.’s diplomacy, information and intelligence apparatus, military forces, and, most significantly, its economy, have already sustained a heavy blow even though the realization of its full impact may take years. Fortunately, it is unlikely to be a fatal blow to our nation or to any of its instruments of national power.

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Faint is a military intelligence officer with the United States Army and holds a master’s degree in International Relations from Yale University. He taught International Relations at West Point for three years, and also served in the 5th Special Forces Group, the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, and the Joint Special Operations Command, to include seven combat deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. You can reach him at [email protected], and read more of his work on West Point’s Modern War Journal or on The Havok Journal. This article reflects his personal opinion based on his education and experience, and is not an official position of the U.S. Army or the U.S. Government.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.