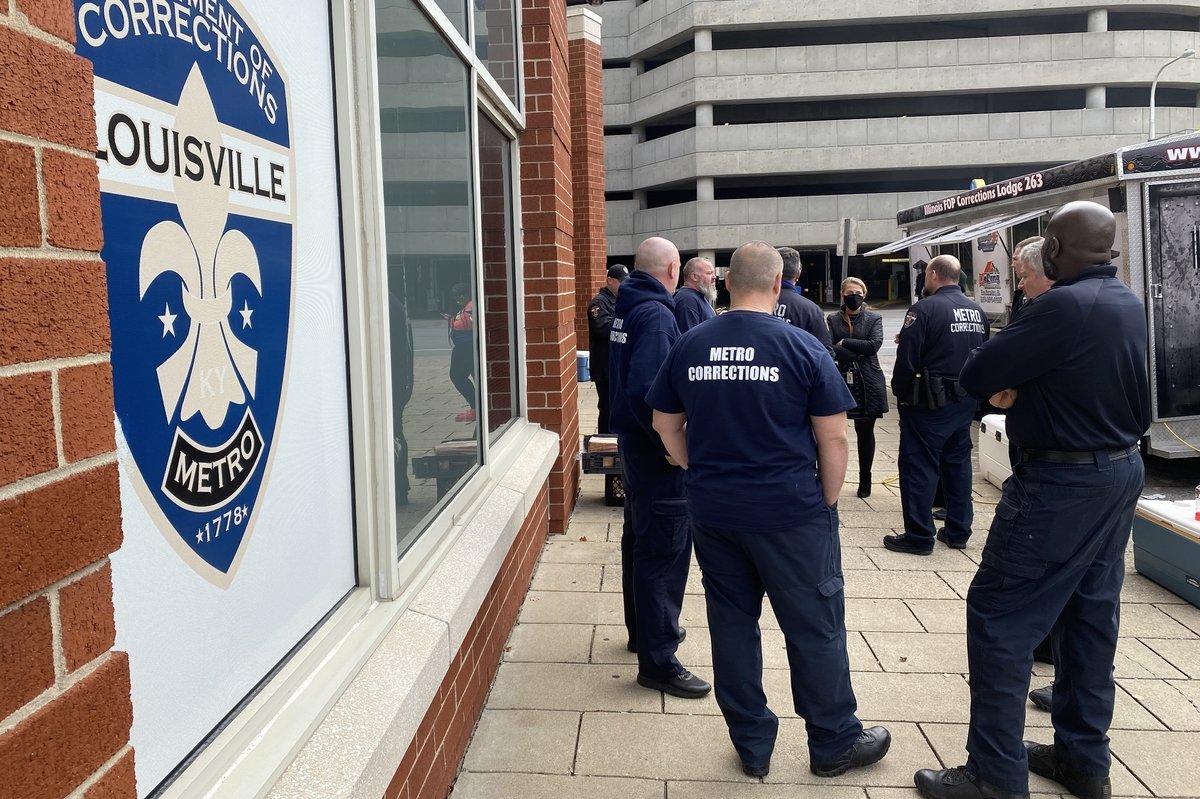

Louisville Metro Department of Corrections officers gather for a free lunch on Nov. 2, 2021. Dwindling numbers of job applicants want to become prison guards nationwide. Critics point to low wages, rough conditions, and increased competition from the private sector for a hike in CO vacancies in Kentucky and other states. Photo by Carl Prine/Coffee or Die Magazine.

There are 14 in line and more continue to drift down from the Louisville Metro Department of Corrections to get the free chow.

It’s 11:33 a.m. on Nov. 2, 2021. There’s a food truck at the corner run by volunteers from Illinois Fraternal Order of Police Corrections Local 263. They’re short fries and it’s so cold the officers’ breaths puff silver in the Kentucky air. But at least it quit raining.

The burgers are a gesture of nationwide solidarity for correctional officers in a moment of crisis. Increasingly in county, state, and federal prisons, dwindling numbers of people are willing to brave bad pay, long hours, and potentially violent conditions that corrections officers face overseeing inmates.

COs are quitting across the country in record numbers, and facilities are struggling to fill vacancies.

Local 263’s president, Scott Ward, who retired in late 2020 as a sergeant after 26 years inside the Logan Correctional Center near Springfield, looks up at the walls of the Louisville lockup and sums it all up: “It’s a shit show here.”

Ward once had to deal with a convicted murderer who pulled her eyeballs out of her own sockets, so he’s seen some crazy things. But he hasn’t seen much that’s as bad as LMDC.

“We’re already in an emergency mode, limiting the movement of inmates,” said LMDC Sgt. Daniel Johnson, a first-shift jail guard and the president of FOP’s Local 77, the union representing the sworn officers who serve as Louisville’s COs.

He’s a 17-year veteran of the lockup and he frets the overworked staff might reach their “tipping point” by Christmas, and the jail will cease to function.

“Every shift is already on lockdown, but no one’s calling it a ‘lockdown.’ We’re in a crisis,” Johnson told Coffee or Die Magazine.

“I’m encouraging everyone to never give up. Anyone in this field knows that we’ve gone through a lot of ups and downs over the years, that our careers can be like roller coasters, but this is the worst I’ve ever seen,” he said.

City officials didn’t return messages from Coffee or Die, but the math driving the jail crisis isn’t in dispute. The jail recently brought on a dozen new COs, along with 10 other rookies earlier in the year.

The problem: 61 veteran officers exited the lockup between January and November, leaving 135 vacancies. It’s the fourth year in a row where departures outnumbered gains. The department estimates 35% of its CO positions are unfilled.

Nationwide, the figures aren’t much better, with nearly every state and federal corrections agency reporting rising vacancies and fewer applicants willing to become COs.

By early November in Wisconsin, state officials advertised 1,050 open staffing positions across the system, about a 23% vacancy rate. The shortages are critical at two of the state’s five maximum security prisons, with 47% of the staff positions unfilled at Waupun Correctional Institution and 43% vacant at Columbia Correctional Institution.

Testifying before Kansas lawmakers in early November, state Department of Corrections Secretary Jeff Zmuda warned that he has more than 400 vacancies in his system, a problem he predicted will continue to worsen as officers bolt for the private sector.

The CO shortage in Florida is so acute that officials shuttered three of its state prisons. Texas closed six.

“There are consequences to these shortages. The most obvious are that they begin to compromise the safety and security of the institutions,” said Megan Quattlebaum, the director of the nonprofit Council of State Governments Justice Center. “When they’re not staffed the way they need to be, the programs that keep incarcerated people occupied, that provide rehabilitation and job training, will get cut for the security mission.

“And those programs are important because the vast, vast majority of incarcerated people will get out and return to their communities. One key consequence of these shortages is that we have less ability to prepare people for success on the outside. They’re not charting paths to success.”

In August, the Indiana Department of Correction reported 1,549 vacancies, a footnote to a lingering crisis that forced the governor to call up the National Guard to fill prison positions. That formula has been repeated in six other states over the past two years, including Massachusetts, Ohio, and Montana.

According to Indiana National Guard spokesman Master Sgt. Jeff Lowry, up to 270 Guardsmen filled in for staffers in Miami, Pendleton, and Westville prisons in 2020, although they’re down to 80 troops now. They patrol the exterior portions of the prisons, augment medical and administrative services, and monitor security desks.

“As always our Indiana National Guardsmen stand ready to help our fellow Hoosiers and Americans during the pandemic, natural disasters, and overseas deployments,” Lowry told Coffee or Die.

Indiana Department of Correction officials didn’t return numerous telephone and email messages seeking comment. Neither did state lawmakers who oversee the prison system and earmark how much Indiana’s COs get paid.

The state prisons start trainees off at $23,582 per year, according to the agency’s official job board. That’s $11.33 per hour, roughly what fast food restaurants pay Hoosier teenagers.

Nationwide, 405,870 men and women toil as correctional officers and jailers, and their median hourly wage is $22.79, nearly twice Indiana’s starting pay, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“When you see systems underfunded, the person in charge would like to add staff, but the person in charge often can’t because of that,” said John Wetzel, the highly respected Pennsylvania corrections secretary who retired on Oct. 1 after 10 years at the helm.

During his tenure, Wetzel slashed the number of inmates from nearly 52,000 to 37,000; broadened their access to psychiatric care; and made sure that nearly 90% of them were vaccinated against COVID-19, part of a larger series of reforms designed to keep the global pandemic from ravaging prison populations and the staffers that guard them.

Wetzel also worked with the COs’ union, two governors, and the state legislature to hike CO pay. The typical guard in a Keystone State facility earns more than $63,000 per year, about $16,000 above the national average, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Wetzel estimates the CO vacancy rate in Pennsylvania’s state system at below 3%, despite the COVID-19 epidemic that caused thousands of guards to miss work. He calls his state’s correctional officers “heroes.”

“COVID-19 stressed the system,” Wetzel told Coffee or Die. “You have to keep your staff healthy physically and mentally, but think about what the last year was like. You have professionals who were under immense pressure even when they weren’t at work.

“They were home schooling kids because schools were closed. Shops were closed. Their churches were closed. They still came to work.”

Texas Department of Criminal Justice spokesman Robert C. Hurst echoed Wetzel, telling Coffee or Die that the pandemic exacerbates CO recruitment campaigns already reeling from “economic surges and competing employment opportunities” in the Lone Star State.

But he said Texas lawmakers also recently approved a 3% pay hike for COs and other staffers at the state’s 23 maximum security facilities, where officials record the highest turnover rates. And in every prison, officials restructured the career ladder so COs get pay raises earlier and get ahead faster, innovations they hope helps retention.

“We understand that there is no one solution to staffing but we will continue to find new and creative ways to fill critical positions,” Hurst said.

At the beleaguered Louisville Metro Department of Corrections, the dwindling number of COs means personnel expect to work 16-hour days, leaving little time for family. On Halloween, everyone on first shift was forced to work late, so COs missed trick-or-treating with their kids.

There were 1,533 inmates behind bars in Louisville on Oct. 20, and nearly three out of every four were charged with violent crimes. Sgt. Johnson told Coffee or Die the guard-to-inmate ratio stands at roughly one to 80, although that’s unequally distributed throughout the jail.

In the mental health wards, one guard watches over 50 inmates. In the most violent cell blocks, one CO might be overseeing 230 prisoners.

CO wages in Louisville start at only $17.41 per hour. Johnson said the nearby Walmart offers new stockers $22. He’s calling on the city to get closer to private sector wages to help stem the exodus of jail guards.

Johnson told Coffee or Die that the CO shortage has forced his lockup to disband its intensive oversight of inmates on suicide watch, and there are other security worries. COs used to record one inmate-on-inmate assault per month, but with so many staff vacancies it’s approaching 10 per day, and COs are finding more shanks and other weapons, he said.

“You’re asking someone to risk his or her life for $17 a hour,” Johnson said. “If something goes wrong in Louisville, you’ve got a can of pepper spray and your best negotiating skills. Good luck with that.”

This article first appeared in the Winter 2022 print edition of Coffee or Die Magazine.

Read Next: Police: Vermont Man Attacked 2 Troopers With Excavator

Carl Prine is a former senior editor at Coffee or Die Magazine. He has worked at Navy Times, The San Diego Union-Tribune, and Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. He served in the Marine Corps and the Pennsylvania Army National Guard. His awards include the Joseph Galloway Award for Distinguished Reporting on the military, a first prize from Investigative Reporters & Editors, and the Combat Infantryman Badge.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.