The Courier From Warsaw: Jan Jeziorański-Nowak’s Fight For Polish Independence

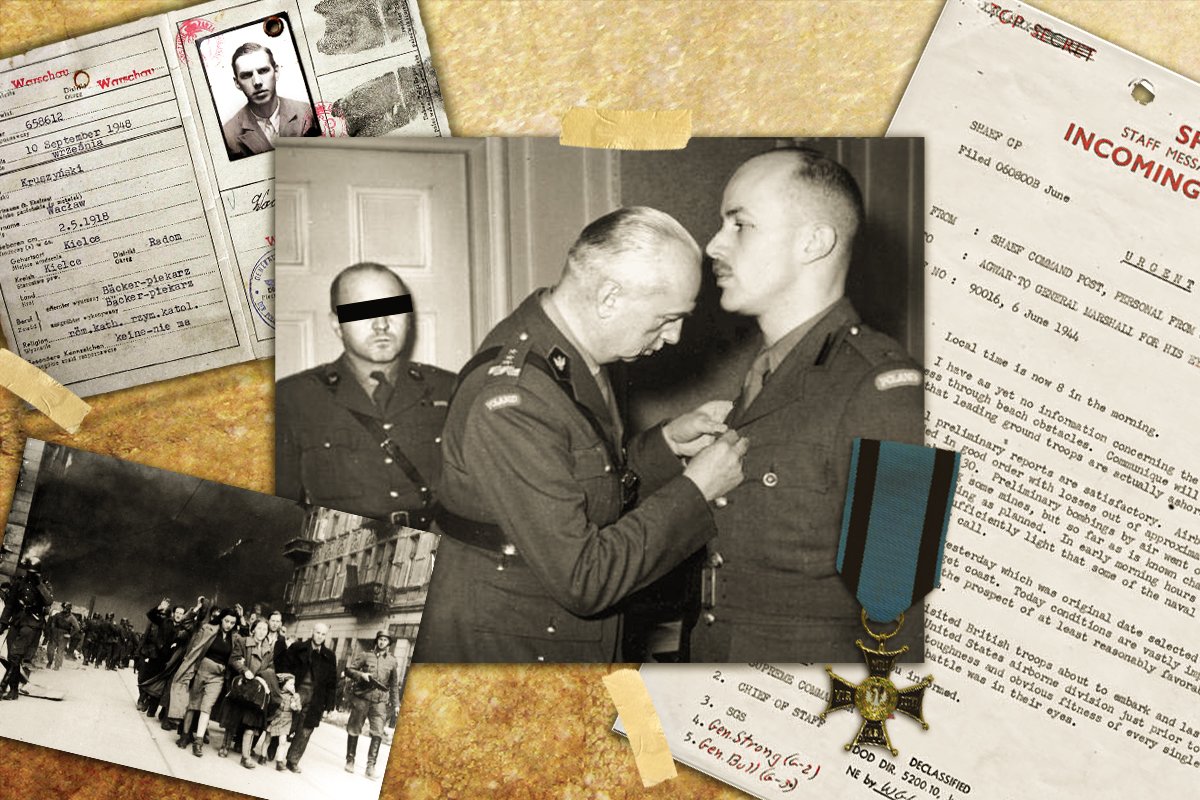

Zdzisław Jeziorański, Jan Kwiatkowski, codename “Janek,” codename “Zych,” Jan Nowak — these were a handful of noms de guerre used by the famed Courier of Warsaw while working for the Polish Underground during World War II. His journeys took him across the borders of several European nations, some sympathetic to the Third Reich, others drafting schemes to undermine it, and a few neutral to the evolving circles in which daily espionage occurred on the biggest city streets.

Nowak disguised himself as a railwayman on a train through Nazi-occupied Poland, boarded a fishing vessel in a discreet compartment bound for Sweden, hid in temporary safe houses where passwords were exchanged for safety — the job always dangerous, the toll overshadowed by political intrigue. Jan Nowak worked tirelessly, both as an emissary and as a radio broadcaster where the fight to keep Polish sovereignty and independence on the world’s stage was silhouetted by the three major Allied powers.

Nowak’s lifelong service from the beginning of World War II through the Cold War earned him many accolades. He was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Virtuti Militari (the Polish equivalent of the Medal of Honor) and praise from U.S. President Bill Clinton, who awarded his dedication with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Poland’s unsung hero used his influence for good at a time when many suffered.

Scholar to Soldier

Before he gained notoriety as a diplomatic mediator between Allied nations’ highest officials during the largest war, Nowak (then called Zdzisław Jeziorański) was a penniless student attending the University of Ponzan. It was 1932, and Poland’s economic depression was rampant, employment percentages had plummeted, and money from home was nonexistent. While studying economics, a professor named Edward Taylor gave this audacious 19-year-old from Warsaw a chance. Over time, he appointed Nowak as his senior researcher. Nowak’s life as an academic then progressed swimmingly as he obtained his doctorate and professional opportunities became available.

Nowak’s ancestors lived and fought during the First World War against the Germans, Russians, and Austrian Empire. Their fight for sovereignty and independence ended in 1918 after 123 years. The turmoil amongst the region grew unstable behind the scenes, the memory not easily forgotten by either side. By September 1939, Nowak’s life as a scholar was interrupted for what he naively assumed was a temporary adventure in soldiering.

Nowak writes in his memoir, “The Courier From Warsaw,” how confident he and his teammates were in his nation’s military. That mindset changed instantly when news came in of German occupation of the Polish cities Poznań, Katowice, Kraków, and Łódź. The war evolved in front of him at the small farmland village of Uscilug on the border of the Soviet Union.

In the span of a month, Nowak was shot at by a German patrol and twice was captured and escaped. The first occurred when his unit became separated and he was exposed alone in a field. He fled into a barn, chased by bullets, and was discovered hours later under a bail of hay by Austrians sympathetic to the Nazi regime. He was turned over to the patrol and nearly escaped fratricide when a diving Polish bomber dropped its ordnance on his position.

The explosion threw him into the air, and he was recaptured moments later, unscathed. The second escape occurred while ferrying a prisoner of war (POW) train to the Third Reich, where he and several other POWs controlled their own fate. They used the cover of darkness and a thick layer of fog to shield them as they jumped off. These two feats are minor compared to what he would later endure as a courier for the Home Army.

Action N & the Polish Underground

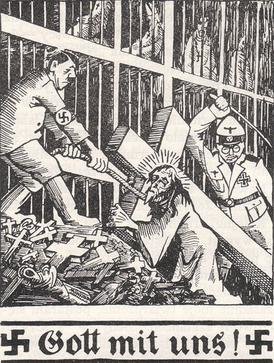

One of Adolf Hitler’s first tasks was diminishing the morale of Poland’s populace to ensure that resistance groups wouldn’t be formed to fight against the regime. Their tactics strictly operated using brutality and fear. Teachers, priests, physicians, academics, and even people suspected of the capability, were rounded up and executed under the order of Intelligenzaktion. Some 60,000 people were murdered because of their occupation. Poles vanished across the country with the assumption that they were taken to concentration camps as a part of the liquidation of ghettos.

Nowak returned to the home of his mother and older brother in Warsaw. The occupying Germans had confiscated radios, which was the only method many households used to receive news. Nowak has said that it was the biggest mistake the Germans made. If caught with a radio, punishment by death was announced to the public bulletin, often broadcast by German military vehicles with loudspeakers and carried out by shooting or hanging in the street. Those who committed to the Volksliste — siding with the Germans — were granted free use of radios. This led to the creation of clandestine groups and, ultimately, Nowak’s involvement in the Polish Underground.

Soon, efforts were in motion to go undercover to survive. The bylines of underground newspapers were codenames; Nowak used “Janek” beginning in October 1939. This evolved into broader participation with the brain-trust of Action N (Niemcy, Polish for “Germany” or “Germans”), a top-secret component of the Polish Underground that the Germans, the Polish public, nor select sections to include AK (Home Army) or ZWZ (Union for Armed Struggle, merged with AK) were aware of early on.

This psychological warfare unit distributed black propaganda pamphlets targeting select German officers marked “German only” or Nur für Deutsche. It was a slogan used in occupied countries, and Action N exploited it. A copy of Der Durchbruch, a pamphlet falsely published by German intelligence, contained scandals and abuses as if it were written from a high-ranking German elsewhere, except it was another form of propaganda from Action N that proved to cast doubt.

If caught with a radio, punishment by death was announced to the public bulletin, often broadcast by German military vehicles with loudspeakers and carried out by shooting or hanging in the street.

As the war progressed, Action N’s tactics, techniques, and procedures focused on surgical strikes because it kept people reasonably safe. Outside groups that operated indiscriminately with violence toward Gestapo or other Germans faced mass retaliation, putting their families and neighborhoods at risk.

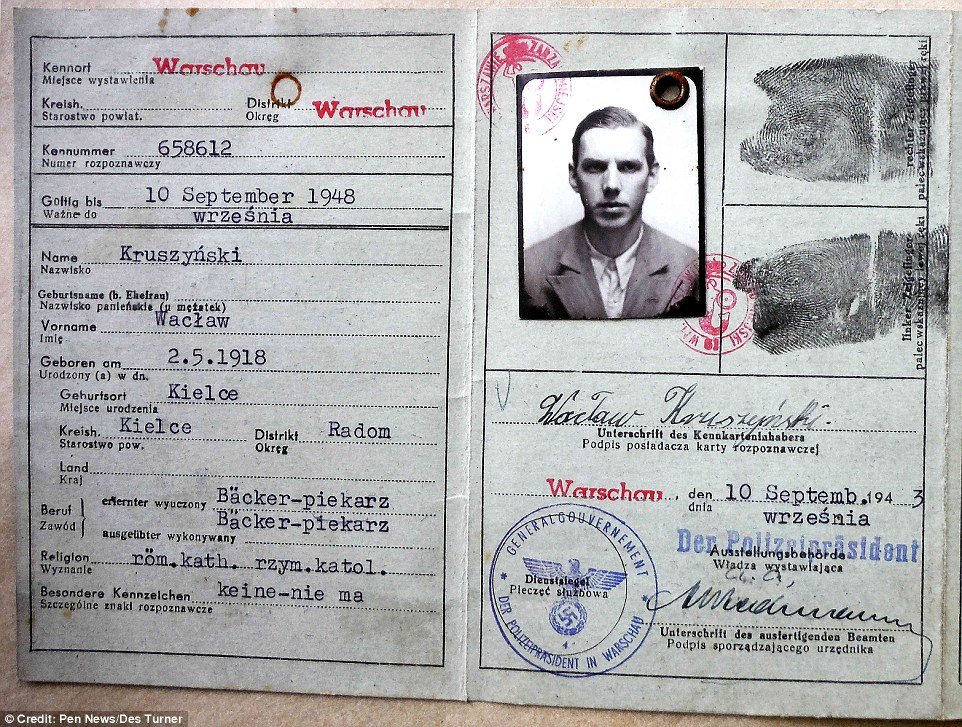

Action N’s network started small, and the risk was extraordinary. The unit was broken into four parts: Agents, where Nowak worked; Research and Intelligence; Editorial office; and Sabotage and Forgeries of German documents, letters, and orders. The only way to safely move across frontiers, within city streets, or aboard transportation systems was through trusted contacts, safe houses, and false identities. Fake names, fake home addresses, altered photographs, and authentic-looking papers were the standard. Members of the Polish Underground who continuously used the same route increased the risk of apprehension.

The Invisible Man

In the summer of 1942, Nowak’s took his first trip to Ponzan as a courier for the underground under the auspices of his dead friend, Jan Kwaitkowski, who was killed in the war. He was an official of the railway workshops. Weeks prior, Nowak rendezvoused with codename Wildcat (real name Stanislaw Witkowski) to arrange for the documents to be perfected; identity card and travel permit were exclusive to the other to cross frontiers.

With his new identity, he transported Action N literature and pamphlets marked in German for “book shop” and inserted them into German magazines aboard the train. Other reading material at the station, such as newspapers and books opened to a random page, had hidden material tucked in them to ensure the propaganda reached different parts of Germany. The tradecraft they practiced adapted on the fly. They acted as conductors arriving and leaving a shift for speed. But on the days when trains were late, the Gestapo often made conversation with railwaymen standing on the platform nearby.

Basic questions asked by German soldiers could expose them, as many in Action N did not speak any German and relied on their counterfeit documents. The safest travels were at night aboard “specials,” which were military trains transporting uniformed Germans and civilian-clothed soldiers on leave. As Action N gained mass circulation throughout Poland and into Germany, Nowak focused on expanding special distribution centers in the Batlic. This came with new challenges, long hours, and new fears of detection.

Sweden — a neutral nation in the war — became the converging ground for intelligence services. Stockholm, known as the “City of Spies” or “Casablanca of the North,” brought in couriers carrying messages, double agents, and everything else in the gamut of espionage. Nowak journeyed alone for 24 days from Warsaw to the Polish port city of Gdynia and then to Stockholm.

Stockholm, known as the “City of Spies” or “Casablanca of the North,” brought in couriers carrying messages, double agents, and everything else in the gamut of espionage.

Aboard a boat, Nowak hid for 80 to 90 hours in a muddy bin of coal whose contents could only be extracted by crane (this allowed him to go undetected by Gestapo search parties and customs police dogs). Once he arrived in Sweden, he linked up with a cell called “Zaloga,” which was headquartered in Warsaw and acted as the in-between with London. The way underground cells communicated, aside from coded wireless messages, was through laison by couriers. Couriers had different callsigns from their fake names to add another layer of security; Nowak’s was “Zych.”

On his trips, Nowak carried “mail” in microfilm stashed in a door key, a figure of St. Anthony, and a cigarette holder. Across Sweden, he began distributing “German underground pamphlets” to German U-boats and Swedish sailors, but most importantly, and under instruction from the Home Army, he delivered the “mail” (plans for a subversive propaganda campaign with the British Special Operations Executive) to London.

Through these journeys, ordinary citizens became Nowak’s lifeline. Contacts were vetted predominately through word-of-mouth. The police force couldn’t be trusted. The best practice, whether as a courier or as a spy, was to act as an invisible man. If their identity documents listed them as a “workman,” then wearing a worn-out jacket, dirty pants, old boots, and a cheap watch strengthened their authenticity.

It took several days for news and messages to travel, and many couriers weren’t aware that trouble was in their future. The Gestapo caught two couriers carrying two sets of photographs of Jan Kwiatkowski (Nowak). The Gestapo now had the face and false name of an important figure that the Polish Underground was trying to extract from Sweden. Always one step ahead of his pursuers, Nowak adopted a new name, which he would use for the rest of his life.

Emissary or Diplomatic Mediator?

Poland’s two top leaders were killed during the historic pitfalls of “Black Week” from June 30 to the early days of July 1943. Stefan “Grot” Rowecki, the commander of the Home Army, was arrested by the Gestapo and assassinated from an order issued by SS Heinrich Himmler. Wdladyslaw Sikorski, the prime minister and commander-in-chief of Poland, died in a plane crash over Gibraltar. Following these events, new leadership — who were still in their Polish government-in-exile in London — took over, and Nowak acted as an emissary.

“As an emissary, I was rather a witness, an eye-witness of the game between Moscow, London, Washington, and I saw the moon from both sides from the perspective of London and Warsaw,” he told the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “But I can’t say that I really influenced any decisions or events.”

Many of these meetings, news radio broadcasts in London, and newspapers were influenced by political ploys, whether it be Soviet propaganda, censorship of the press, or for personal gain. The Allies in the west supported Poland’s efforts for independence, but the Soviets and Stalin ultimately had the leverage to do what they wanted during the “Big Three” meeting in Tehran.

The Soviet Union’s relations with Poland were broken after the Katyn Massacre. On April 13, 1943, 4,443 corpses of Polish military officers were discovered by the Germans. Investigators determined that the soldiers had been killed in 1940 by the Soviets. Thus, Poland severed ties with what they referred to as the “ally of our allies.”

Nowak participated in several historical moments. He met with Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden and discussed cooperation in operations between the Polish Underground and British Special Operations Executive (SOE); he personally met with Winston Churchill to deliver a physical copy of an Action N pamphlet titled Der grösste Lügner der Wett (“The Greatest Liar in the World”), which Churchill vowed to send to the Imperial War Museum; he was a part of a four-man team that flew captured parts of the Germans’ V-2 rocket during Operation Wildhorn III, which provided intelligence to be deciphered by the Allies; and he brought the first news of Nazi atrocities at the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising to London.

When the Rising kicked off at 5 AM on Tuesday, Aug. 1, 1944, it was the first time Nowak saw soldiers of the Home Army openly carrying weapons.

He also became a parachutist, as did many emissaries and couriers. Although he never jumped during a mission, he learned a new way to smuggle microfilm. On one of his training jumps, Nowak broke his arm on a hard landing. He was hospitalized, put in a sling, and his arm cast in plaster. Later, his wife, Jadwiga Wolska (“Greta”), and him would cast their own arms with plaster to smuggle out microfilm documenting the events of the Warsaw Uprising.

Warsaw Uprising

For two years leading up to the Warsaw Uprising (or Rising for short), Tadeusz Żenczykowski, the chief of propaganda (head of Action N), prepared for the large-scale effort codenamed “Rój,” meaning “The Hive”. He included photojournalists, a public address system, a newspaper, a radio station (called Lightning, which Nowak had established), songs with pro-resistance lyrics, a theater, public speakers, writers, poets, and a film unit. The BBC later said of the Lightning broadcast: “This was the first and only time during this war that a broadcasting station had beamed programs directly from the battlefield in an occupied country.”

When the Rising kicked off at 5 AM on Tuesday, Aug. 1, 1944, it was the first time Nowak saw soldiers of the Home Army openly carrying weapons. They wore red armbands — some had eagles on them, and all bore the letters “WP” (Wojsko Polskie/Polish forces). German tanks filled the side streets, and bottles that contained petrol were lit and chucked down from windows on top of them. The crews that escaped were shot. The Polish Underground force was in the midst of urban warfare. One street called Jerozolimskie Avenue grew too dangerous to travel as snipers often killed couriers, liason girls, and anyone not wearing a German uniform.

German artillery, particularly their superweapon Karl-Gerät, transformed eight-story buildings into rubble. One mortar shell that hit the building in which Nowak, his wife, and a few Polish Underground members stayed passed straight through six floors, but didn’t explode. They referred to the shells as the “flying coffin,” and explosive experts later came in to empty it to make homemade hand grenades. The artillery and reinforcement of German infantry forced the Polish Underground to go, literally, underground.

Young scouts under the assumed name “The Grey Ranks” (Szare Szeregi) carried out small sabotage. These activities were nonviolent, usually consisting of teenagers with boyish characteristics painting walls with symbols of the resistance. The most common symbols were anchors or the letter “V” for victory. Sometimes they threw rocks through windows of known German collaborators, raised Polish flags in place of German ones, or slashed the tires of Gestapo vehicles.

Alongside the Grey Ranks were the “Union of Clovers” (Związek Koniczyn), or Girl Guides. These young girls were similar in age to the Gray Ranks, and they identified suspected sympathizers, cared for Jewish people in hiding, rescued wounded children, and served in liaison roles. Greta — whom Nowak later married in a bombed-out church on the 37th day of the Warsaw Uprising a mere 300 yards from the German front — served as a liason girl with the Home Army. She recruited families to establish safe houses for parachutists and couriers.

These girls helped guide couriers carrying reports and insurgents transporting weapons and ammunition, brought food for civilians, and evacuated the wounded to safety using underground highways or sewers. “In those last week’s of Warsaw’s agony,” Nowak writes, “this was the most important and most heroic service of the insurgents.”

Courageous as the effort was, without Allied support, it resulted in capitulation due to lack of food. Those who didn’t flee were deported or killed after the surrender in Warsaw, and the city was destroyed. This disaster resulted in the pro-Soviet Polish government taking power instead of the Polish government-in-exile in London.

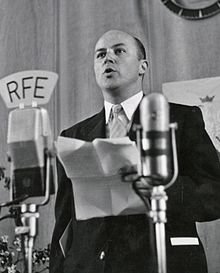

Radio Free Europe

“For 25 years, he was a dominant voice at Radio Free Europe, that great beacon of hope that brought so many through the darkest hours of communism,” said President Bill Clinton while awarding Nowak the Presidential Medal of Freedom. From 1951 to 1976, Nowak ran the Polish Service section of Radio Free Europe in Munich, Germany, and, because there was no underground movement post-World War II, his influence carried behind the Iron Curtain. His voice was a vehicle for information.

“I believed that I had a very good knowledge of people, of mood, of the situation,” he told the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Therefore, I could build the program in such manner that it is best tuned to the mentality, interests, traditions of the Polish audience. Something I could not do in the BBC. In the BBC, British were deciding what to broadcast and how. Here, Americans gave us considerable editorial autonomy. They believed that only free Poles know how to broadcast to their compatriots. Therefore, I could use my knowledge of the audience to make broadcasts as effective as possible.”

The role of Radio Free Europe was to allow people to make their own conclusions with an unbiased view. Covertly funded by the CIA, news during the Cold War wasn’t steered or censored, which erased the aspect of brainwashing and the spread of communism. In fact, Nowak took ownership in fighting hatred and prejudice, and stated his time spent on the radio was the most important of his career.

Nowak served as a consultant to the National Security Council under George H.W. Bush’s administration, became a U.S. citizen, and advocated for Poland to join NATO. Nowak died in 2005; he was 91 years old.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.