Illustration by Kenna Milaski/Coffee or Die Magazine.

The enemy fire was withering, pinning down the small team of Green Berets under a scorching desert heat. Hemmed in from all sides, the team took its first casualty as the desert sun meandered over the horizon. Nightfall brought reprieve from the heat and enemy contact. As light crept over morning, my dad held his blood-soaked teammate in his arms as he took his last breath. They escaped and evaded across the desert while the last shred of darkness covered the earth, the trek made longer by the weight of loss.

I picked up pieces of the story as a child but always longed for more. Clutching my G.I. Joe figures tightly, I would strain my eyes to my dad’s face, hoping to catch one more shred. I wanted to know. I needed to know. But he would gaze off into the distance and coolly say, “That is a story we can share over a beer someday, son.”

I hoped that I would someday earn that beer from him, and so much more. But he was a complicated man, and childhood was a painful and confusing affair both with and without him.

As an 11-year-old, I watched my father pack up every belonging of worth in our foreclosing California mansion and leave. He cleared out every bank account and left my mother, brother, sister, and me with materially nothing.

While loading his U-Haul, he paused long enough to walk over to me and deliver an edict. My feet were glued to the porch, my eyes following his moves in horror and confusion. I wanted to run but couldn’t. With a haunting clarity, he got nose to nose with me and asserted his truth — “I am going to financially destroy your mother” — and then casually returned to his task.

I understood. Unshackled from the cement, I watched my feet enter the house, my hands steal two of his pistols, and my body return to the porch. My heartbeat filled my eardrums as I hoped to pull off the heist that would enable me to protect my mother. He didn’t notice the guns missing from his pile of firearms, and the U-Haul sputtered off into the distance.

The next seven years were difficult, but we made it.

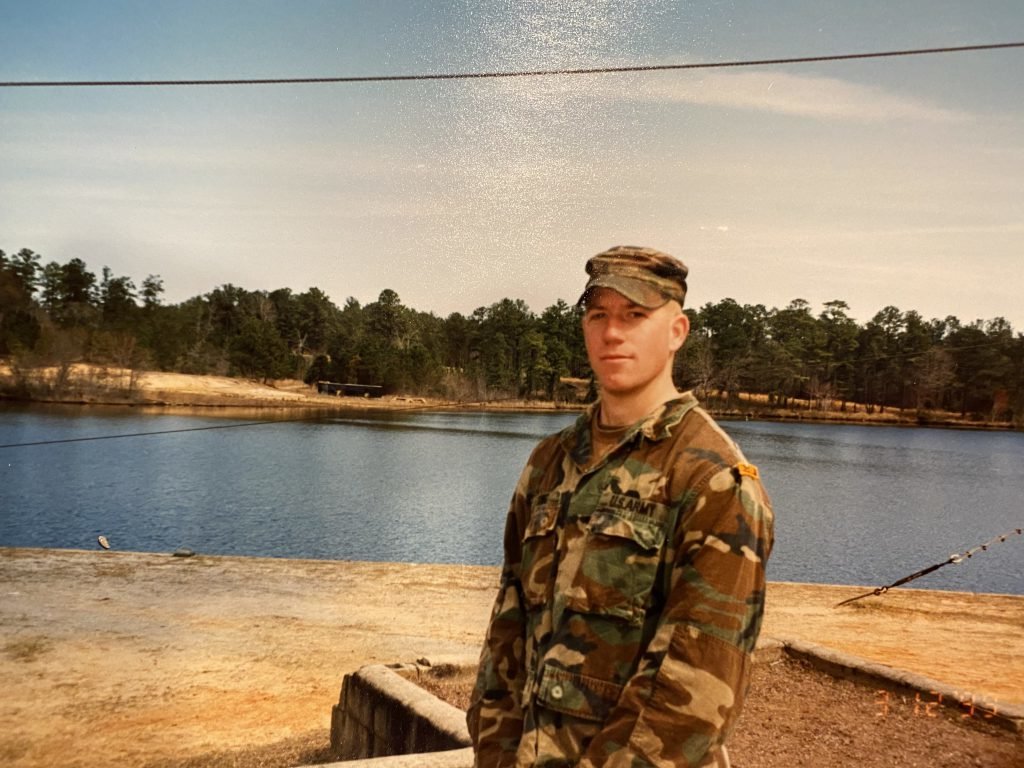

At 18, after arriving at the 2nd Ranger Battalion, I wanted to find out for myself just what I thought of the man who had “financially destroyed” my mother. The man who authored my truncated childhood and so many abuses when he was around. The Army afforded us some common ground to have a relationship, so I started there. The uniform connected us. We had both worn the colors of our nation, both joined the Army at 18 years old, both followed in our father’s footsteps. To me, the uniform represented more than service to our country — it was a bridge to the man I never knew.

It’s a terrible thing to not know your father. You always feel somehow “less,” lacking in some way that only amplifies that hole we all have in our hearts that can only be filled by God. When a parent walks out on you as a child, it feels like the world is conspiring to pity you. It feels like everyone knows you weren’t worthy enough to stick around for.

Through phone calls and emails, I spent time trying to get to know my dad. I learned that my grandfather was one of the original Darby’s Rangers and beamed with pride. I sewed a World War II Rangers Diamond on the inside of my patrol cap as my “drive on” patch, motivating me in the tough times. He died before I was born, and I had only known him as the man who broke his back jumping into D-Day. It felt like I was connected to him, too, through this uniform. I would imagine him jumping out of airplanes with me in Airborne School. Somehow exiting that aircraft felt like entering my unknown heritage.

When I graduated from Ranger School at 20, I asked my dad to come out and pin the coveted black-and-gold tab to my uniform. It was a huge day, a moment that I had earned through suffering and shared with my dad through grace. Hours later, with gaunt cheeks and bellies full of burger, we sat in the afterglow of my accomplishment. Two thieves sharing beers and pleasantries: I had stolen his guns, he had stolen my childhood.

It was time for the real conversation to begin, and I invited him to share, soldier to soldier.

With every question I asked, each answer became harder to receive. It was painful. Not because of the horror of losing a fallen comrade, the fear of imminent death, or the anguish of evading enemy pursuit in the world’s most punishing terrain.

It hurt because it wasn’t true. My dad was a Green Beret — until he wasn’t. My childhood wasn’t the only thing he had stolen. He had also stolen valor. My beer grew warm as my gaze grew cold.

Stolen valor is wrong. So is mockery and defamation. No one wins, especially those that stoop.

Bruce was an Army personnel clerk in Bad Kreuznach, Germany, in the ’60s who took bribes to replace soldiers’ names on deployment rosters to Vietnam. He profited off sending men to their prospective, and in some cases eventual, deaths. He profaned the fraternity of soldiering with his greed. My grandfather was a communications specialist in San Antonio, Texas, during World War II. The two men shared alcoholism along with their uniforms.

Stolen valor has a cost, and as every soldier knows, we all eventually pay for our actions at some point. I paid the price with humiliation. But his cost was far greater.

I had always sought to fill in the gaps, to understand why — or who? But you cannot get to know a man who doesn’t even know himself.

He was twisted from an early age, abused by an alcoholic father. A truly sick man and a social predator. These facts once angered me, but now just sadden me. I am reminded of this every time the most recent case of stolen valor occupies my news feed. Every time I sit next to someone on a plane who tells me they did “Black Ops” that are still classified. Every time I watch the rolling stream of legitimate veterans harassing an imposter on social media.

Stolen valor is wrong. So is mockery and defamation. No one wins, especially those that stoop.

If you earned your stripes, there is no need to validate a liar with a shred of attention. Nor is there much good in trying to intimidate them into change. If you haven’t learned this yet in life, let me help you understand a truth: You cannot intimidate evil or embarrass someone out of their mental health issues. And take it from me, the way the story ends is far worse than the five minutes of fame you give them on social media.

In 2010, I stood over my dad’s intubated body as he was taking his final breaths. It’s a surreal thing watching your parents pass, regardless of whether a relationship is intact or not. It’s sobering when you realize that not a single person in that room hoped he would pull through.

The night before, his wife and her small family that traveled to be with her toasted my dad, the “Vietnam veteran riddled with Agent Orange-induced leukemia.” My siblings and I appreciated their kind gesture and let it pass. They were so genuine, though the man they toasted was not.

But the following morning in the hospital, the real conversation occurred. Sitting face to face with the woman my dad left us for, we listened as she frantically told of him cheating her and saddling her with debt. She spoke of his criminal activities over the years and the uncertainty of how she would pay for the hospital bills. She lamented as to why the VA wasn’t helping pay for his treatment.

We had seen this story play out once before, so I spoke compassionately, explaining that he had never served in Vietnam, was never a Green Beret, and never pitched for the Pittsburgh Pirates, among the list of stories he would tell.

Silently, understanding fell over her. The VA would not be helping with his hospital stay, and now she understood why. We sat for a time, and when she spoke, she apologized, and we accepted. She was not his first victim. She was, however, his last.

As our time was coming to a close, she asked us to weigh in on the “do not resuscitate” order. Though we didn’t feel we owned any part of that decision, we obliged.

Of the handful of memorable statements my father made over the years, two came back to me in that moment, so I shared them as we moved to closure.

“Don’t chase ghosts, because you won’t find them” — that was for me. And, “Promise me, if I’m ever lying on my deathbed in a hospital, pull the plug” — that was for her.

Back in the hospital room, I stood over the dying man, and recognized that he was completely and painfully alone. I doubt he ever knew who he truly was, and he ran from whatever pain he sustained in his youth his entire life. He wanted to be somebody. I suppose we all do deep down. Some of us pursue accomplishments the hard way and own it; others try to rent it or steal it. I would never understand why, but I understood it was time to let it go.

Fumbling with a borrowed Bible for the first time in my life, the word of God found me right where I was. I read Romans 12:19 over him, unfamiliar words of forgiveness to a sad man dying in the weight of the consequences of his actions.

“Do not take revenge, my dear friends, but leave room for God’s wrath, for it is written: ‘It is mine to avenge; I will repay,’ says the Lord.”

Awkwardly, I released the man of all he had ever done to me and walked away.

Lies have a cost. And the truth always comes out in the wash. Pain has a way of being generational — unless you decide to reject your inheritance and build a new legacy for your own children.

When I see those sad people out there trying to steal their worth, I wonder how much pain they have inherited. I wonder how much they hurt inside and if they have ever felt belonging, acceptance, or love. I wonder if they know that it’s okay to be a personnel clerk, serving your country with honor. Sometimes I wish that would be enough for them, as it was for all of the rest of the soldiers they helped. But it’s never enough when you’re chasing ghosts or running from shadows. And none of us can beat that out of someone who is already beaten down by their demons.

I pray that we may remember that the next time we see a mocker foolishly trying to steal their worth. I pray that we may recognize it has nothing to do with us or the fabric they flaunt.

We earned it; they will get theirs.

Brandon Young is a former US Army Ranger and co-founder/principal at Applied Leadership Partners, helping leaders create tightly knit, high-performing teams through executive coaching, speaking, and workshops. He has spent more than 20 years building and leading teams in the military, corporate healthcare, and nonprofit sectors. He’s been published in various peer-reviewed academic journals for his work as a co-developer of the Enriched Life Scale and is currently pursuing a Masters of Divinity in Leadership at Denver Seminary (2023). His passion is faith, family, community, people, and family adventures!

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.