The visit of King George VI to No. 617 Squadron (the Dambusters), Royal Air Force, Scampton, Lincolnshire, May 27, 1943. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The first of 19 modified Lancaster heavy bombers lifted off the runway just after dark on May 16, 1943. The targets were three seemingly impregnable dams in the Ruhr valley of Nazi Germany’s industrial epicenter. Allied war planners expected the destruction of the hydroelectric reservoirs would cause massive flooding, disrupting life in the heart of Hitler’s war machine, slowing or even stopping the production of armor, aircraft, and ammunition to the front lines. Operation Chastise was the official name of the years-in-the-making precision-strike mission against Germany’s production chain, but the aircrew members who pulled it off would forever be known as the “Dambusters.”

Several weeks before the mission launched, the Royal Air Force’s Squadron X, later renamed 617 Squadron, formed under 24-year-old Wing Commander Guy Gibson. The squadron assembled aircrews from Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the US. They trained extensively in intensive low-level night flying and navigation. In the era before night-vision goggles, terrain-following radar, or GPS navigation, flying a bombing run at night at nap-of-the-earth altitude — just 100 feet or less from the ground — was viewed as nearly suicidal.

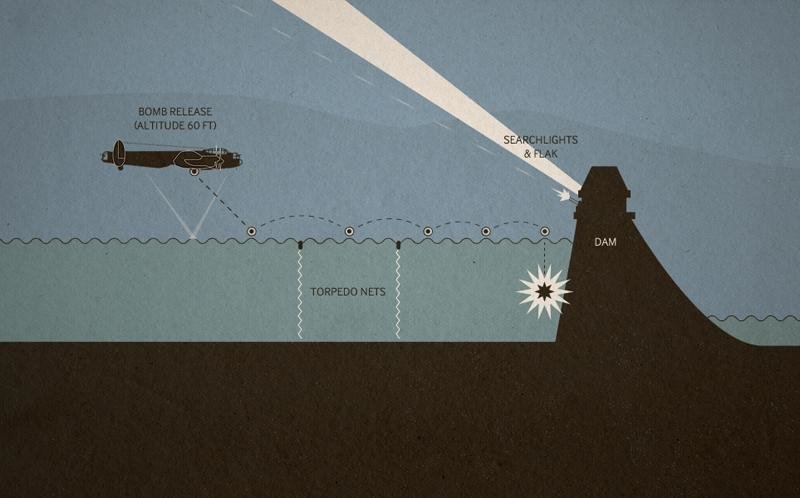

Adding to the mission’s complexity, the Möhne, Eder, and Sorpe dam targets were perceived as impenetrable, guarded with anti-torpedo nets to stop underwater attacks and anti-aircraft guns to prevent aerial assaults.

But these bombers had a secret weapon, one of which was so unbelievable at the time that Sir Arthur “Bomber” Harris, who was in charge of RAF Bomber Command, didn’t even think the weapon would work. “I didn’t believe a word you said when you came to see me,” he told British engineer Barnes Wallis the day after the raid. “But now you could sell me a pink elephant.”

Wallis based the groundbreaking weapon on an idea he had while bouncing marbles across a tub of water in his backyard garden — a “eureka” moment that, understandably, would leave Harris with doubts about the project. Code-named Upkeep, the drum-shaped, purpose-built “bouncing bombs” were to skip across the water, an innovation that avoided both of the Germans’ two layers of defense.

The first layer was anti-aircraft guns, which made flying over the dam, or even approaching it from normal bombing altitude, a suicide mission. But while the guns protected airspace above the dam, their mounted positions did not allow them to shoot directly over the water behind the dam.

In theory then, a torpedo attack might work, if bombers came in over the water, below the gunfire. The bombers could fly low — below 100 feet — and release torpedoes that would race to the dam through the water.

The Germans had strung huge nets in the water to stop that tactic.

But the skipping bombs, released at the same point as a torpedo, would skip over the nets.

The pilots perfected the technique of flying as low as 60 feet and dropping Upkeep bombs over test sites at a ground speed of 232 mph. The bouncing bombs would hit the water with a backspin and skip several times before sinking and detonating near the wall. Once the pilots mastered the technique, the mission went forward.

Gibson’s Lancaster was part of the first of three attack waves. Each of the 19 four-engined airplanes carried a single Upkeep bomb, so the aircrews had to be precise. Gibson’s initial approach around midnight on May 17 was a dummy run to mark the defenses of Möhne. He came around for a second pass to unleash his Upkeep, but it fell too short. The next pilot came in, but enemy flak hit the plane, forcing the aircrew to drop their Upkeep late. The bomb bounced over the dam. Two of the aircrew bailed out before the aircraft exploded. In the third plane’s attack, the Upkeep veered left, exploding 20 yards from the dam. The fourth plane’s bomb bounced three times and detonated against the dam, ripping a hole in the structure. A second direct hit widened it.

The remaining aircraft that hadn’t unleashed their bombs, plus two that had, flew to Eder and successfully breached the wall of its dam at 1:52 a.m. However, the Sorpe dam, though damaged during two attack waves, remained intact.

Aircrews had more to fear than enemy anti-aircraft fire. At least one of the planes collided with power lines because it was flying so low. Another bomber accidentally skimmed across the water, which tore off the bomb carried on the aircraft’s belly.

Of the original 133 Allied aircrew members, 53 were killed in action, and three more were taken prisoner. But the results of the Dambusters’ mission were catastrophic for the Germans as the shattered dams released 330 million tons of water into the Ruhr region.

“I saw the face of one of the Lancaster pilots as he made a turn overhead,” Josef Rochel, who was 13 at the time of the bombing, recalled. “They were flying incredibly low, and we all knew what they were after — there was nothing else in Günne apart from the dam. My father had built an air-raid bunker in the woods and we ran to it but then had to go back to get the goat and pigs out of the cellar. My father shouted, ‘They’ve got the dam!’ None of us could believe it.”

The flooding killed at least 1,600 civilians, prisoners of war, and Polish, Ukrainian, and Russian slave laborers. Four weeks before the raid, Nazi Armaments Minister Albert Speer had proposed to Hitler forming a committee of industrial specialists to identify crucial targets in Soviet power production. Instead, his resources ended up temporarily focused on repairing the dams. The Dambusters raid proved to be successful, momentarily halting Hitler’s supply production and serving as a major morale boost for the Allies.

The aircrew members’ heroism was celebrated in a 1955 motion picture. The Dam Busters sits at 100% on Rotten Tomatoes and was nominated for an Oscar for best special effects. Today, there is only one surviving member of the Dambusters: bomb-aimer George ‘Johnny’ Johnson, 99.

Read Next: A Star on the CIA’s Memorial Wall: Chiyoki ‘Chick’ Ikeda

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.