8 Fascinating Stories Surrounding D-Day You Probably Didn’t Know About

On the 75th anniversary of D-Day, we remember the stories of those who contributed to the largest seaborne invasion in history on June 6, 1944. Most people are familiar with the story — movies have been made about the epic invasion since a few years after it happened. But we wanted to highlight the obscure and lesser-known contributions to the cataclysmic event. The efforts that worked in secret to bring D-Day to action, the soldiers who braved insurmountable odds against a defiant enemy, reporters and photographers who documented the day that so many recollect, the resistance groups that waited to strike, and the deception that crippled morale in frontline soldiers and enticed civilian cooperation.

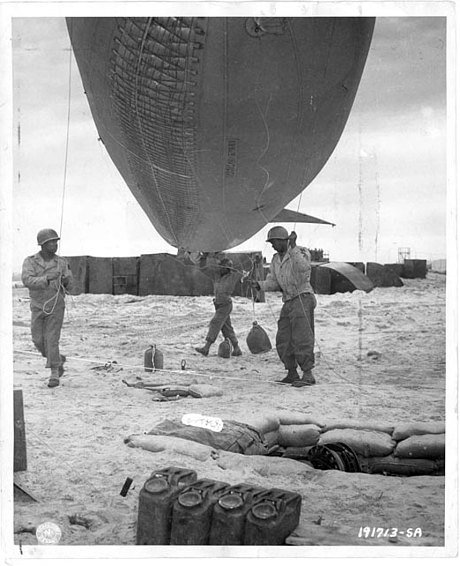

8. 320th VLA Barrage Balloon Battalion

The 320th Very Low Altitude (VLA) Barrage Balloon Battalion was the only all-black combat unit to land on Omaha and Utah beaches. They arrived with the third wave, and their task was to provide protection from the air by hovering above the beachhead like a canopy to prevent German aircraft from strafing the ground troops and ships. “Once deployed the balloons had steel cables hanging down from them, which would neatly slice off an airplane’s wing if it hit the cables at 300 or 400 miles per hour,” said Jonathan Bernstein, the director of the Army Air Defense Artillery Museum. “The 320th Battalion did actually score a confirmed ‘kill’ by cutting off the wing of a Junkers Ju-88 over Omaha Beach on D-Day.”

Long-range German artillery could make out their impression from several miles away from their inland positions and fired at the ships they were tethered to. Despite the threat from the Luftwaffe being minimal, the several hundred balloons that roamed the skies after the beaches were secured aided in the invasion.

The most notable member of the unit was Waverly B. “Woody” Woodson Jr., recommended for the Medal of Honor for his actions as a medic on Omaha Beach. Woodson, aboard a landing craft tank (LCT), braved artillery fire as they neared the coastline. “They were shelling the devil out of us. At the same time, we went over two submerged mines. The whole thing jumped out of the water,” he remembered.

Shrapnel ripped through his buttocks and thigh, but he managed to reach the shore following a tank and set up a trauma station under the cover of a rocky ridge, where an estimated 200 wounded received his care. Linda Hervieux wrote in her book “Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day’s Black Heroes, At Home and At War,” “He pulled out bullets, patched gaping wounds, and dispensed blood plasma. He amputated a right foot. When he thought he could do no more, he resuscitated four drowning men. Thirty hours after he set his boots on Omaha Beach, Woody Woodson collapsed.” Woodson died on Aug. 12, 2005, an undisputed hero of the 320th.

7. Martha Gellhorn: The First Woman to Cover D-Day

When you’re a reporter who just got denied access to the would-be largest military invasion in history, the only logical thing next step is to sneak onto a hospital ship and lock yourself in the bathroom while sitting on the toilet. This is precisely what Martha Gellhorn did as the first female reporter to document the events of D-Day. She disguised herself as a stretcher-bearer, waded into the waist-deep water, helped the wounded in tents set up on the secured beach, and wrote about what she saw — not the statistics.

“Cigarettes had to be lighted and held for those who couldn’t use their hands. It seemed to take hours to pour hot coffee via the spout of a teapot into a mouth just showing through bandages,” she wrote of her D-Day experience.

Her primary focus was on the human toll war takes, particularly on the average soldier and the civilians that carry the obvious and hidden wounds. “In terms of life, the price falls most heavily where it is least deserved and least noticed — on children.”

She disguised herself as a stretcher-bearer, waded into the waist-deep water, helped the wounded in tents set up on the secured beach, and wrote about what she saw — not the statistics.

And yet, after confidently proving herself as a reporter, some downplay her legacy to her brief marriage to Ernest Hemingway. She rejected that notion, saying, “I was a writer before I met him, and I have been a writer for 45 years since. Why should I be a footnote in someone else’s life?”

Gellhorn would go on to cover the Vietnam War, the Six-Day War in the Middle East, murders in El Salvador, collateral damage during the Invasion of Panama, and so much more during her 60-year journalism career. Her lens of covering conflict on the field rather than on the sidelines made the reader feel the experience.

6. The Dames of D-Day

Although Martha Gellhorn served as a trailblazer for female journalists and war correspondents, others deserve equal merit for their efforts to act as the eyes of millions in order to get a glimpse of the war unfolding thousands of miles away. These women were affectionately called the Dames of D-Day or the D-Day Dames.

Helen Kirkpatrick, like many of her female colleagues, was shunned for her audacity to carry out a man’s job. The Chicago Daily News would only allow male reporters to contribute to their magazine, but there was one exception — the word “no” wasn’t in her vocabulary. “I can’t change my sex. But you can change your policy,” Kirkpatrick said. On her first assignment in London, she sought to interview the Duke of Windsor, an impossible proposition considering the king didn’t do interviews. To the amazement of her male counterparts, the headline she submitted read, “Duke of Windsor’s interview with Helen Kirkpatrick” — the king interviewed her.

“I can’t change my sex. But you can change your policy.”

She covered the London Blitz, spent half of 1943 covering North African campaigns in Algiers, braved sniper fire at the Cathedral of Notre Dame, and once stole a frying pan from Hitler’s Bavarian hideaway, commonly referred to as the “Eagle’s Nest.”

Like the men of Easy Company of the 101st Airborne Division, lounging sipping on a cold drink on the patio of Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest, another D-Day Dame, Lee Miller, also took advantage by posing for a once-in-a-lifetime photo-op — completely naked in Hitler’s bathtub. That same day, Allied forces marched through Munich and liberated the city of the Third Reich.

Miller’s previous career as a model provided experience in capturing emotions in a photograph, both in understanding the subject’s perspective and how to manipulate a camera. Her unforgettable images showed the wrath of the Nazis, a lasting impression that haunted her until her final days.

5. The Giants of Sword Beach

“I wish you all the best of luck of what lies ahead,” Brigadier Simon “Shimi” Fraser, Lord Lovat of 1st Special Service Brigade, told his men on the eve of D-Day. “This will be the greatest military venture of all time; the Commando Brigade has an important role to play and 100 years from now your children’s children will say, ‘They must’ve been giants in those days.’”

Their mission was to race through a hail of gunfire along the eastern part of Sword Beach and 4 miles inland to provide reinforcements to the 6th Airborne Division along the Caen Canal. Alongside Shimi was his trusted piper, Private Bill Millin. Bagpipes were famously used to boost morale during World War I but were easy targets and many of them died. A policy was enacted to protect them from marching alongside troops in direct combat.

Naturally, Shimi convinced Millin to go against policy when he told him, “Ah, but that’s the English War Office. You and I are both Scottish, and that doesn’t apply.” The pair were the first to hit the sandy beach; immediately, Shimi ordered Millin to play “Highland Laddie.”

Millin told the BBC, “I didn’t notice I was being shot at. When you’re young, you do things you wouldn’t dream of doing when you’re older.”

“Wounded men were shocked to see me. They had expected to see a doctor or some kind of medical help. Instead, they saw me in my kilt and playing the bagpipes. It was horrifying, as I felt so helpless,” recalled Millin. He saw the chaos of war as his own armored tank ran over wounded Allied soldiers, killing them as they lay wounded off a beaten road.

A captured German sniper later remembered watching Millin marching back and forth on the beachhead playing his pipes. They thought he had lost his mind and aimed their sights on those who had weapons instead of instruments. Millin told the BBC, “I didn’t notice I was being shot at. When you’re young, you do things you wouldn’t dream of doing when you’re older.”

The Giants of Sword Beach prevailed and marched to relieve the British army unit that had secured the bridge. Shimi’s response to arriving at the rendezvous just after 1 PM: an apology for being two minutes late.

4. The Parachutin’ Padre

Amongst the 13,348 U.S. Army paratroopers jumping into Normandy, only 13 were chaplains. One of them was Father Francis L. Sampson, who would go on to earn the Distinguished Service Cross, the Bronze Star, and the Purple Heart medals. He later wrote of his experience jumping into Normandy, “It will always remain a mystery to me how any of us lived. I collapsed part of my chute to come down faster. From there on I placed myself into the hands of my guardian angel.”

He nearly drowned when he landed in a swamp and his heavy 120-pound sack containing his combat and religious gear kept him down. He was able to get up for air with the help of a gust of wind and quick thinking with his knife. Sampson heard the screams of bullets zipping around him; he watched a frantic pilot steer a C-47 into a nearby field and disappear into a blast of orange fire and thick, black smoke. He crouched and hurried alone, praying for each of the fallen he passed until he found fellow paratroopers huddled in a grove and joined them.

Sampson worked at an aid station caring for those who had been shot, blown up, burned, and disabled, and giving last rites to those who had passed. The Germans surrounded his position, and one German soldier pointed his pistol into Sampson’s stomach and fired. The bolt clicked, but another German stopped the commotion and spared him after noticing the red cross on Sampson’s left arm and cross around his neck.

“It will always remain a mystery to me how any of us lived.”

He tended to 14 seriously wounded Americans and outlasted a night of a fierce artillery barrage. The four-hour onslaught destroyed the house they were using for shelter. Sampson pulled the trapped men from the collapsed debris and administered aid, including a procedure involving blood plasma.

Later, during the Battle of the Bulge, he jumped into Holland, and the Germans searched at Bastone with roving patrols and captured him. In more than 10 days, they marched 185 miles before they were forced into a train to deliver them to a prison camp.

Come December, Father Sampson was one amongst thousands of American prisoners of war. He led prayer twice a week, which helped boost the spirits of the prisoners. Sampson went on to have a seasoned military career and was promoted to the rank of major general before retiring in 1971.

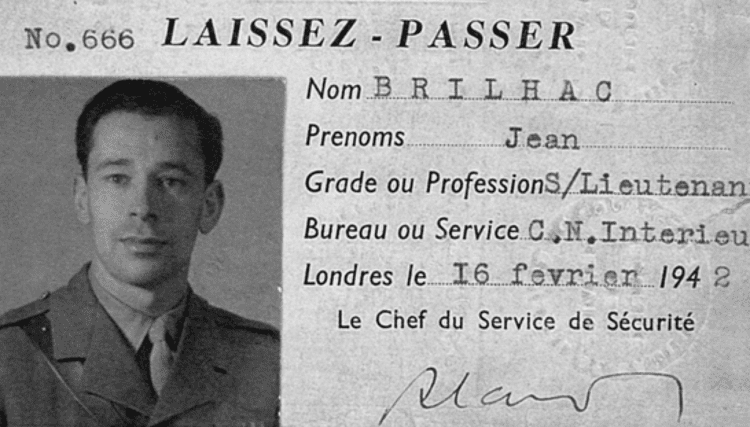

3. “The dice are on the carpet”

Before the Allies launched Operation Overlord on the beaches of Normandy, they needed to warn of their arrival without spoiling the surprise for the Axis powers. BBC’s Jean-Louis Cremieux-Brilhac worked as a secretary for the Free French Propaganda Committee, and he worked alongside four or five others to ensure the safety of its citizens. But they also wanted to aid the Allied effort in any way they could, including “serving as guides to their troops and parachutists; and locating and signaling traps and minefields.”

Other broadcasts targeted resistance groups and Special Operations Executive handlers, which contained secret “personal messages” for the trained ear. They were brief, odd, and humorous, and called for action or cancellation of a mission to sabotage. “Le lapin a bu un apéritif,” in French translates to “the rabbit drank an aperitif.” Another repeated twice over the radio waves translated to “John has a long mustache.”

Bands of Malestroit resistance fighters received orders from the French National Council of Resistance (CNR) pipeline to anticipate daily broadcasts that instructed them to halt the advances of German reinforcements in Brittany, France. From June 4 to June 6, three distinct phrases were sent. “The dice are on the carpet” was the first message to carry out the Green Plan, which targeted strategic railways and trains carrying supplies.

German intelligence listened to the poetry and recognized that it may have been a message, but they couldn’t decipher who it was intended for nor get the warnings to a higher command.

The Violet Plan involved cutting communication lines and cables to confuse the Germans. The final message translated to “it’s hot in Suez,” and it called for the 3,500 volunteers to mobilize under the Red Plan, conducting guerilla warfare missions.

Famously, Paul Verlaine’s line poem Chanson d’Automne — “Les sanglots longs des violons de l’automne” (the long sobs of violins of autumn), followed by “wound my heart in a monotonous languor” — hinted that the invasion was on their doorstep. German intelligence listened to the poetry and recognized that it may have been a message, but they couldn’t decipher who it was intended for nor get the warnings to a higher command.

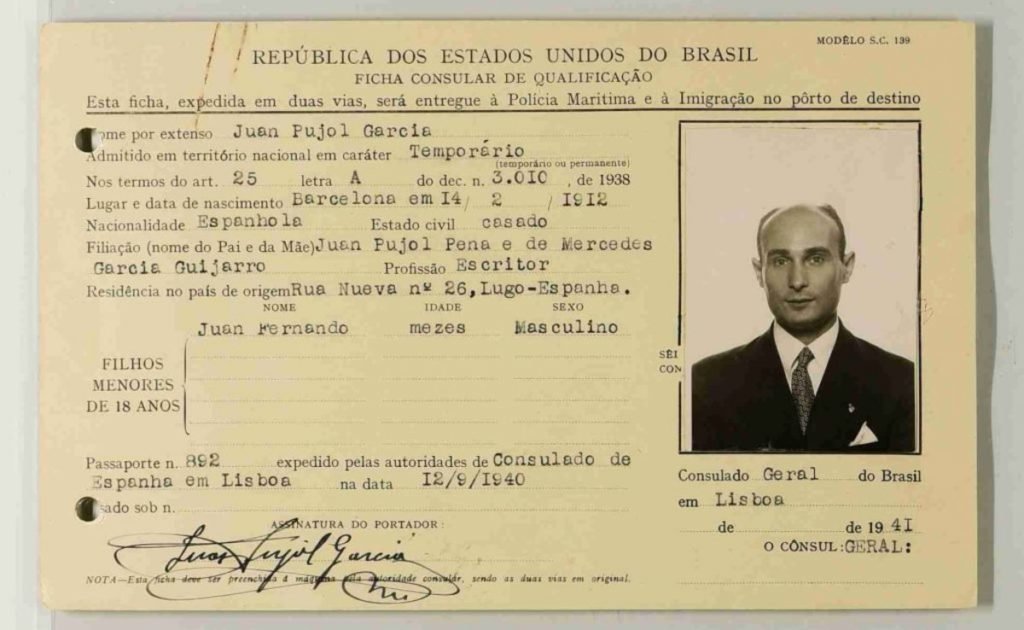

2. CODENAME “Garbo”

When British Intelligence turned down Juan Pujol Garcia for lacking experience and connections, he contacted Nazis from the Third Reich and told them he wanted to spy on the British. It was a ruse in his master plan to earn his spot in the agency as a double agent — without any formal training and by using his imagination as a weapon.

His contacts, all 27 of them, were fabricated to appear as if they were real people with real backgrounds. The information he sent to the Germans about the activity in London was gathered from encyclopedias, advertisements, any and everything at his disposal, despite never setting foot once in the U.K. They never expected him to be a double agent working for the British. This was largely due to his tactics. He purposely sent intelligence late to the Germans, warning of Operation Torch landings in North Africa. He received the response, “We are sorry they arrived too late, but your last reports were magnificent.”

The British labeled him CODENAME “Garbo” after the mystifying actress Greta Garbo. Garbo, using his established network of field agents, transmitted over 500 radio messages to Berlin between January 1944 and D-Day warning of the Operation Overlord plans. When the Normandy invasion was finalized, attention was pushed to convince Hitler the attacks would be occurring at Pas de Calais instead.

He faked his death and moved to Venezuela to escape, before arriving back in Europe to his confused family nearly four decades later.

In order to carry out this massive deception, a ghost army comprised of the fictional First U.S. Army Group (FUSAG) — numbering 150,000 men and led by General S. Patton — was planning to feign an attack on Normandy as a diversionary tactic. The “real” invasion would be occurring in the north. Garbo intentionally sent a warning on June 9, 1944, three days after the invasion, informing the Germans of what was about to occur on D-Day and, because of this, his credibility never wavered. Hitler awarded him the Iron Cross for his extraordinary work, without realizing he was being played.

What happened to the man of mystery that tricked Hitler and the Nazis after the war? He faked his death and moved to Venezuela to escape, before arriving back in Europe to his confused family nearly four decades later.

1. Fake News and Leaflet Propaganda

One of the often forgotten aspects of D-Day was the logistical coordination it took for the Psychological Warfare Division (PWD)/Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), other Allied units, and civilian agencies like the Office of Strategic Services to create hysteria, confusion, and doubt through strategic leaflet campaigns and fake news across Europe.

Prior to D-Day, the Royal Air Force (RAF) and 8th Air Force dropped approximately 2,750,000 leaflets by aircraft. The first newspaper to deliver the news of the D-Day invasion was Nachrichten für die Truppe (News for the Troops). This Allied newspaper, written entirely for German troops (later for civilians) by a skilled and dedicated team of bilingual writers, mixed accurate real-world operations in daily news format with false, unsettling details that members from the High Command were profiteering from the war and living lavish lifestyles. To pull off the deception, the newspaper also included results of sporting events and scantily clad pin-ups.

The “black” leaflets were exclusively distributed by the OSS and PID (a cover name for the Political Warfare Executive) disguised as if it was created by enemy sources. These materials had positive reactions in demoralizing the enemy.

A message from a German commanding officer to a higher command read, “They bring, in part very clever, partly somewhat clumsy form, the news of yesterday. Even the most self-respecting soldier is tempted to read these newsheets, since our own Frontkurier usually does not arrive until the late afternoon or even three to four days later. There must be some way for us to bring the news to our men earlier than the enemy in order to kill the soldier’s curiosity.”

Some newspapers distributed from the “white” angle, where surrender was stressed rather than desertion because Germans felt that was dishonorable. Each paper had a goal and millions of copies were airdropped daily — some were even packed into bombs and fired with artillery.

The results from these propaganda campaigns were deemed effective considering that many German POWs had leaflets in their personal items when they were captured. The lessons used during World War II have had considerable influence in future wars and conflicts.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.