Dear John letters were not exclusive to World War II. Composite by Kenna Lee/Coffee or Die.

Before soldiers could send texts and emails from war zones, long-distance chats were written on postcards and sent in the mail. For Americans serving overseas during wartime, letters from loved ones were a rare reminder of what — and who — was waiting at home. Except when they weren’t.

Sometimes American GIs, expecting love notes from a special Valentine sweetheart, opened their mail and read: “Dear John, Sayonara.”

These so-called Dear John letters became prominent during World War II and a public symbol of “female betrayal” in wartime. Although most letters written to a soldier far from home were cherished, few physical Dear John letters exist today, which should come as no surprise. Honestly, who wants to preserve a heartbreak for the sake of posterity?

Valentine’s Day isn’t always about chocolate and roses for those nursing a broken heart, so what better way to prepare than by looking at the origin of Dear John letters and reminiscing on past romances gone bad?

Love-ly Gear: Stock up on mugs, coffee, and apparel

What’s in a Name: ‘Dear John’?

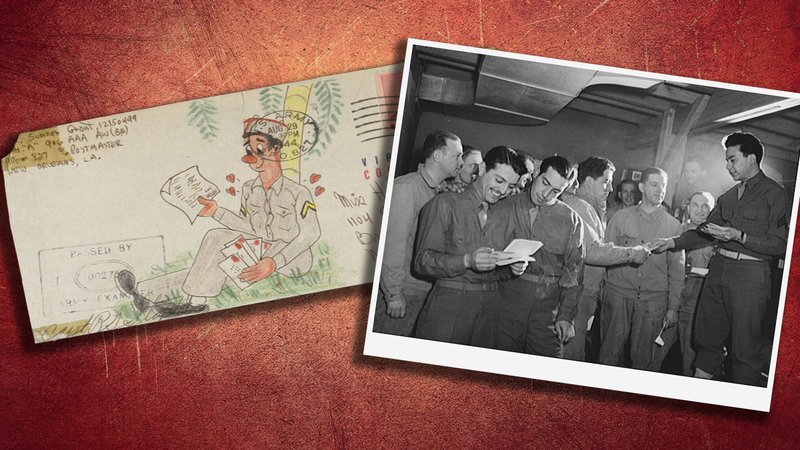

Mail call was an exciting time for most American GIs serving during World War II. Despite the occasional Dear John, not all mail was bad news. Pfc. Sumner Grant sent the illustrated envelope, left, to his fiancée, Helen. Right, soldiers at Fort Belvoir in 1943 receive their mail. Photos courtesy of the Library of Congress. Composite by Matt Fratus/Coffee or Die.

Precisely how Dear John letters got their name is a mystery. However, there are some working theories. According to Susan L. Carruthers, the author of Dear John: Love and Loyalty in Wartime America, Dear John was “a synonym for a breakup note sent by a woman to a man in uniform.”

Carruthers suggests one early inspiration could have been the nationally broadcast radio serial The Irene Rich Show. “This anthology of mini-dramas used the epistolary form as its hook, each episode beginning as though Rich were reading aloud a letter she penned,” Carruthers wrote. “(Hence the show’s alternative name: Dear John.)”

It may be just as simple as that huge numbers of GIs were named John. From 1900 to 1972, John was a top five baby name in American households.

Related: A Commander’s Letter Home to a Worried Mother in 1944 Led to Long-Delayed Silver Star

Who Popularized ‘Dear John’ Letters?

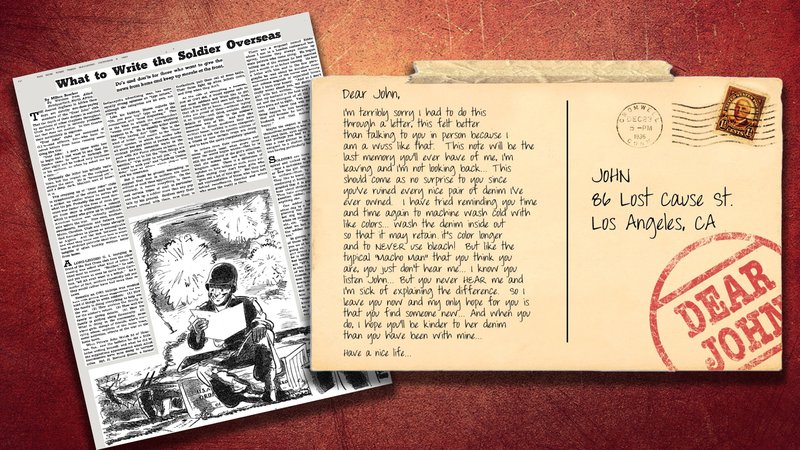

The newspaper clipping of Milton Bracker’s story was published in the New York Times Sunday magazine in October 1943 with the headline, “What to Write the Soldier Overseas.” Composite by Matt Fratus/Coffee or Die.

In October 1943, 24-year-old war correspondent Milton Bracker wired a story for publication from Allied Headquarters in North Africa. His featured headline in the New York Times Sunday magazine read, “What to Write the Soldier Overseas.” According to Carruthers, the news story marked the first time an influential newspaper detailed the Dear John letter phenomenon.

Bracker’s story discussed the prevalence of “Dear John clubs” throughout the Army. These clubs — also called brush-off clubs — were formed by sympathetic GIs and officers for mutual support. Separation from the things they held dear, their families and hometowns, as well as lovers, was nearly unthinkable during peacetime for those growing up with traditional American upbringings.

Bracker provided an example of a letter that a GI might receive, which held a twist:

“Dear John: I don’t know quite how to begin but I just want to say that Joe Doakes came to town on furlough the other night and he looked very handsome in his uniform, so when he asked me for a date—”

Bracker included the name “Joe Doakes” as one many GIs would have recognized in the 1940s. Joe Doakes was the fictional name of an “average guy” featured in a series of short films shown in high schools of the time that taught students basic skills.

Bracker’s fictional Dear John letter, then, might be the origin of the mythical military figure known to generations of soldiers as the hometown rival waiting to steal your sweetie away: “Joe D.”

But Bracker also noted that soldiers would rather receive lousy news than no news at all. Troops would stash letters from home in their footlockers and retrieve them to be read at the mess table. “Their faces light up when letters come,” Bracker wrote, “and drop when they don’t.”

Sweet Gear: Check out BRCC’s Valentine’s Day collection

Dear Jane & Letters Beyond World War II

Deployments often leave soldiers missing loved ones. A soldier of the 1st Brigade Combat Team, 34th Infantry Division, deployed to Camp Arifjan, Kuwait, in support of Operation New Dawn, Oct. 12, 2011, writes a letter home. US Army photo.

Men were not the only unlucky ones. Women serving during World War II and in wars and conflicts thereafter received their own ego-shattering letters, dubbed the “Dear Jane.” Toby Newman, a Women’s Army Corps veteran, told the Library of Congress in 2015 that her loving boyfriend dumped her in this manner. “You wanted to be free, now you’re free,” the Dear Jane letter read. Unlike most of her male peers, Newman never destroyed the note bearing the bad news, even after some seven decades.

The Dear John or Dear Jane letters outlived World War II. In 1953, country musicians Jean Shepard and Ferlin Husky performed a duet of their hit single, “A Dear John Letter.” The song, set amid the Korean War, was so popular that it topped Billboard magazine’s country music charts. In Vietnam, mail calls were sometimes called the “Dear John roundup.” Steven Curtis, a US Marine Corps photographer between 1968 and 1970, recalled witnessing mixed reactions.

According to Curtis, he would counsel other Dear John letter recipients by stating this was a blessing in disguise. “Any woman who didn’t have enough strength of character to stand by her man in his time of need wasn’t worth going back to anyway,” he’d tell them.

After the Vietnam War, handwritten love letters remained common until about the early 1990s. With the arrival of cell phones and smartphones, there was a new preferred method of communication, relegating the Dear John letter to the past.

Read Next: Romeos, Red Sparrows, and the Art of the ‘Honey Trap’

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.