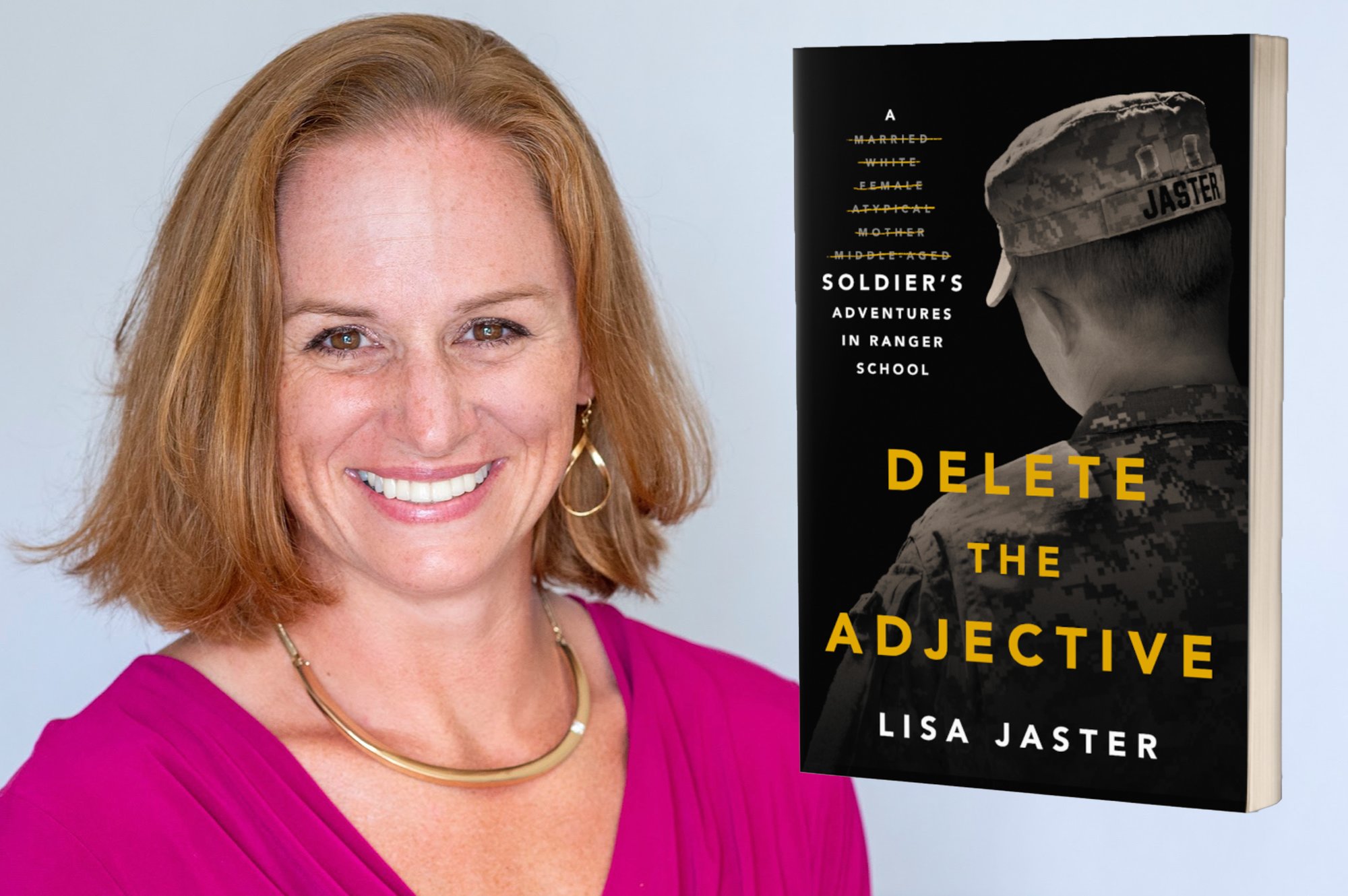

Lisa Jaster's Trailblazing Journey Through War and Ranger School

Lisa Jaster's new book tackles the hardships soldiers endure in the US Army's notoriously difficult Ranger School. Photo courtesy of Lisa Jaster, composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Lisa Jaster joined an elite order of Americans when she graduated from the United States Military Academy with the Class of 2000. From there, she assumed the myriad responsibilities of an Army officer, receiving her commission just as the United States was about to undertake simultaneous wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Jaster, an engineer, led troops on the ground in both theaters. In Afghanistan, she participated in Operation Anaconda — one of the war’s first major engagements. She then took part in the invasion of Iraq and helped build and repair vital infrastructure during the chaotic months after Saddam Hussein was toppled. Years later, in 2015, she made history by becoming one of the first female soldiers to attend the Army’s famously difficult Ranger School. Since then, at least 50 more women have completed the leadership course to earn the coveted Ranger tab.

Now living in Texas, the 44-year-old mother of two devotes her time to raising her children and training in Brazilian jiujitsu while juggling her duties as a lieutenant colonel in the Army Reserves. As if she were not already busy enough, she has just finished writing a memoir, Delete the Adjective, which traces her journey from her small-town upbringing in Wisconsin to her trailblazing military career. Coffee or Die sat down with Jaster to talk about the book and the experiences that shaped her as both a soldier and a person.

US Army Maj. Lisa Jaster stands in formation during the Ranger School graduation on Fort Benning, Gieorgia, Oct. 16, 2015. Jaster is the third female Ranger School graduate. US Army photo by Staff Sgt. Alex Manne.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

COD: After graduating from West Point, you served in Iraq and Afghanistan. What was it like to be a junior officer heading overseas to both wars within the first four years of your career?

LJ: It was very interesting in that, while lieutenants have positional power, it’s really the platoon sergeant who runs your platoon because they’ve got 16-plus years in the Army. They really know what’s going on. I hate to say combat in reference to me because I didn’t see half of what most combat veterans did, but when you’re in what is considered a combat zone, the officers have a very distinct role. I was in a combat heavy engineer battalion, which meant we did minefield clearing operations before there were clearance platoons. Now in the military, minefield clearing is a focus. There are clearance platoons, clearance companies, area clearance, route clearance — we didn’t have any of that in those days, so I had to do it all with my bulldozers. We were also the construction engineers, so I had scrapers and graders and construction equipment.

It could be a blessing and a curse, depending on how you look at it, but I was blessed because I didn’t just have a lieutenant’s knowledge in military construction; I had a degree in civil engineering from the oldest engineering institution in America [West Point]. Being 23 years old in Afghanistan, I knew how to build roads and how to do soil stabilization. Because I was the only degreed engineer on site, and I had that extra knowledge, not only did I have a lieutenant’s obligations, but it allowed me to add value in another way besides just being a platoon leader. I was doing calculations with a pencil because laptops weren’t really a thing yet. Smartphones weren’t a thing yet.

In those early days, IEDs were new, so we didn’t have armored Humvees or any of the mine-resistant equipment. We took one of our D7 bulldozers, added a rake in front, and then put double the metal on it, which turned it into a Mine Clearing Armor Protected dozer. We were still putting sandbags on the bottom of our Humvees and saying, “Hey, just put one foot forward, one foot back, and pray you don’t hit anything.” It was a very different time. I went back to Iraq in 2018, to some of the same bases that I helped build in 2003, and it was insane to see the difference. Even the equipment was just so different.

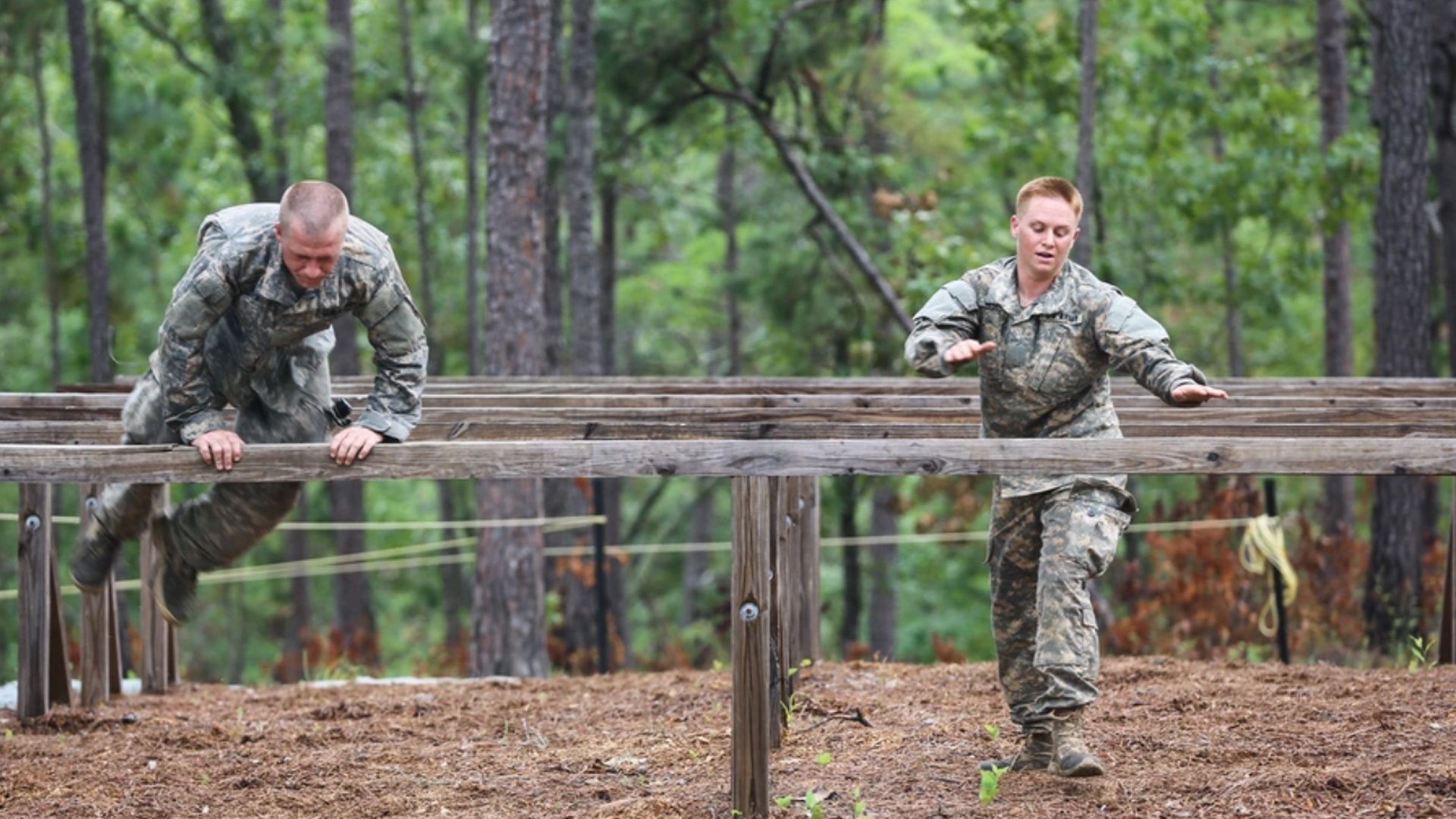

Maj. Lisa Jaster participates in the Darby Queen obstacle course as part of their training at the Ranger Course on Fort Benning, Ga., June 28, 2015. Soldiers attend the Ranger Course to learn additional leadership and small unit technical and tactical skills in a physically and mentally demanding, combat simulated environment. US Army photo by Staff Sgt. Scott Brooks.

COD: Iraq and Afghanistan often get merged together under the broader Global War on Terror umbrella. What was the main difference you noticed serving in those countries?

LJ: Afghanistan has had a more consistent, war-torn nature to it. It is much more tribal, whereas Iraq had a central system. The people hadn’t splintered like in Afghanistan. Being a young officer trying to build relationships with Afghan tribal leaders is very, very different than trying to build relationships with Iraqi government leaders. In Afghanistan, I would attend a dinner with someone who you couldn’t tell him from anyone else in Afghanistan. And then in Iraq, we met with the local nationals — they had positions, they had uniforms, they were identifiable.

COD: In 2015, you joined the first Ranger School class to include women. What was it like to be part of such a historic moment? And what did you find to be the most challenging aspect of the course?

LJ: Our class started in April 2015, with the hope we would graduate in June of 2015. Ultimately, Capt. Kristen Griest, Capt. Shaye Haver, and myself were the only three women who started that first class to graduate. Griest and Haver, of course, graduated two months earlier than me. I was recycled in Florida Phase, the third and final phase of Ranger School.

Nobody recycles Florida. It’s like a 93% pass rate. If you get there, you’re probably going to pass, but I recycled Florida. And right when I recycled, my dad was diagnosed with terminal cancer. We got our mail for the first time in three weeks and I got a letter saying I needed to call my dad because he has cancer. I called him, and he couldn’t talk because part of his jawbone had been removed. That’s when I was like, “Wait a minute. This isn’t like skin cancer. This is serious.”

There were a lot of things that were really trying about Ranger School, but I was prepared for it. Before we started the course, I even said, “They’re going to have to take one female and really, really test her.” Because the last argument against women in combat arms concerns our ability to sustain ourselves in austere environments for extended periods of time. And what better way to test it than to keep one of us at Ranger School for an extended period? I was saying that kind of tongue-in-cheek, but on the flip side, I really believe that as a 37-year-old mother of two who did Army part-time in the Army Reserves I was the perfect person to test. I don’t think there were any conspiracies whatsoever. I don’t think the Army was trying to screw me. I just believe that it was probably a really good test for women staying there longer.

To make it short, I was mentally prepared to be at Ranger School for an extended period of time, so the recycles weren’t nearly as challenging as when I finally did get to Victory Pond and my dad — who graduated from Ranger School in 1968 — couldn’t be there and died several months later.

Jaster continues to serve in the US Army Reserve. Photo courtesy of Lisa Jaster.

COD: I know you first got the idea for the title of your upcoming memoir after hearing your friend say it, but can you explain how “delete the adjective” pertains to your story?

LJ: When I handed off the first few chapters of the book to one of my buddies, he was like, “Oh, yeah, I could tell you that exact same story. It’s a little different coming from you, but not really.” And as I’ve gone through public speaking engagements regarding leadership, integration of women into combat arms, team building, and various related topics, men that attended Ranger School would come up to me after every single engagement and say something to the effect of, “Oh my God, I remember that swamp” or “I remember experiencing that.” After repeatedly getting that same reaction, I thought with all the people who worry that women are infiltrating a man’s world, or we’re reducing the masculinity of combat arms, I wish they could hear these people say exactly what they’re saying to me. My dad’s Ranger School stories from 1968 were almost identical to mine.

I constantly heard about being a female Ranger School graduate, but being a female actually doesn’t differentiate me. It only differentiates me to the people who don’t know, but they’re making a big deal out of the one thing that didn’t matter at Ranger School — the fact that I was female. The only thing that mattered was my ability to hold my own weight, do land navigation, and effectively engage the enemy at the right time. Delete the Adjective seemed appropriate, and I’ve found that to be true in so many aspects of my life. I’ve worked construction and in the oil and gas industry, I’ve worked on offshore rigs. I’ve worked in these all-male environments where I walk in as a 5-foot-4-inch 140-pound female, then about 15 minutes into working with me, nobody cares anymore that I’m a woman. They only care whether or not I can do my job.

We can’t limit our pool of employees — whether it be in the military or in corporate America — based on their adjectives. It’s good to celebrate breaking glass ceilings, but that should be after the completion. I shouldn’t get a headwind just because I’m a female who graduated from a school, but getting a tailwind is a different story.

Maj. Lisa Jaster, 37, an Army Reserve engineer officer, hugs fellow West Point graduates and Active Duty officers Capt. Kristen Griest, 26, and 1st Lt. Shaye Haver, 25. the three women are the first female Soldiers to earn the distinctive black-and-gold Ranger tab from the combat leadership course. US Army photo by Capt. Olivia Cobiskey-Haftmann.

COD: You used to sign your work emails with a quote that often gets attributed to Albert Einstein: “A ship is always safe at shore, but that is not what it’s built for.” What is it about that quote that resonates with you?

LJ: My husband and I have a made-up term: ambient fitness. It’s the idea that I can wake up any day, and if he says, “Hey, let’s go play a game of basketball” or “Let’s go surfing,” I can say, “Yeah, let’s do it.” I don’t want to have pretty muscles if they’re not practical, just like I don’t want to be that type of smart, where I can quote a bunch of random stuff, yet I can’t have a good debate at a bar. So for me, that Einstein quote means I don’t want to look pretty on the shoreline, I want to be able to go test all these skills. It’s not about looking prepared or being there on the sidelines — it’s about going out and being tested. It’s about finding out if your training was actually quality preparation.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2022 print edition of Coffee or Die Magazine as "Delete the Adjective."

Mac Caltrider is a senior staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. He served in the US Marine Corps and is a former police officer. Caltrider earned his bachelor’s degree in history and now reads anything he can get his hands on. He is also the creator of Pipes & Pages, a site intended to increase readership among enlisted troops. Caltrider spends most of his time reading, writing, and waging a one-man war against premature hair loss.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.