How a Virginia Law Enforcement Officer Earned the Nickname ‘Deputy Hulk’

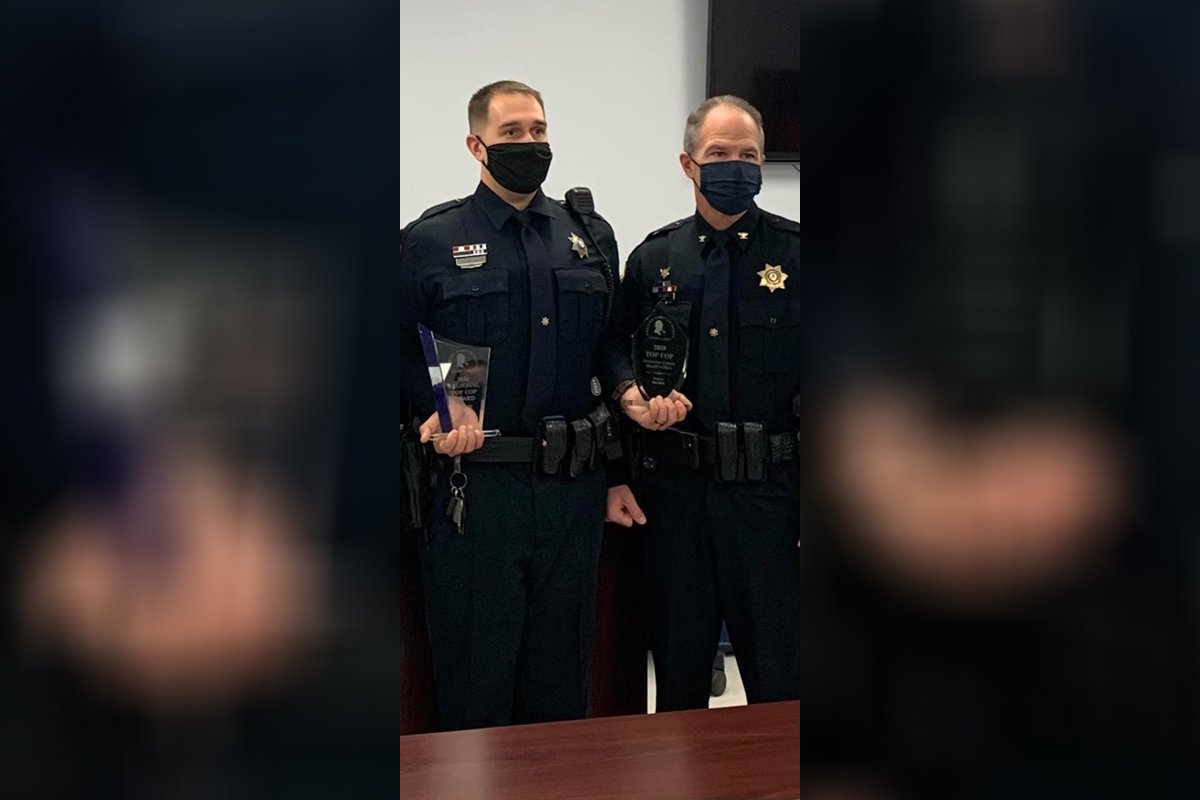

Jonathan Holt has worked as a sheriff’s deputy for seven years so far, but the stories he has, you’d think he’s had a full career already. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Holt. Composite image by Kenna Milaski/Coffee or Die Magazine.

It was Mother’s Day, and Jon Holt was on a late-night patrol down a rural Virginia highway when he saw a white SUV lose control.

“I’m thinking headlights aren’t supposed to be facing me right now,” the Gloucester County, Virginia, sheriff’s deputy recalled. “I watch it go over into the ditch. So I didn’t know how bad it was, but I believe they had struck a tree, or they were heading in that direction. This is gonna be bad.”

Holt reversed direction and pulled up to the crash site, where the white Kia was upside down, and he immediately heard a teenage girl screaming.

“She’s stuck under the car!” the girl yelled. “She can’t breathe!”

Inside the car, Holt found a 12-year-old boy crying hysterically, repeating “Mommy!” Beneath the boy, lodged halfway out of the car’s sunroof, was the children’s mother, who had been driving. Holt immediately saw that the woman had been partially ejected through the sunroof during the crash, and she was pinned under the vehicle. Holt pulled the boy from the cabin and radioed a dispatcher, “She’s trapped under the vehicle, I can’t get it off.”

But Holt also knew he had to try, a mindset ingrained in him from six years in the military.

“The first thing they say is ‘never say you can’t do anything because you just haven’t tried yet,’” Holt said.

Holt put his right shoulder — the side of his body that had taken the worst of a roadside bomb in a Baghdad, Iraq, ambush years earlier — into the SUV’s door frame and lifted with everything he had. The footage from his body camera blacks out at this point, but the audio captures Holt groaning under the weight of the vehicle as he lifts it a few precious inches. The woman lets out a loud gasp of air as the weight comes off her.

“Can you slide any, ma’am?” Holt yells on the video, still holding the vehicle up.

Miraculously, the woman quickly crawled out of the vehicle on her own.

As he waited for backup, the two teenagers had one more request: Their dog had been in the car — had he seen it? Holt told them he’d check around. But within minutes, Holt’s supervisor, Sgt. Joella Hughes, arrived and took in the scene.

Holt remembers Hughes looking right at him and saying, “Are you okay? Because you just lifted a car off somebody.”

Holt’s feat of strength surprised few in the Gloucester County Sheriff’s Office. It was not the first time Holt saved another life — or exhibited superhuman powers to do so.

According to Sheriff Darrell Warren, Holt has a reputation for action in the sheriff’s office.

“Deputy Holt never ceases to amaze us and has the unique ability of being in the right place at the right time,” Warren told Coffee or Die Magazine in a statement.

“Right place at the right time” is one way to put it. Holt said his co-workers at the sheriff’s office have chosen a different phrase: “A lot of my partners call me a ‘shit magnet.’ They are like, ‘Man, you’re a shit magnet. Doesn’t matter what’s going on, you can turn a completely peaceful day into pandemonium in under three seconds.’”

But after the Mother’s Day rescue, Holt has a new nickname around the sheriff’s office: Deputy Hulk.

An IED in Baghdad

But before earning that superhero reputation in Virginia, Jon Holt was tracking down IEDs in Iraq. He joined the Army Reserve in 2003, enlisting at 17 as a combat engineer. He deployed in 2007 as part of Task Force Iron Claw in Baghdad. His job was to find and disable improvised explosive devices.

On Oct. 25, 2007, one found him. And not just any IED but an explosively formed projectile (EFP), designed to punch through armor while setting everything on fire. Just prior to the EFP hitting his team’s armored vehicle, Holt had poured water on himself to cool off in the Baghdad heat. When the vehicle was set on fire by the explosive, the water flashed into steam, burning him severely. He was hit in both legs by shrapnel, but he escaped through the gunner’s hatch in the vehicle.

As he slid down the hood, enemy insurgents opened fire in what he realized was a complex ambush. Holt was shot in his left leg and thought, Man, they can’t just let a guy die. Luckily, a pair of Apache attack helicopters were overhead and quickly shut down the ambush as Holt and his fellow soldiers were evacuated.

Holt survived the attack that left two of his fellow soldiers dead and two others injured. He underwent two months of inpatient rehabilitation at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, where he learned to walk again. He then was transferred to Naval Medical Center Portsmouth in Virginia, where he underwent two years of outpatient rehabilitation. When Holt got word that he would be medically retired, he was happy to move on to the next chapter of his life, but he held on to some bitterness.

“At the time, I was getting a little bitter. I felt good and bad all at the same time, I guess is the best way to put it,” Holt said. “I was ready to start another chapter in my life, but I missed the military. [But I thought] I’ll give the civilian world a try, see how it goes.”

He was medically retired on Nov. 27, 2009. As he met with his doctors for final paperwork, he sat down with the respiratory doctor. She looked over his notes and then saw the file from the field hospital that treated him the day of the IED incident. She stopped on the name of one doctor.

“Hey, I know that doc,” she said — a revelation that immediately made Holt wonder if he might reconnect with one of the doctors who had saved his life. “That was me,” she said, with tears in her eyes. The doctor had intubated Holt when he was unconscious in Iraq. The chance reunion felt like a sign.

“That doc brought closure to that chapter of my life,” Holt said. “It was time to move on to the next chapter.”

Out of the military, Holt took a sales job, but he didn’t click in the position.

“As time progressed, it was like something was missing,” Holt recalled. “No bash on corporate America, but it wasn’t for me.”

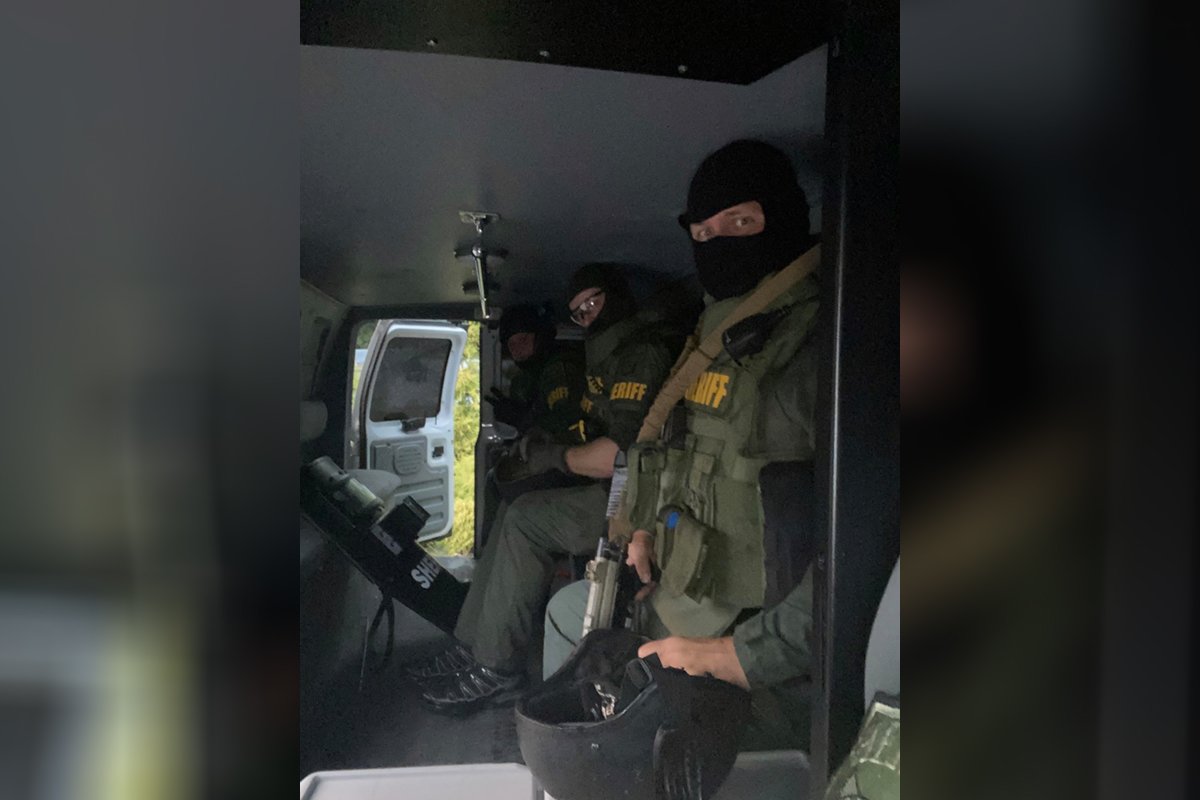

He applied for a sheriff’s office job and started out as a correctional deputy, working in the jail and courtroom system for two years before moving up to patrol. He applied to the SWAT team but had to convince a skeptical SWAT commander that his injuries would be no liability. The IED blast had torn muscle and tendon in his right leg, preventing him from being able to lift his foot upward. His answer to that was tall boots, laced extra tight, enabling him to run, jump, and everything else he needed to do to work patrol.

The SWAT commander interviewed Holt as a part of the selection process and, being former military himself, asked bluntly if his injuries in Iraq would hamper his ability to perform his duties in the faster-paced SWAT world.

“Well, you tell me,” Holt replied. “I placed third on your PT test, and I’m sitting before you right now.”

He got the spot.

Deputy Hulk Smash Fire

In March 2020, Holt was on patrol when a house-fire call came across the radio. The volunteer fire department that served his rural area would take a while to get organized, and Holt realized he was close. Rushing to the scene, he found a group of people yelling that an infant was inside the house.

Holt charged into the burning home, crawling on his hands and feet to stay under the thick smoke. He located a woman who was severely burned. Remembering the horrible sight of his fellow soldiers who were severely burned by the IED, he knew he had to be careful moving her. Holding her by the arms might tear away her burned skin. Instead, he grabbed underneath her armpits and carried her out of the house.

On the way out, he spotted a teenager stuck in the home who was not moving. He would later learn from her parents that she was autistic and had been too terrified to flee. After dropping off the woman, he ran back to retrieve the girl.

He introduced himself calmly, got the teenager moving, and escorted her to safety.

But what about the baby?

Twice more Holt went back in to find the child until a neighbor appeared: The child was already safe. She’d been lost in the chaos around the house.

Flash forward about a year, and Holt was leaving the hospital after getting checked out following the Mother’s Day rescue. He had a pulled muscle in his back, but doctors gave him the all-clear. He was sleeping not long after when animal control called him, saying they had his dog. He realized they were calling about the missing dog from the accident. He gave them the appropriate information, and the dog was reunited with its family.

“It’s just another day at the office,” Holt humbly said. “I mean, I’m just your average cop that marks on, and then just happens to be right around the areas when things go bad.”

Read Next: ‘We Have Superman With Us’ — A Family Remembers Their Hero

Joshua Skovlund is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die. He covered the 75th anniversary of D-Day in France, multinational military exercises in Germany, and civil unrest during the 2020 riots in Minneapolis. Born and raised in small-town South Dakota, he grew up playing football and soccer before serving as a forward observer in the US Army. After leaving the service, he worked as a personal trainer while earning his paramedic license. After five years as in paramedicine, he transitioned to a career in multimedia journalism. Joshua is married with two children.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.