The experimental Republic XF-84H in flight circa 1955-56. Two F-84Fs were converted into experimental aircraft, each fitted with an Allison XT40-A-1 turboprop engine of 5,850 shaft horsepower driving a supersonic propeller. Ground crews dubbed the XF-84H the “Thunderscreech” due to its extreme noise level. US Air Force photo courtesy of the US Air Force museum website.

The great thing about America is that it dreams big. The terrible thing about America is that it dreams big. Sometimes large budgets and grand ideas merge to create aircraft that seem like great ideas at a late-night brainstorming session. Occasionally those efforts lead to breakthroughs.

Other times, though, after the empty coffee cups and full ashtrays were cleaned out, someone should have also tossed the blueprints in the trash. There’s no such thing as a stupid question, but there is often such a thing as a stupid idea.

It takes more than just being too slow or not being maneuverable enough to make the pantheon of suckitude. It takes a fundamental misreading of the requirements and threats combined with enough determination to actually build such a ridiculous thing.

These aircraft made it to the actual demonstration or prototype phase, costing many man-years and many dollars before anyone had the gumption to say, “Uh, hold on a second …”

XF-85 Goblin

Until fighters like the P-51 Mustang were able to escort them into Germany, enemy interceptors were the bane of American bombers. Before ICBMs, America’s nuclear deterrent depended on strategic bombers being able to fly deep into the Soviet Union.

There aren’t any fighters able to fly from the US to Russia in 2021, much less in the late 1940s. Someone had the ingenious idea of having some of the bombers carry three tiny and incredibly crappy fighters inside their bomb bays, and thus the XF-85 Goblin was born.

The first thing one might ask upon seeing the Goblin might be “What the hell is that?” followed shortly thereafter with “Doesn’t it need bigger wings and more space for an engine, fuel, and weapons?”

Yes, it did need those things. It would have been annihilated by even the worst Soviet aircraft, at least any it encountered in the space of 30 minutes, because that’s the extent of time it could fly on the fuel it had. As it turned out though, the Goblin was so difficult to re-dock with its mother ship that facing enemy fighters might have been the least of the pilot’s worries.

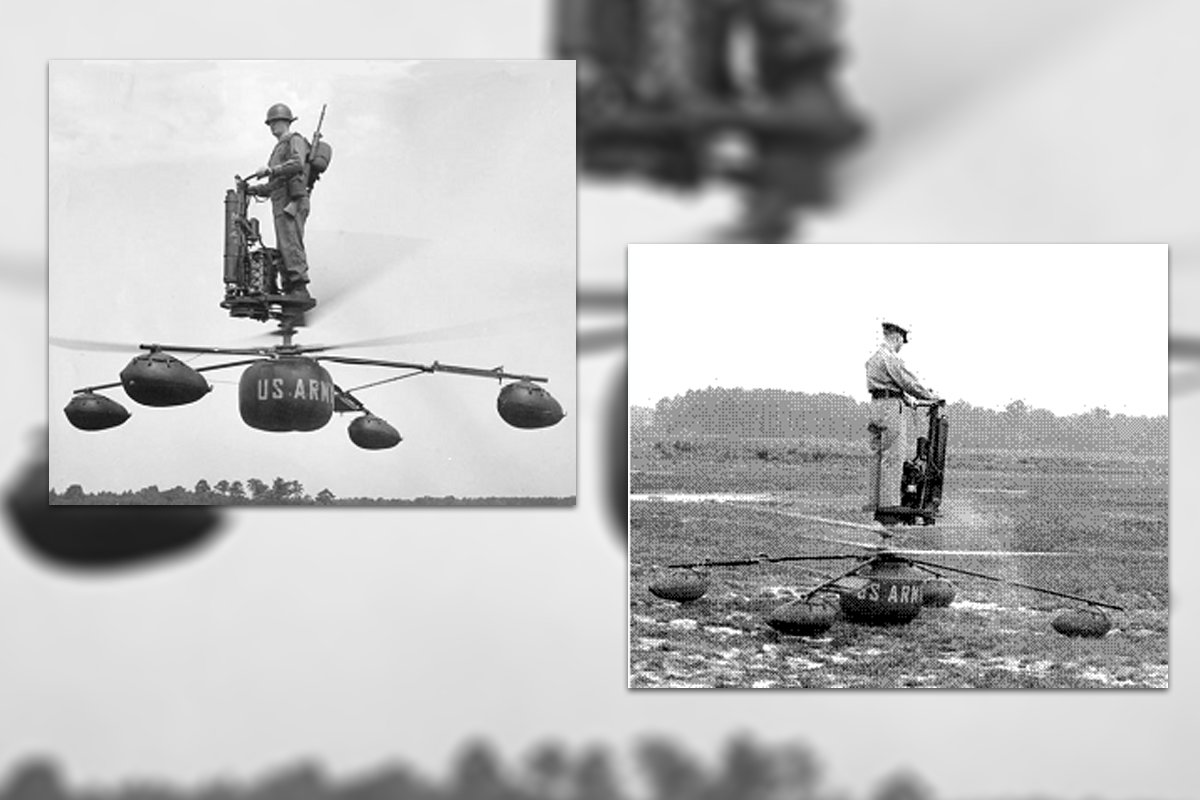

HZ-1 Aerocycle

In the 1950s, there were several experimental one-man scouting aircraft proposed and prototyped. The idea makes a little bit of sense. It’d be great if an Army unit could put a man on a flying platform to get a look at things a few terrain features away.

All these concepts were dubious within the technology of the day. The Army envisioned a flying Segway 50 years before actual Segways, flying after a couple of hours of training just by leaning in the desired direction.

There’s a reason aircraft are, well, aircraft, and need pilots. It’s a little harder than that, and if you look at pictures of the Aerocycle, there’s a particular incentive to not screw up — two sets of counter-rotating blades underneath the operator, ready to turn him into meat pudding.

XF-84H Thunderscreech

In the early 1950s, jets were still in their infancy. Perhaps there was a way to get the best of both worlds. Turboprop aircraft used jet turbines to achieve greater power than reciprocating engines and more immediate power response than turbojets of the day.

The F-84 was a reasonably successful jet fighter in the Korean War, but what if you used that jet engine to drive a propeller? There are reasons propeller aircraft have top speeds, and one of them is that supersonic airflow behaves much differently than subsonic. To get jet speed out of a turboprop, the XF-84H used special props built to work at supersonic speed.

It wasn’t the airplane itself that was going supersonic, though. That would have been too much to ask. It was the tips of the propellers that were going supersonic — and making sonic booms with every rotation, incapacitating ground personnel, as well as making the aircraft vibrate with such intensity it made pilots physically ill.

The aircraft were retired after not even 10 hours of total flight time, and hitting only 450 mph, far short of the 670 promised by Republic.

Goodyear Inflatoplane

Goodyear is a company famous for making rubber products. As aircraft go, it is most famous for its ubiquitous Goodyear Blimp, often seen over major sporting events.

It once had an airplane program befitting its inflatable heritage, though. Normal airplanes take weeks or months to build, but if you could inflate one, you could drop one down to a downed pilot, and given several hours and a long, flat area, he could fly himself to safety at a blistering 50 mph. Thus the Goodyear Inflatoplane program was born.

Even at the program’s beginning in 1956, it was a questionable premise. Helicopters had already proven themselves in Korea. If you have enough runway and are unconcerned enough about the enemy to launch your enormous rubber airplane to freedom, perhaps there are other ways for friendly forces to come get you.

Nevertheless, even after the Navy dropped out for these self-evident reasons, the Army and Marines stuck with the idea for reconnaissance and even cargo transport. The Inflatoplane was under development until 1973. That’s right. Freaks and Geeks lasted one season, but the United States worked on an inflatable airplane for nearly 20 years.

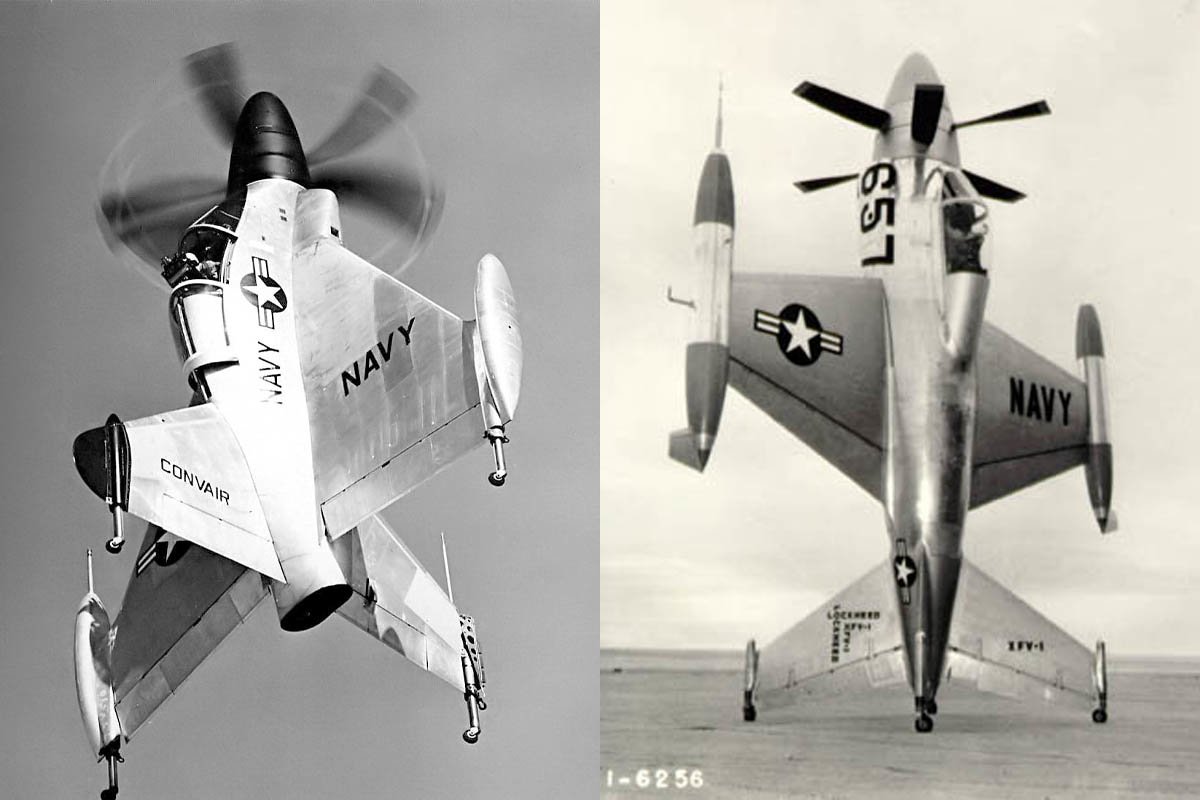

Convair XFY Pogo and Lockheed XFV Salmon

These two aircraft were born out of a requirement to put interceptor aircraft aboard ships that weren’t aircraft carriers. Convoys of ships saved Great Britain during World War II, and they were seen as essential in the looming World War III.

Years later, technology had advanced to the point where vectored thrust could make a somewhat adequate V/STOL — vertical and/or short takeoff and landing — fighter. In 1951, the best idea both Lockheed and Convair could come up with was to put the landing gear on the back of the plane and point it straight up at the sky.

That wasn’t a bad idea for takeoff. Landing was another matter altogether. Helicopters are known to be difficult to control in a hover, and in those, the pilot isn’t looking straight up at the sky. Pilots had an extraordinarily difficult time judging the rate of descent in both the Pogo and the Salmon. The first pilot to successfully land the Pogo on its tail got an award for it.

Its dream of a fighter on every boat dashed on the rocks of ridiculousness, the Navy scuttled the program in 1955.

Albert Einstein said, “The true sign of intelligence is not knowledge but imagination.” Innovation is born by thinking outside the box. What is often neglected is Ice Cube’s corollary, “Check yourself before you wreck yourself.” Common sense is often an uncommon virtue. Engineers need to balance both in order to make the aircraft needed for America’s defense.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that “the United States worked on an inflatable airplane for over a quarter of a century.” The text has been corrected to reflect the accurate timeframe of nearly 20 years. We regret the error.

Read Next:

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.