Ernest Hemingway: The Highly Decorated Soldier Who Never Served

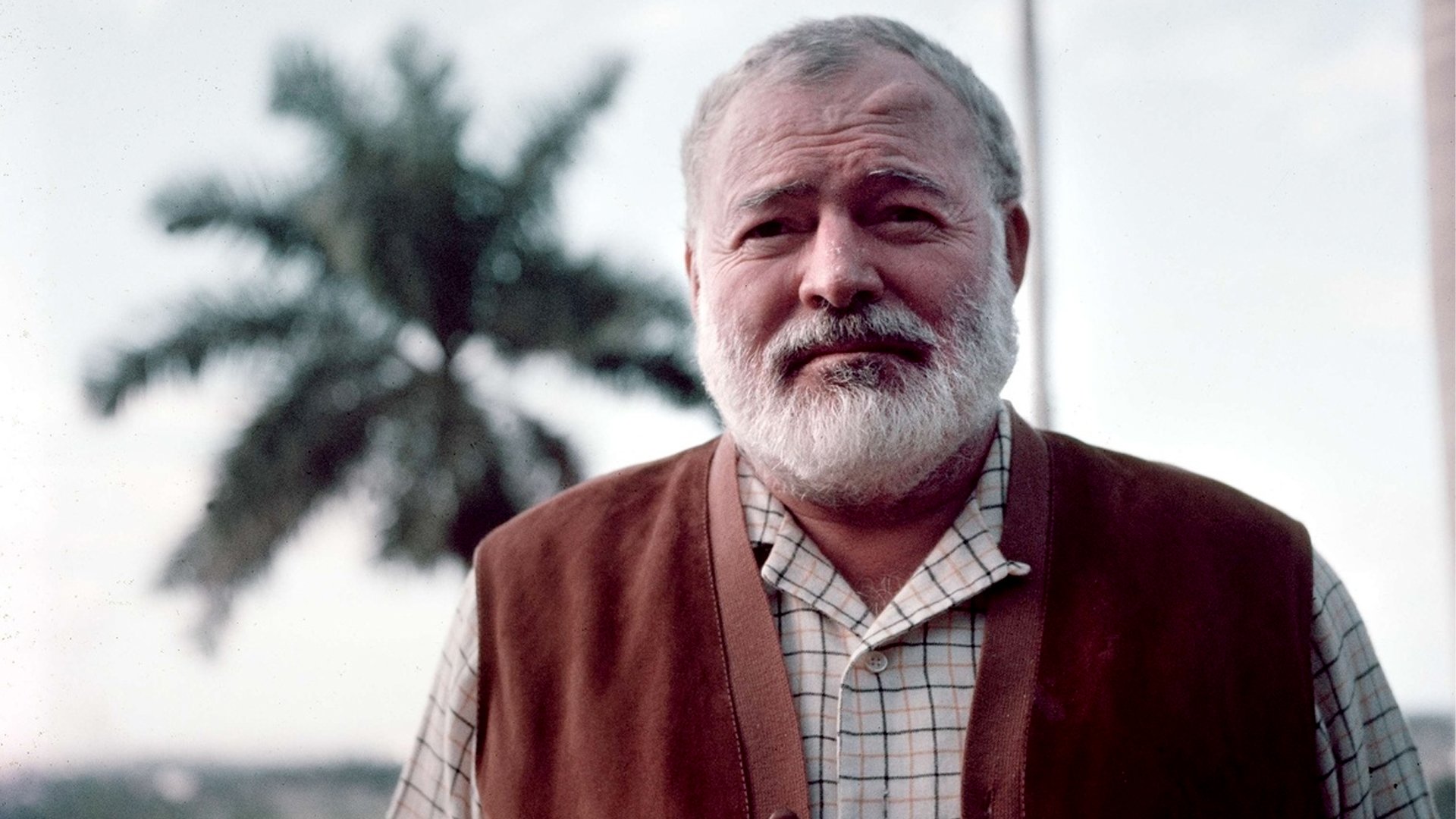

Ernest Hemingway at his home in Finca Vigía, San Francisco de Paula, Cuba. 1954. Photo by Hans Malmberg, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Ernest Hemingway is considered one of the greatest American writers. Known for his minimalist writing style, he pioneered the use of omission to accentuate thematic undercurrents in his work. His reputation was also defined by his experiences at war and his voracious appetite for adventure.

Hemingway spent a great deal of time in conflict zones and wrote many stories about people he encountered on the front lines. Interestingly, the big-game hunter and bullfighting aficionado, who penned such classic war novels as A Farewell to Arms and For Whom the Bell Tolls, never actually served in the military. But that didn’t stop Papa from participating in both world wars and accruing multiple decorations for valor.

Related: ‘Soldier’s Home’ Is the Hemingway Short Story Every Veteran Should Read

Ernest Goes to War

Born in 1899, Hemingway grew up in the suburbs of Chicago. He loved competition and the outdoors. His father taught him to hunt and fish during family excursions in Northern Michigan, and as a teenager he excelled at boxing and football.

In 1917 — the year the United States entered World War I — Hemingway tried to enlist in the Army but was turned away because of his bad eyesight. So the young adventurer took a different path to the war in Europe: He volunteered to serve with the Red Cross.

In the spring of 1918, Hemingway was sent to Europe to work as an ambulance driver. After a brief stint in France, he was transferred to the Italian front, where he immediately came face-to-face with the gruesome reality of war. On his first day in Italy, he helped recover the remains of civilians killed by an explosion at an ammunition factory.

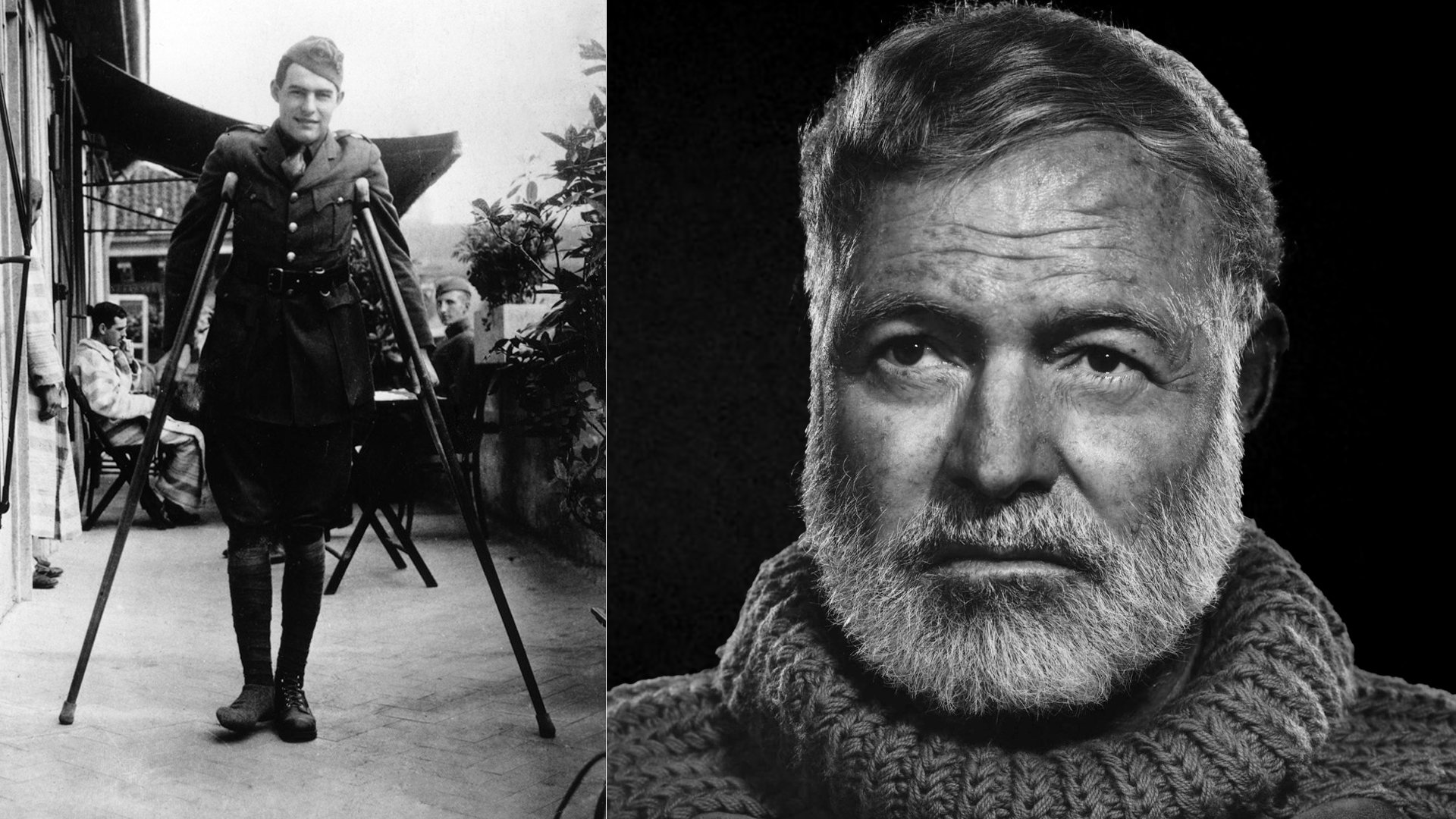

Ernest Hemingway, American Red Cross volunteer, recuperates from wounds at ARC Hospital, Milan, Italy, September 1918. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Days later, Hemingway was delivering candy and cigarettes to soldiers in the trenches when he was struck by an Austrian mortar. The blast knocked him unconscious and riddled his legs with shrapnel. After coming to, Hemingway was wounded again, by machine-gun fire, while carrying a more severely injured Italian soldier to an aid station. He was awarded the Italian War Merit Cross for his actions.

Hemingway was sent to a hospital in Milan to recover from his wounds. As the story goes, while there, he met a nurse named Agnes von Kurowsky and the two fell in love. Then Hemingway returned to Illinois and Kurowsky remained in Italy, bringing their passionate love affair to an end. Yet the memory of their fleeting romance would forever endure as the basis for Hemingway’s most famous novel, A Farewell to Arms.

Related: Ernest Hemingway and the KGB: A Secret Life of Espionage and Covert Ops

Papa Returns to the Front

His first professional writing gig was as a freelance journalist for the Toronto Star. The publication eventually promoted him to the job of foreign correspondent, which allowed him to move to Paris. Once he was settled in Europe, Hemingway wasted no time returning to conflict for material.

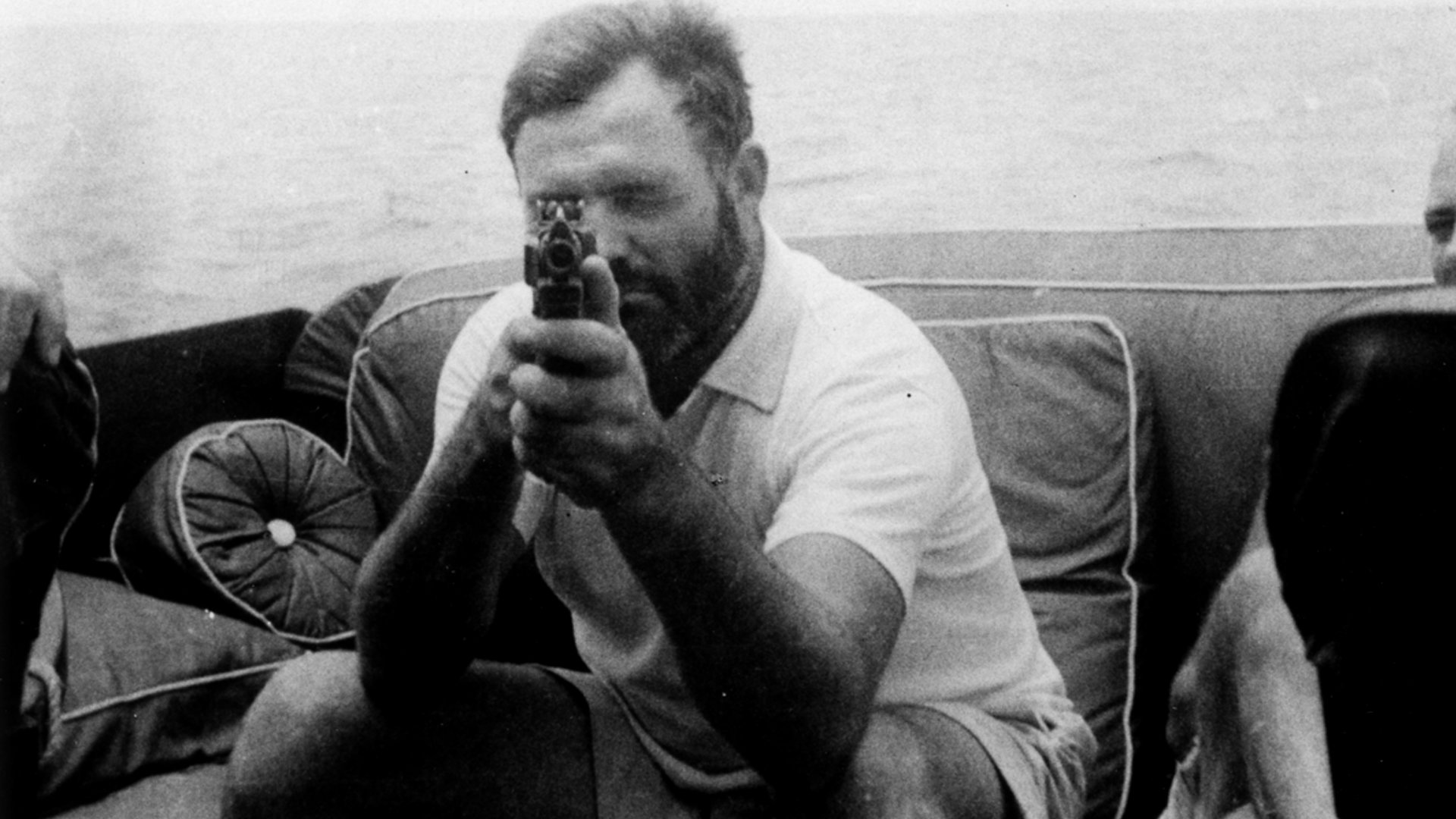

Ernest Hemingway, holding a Tommy gun, aboard his yacht, the Pilar. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In September 1922, Hemingway traveled to Turkey to cover the Greco-Turkish War. While there, he witnessed the Great Fire of Smyrna, a catastrophe that claimed the lives of an estimated 10,000 to 125,000 Greek and Armenian civilians.

The following year, Hemingway published his first book, Three Stories and Ten Poems. Over the next decade, he produced some of his most famous works, including The Sun Also Rises, a semi-autobiographical novel about a disillusioned American war veteran living in Paris in the wake of World War I.

Related: The Legend of Jack Hemingway: OSS Commando, Fly Fisherman, POW, Writer

A Front Seat to the Spanish Civil War

Hemingway returned once again to Europe in 1937, this time to cover the civil war in Spain. During his trip, he wrote a series of dispatches for the North American Newspaper Alliance, as well as Old Man at the Bridge, a short story about a Spanish civilian caught between the war’s opposing factions.

Hemingway was in Madrid during a prolonged aerial bombardment of the city by Nationalist forces. During the bombardment, Hemingway penned his one and only play, The Fifth Column, about an American secret agent working undercover in Spain during the war.

Hemingway traveled back to Spain two more times in 1938. He was there to witness the largest battle ever fought in the country — the Battle of the Erbo. The fighting raged for four months and inflicted devastating losses on both sides. Casualty estimates range from 60,000 to 100,000 combatants. The Nationalists won the battle and then the war the following spring.

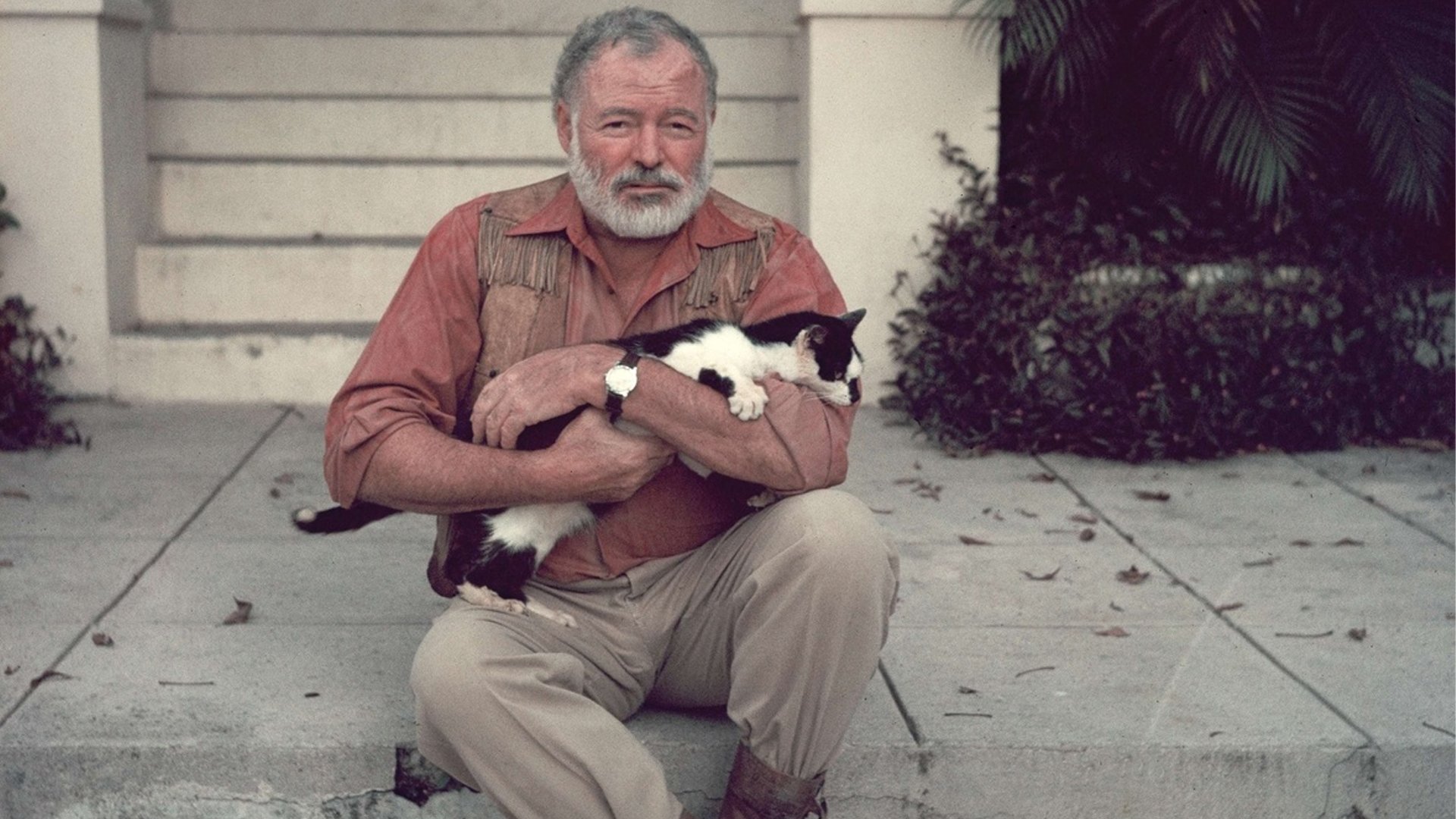

Hemingway at his home in Finca Vigía, San Francisco de Paula, Cuba, with a cat, 1954. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Hemingway drew on his experiences in Spain to write several short stories, as well as the novel For Whom the Bell Tolls, which he completed in 1940.

Related: How Hemingway’s ‘For Whom The Bell Tolls’ Provides Insight Into Modern Special Forces

D-Day, a Private Militia, and a Bronze Star

Less than four years after publishing For Whom the Bell Tolls, Hemingway found himself bound for the battlefields of another world war. This time, his journey to the front lines began as a journalist on an Allied armada floating toward the fortified coast of Normandy for the largest amphibious invasion in human history.

The invasion commenced on June 6, 1944. Hemingway waited on board a landing craft in the English Channel as 160,000 troops waded ashore amid a maelstrom of machine-gun and mortar fire. Though he was still nursing a severe head wound from a car accident weeks earlier, the 45-year-old writer intended to join the grunts on the beach and chronicle the battle. However, like many other war correspondents who were there that day, he was denied permission to leave the boat.

The following month, Hemingway attached himself to the US Army’s 22nd Infantry Regiment during their march to Paris. Near the village of Rambouillet, he came upon the bodies of American soldiers scattered in the road. Seeing the carnage compelled Papa to put down his pen and pick up a gun. Then he rallied a group of French resistance fighters and led the guerrilla outfit into Rambouillet. They found the village abandoned and loaded with booby traps left by the Germans. Hemingway relayed this information to a group from the 22nd Infantry, and a team of sappers was called in to clear the path of explosives.

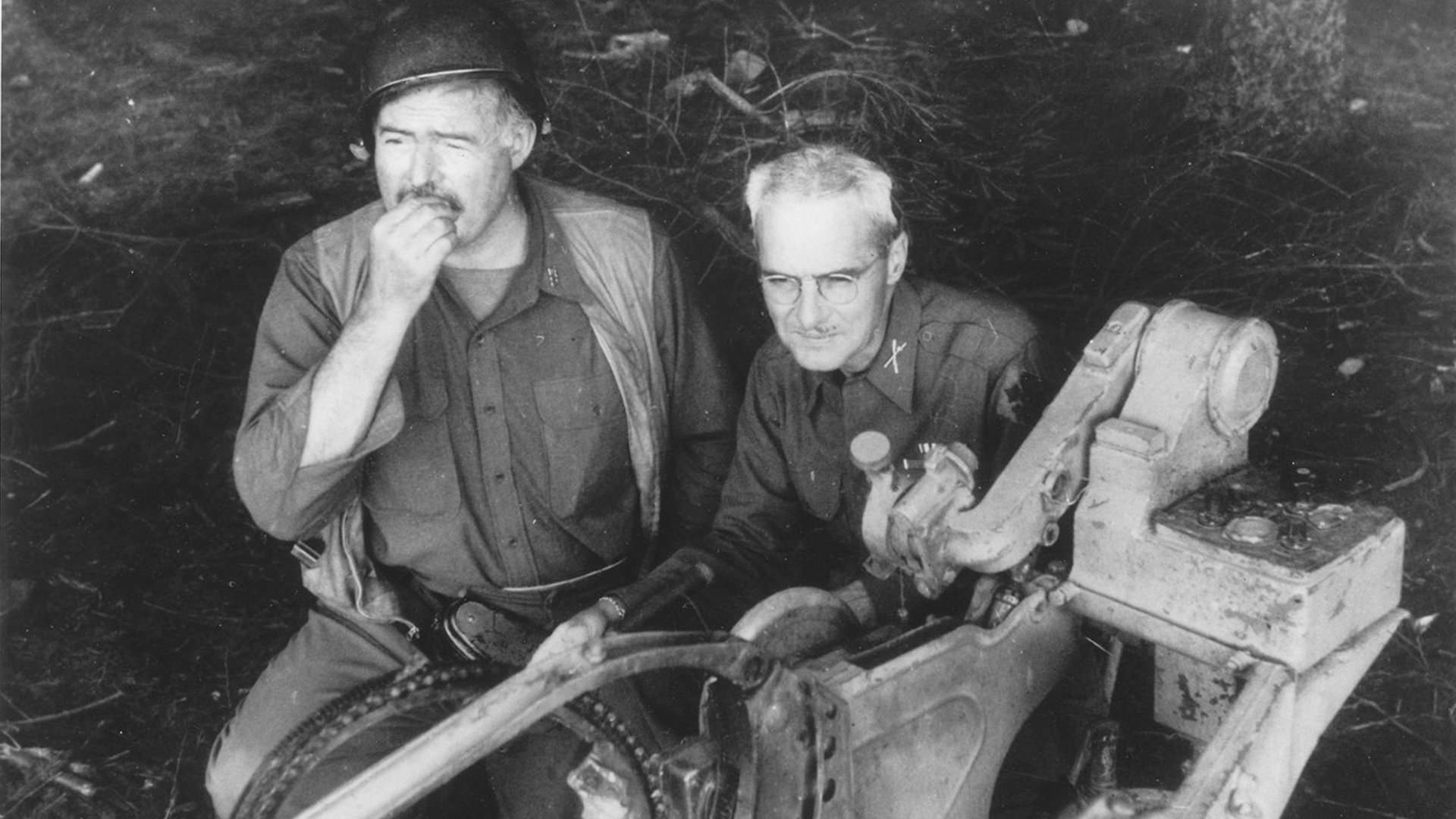

Hemingway with Col. Charles T. (Buck) Lanham in Germany, Sept. 18, 1944. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Hemingway was later criticized for his conduct in Rambouillet. His critics accused him of ignoring the Geneva Convention, which forbids journalists from taking up arms in the conflicts on which they are reporting. The Third Army’s inspector general even launched an official investigation into the matter. But not only was Hemingway cleared of any wrongdoing, he was also awarded a Bronze Star for his service as a war correspondent.

In a letter published in the New York Times in 1951, Hemingway defended his decision to become a guerrilla commander for a day. Citing the fact that he was only responsible for completing one article per month during the war, he argued that he was only a part-time journalist and therefore not bound by Article 13 of the Geneva Convention in the periods when he wasn’t working in that capacity. He also noted his credentials as a soldier.

“I had a certain amount of knowledge about guerilla warfare and irregular tactics,” he wrote. “As well as a grounding in more formal war and I was willing and happy to work for or be of use to anybody who would give me anything to do within my capabilities.”

Related: Calls for Afghan War Accountability Echo Hemingway’s ‘Who Murdered the Vets?’

Surviving Mortars, Two Plane Crashes, and a Brushfire

The Second World War closed the chapter on Hemingway’s career as a conflict reporter. He would never step foot in an active war zone again. Yet many perilous adventures still lay ahead.

In 1954, while traveling in Africa with his fourth wife, Mary Welsh Hemingway, Papa chartered a small plane for a sightseeing excursion over Uganda’s Murchison Falls. The pilot was forced to make an emergency landing to avoid a flock of birds and crashed into the ground along an elephant path. Everyone on board survived the accident without any major injuries. They also managed to make it through the night despite the wild elephants roaming nearby. According to the New York Times, Hemingway emerged from the jungle the next morning carrying a bushel of bananas and a bottle of gin. Smiling, he quipped, “My luck, she is running very good.”

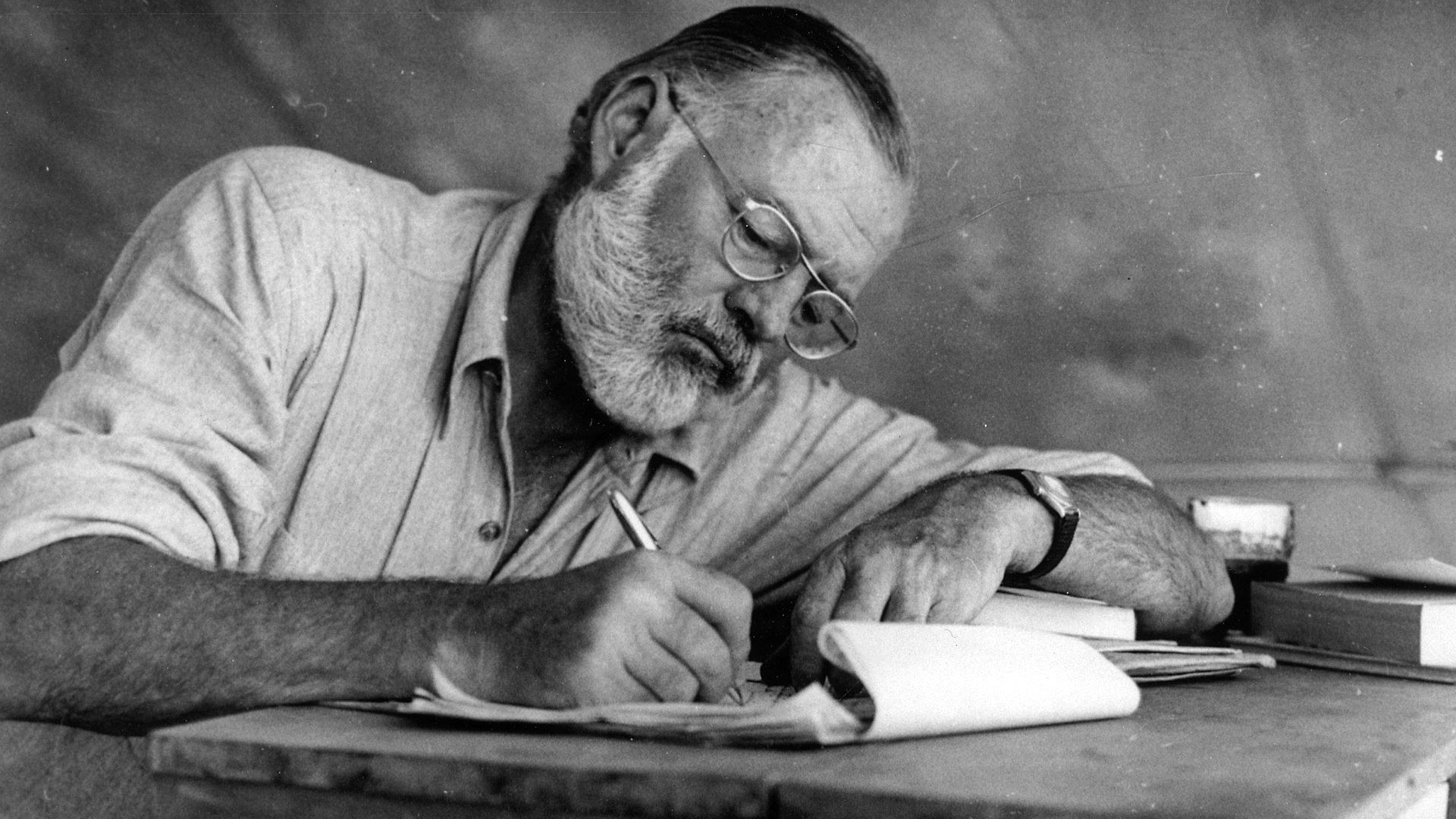

Hemingway sitting at a table writing while at his campsite in Kenya, 1953. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The following day, Hemingway boarded another plane, this one bound for a hospital. Shortly after takeoff, the single-engine Cessna caught fire and had to make an emergency landing. Once again, everyone on board survived — however, Hemingway suffered a cracked skull, a ruptured kidney, a ruptured liver, a dislocated shoulder, and two damaged lumbar discs. Then, several days later, Hemingway got caught in the middle of a brush fire and suffered second-degree burns over much of his body.

Throughout his life, Hemingway survived a seemingly endless stream of potentially life-threatening injuries. He survived mortar shrapnel in World War I, several more blasts in World War II, two serious car accidents, two plane crashes, a fall from the bridge of a fishing boat, a fire, and a number of serious head wounds. Hemingway said it was luck that kept him alive, but there are some who would argue that all of his close brushes with death are what ultimately killed him. In his book, Hemingway’s Brain, Dr. Andrew Farah claims Hemingway’s repeated concussions resulted in chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) — a brain injury often associated with professional football players that is known to be a contributing factor in suicides.

On July 2, 1961, Hemingway killed himself at his home in Ketchum, Idaho.

Read Next: 5 Hemingway Quotes on Life and How to Live and How to Die

Mac Caltrider is a senior staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. He served in the US Marine Corps and is a former police officer. Caltrider earned his bachelor’s degree in history and now reads anything he can get his hands on. He is also the creator of Pipes & Pages, a site intended to increase readership among enlisted troops. Caltrider spends most of his time reading, writing, and waging a one-man war against premature hair loss.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.