This Mexican American POW Survived 8.5 Years Inside the ‘Hanoi Hilton’

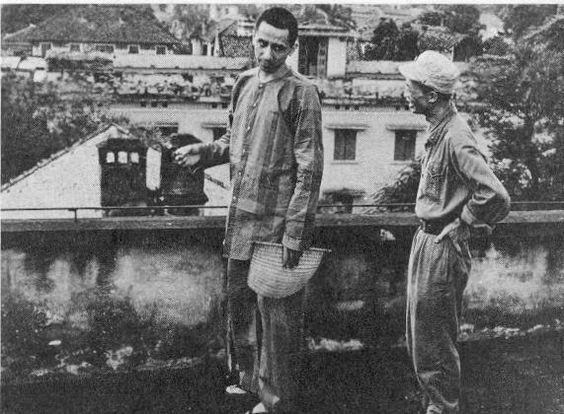

Everett Alvarez Jr. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

US Navy Lt. j.g. Everett Alvarez Jr. survived more than eight years as a prisoner of war inside North Vietnam’s notorious Hoa Lo prison in Hanoi. The North Vietnamese called the prison the “fiery furnace,” while Americans sarcastically nicknamed it the Hanoi Hilton in a reference to the international hotel chain.

The first aviator taken captive after being shot down over North Vietnam, Alvarez spent the second-longest tenure in a North Vietnamese POW camp, behind Army Special Forces soldier Maj. Floyd Thompson’s nine years.

Alvarez’s ordeal began in early August 1964, when North Vietnamese torpedo boats confronted and allegedly fired upon US Navy warships stationed in the Gulf of Tonkin in Vietnam. This disputed naval encounter spurred the US military to escalate its involvement in the Vietnam War. In response to the so-called “Gulf of Tonkin Incident,” the US military launched Operation Pierce Arrow, a retaliatory strike against bases situated along the coast of North Vietnam.

At the time, Alvarez was an A-4 Skyhawk pilot aboard the USS Constellation. The 32-year-old Mexican American was briefed on his mission: The target was a torpedo boat base near the Vietnam-China border at Hon Gai.

On Aug. 5, 1964, Alvarez and his squadron of about 10 planes took off. It took them about two and a half hours to fly some 400 miles to the target strike zone.

“On my first pass, I fired all my rockets,” Alvarez told HistoryNet. “Coming on my second pass, I flipped on my 20mm guns and made a strafing pass, blasting the torpedo boats.”

Following his executive officer over Hon Gai Bay, Alvarez leveled out just over the treetops. He was headed out to sea and going around 500 mph when disaster struck.

“Then I hear this big ‘poof’ — I’m hit,” Alvarez said in the interview. “I immediately lost control of the plane, lost lift, rolled inverted and just clung there vertically about 60 degrees from the upright. I knew if I waited, I definitely wouldn’t survive.”

Alvarez ejected and descended to the water under his parachute. Once down, he immediately pulled off his face mask, ripped off his helmet, and was splashed with black-dyed shark repellent once the container broke loose in his survival vest. A pair of sampan boats approached. Soon thereafter, Alvarez was captured by North Vietnamese fishermen who brought him to a local jail. The American prisoner stayed there one night before he was moved to a farmhouse. The North Vietnamese had feared a rescue attempt was imminent. After a week at the farmhouse, Alvarez’s captors moved him to the Hoa Lo prison in Hanoi — a facility notorious for its harsh and inhumane conditions.

Alvarez survived on a starvation diet. His rations included chicken heads, animal hooves covered in drain water, and even a blackbird that was served feet up on a plate with all its feathers still attached and its eyes wide open. A bout of vomiting normally followed such wretched fare.

To maintain his sanity, Alvarez mentally replayed old memories spanning from childhood to his time on the Gulf of Tonkin. Early on, gallows humor got him through the serious interrogations.

Alvarez learned how to talk to his captors without actually saying anything. “I explained to them, in great detail, that my primary job on the ship was running the popcorn machine,” he told HistoryNet. “It took days for me to explain that to them. They wanted to know what popcorn was. The more I talked to them about popcorn and the popcorn machine, they’d bring in others and I’d have to explain it all over again.”

As one of the first American POWs in North Vietnam, Alvarez didn’t gain a cellmate for at least a year. According to his book, Chained Eagle: The Heroic Story of the First American Shot Down Over North Vietnam, Alvarez spent 15 and a half months in solitary confinement in a cell he described as a “concrete straightjacket.”

Once more Americans were taken prisoner, they established covert methods of communication. One of these methods was a so-called “tap code”: POWs followed a five-by-five grid in which the number of taps correlated to letters of the alphabet. These letters were tapped out to form words.

The tap-code method improved morale and kept the Americans’ communications hidden from their North Vietnamese guards.

After eight and a half years of captivity, Alvarez was one of 591 American POWs liberated during Operation Homecoming in 1973. He was awarded several medals for valor, including the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Silver Star. He retired from the US Navy in 1980 and became deputy director of the Peace Corps.

The years of torture and malnourishment took their toll on Alvarez’s body — he still suffers from nerve damage and arthritis linked to broken bones and other injuries he suffered while in confinement. Still, Alvarez didn’t allow his injuries to stop his extraordinary career as an entrepreneur.

Alvarez launched his first business in 1988 and sold it in 2003. He launched Alvarez & Associates, now Alvarez LLC, in 2004 and has managed information technology contracts for the US government. In 2013, the company recorded $180 million in revenues.

“My whole life since then has been pursuing those dreams that I thought about as I was sitting in those cells,” Alvarez told the BBC in a 2014 interview. “I’ve never looked back, always looked forward.”

Read Next: How This Three-War Double Ace Became a MiG Killer

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.