A U.S. Army Task Force Brawler CH-47F Chinook releases flares while conducting a training exercise with a Guardian Angel team assigned to the 83rd Expeditionary Rescue Squadron at Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan, March 26, 2018. U.S. Air Force Courtesy Photo Edited by Tech. Sgt. Gregory Brook.

The following passage is an excerpt from “Violence of Action: The Untold Stories of the 75th Ranger Regiment in the War on Terror.” It has been edited for clarity.

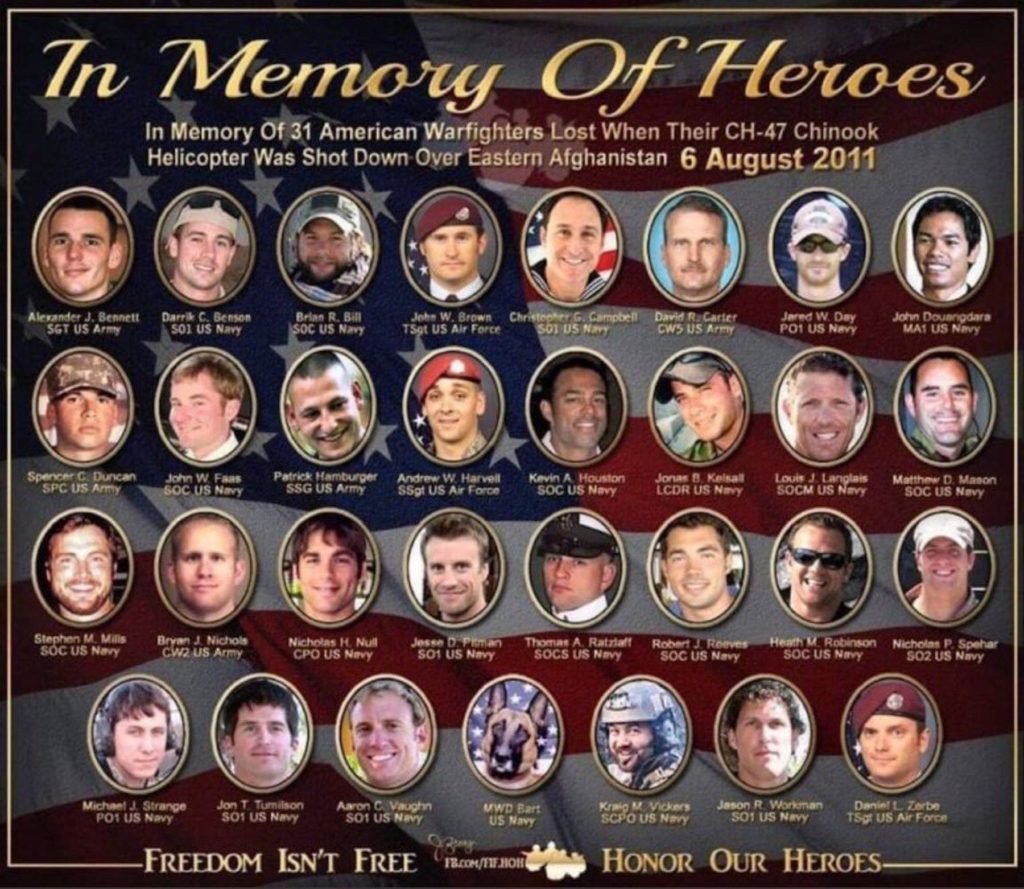

On the night of Aug. 5 through Aug. 6, 2011, one of the worst tragedies in modern special operations history occurred. By this point in the war, the men who made up the special operations community were some of the most proficient and combat-hardened warriors the world had ever seen. Even so, the enemy always has a vote.

The men of 1st Platoon, Bravo Company, 2nd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment were on a longer-than-normal deployment as the rest of their company was on Team Merrill and they surged ahead with them.

They had yet another raid mission in pursuit of a high-value target in the Tangi Valley, which was in Wardak Province, Afghanistan, on the night of August 5.

The mission was not easy. The Rangers took contact not only during their movement to the target but also on the target. Despite the tough fight that left some wounded, the enemy combatants were no match for the Ranger platoon. They secured the target and were gathering anything of value for intelligence when it was suggested by the Joint Operations Center (JOC) back at the Forward Operating Base (FOB) that a platoon of SEALs from a Naval Special Mission Unit be launched to chase down the three or four combatants that ran, or squirted, from the target.

This was a notoriously bad area, and the Ranger platoon sergeant responded that they did not want the aerial containment that was offered at that time. The decision was made to launch anyway. The platoon-sized element boarded a CH-47D Chinook, callsign Extortion 17, as no SOF air assets were available on that short of notice.

As Extortion 17 moved into final approach of the target area at 0238 local time, the Rangers on the ground watched in horror as it took a direct hit from an RPG (rocket-propelled grenade). The helicopter fell from the sky, killing all 38 on board. The call came over the radio that they had a helicopter down, and the platoon stopped what they were doing to move to the crash site immediately. Because of the urgency of the situation, they left behind the detainees they fought hard to capture.

The platoon moved as fast as possible, covering 7 kilometers of the rugged terrain at a running pace, arriving in under an hour. They risked further danger by moving on roads that were known to have IEDs (improvised explosive devices) to arrive at the crash site as fast as they could, as they were receiving real-time intelligence that the enemy was moving to the crash site to set up an ambush.

Upon their arrival, they found a crash site still on fire. Some of those on board did not have their safety lines attached and were thrown from the helicopter, which scattered them away from the crash site, so the platoon’s medical personnel went to them first to check for any signs of life. With no luck, they then began gathering the remains of the fallen and their sensitive items.

Similar to the Jessica Lynch rescue mission almost a decade prior, the Rangers on the ground decided to push as many guys as possible out on security to spare them from the gruesome task. Approximately six Rangers took on the lion’s share of the work. They attempted to bring down two of the attached cultural support team (CST) members, but had to send them back as they quickly lost their composure at the sight of it all. On top of that, the crashed aircraft experienced a secondary explosion after the Rangers arrived that sent shrapnel into two of the medics helping to gather bodies.

Despite their injuries, they kept working. Later in the day they had to deal with a flash flood from enemy fighters releasing dammed water into the irrigation canal running through the crash site in an attempt to separate the Ranger platoon, cutting them in half. Luckily, because of the sheer amount of water heading toward them, they heard it before it hit them and were moved out of the way before anyone was hurt. If that wasn’t enough, there was also an afternoon lightning storm that was so intense it left some of their equipment inoperable and their platoon without aerial fire support.

Meanwhile, 3rd Platoon, Delta Company from 1st Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment was alerted after coming off a mission of their own. They took a small break to get some sleep before they flew out to replace the other platoon, which would hold the site through the day. Once they awoke, they were told to prepare to stay out for a few days. They rode out and landed at the nearest Helicopter Landing Zone (HLZ), 7 kilometers from the crash site, and made their way in with an Air Force CSAR team in tow.

After arriving, the platoon from 2/75 had to make the 7-kilometer trek back to the HLZ, as that was the nearest place a helicopter could land in the rugged terrain. The men were exhausted, having walked to their objective the night before, fighting all night, running to the crash site, securing it through the day only to execute another long movement to exfil.

New to the scene, the platoon from 1/75 did what they could to disassemble the helicopter and prepare it to be moved. The last platoon evacuated the bodies and sensitive items on board, so now the only thing left was the large pieces of the aircraft spread out across three locations. They were out for three days straight, using demolitions as well as torches to cut the aircraft into moveable sections and then loading them onto vehicles that the conventional Army unit that owned the battlespace brought in.

Despite the gruesome and sobering task, Rangers worked until the mission was accomplished. The third stanza of the Ranger Creed states that you will never fail your comrades and that you will shoulder more than your fair share of the task, whatever it may be, 100 percent and then some. The Rangers of these two platoons more than lived the Creed in response to the Extortion 17 tragedy.

Marty Skovlund Jr. was the executive editor of Coffee or Die. As a journalist, Marty has covered the Standing Rock protest in North Dakota, embedded with American special operation forces in Afghanistan, and broken stories about the first females to make it through infantry training and Ranger selection. He has also published two books, appeared as a co-host on History Channel’s JFK Declassified, and produced multiple award-winning independent films.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.