How a Sculptor Transformed Facial Reconstruction for World War I Veterans

French “mutilé” before and after being fitted with a mask by Anna Coleman Ladd of the American Red Cross. Photos courtesy of the Library of Congress.

As the bullets and shrapnel of World War I left thousands of soldiers with horrific facial disfigurement, one American sculptor better known for her bronze works set out for Europe to leverage her talents to support wounded veterans.

World War I marked a new, deadlier era of battlefield weapons. War victims’ wounds were often the outcome of artillery bombardments and large-caliber machine guns. Medical advances struggled to keep up, and plastic surgeons, doctors, and nurses in Europe faced insurmountable challenges providing treatments to the approximately 20,000 veterans whose faces were mangled in the fighting.

When American sculptor Anna Coleman Ladd heard of Francis Derwent Wood’s groundbreaking facial reconstruction work in London, she, too, felt compelled to help the wounded of World War I.

Ladd was born in Philadelphia in 1878 and raised in Paris. As an adult, she became a coveted bronze artist in Boston, but she traveled back to France in 1917 to open the American Red Cross Studio for Portrait Masks.

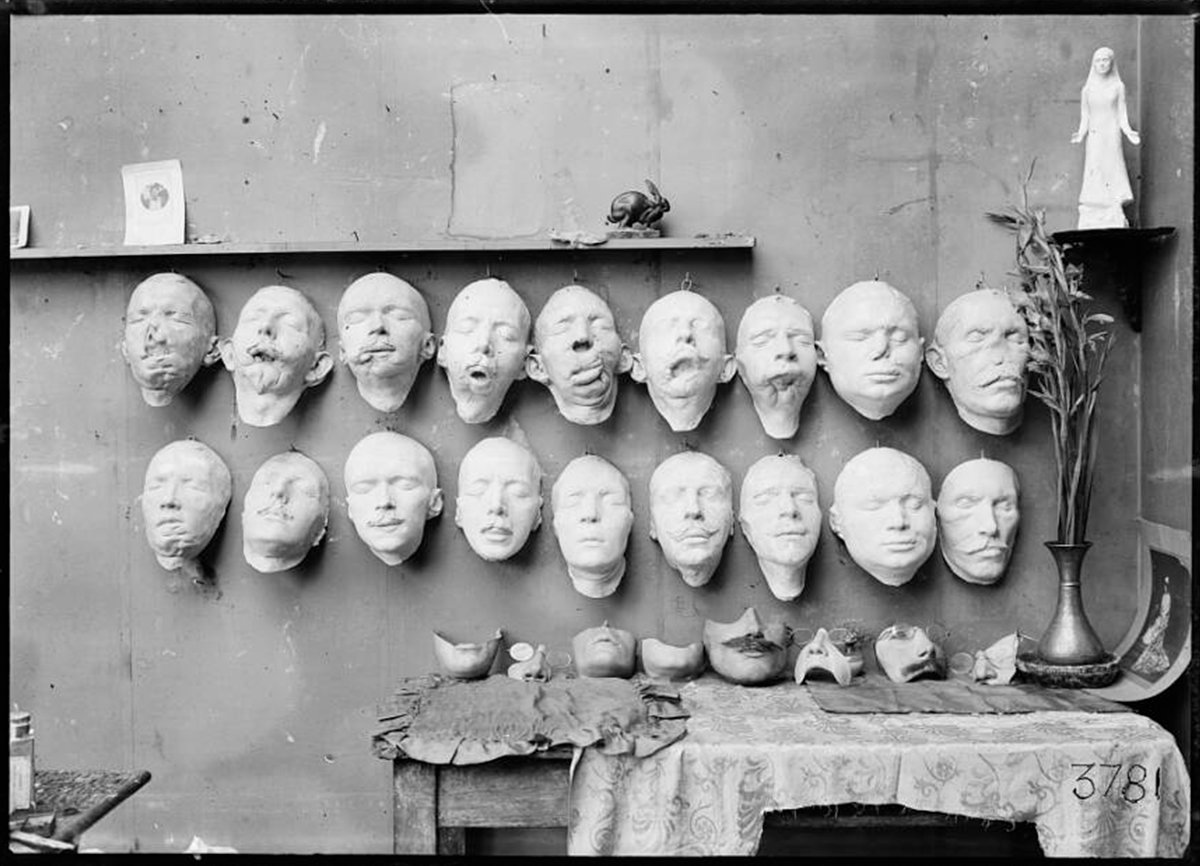

Ladd and her team of dedicated helpers ensured their Parisian studio offered a welcoming atmosphere for patients. The rooms were filled with flowers, posters of American and French flags hung from the walls, and rows of plaster casts of masks that were works in progress. It gave patients hope for their potential new appearances.

Each patient’s mask required about a month of labor from Ladd and her team.

“They made casts of injured faces, then sculpted attachments that restored the face,” Vox reported in a 2018 video. “These were then used to make paper-thin copper-plated attachments, which Ladd and others then painted.”

Ladd and her four assistants even used natural hair to create eyebrows, eyelashes, and mustaches. These mask attachments, often held together on the person’s face by a pair of glasses, aimed to diminish the physical, psychological, and social issues created from the war and allow patients to adapt to their post-war lives.

Ladd’s studio had produced 185 masks by 1919, and some estimates believe Ladd completed 97 facial prosthetics single-handedly.

Soon after the signing of the armistice, she returned to the US and received recognition for her actions, from newspaper interviews to “thank you” letters from colleagues.

Patients, too, penned letters to the woman who’d positively altered their lives.

“My gratitude to you will last forever and I will never forget for I wear and will always wear the wonderful fittings which you came up with and it is thanks to you that I can survive being under fire,” wrote Marc Maréchal, a veteran of World War I and patient of Ladd. “It’s thanks to you that I am not buried deep in an old veterans’ hospital.”

In a letter to a friend dated July 8, 1920, Ladd opened with how the decision to halt her work in fine arts to make wartime prosthetics forever altered her perspective.

“I have done better work than ever in my life before,” she wrote. “Absolutely uncompromising sculpture, as I saw it; the search for beauty and austerity of line […] expressing a need of the soul; or its combats; and the love of youth, in all its forms — youth, which has been nearly swept away in the late hellish upheaval.”

In 1932, the French government made Ladd a chevalier of the French Legion of Honor. She continued her work as a sculptor and made beautiful bronze busts and statues. In 1939, Ladd died in Santa Barbara, California, at the age of 60. Her memory lives on through the art she produced and her generous mission to offer peace of mind to the veterans wounded in World War I.

Read Next:

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.