The True Story of Mary Edwards Walker, the Only Female Medal of Honor Recipient

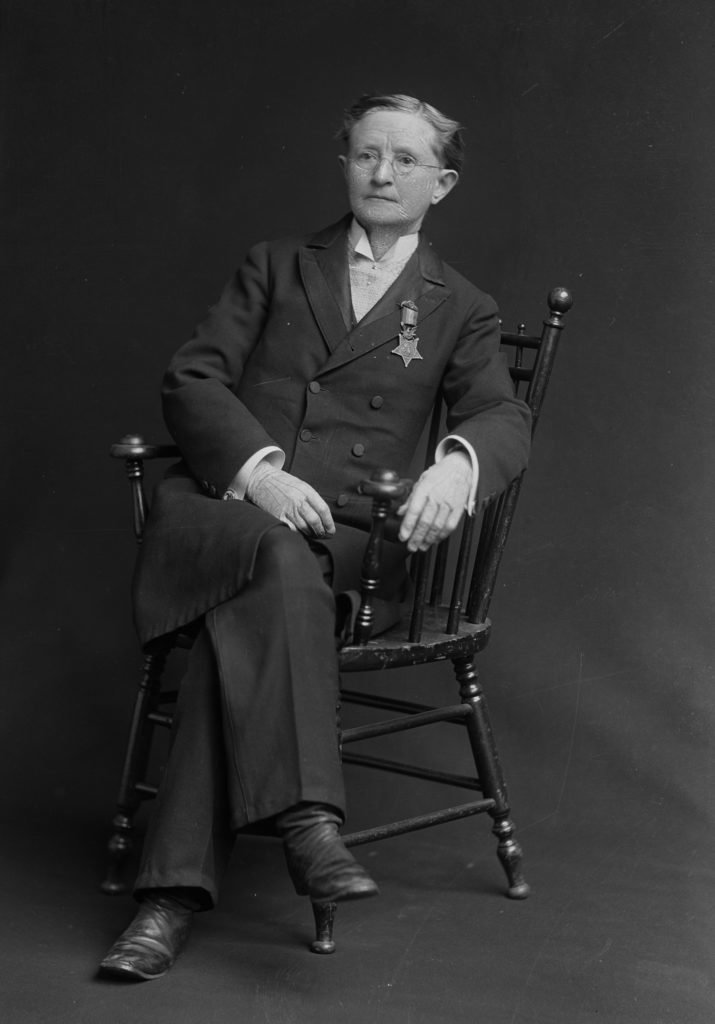

Mary Edwards Walker is the only female Medal of Honor recipient.

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker didn’t have just one title, although her name would suggest otherwise. She was a trailblazer for women’s rights, education equality, fashion, and medicine. She is recognized as the only female Medal of Honor recipient, but there is more to her story than the significance draped around her neck. Walker spoke her mind despite the debate that followed her award. The backlash and societal pressure often silenced other women because women were considered second tier to men during the mid-1800s. Walker was not a misfit, but also not one to cower. Her bravery and mettle were tested through trials few dared to explore.

Avlah and Vesta Walker raised Mary and her five siblings to be free-thinkers on their farm in Oswego, New York. The farm-town’s first public school was built on their land, and Walker gained an early interest in medicine by scrummaging through her father’s old medical books. When Walker was 15 years old, rumblings of an organized women’s movement sent shockwaves through the state. The Seneca Falls Convention was a two-day assembly held on July 19 and 20, 1848, featuring key female leaders who read a “Declaration of Sentiments” that sparked a surge in the women’s suffrage movement.

If there was a woman expected to lead a counterculture trend, Walker was certainly in the conversation to be the forerunner. Working as a schoolteacher in Minetto, New York, Walker saved her money to put herself through medical school. In 1853, she enrolled at Syracuse Medical College (Geneva Medical College at the time), the only medical school in the country that accepted women. Walker, 21 years old at the time, graduated in two years, and she was the only female in her class. She became one of two practicing female physicians, second only to Elizabeth Blackwell, the globe-trotting medical prodigy.

Walker married fellow physician Albert Miller in 1856, but chose to keep her maiden name. The pair started a medical practice together in Rome, New York, but received backlash because men were opposed to receiving treatment from a female physician. Walker ran ads in the Rome Sentinel that read, “Those … who prefer skills to a female physician … have now an excellent opportunity to make their choice.”

In an effort to change public opinion — and because it suited her — Walker often wore trousers, a man’s coat, and other clothing typically worn by men. In a women’s temperance newspaper called Lily, Walker’s friend and colleague Amelia Bloomer challenged one of the editors of the Seneca County Courier, who wrote a piece in 1851 titled “Female Attire” suggesting “a change to Turkish pantaloons and a skirt reaching a little below the knee.” Bloomer had sewn together her own homemade dress and pants, which allowed her to more freely participate in “productive labor” that heavier and larger traditional women’s clothing limited.

“I am the original new woman…Why, before Lucy Stone, Mrs. Bloomer, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony were—before they were, I am.”

Newspapers wrote of her “Bloomer costume,” and cartoonists created derogatory comics. Walker didn’t receive the initial praise from the women’s movement that Bloomer did. However, later in life, she put the debate to bed.

“I am the original new woman…Why, before Lucy Stone, Mrs. Bloomer, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony were—before they were, I am,” she said in 1897. “In the early ’40’s, when they began their work in dress reform, I was already wearing pants…I have made it possible for the bicycle girl to wear the abbreviated skirt, and I have prepared the way for the girl in knickerbockers.”

Walker became one of the first nine elected vice presidents on the National Dress Reform Association Convention and lectured to all who would listen. In the summer of 1860, she filed for divorce from her husband, but it wasn’t finalized until 1869. When the American Civil War began, she went to Washington and attempted to join the Union Army as a medical officer. She was denied at first, but her feisty determination secured her role as an assistant physician. As a volunteer, she had the freedom to take assignments up and down the East Coast without the nagging oversight of the U.S. government.

She aided a severely wounded soldier every step of the way on their journey to his Rhode Island home. She helped create the Women’s Relief Organization, which provided lodging and support to families of soldiers in Washington. In 1862, Walker volunteered again to perform life-saving medical operations as a field surgeon on the outskirts of the Union front lines. A year later, General Ambrose Burnside recommended her for the assistant surgeon position in the 52nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry in Tennessee for the siege of Chattanooga. The director of the medical staff, Dr. Perin, questioned her experience and said having a woman on the team was a “medical monstrosity.”

Fortunately for the men that lay dying on the battlefield and in field hospitals, she was given the position, and they had a seasoned and empathetic surgeon to care for them. Walker later wrote about her experiences during the Battle at Fredericksburg, describing the graphic wartime wounds. “A shell had taken part of his skull away, about as large a piece as a dollar,” she wrote of one soldier’s injury. “I could see the pulsation of the brain, and when he talked, I could see the movement of the same, slight though it was. He was perfectly sensible, and although I never saw him after he was taken to Washington, I learned that he lived several days.”

During a journey to Georgia, Walker was captured by a group of Confederate soldiers. She was on her way to help injured and sick civilians, but some believe she used this as a cover for being a spy. Regardless of its truth, she was imprisoned for espionage, stripped of her Union uniform, had her twin pistols taken away, and was jailed in Richmond, Virginia, as a prisoner of war (POW). She was released after four months and returned to the Ohio 52nd, where she eventually became the first woman to be commissioned as a surgeon in the Army. She served for six months as the chief surgeon for a women’s prison in Louisville, Kentucky, and finished the war at an orphan asylum in Clarksville, Tennessee. Walker received a military pension and, with recommendations from Major Generals William Tecumseh Sherman and George Thomas, she was awarded the Medal of Honor on Nov. 11, 1865.

Walker’s citation highlights her “valuable service to the Government,” how she devoted “herself with much patriotic zeal to the sick and wounded soldiers, both in the field and hospitals, to the detriment of her own health,” and the hardships she endured as a POW. The citation also indicates that “by reason of her not being a commissioned officer in the military service, a brevet or honorary rank cannot, under existing laws, be conferred upon her” so, therefore, “in the opinion of the President an honorable recognition of her services and sufferings should be made.”

The dispute of her inclusion with other combat veterans who received the medal didn’t stop there. The standards for the Medal of Honor were revised in 1917, and Congress reviewed more than 900 awards — Walker’s name was at the top of the list. She was stripped of her “unearned medal,” but since she believed she had earned it, she continued to wear it in public in protest. It was eventually reinstated in 1977 by President Jimmy Carter.

Following the war, Walker toured Great Britain to advocate for women’s issues. She wrote several books, was arrested multiple times for impersonating a man, and continued to be a walking controversy until her death in 1919.

Mary Edwards Walker’s name may not have been collectively celebrated when she was alive, but today she is admired as a pioneer. The U.S. Post Office honored her with a 20-cent stamp in 1982, and she was inducted into the prestigious ranks of the Women’s Hall of Fame in 2000. Though she didn’t live to see much of the progress she worked toward, Walker’s tireless fight for equal rights laid an invaluable foundation for the future.

“Struggle for political rights, for it is through such, and such alone, that you will ever obtain human rights,” she famously wrote in “Hit: Essays on Women’s Rights.” “It is not simply for yourself, but for that great army of young women, who cannot yet see the necessity for anything but smiles and gallantry from the future husbands.”

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.